Lyocell is a semi-synthetic fiber used to make textiles for clothing and other purposes.[1] It is a form of regenerated cellulose made by dissolving pulp and dry jet-wet spinning. Unlike rayon made by the more common viscose processes, Lyocell production does not use carbon disulfide,[2][3] which is toxic to workers and the environment.[4][5][2] Lyocell was originally trademarked as Tencel in 1982.

"Lyocell" has become a genericized trademark, used to refer to the Lyocell process for making cellulose fibers.[3][6] The U.S. Federal Trade Commission defines Lyocell as "a fiber composed of cellulose precipitated from an organic solution in which no substitution of the hydroxy groups takes place, and no chemical intermediates are formed". It classifies the fiber as a sub-category of rayon.[7]

Names

[edit]Other trademarked names for Lyocell fibers are Tencel (Lenzing AG),[8] Newcell (Akzo Nobel), and Seacell (Zimmer AG).[9] The Aditya Birla Group also sells it under the brand name Excel.[10] There are other manufacturers like Sateri which sell their product under generic name Lyocell[11]

History

[edit]The development of Tencel was motivated by environmental concerns; researchers sought to manufacture rayon by means less harmful than the viscose method.[12]

The Lyocell process was developed in 1972 by a team at the now defunct American Enka fibers facility at Enka, North Carolina. In 2003, the American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists (AATCC) awarded Neal E. Franks their Henry E. Millson Award for Invention for Lyocell.[13] In 1966–1968, D. L. Johnson of Eastman Kodak Inc. studied NMMO solutions. From 1969 to 1979, American Enka tried unsuccessfully to commercialize the process.[12] The operating name for the fiber inside the Enka organization was "Newcell", and the development was carried through a pilot plant scale before the work was stopped.

The basic process of dissolving cellulose in NMMO was first described in a 1981 patent by Mcorsley for Akzona Incorporated[12][14] (the holding company of Akzo). In the 1980s the patent was licensed by Akzo to Courtaulds and Lenzing.[6]

The fiber was developed by Courtaulds Fibres under the brand name "Tencel" in the 1980s. In 1982, a 100-kg/week pilot plant was built in Coventry, UK, and production increased tenfold (to a ton/week) in 1984. In 1988, a 25-ton/week semi-commercial production line opened at the Grimsby, UK, pilot plant.[15][12]

The process was first[16] commercialized at Courtaulds' rayon factories at Mobile, Alabama[17] (1990[16]), and at the Grimsby plant (1998).[16] In January 1993, the Mobile Tencel plant reached full production levels of 20,000 tons per year, by which time Courtaulds had spent £100 million and 10 years on Tencel development. Tencel revenues for 1993 were estimated as likely to be £50 million. The second plant in Mobile was planned.[17] By 2004, production had quadrupled to 80,000 tons.[6]

Lenzing began a pilot plant in 1990,[12] and commercial production in 1997, with 12 metric tonnes/year made in a plant in Heiligenkreuz im Lafnitztal, Austria.[12][6][18] When an explosion hit the plant in 2003 it was producing 20,000 tonnes/year, and planning to double capacity by the end of the year.[19] In 2004 Lenzing was producing 40,000 tons [sic, probably metric tonnes].[6] In 1998, Lenzing and Courtaulds reached a patent dispute settlement.[6]

In 1998 Courtaulds was acquired by competitor Akzo Nobel,[20] who combined the Tencel division with other fiber divisions under the Accordis banner, then sold them to private equity firm CVC Partners. In 2000, CVC sold the Tencel division to Lenzing AG, who combined it with their "Lenzing Lyocell" business, but maintained the brand name Tencel.[6] They took over the plants in Mobile and Grimsby, and by 2015 was the largest Lyocell producer at 130,000 tonnes/year.[12]

Uses

[edit]

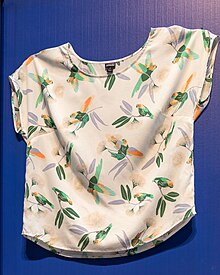

It is used in many everyday fabrics. Staple fibers are used in clothes such as denim, chino, underwear, casual wear, and towels. Filament fibers, which are generally longer and smoother than staple fibers,[21] are used in items that have a silkier appearance such as women's clothing and men's dress shirts. Lyocell may be blended with a variety of other fibers such as silk, cotton, rayon, polyester, linen, nylon, and wool. When mixed with other fibers, the resulting fabric is much stronger and more resistant to wear, tear, and pilling.[22] Lyocell also is used in conveyor belts, specialty papers, and medical dressings.[23]

Properties

[edit]

Lyocell shares many properties with other fibers such as cotton, linen, silk, ramie, hemp, and viscose rayon (to which it is very closely related chemically). Lyocell is 50% more absorbent than cotton, [24] and has a longer wicking distance compared to modal fabrics of a similar weave. [25]

Compared to cotton, consumers often say Lyocell fibers feel softer and "airier," due to their better ability to wick moisture. Industry claims of higher resistance to wrinkling are as yet unsupported. Lyocell fabric may be machine washed or dry cleaned. It drapes well and may be dyed many colors, needing slightly less dye than cotton to achieve the same depth of color. [26][10]

Manufacturing process

[edit]The Lyocell process uses a direct solvent rather than indirect dissolution such as the xanthation-regeneration route in the viscose process. Lyocell fiber is produced from dissolving pulp, which contains cellulose in high purity with little hemicellulose and no lignin. Hardwood logs (such as oak and birch[better source needed][27]) are chipped into squares about the size of postage stamps. The chips are digested chemically, either with the prehydrolysis-kraft process or with sulfite process, to remove the lignin and hemicellulose. The pulp is bleached to remove the remaining traces of lignin, dried into a continuous sheet and rolled onto spools. The pulp has the consistency of thick posterboard paper and is delivered in rolls weighing some 500 lb (230 kg).

N-Methylmorpholine N-oxide is a key solvent in the Lyocell process

At the Lyocell mill, rolls of pulp are broken into one-inch squares and dissolved in N-methylmorpholine N-oxide (NMMO[2]), giving a solution called "dope". The filtered cellulose solution is then pumped through spinnerets, devices used with a variety of synthetic fibers. The spinneret is pierced with small holes rather like a shower head; when the solution is forced through it, continuous strands of filament come out. The fibers are drawn in air to align the cellulose molecules, giving the Lyocell fibers its characteristic high strength. The fibers are then immersed into a water bath, where desolvation of the cellulose sets the fiber strands. The bath contains some dilute amine oxide in a steady state concentration. Then the fibers are washed with demineralised water. Next, the Lyocell fiber passes to a drying area, where the water is evaporated from it.

Manufacture then follows the same route as with other kinds of fibers such as viscose. The strands pass to a finishing area, where a lubricant, which may be a soap or silicone or other agents, depending on the future use of the fiber, is applied. This step is a detangler, prior to carding and spinning into yarn. At this stage, the dried, finished fibers are in a form called tow, a large, untwisted bundle of continuous lengths of filament. The bundles of tow are taken to a crimper, a machine that compresses the fiber, giving it texture and bulk. The crimped fiber is then carded by mechanical carders, which perform a combing action to separate and order the strands. The carded strands are then cut and baled for shipment to a fabric mill. The entire manufacturing process, from unrolling the raw cellulose to baling the fiber, takes roughly two hours. After this, the Lyocell may be processed in many ways. It may be spun with another fiber, such as cotton or wool. The resulting yarn can be woven or knitted like any other fabric, and may be given a variety of finishes, from soft and suede-like to silky.[23]

The amine oxide used to dissolve the cellulose and set the fiber after spinning (NMMO) is recycled. Typically,[27] 99 percent of the amine oxide is recovered.[10] NMMO biodegrades without producing harmful products.[2] Since there is little waste product, this process is relatively eco-friendly, though it is energy-intensive.[10]

Future research

[edit]Lyocell's lack of antibacterial properties is limiting its uses in the medical field. Due to its biodegradability, low toxicity, and comfort, Lyocell would become a useful material for antibacterial garments. Several approaches have been tested to introduce antibacterial capabilities. Three general approaches have been studied to achieve this: physical blending, chemical reaction, and post-treatment. Physical blending methods introduce antibacterial agents into the spinning dope. In chemical reaction methods, antibacterial additives are crosslinked into the Lyocell fibers and therefore giving antimicrobial properties. In post-treatment methods, antibacterial additives are being deposited on Lyocell fiber surfaces through physical coating, padding, or impregnation processes. Physical blending and post-treatment methods appear to be the most promising for large-scale manufacturing. Careful consideration of cost, preparation time, and antibacterial effectiveness is required to select the best method. Creating successful modification of Lyocell fibers to enhance antibacterial properties would allow to manufacture products for health care (such as lab coats, caps, gowns), hygiene products (scrubs, sanitary napkins), and clothing (socks, underwear).[28]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Krässig, Hans; Schurz, Josef; Steadman, Robert G.; Schliefer, Karl; Albrecht, Wilhelm; Mohring, Marc; Schlosser, Harald (2002). "Cellulose". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a05_375.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ a b c d "Regenerated cellulose by the Lyocell process, a brief review of the process and properties :: BioResources". BioRes. 2018.

- ^ a b Tierney, John William (2005). Kinetics of Cellulose Dissolution in N-MethylMorpholine-N-Oxide and Evaporative Processes of Similar Solutions (Thesis).

- ^ Swan, Norman; Blanc, Paul (20 February 2017). "The health burden of viscose rayon". ABC Radio National.

- ^ Michelle Nijhuis. "Bamboo Boom: Is This Material for You?". Scientific American. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanearth0609-60.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Lenzing Acquires TENCEL®, 2004". Archived from the original on 2010-03-23. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- ^ "16 CFR 303.7(d)". ecfr.gov.

- ^ "What is TENCEL™ fibers fabric made of? About TENCEL™ Lyocell & Modal fibers".

- ^ B. Ozipek, H. Karakas, in Advances in Filament Yarn Spinning of Textiles and Polymers, 2014. As quoted by Elsevier

- ^ a b c d "Material Guide: How Ethical is Tencel?". Good On You. 2018-07-27. Retrieved 2020-07-21.

- ^ "[:en]Lyocell Fibre[:zh]莱赛尔[:]".

- ^ a b c d e f g Johnathan Y. Chen. Textiles and fashion: materials, design and technology, 2015. As quoted by Elsevier

- ^ "Millson Award for Invention". AATCC.

- ^ US 4246221, Mcorsley, C., "Process for Shaped Cellulose Article Prepared from Solution Containing Cellulose Dissolved in a Tertiary Amine N-oxide Solvent", published 1981 New York, New York, Akzona Incorporated.

- ^ "Introducing Tencel lyocell".

- ^ a b c "Lyocell Fiber - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- ^ a b Ipsen, Erik (25 February 1993). "INTERNATIONAL MANAGER: Freed of Textile Business, Courtaulds Is Doing Fine". International Herald Tribune.

- ^ "Lenzing Group". www.lenzing.com. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- ^ Beacham, Will. "Explosion and fire halts 'Lyocell' output at Lenzing's Heiligenkreuz, Austria plant". ICIS Explore.

- ^ "Bulletin EU 6-1998 (en): 1.3.50 | Akzo Nobel/Courtaulds". Europa. Archived from the original on 22 September 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^ Yates, Marypaul (2002). Fabrics: a guide for interior designers and architects (1st ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-73062-3.

- ^ Sewport Support Team. (n.d.). What is Lyocell Fabric: Properties, how its made and where. Sewport. https://sewport.com/fabrics-directory/lyocell-fabric#:~:text=Lyocell%20is%20a%20semi%2Dsynthetic,of%20cellulose%20derived%20from%20wood.

- ^ a b Kadolph, Sara; Langford, Anna (2002). Textiles (Ninth ed.). Prentice Hall.

- ^ "Pulp fabric: Everything you need to know about lyocell". TheGuardian.com. 18 November 2019.

- ^ Ozdemir, Hakan (2017-03-01). "Permeability and Wicking Properties of Modal and Lyocell Woven Fabrics Used for Clothing". Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics. 12 (1). doi:10.1177/155892501701200102. ISSN 1558-9250.

- ^ "FiberSource".

- ^ a b "How lyocell is made - material, manufacture, making, used, processing, steps, industry, machine". www.madehow.com. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- ^ Edgar, Kevin J.; Zhang, Huihui (15 December 2020). "Antibacterial modification of Lyocell fiber: A review". Carbohydrate Polymers. 250: 116932. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116932. PMID 33049845. S2CID 222352836. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

External links

[edit]- Blanc, Paul David (2016). Fake silk : the lethal history of viscose rayon. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 328. ISBN 9780300204667.

- Dissolving of Cellulosics

- Federal Trade Commission webpage on textiles

- Information about the fiber from fibersource.com

- OSU fact sheet

- Tencel at Courtaulds: From Genesis to Exodus and Beyond… – By Calvin Woodings

- Uniform Reuse have a long pdf report on fabric properties and suppliers including lyocell

- Lyocell Comparison