Chinese musical instruments are traditionally grouped into eight categories (classified by the material from which the instruments were made) known as bā yīn (八音).[1] The eight categories are silk, bamboo, wood, stone, metal, clay, gourd and skin; other instruments considered traditional exist that may not fit these groups. The grouping of instruments in material categories in China is one of the first musical groupings ever devised.

Silk

[edit]Silk (絲) instruments are mostly stringed instruments (including those that are plucked, bowed, and struck). Since ancient times, the Chinese have used twisted silk for strings, though today metal or nylon are more frequently used. Instruments in the silk category include:

Plucked

[edit]- Guqin (Chinese: 古琴; pinyin: gǔqín) – 7-stringed zithers

- Se (Chinese: 瑟; pinyin: sè) – 25-stringed zither with movable bridges (ancient sources say 14, 25 or 50 strings)[citation needed]

- Zheng (古箏) – 16–26 stringed zither with movable bridges

- Konghou (箜篌) – harp

- Huluqin (葫芦琴) – four-stringed lute with gourd body used by the Naxi people of Yunnan

- Huleiqin (忽雷琴) - pear-shaped lute slightly smaller than the pipa, with 2 strings and body covered with snakeskin; it was used during the Tang Dynasty but is no longer used

- Pipa (琵琶) – pear-shaped fretted lute with 4 or 5 strings

- Liuqin (柳琴) – small plucked, fretted lute with a pear-shaped body and four and five strings

- Ruan (Chinese: 阮; pinyin: ruǎn) – moon-shaped lute in five sizes: gaoyin-, xiao-, zhong-, da-, and diyin-; sometimes called ruanqin (阮琴)

- Yueqin (月琴) – plucked lute with a wooden body, a short fretted neck, and four strings tuned in pairs

- Qinqin (秦琴) – plucked lute with a wooden body and fretted neck; also called meihuaqin (梅花琴, literally "plum blossom instrument", from its flower-shaped body)

- Sanxian (三弦) – plucked lute with body covered with snakeskin and long fretless neck; the ancestor of the Japanese shamisen

- Duxianqin (simplified Chinese: 独弦琴; traditional Chinese: 獨弦琴) – the instrument of the Jing people (Vietnamese people in China), a plucked, monochord zither with only one string, tuned to C3.

- Huobosi (火不思) – a plucked long-necked lute of Turkic origin

- Tembor (弹拨尔) – a fretted plucked long-necked lute with five strings in three courses, used in Uyghur traditional music of Xinjiang

- Dutar (都塔尔) – a fretted plucked long-necked lute with two strings, used in Uyghur traditional music of Xinjiang

- Rawap (热瓦普 or 热瓦甫) – a fretless plucked long-necked lute used in Uyghur traditional music of Xinjiang

- Tianqin (天琴) - a 3 strings plucked lute of Zhuang people in Guangxi.

- Qiben (起奔) - a four strings plucked lute of Lisu people

- Wanqin (弯琴: shaped like a dragon boat. Its shape is very similar to Myanmar's saung-gauk. Another variation of the wanqin held in the form of a harp with four strings was found in a painting of Feitian in Mogao caves, Dunhuang province.

- Kongqin (孔琴): A pear-shaped ruan with five strings similar to ukulele

Bowed

[edit]

- Huqin (胡琴) – family of vertical fiddles

- Erhu (二胡) – two-stringed fiddle

- Zhonghu (中胡) – two-stringed fiddle, lower pitch than an erhu

- Gaohu (高胡) – two-stringed fiddle, higher pitch than an erhu; also called yuehu (粤胡)

- Banhu (板胡) – two-stringed fiddle with a coconut resonator and wooden face, used primarily in northern China

- Jinghu (京胡) – two-stringed fiddle (piccolo erhu), very high pitched, used mainly for Beijing opera

- Jing erhu (京二胡) – erhu used in Beijing opera

- Erxian (二弦) – two-stringed fiddle, used in Cantonese, Chaozhou, and nanguan music

- Tiqin (提琴) – two-stringed fiddle, used in kunqu, Chaozhou, Cantonese, Fujian, and Taiwanese music

- Yehu (椰胡) – two-stringed fiddle with coconut body, used primarily in Cantonese and Chaozhou music

- Daguangxian (大广弦) – two-stringed fiddle used in Taiwan and Fujian, primarily by Min Nan and Hakka people; also called datongxian (大筒弦), guangxian (广弦), and daguanxian (大管弦)

- Datong (大筒) – two-stringed fiddle used in the traditional music of Hunan

- Kezaixian (壳仔弦) – two-stringed fiddle with coconut body, used in Taiwan opera

- Liujiaoxian (六角弦) – two-stringed fiddle with hexagonal body, similar to the jing erhu; used primarily in Taiwan

- Tiexianzai (鐵弦仔) – a two-stringed fiddle with metal amplifying horn at the end of its neck, used in Taiwan; also called guchuixian (鼓吹弦)

- Hexian (和弦) – large fiddle used primarily among the Hakka of Taiwan

- Huluhu (simplified Chinese: 葫芦胡; traditional Chinese: 葫盧胡) – two-stringed fiddle with gourd body used by the Zhuang of Guangxi

- Maguhu (simplified Chinese: 马骨胡; traditional Chinese: 馬骨胡; pinyin: mǎgǔhú) – two-stringed fiddle with horse bone body used by the Zhuang and Buyei peoples of southern China

- Tuhu (土胡) – two-stringed fiddle used by the Zhuang people of Guangxi

- Jiaohu (角胡) – two-stringed fiddle used by the Gelao people of Guangxi, as well as the Miao and Dong

- Liuhu (六胡) - six-stringed fiddle of Mongolian people in Inner Mongolia

- Sihu (四胡) – four-stringed fiddle with strings tuned in pairs

- Sanhu (三胡) – 3-stringed erhu with an additional bass string; developed in the 1970s

- Zhuihu (simplified Chinese: 坠胡; traditional Chinese: 墜胡) – two-stringed fiddle with fingerboard

- Zhuiqin (simplified Chinese: 坠琴; traditional Chinese: 墜琴) – two-stringed fiddle with fingerboard

- Leiqin (雷琴) – two-stringed fiddle with fingerboard

- Dihu (低胡) – low pitched two-stringed fiddles in the erhu family, in three sizes:

- Xiaodihu (小低胡) – small dihu, tuned one octave below the erhu

- Zhongdihu (中低胡) – medium dihu, tuned one octave below the zhonghu

- Dadihu (大低胡) – large dihu, tuned two octaves below the erhu

- Dahu (大胡) – another name for the xiaodihu

- Cizhonghu – another name for the xiaodihu

- Gehu (革胡) – four-stringed bass instrument, tuned and played like cello

- Diyingehu (低音革胡) – four-stringed contrabass instrument, tuned and played like double bass

- Laruan (拉阮) – four-stringed bowed instrument modeled on the cello

- Paqin (琶琴) – bowed pear-shaped lute

- Dapaqin (大琶琴) – bass paqin

- Niutuiqin or niubatui (牛腿琴 or 牛巴腿) – two-stringed fiddle used by the Dong people of Guizhou

- Matouqin (馬頭琴) – (Mongolian: morin khuur) – Mongolian two-stringed "horsehead fiddle"

- Xiqin (奚琴) – ancient prototype of huqin family of instruments

- Shaoqin (韶琴) - electric huqin

- Yazheng (simplified Chinese: 轧筝; traditional Chinese: 軋箏) – bowed zither; also called yaqin (simplified Chinese: 轧琴; traditional Chinese: 軋琴)

- Wenzhenqin (文枕琴) – a zither with 9 strings bowed

- Zhengni (琤尼) – bowed zither; used by the Zhuang people of Guangxi

- Ghaychak (艾捷克) – four-stringed bowed instrument used in Uyghur traditional music of Xinjiang; similar to kamancheh[2]

- Sataer (萨塔尔 or 萨它尔) – long-necked bowed lute with 13 strings used in Uyghur traditional music of Xinjiang. 1 playing string and 12 sympathetic strings.

- Khushtar (胡西它尔) – a four-stringed bowed instrument used in Uyghur traditional music of Xinjiang.

Struck

[edit]- Yangqin (揚琴) – hammered dulcimer

- Zhu (筑) – a zither similar to a guzheng, played with a bamboo mallet

- Niujinqin (牛筋琴) – a zither used to accompany traditional narrative singing in Wenzhou, Zhejiang province. Similar to a se but played with a bamboo mallet.

Combined

[edit]- Wenqin (文琴) – a combination of the erhu, konghou, sanxian and guzheng with 50 or more steel strings.

Bamboo

[edit]

Bamboo (竹) mainly refers to woodwind instruments, which includes;

Flutes

[edit]- Dizi (笛子) – transverse bamboo flute with buzzing membrane

- Bangdi (梆笛)

- Xiao (simplified Chinese: 箫; traditional Chinese: 簫; pinyin: xiāo) – end-blown flute; also called dongxiao (simplified Chinese: 洞箫; traditional Chinese: 洞簫)

- Paixiao (simplified Chinese: 排箫; traditional Chinese: 排簫; pinyin: páixiāo) – pan pipes

- Chi (Chinese: 篪; pinyin: chí) – ancient transverse bamboo flute

- Yue (Chinese: 籥; pinyin: yuè) – ancient notched vertical bamboo flute with three finger holes; used in Confucian ritual music and dance

- Xindi (新笛) – modern transverse flute with as many as 21 holes

- Dongdi (侗笛) – wind instrument of the Dong people of southern China

- Koudi (Chinese: 口笛; pinyin: kǒudí) – very small transverse bamboo flute

- Zhuxun (竹埙): a bamboo version of xun

Free reed pipes

[edit]- Bawu (simplified Chinese: 巴乌; traditional Chinese: 巴烏; pinyin: bāwū) – side-blown free reed pipe with finger holes

- Mangtong (Chinese: 芒筒; pinyin: mángtǒng) – end-blown free reed pipe producing a single pitch

- Miaodi (Chinese: 苗族笛; pinyin: miáozú dí)

Single reed pipes

[edit]Double reed pipes

[edit]- Guan (Chinese: 管; pinyin: guǎn) – cylindrical double reed wind instrument made of either hardwood (Northern China) or bamboo (Cantonese); the northern version is also called guanzi (管子) or bili (simplified Chinese: 筚篥; traditional Chinese: 篳篥), the Cantonese version is also called houguan (喉管), and the Taiwanese version is called 鴨母笛, or Taiwan guan (台湾管)

- Shuangguan (雙管) - literally "double guan," an instrument consisting of two guanzi (cylindrical double reed pipes) of equal length, joined together along their length

- Suona (simplified Chinese: 唢呐; traditional Chinese: 嗩吶) – double-reed wind instrument with a flaring metal bell; also called haidi (海笛)

Wood

[edit]

Most wood (木) instruments are of the ancient variety:

- Zhu (Chinese: 柷; pinyin: zhù) – a wooden box that tapers from the top to the bottom, played by hitting a stick on the inside, used to mark the beginning of music in ancient ritual music

- Yu (Chinese: 敔; pinyin: yǔ) – a wooden percussion instrument carved in the shape of a tiger with a serrated back, played by hitting a stick with an end made of approximately 15 stalks of bamboo on its head three times and across the serrated back once to mark the end of the music

- Muyu (simplified Chinese: 木鱼; traditional Chinese: 木魚; pinyin: mùyú) – a rounded woodblock carved in the shape of a fish, struck with a wooden stick; often used in Buddhist chanting

- Paiban (拍板) – a clapper made from several flat pieces of wood; also called bǎn (板), tánbǎn (檀板), mùbǎn (木板), or shūbǎn (书板); when used together with a drum the two instruments are referred to collectively as guban (鼓板)

- Ban

- Zhuban (竹板, a clapper made from two pieces of bamboo)

- Chiban (尺板)

- Bangzi (梆子) – small, high-pitched woodblock; called qiaozi (敲子) or qiaoziban (敲子板) in Taiwan

- Nan bangzi (南梆子)

- Hebei bangzi (河北梆子)

- Zhui bangzi (墜梆子)

- Qin bangzi (秦梆子)

Stone

[edit]The stone (石) category comprises various forms of stone chimes.

- Bianqing (simplified Chinese: 编磬; traditional Chinese: 編磬; pinyin: biānqìng) – a rack of stone tablets that are hung by ropes from a wooden frame and struck using a mallet.

- Tezhong (特鐘) – a single large stone tablet hung by a rope in a wooden frame and struck using a mallet

- Bianzhong (編鐘) – 16 to 65 bronze bells hung on a rack, struck using poles

- Fangxiang (simplified Chinese: 方响; traditional Chinese: 方響; pinyin: fāngxiǎng; Wade–Giles: fang hsiang) – set of tuned metal slabs (metallophone)

- Nao (musical instrument) (鐃) – may refer to either an ancient bell or large cymbals

- Bo (鈸; also called chazi, 镲子) –

- Xiaobo (小鈸, small cymbals)

- Zhongbo (中鈸, medium cymbals; also called naobo (鐃鈸) or zhongcuo

- Shuibo (水鈸, literally "water cymbals")

- Dabo (大鈸, large cymbals)

- Jingbo (京鈸)

- Shenbo (深波) – deep, flat gong used in Chaozhou music; also called gaobian daluo (高边大锣)

- Luo (simplified Chinese: 锣; traditional Chinese: 鑼; pinyin: luó) – gong

- Daluo (大锣) – a large flat gong whose pitch drops when struck with a padded mallet

- Fengluo (风锣) – literally "wind gong," a large flat gong played by rolling or striking with a large padded mallet

- Xiaoluo (小锣) – a small flat gong whose pitch rises when struck with the side of a flat wooden stick

- Yueluo (月锣) – small pitched gong held by a string in the palm of the hand and struck with a small stick; used in Chaozhou music

- Jingluo (镜锣) – a small flat gong used in the traditional music of Fujian [1]

- Pingluo (平锣) – a flat gong[4]

- Kailuluo (开路锣)

- Yunluo (simplified Chinese: 云锣; traditional Chinese: 雲鑼) – literally "cloud gongs"; 10 or more small tuned gongs in a frame

- Shimianluo (十面锣) – 10 small tuned gongs in a frame

- Qing (磬) – a cup-shaped bell used in Buddhist and Daoist ritual music

- Daqing (大磬) – large qing

- Pengling (碰铃; pinyin: pènglíng) – a pair of small bowl-shaped finger cymbals or bells connected by a length of cord, which are struck together

- Dangzi (铛子) – a small, round, flat, tuned gong suspended by being tied with silk string in a round metal frame that is mounted on a thin wooden handlephoto; also called dangdang (铛铛)

- Yinqing (引磬) – an inverted small bell affixed to the end of a thin wooden handlephoto

- Yunzheng (云铮) – a small flat gong used in the traditional music of Fujian [2]

- Chun (錞; pinyin: chún) – ancient bellphoto

- Tonggu (铜鼓) - bronze drum

- Laba (喇叭) – A long, straight, valveless brass trumpet

- Xun (埙, Chinese: 塤; pinyin: xūn) – ocarina made of baked clay

- Fou (Chinese: 缶; pinyin: fǒu) – clay pot played as a percussion instrument

- Taodi (Chinese: 陶笛; pinyin: táo dí)

- Sheng (Chinese: 笙; pinyin: shēng) – free reed mouth organ consisting of varying number of bamboo pipes inserted into a metal (formerly gourd or hardwood) chamber with finger holes

- Baosheng (抱笙) – larger version of the Sheng

- Yu (Chinese: 竽; pinyin: yú) – ancient free reed mouth organ similar to the sheng but generally larger

- Hulusi (simplified Chinese: 葫芦丝; traditional Chinese: 葫蘆絲; pinyin: húlúsī) – free-reed wind instrument with three bamboo pipes which pass through a gourd wind chest; one pipe has finger holes and the other two are drone pipes; used primarily in Yunnan province

- Hulusheng (simplified Chinese: 葫芦笙; traditional Chinese: 葫蘆笙; pinyin: húlúshēng) – free-reed mouth organ with a gourd wind chest; used primarily in Yunnan province

- Fangsheng – Northern China Gourd

- Dagu – (大鼓) – large drum played with two sticks

- Huzuo Dagu (虎座大鼓)

- Huzuo Wujia Gu (虎座鳥架鼓)

- Jian'gu (建鼓)

- Bangu (板鼓) – small, high pitched drum used in Beijing opera; also called danpigu (单皮鼓)

- Biangu (扁鼓) – flat drum, played with sticks

- Paigu (排鼓) – set of three to seven tuned drums played with sticks

- Tanggu (堂鼓) – medium-sized barrel drum played with two sticks; also called tonggu (同鼓) or xiaogu (小鼓)

- Biqigu (荸荠鼓) – a very small drum played with one stick, used in Jiangnan sizhu

- Diangu (点鼓; also called huaigu, 怀鼓) – a double-headed frame drum played with a single wooden beater; used in the Shifangu ensemble music of Jiangsu province and to accompany to kunqu opera

- Huagu (花鼓) – flower drum

- Yaogu (腰鼓) – waist drum

- Taipinggu (太平鼓) – flat drum with a handle; also called dangu (单鼓)

- Zhangu (战鼓 or 戰鼓) – war drum; played with two sticks.

- Bajiaogu (八角鼓) – octagonal tambourine used primarily in narrative singing from northern China.

- Yanggegu (秧歌鼓) – rice planting drum

- Gaogu (鼛鼓) – large ancient drum used to for battlefield commands and large-scale construction

- Bofu (搏拊) – ancient drum used to set tempo

- Jiegu (羯鼓) – hourglass-shaped drum used during the Tang Dynasty

- Tao (鼗; pinyin: táo) or taogu (鼗鼓) – a pellet drum used in ritual music

- Bolang Gu (波浪鼓; pinyin: bo lang gu) – a traditional Chinese pellet drum and toy

- Linggu (铃鼓)

Others

[edit]- Gudi (骨笛) – an ancient flute made of bone[6]

- Hailuo (海螺) – conch shell [3]

- Lilie (唎咧) – reed wind instrument with a conical bore played by the Li people of Hainan

- Lusheng (simplified Chinese: 芦笙; traditional Chinese: 蘆笙; pinyin: lúshēng) – free-reed mouth organ with five or six pipes, played by various ethnic groups in southwest China and neighboring countries

- Kouxian (口弦) – jaw harp, made of bamboo or metal.

- Yedi (叶笛) – tree leaf used as a wind instrument.

- Shuijingdi (水晶笛) - crystal flute.

- Zutongqin (竹筒琴)

Playing contexts

[edit]Chinese instruments are either played solo, collectively in large orchestras (as in the former imperial court) or in smaller ensembles (in teahouses or public gatherings). Normally, there is no conductor in traditional Chinese music, nor any use of musical scores or tablature in performance. Music was generally learned aurally and memorized by the musician(s) beforehand, then played without aid. As of the 20th century, musical scores have become more common, as has the use of conductors in larger orchestral-type ensembles.

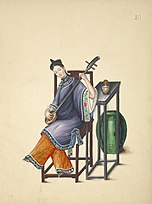

Musical instruments in use in the 1800s

[edit]These watercolour illustrations, made in China in the 1800s, show several types of musical instruments being played:

-

Woman playing a dizi.

-

Woman playing a jinghu.

-

Woman playing a luo.

-

Woman playing a pipa.

-

Woman playing a sanxian.

-

Woman playing a yunluo.

-

Woman playing a xiaoluo.

-

Woman playing a haotou.

-

Woman playing a xiao.

-

Woman playing what looks like a yangqin or some sort of psaltery-like instrument.

See also

[edit]- Music of China

- Chinese culture

- Chinese art

- Chinese instrument classification

- List of ensemble formations in traditional Chinese music

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Don Michael Randel, ed. (2003). The Harvard Dictionary of Music (4th ed.). Harvard University Press. pp. 260–262. ISBN 978-0674011632.

- ^ "Archived copy". www.chinamedley.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2006. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Patricia Ebrey (1999), Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 148.

- ^ "photo". Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Chinese Musical Instrument-Bolanggu

- ^ Endymion Wilkinson (2000), Chinese history, ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4

- Sources

- Lee, Yuan-Yuan and Shen, Sinyan. Chinese Musical Instruments (Chinese Music Monograph Series). 1999. Chinese Music Society of North America Press. ISBN 1-880464-03-9

- Shen, Sinyan. Chinese Music in the 20th Century (Chinese Music Monograph Series). 2001. Chinese Music Society of North America Press. ISBN 1-880464-04-7

- Yuan, Bingchang, and Jizeng Mao (1986). Zhongguo Shao Shu Min Zu Yue Qi Zhi. Beijing: Xin Shi Jie Chu Ban She/Xin Hua Shu Dian Beijing Fa Xing Suo Fa Xing. ISBN 7-80005-017-3.

External links

[edit]- Chinese musical instruments

- Chinese Musical Instruments Leisure and Cultural Services Department, Hong Kong

- Chime A look at ancient Chinese instruments

- Chinese musical instruments (Chinese)

- Chinese Instruments Website (English)

- Chinese musical instruments

- The Musical Instruments E-book

- World of Instrumental Music

- The Grand Chinese New Year Concert

- Chinese Instrument

- Chinese Musical Instruments (The Modern Appearance)

- https://www.britannica.com/art/qin-musical-instrument