The term monumental sculpture is often used in art history and criticism, but not always consistently. It combines two concepts, one of function, and one of size, and may include an element of a third more subjective concept. It is often used for all sculptures that are large. Human figures that are perhaps half life-size or above would usually be considered monumental in this sense by art historians,[1] although in contemporary art a rather larger overall scale is implied. Monumental sculpture is therefore distinguished from small portable figurines, small metal or ivory reliefs, diptychs and the like.

The term is also used to describe sculpture that is architectural in function, especially if used to create or form part of a monument of some sort, and therefore capitals and reliefs attached to buildings will be included, even if small in size. Typical functions of monuments are as grave markers, tomb monuments or memorials, and expressions of the power of a ruler or community, to which churches and so religious statues are added by convention, although in some contexts monumental sculpture may specifically mean just funerary sculpture for church monuments.

The third concept that may be involved when the term is used is not specific to sculpture, as the other two essentially are. The entry for "Monumental" in A Dictionary of Art and Artists by Peter and Linda Murray describes it as:[2]

The most overworked word in current art history and criticism. It is intended to convey the idea that a particular work of art, or part of such a work, is grand, noble, elevated in idea, simple in conception and execution, without any excess of virtuousity, and having something of the enduring, stable, and timeless nature of great architecture. ... It is not a synonym for 'large'.

However, this does not constitute an accurate or adequate description of the use of the term for sculpture, though many uses of the term that essentially mean either large or "used in a memorial" may involve this concept also, in ways that are hard to separate. For example, when Meyer Schapiro, after a chapter analysing the carved capitals at Moissac, says: "in the tympanum of the south portal [(right)] the sculpture of Moissac becomes truly monumental. It is placed above the level of the eye, and is so large as to dominate the entire entrance. It is a gigantic semi-circular relief ...",[3] size is certainly the dominant part of what he means by the word, and Schapiro's further comments suggest that a lack of "excess of virtuousity" does not form part of what he intends to convey. Nonetheless, parts of the Murray's concept ("grand, noble, elevated in idea") are included in his meaning, although "simple in conception and execution" hardly seems to apply.

Meaning in different contexts

[edit]It is only in wealthy societies that the possibility of creating sculptures that are large but merely decorative really exists (at least in long-lived materials such as stone), so for most of art history the different senses of the term cause no difficulties.[4] The term may be used differently for different periods, with breaks occurring around the Renaissance and the early 20th century: for ancient and medieval sculpture size is normally the criterion, though smaller architectural sculptures are usually covered by the term, but in the Early Modern period a specific funerary function may be meant, before the typical meaning once again comes to refer to size alone for contemporary sculpture.[5] The relevant chapters in Parts 2-4 of The Oxford History of Western Art are titled as follows: "Monumental Sculpture to c.1300", "Monumental Sculpture 1300–1600", "Free-standing Sculpture c.1600–c.1700", "Forms in Space c.1700–1770", "Sculptures and Publics" (1770–1914).[6]

In art history

[edit]Appearance of monumental sculpture in a culture

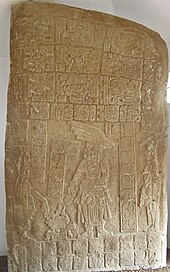

[edit]In archeology and art history the appearance, and sometimes disappearance, of monumental sculpture (using the size criterion) in a culture, is regarded as of great significance, though tracing the emergence is often complicated by the presumed existence of sculpture in wood and other perishable materials of which no record remains;[7] the totem pole is an example of a tradition of monumental sculpture in wood that would leave no traces for archaeology. The ability to summon the resources to create monumental sculpture, by transporting usually very heavy materials and arranging for the payment of what are usually regarded as full-time sculptors, is considered a mark of a relatively advanced culture in terms of social organization.

In Ancient Egypt, the Great Sphinx of Giza probably dates to the 3rd millennium BC, and may be older than the Pyramids of Egypt. The discovery in 1986 of an ancient Chinese Bronze Age 8.5 foot tall bronze statue at Sanxingdui disturbed many ideas held about early Chinese civilization, since only much smaller bronzes were previously known.[8] Some undoubtedly advanced cultures, such as the Indus Valley civilization, appear to have had no monumental sculpture at all, though producing very sophisticated figurines and seals. The Mississippian culture seems to have progressing towards its use, with small stone figures, when it collapsed. Other cultures, such as Ancient Egypt and the Easter Island culture, seem to have devoted enormous resources to very large-scale monumental sculpture from a very early stage.

Disappearance of monumental sculpture

[edit]When a culture ceases to produce monumental sculpture, there may be a number of reasons. The most common is societal collapse, as in Europe during the so-called Dark Ages or the Classic Maya collapse in Mesoamerica. Another may be aniconism, usually religiously motivated, as followed the Muslim conquests. Both the rise of Christianity (initially) and later the Protestant Reformation brought a halt to religious monumental sculpture in the regions concerned, and greatly reduced production of any monumental sculpture for several centuries. Byzantine art, which had largely avoided the societal collapse in the Western Roman Empire, never resumed the use of monumental figurative sculpture, whether in religious or secular contexts, and was to ban even two-dimensional religious art for a period in the Byzantine iconoclasm.

Contemporary work

[edit]"Monumental sculpture" is still used within the stoneworking and funeral trades to cover all forms of grave headstones and other funerary art, regardless of size. In contemporary art, however, the term is used to refer to all large sculptures regardless of purpose, and also carries a sense of permanent, solid, objects, rather than the temporary or fragile assemblages used in much contemporary sculpture.[9] Sculptures covered by the term in modern art are likely to be over two metres in at least one dimension, and sufficiently large not to need a high plinth, though they may have one. Many are still commissioned as public art, often for placing at outdoor sites.

Gallery

[edit]-

Soviet memorial for Salaspils camp in Latvia by Ļevs Bukovskis (1967)

-

Płomienne ptaki (Fire Birds) (1977) by Władysław Hasior in Koszalin, Poland

-

Elogio del Horizonte (Eulogy to the Horizon), concrete (1989), a contemporary monumental sculpture, by Eduardo Chillida, at Gijon, Spain

-

Laura Facey's Redemption Song (2003). Jamaica's national monument to the Emancipation from Slavery

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ For example, none of the figures in sculptures at the Santo Domingo de Silos Abbey are larger than this, and they are described by Meyer Schapiro as "one of the largest groups of monumental carving in Spanish Romanesque art". Schapiro, 29

- ^ Peter and Linda Murray (1968). "Monumental". A Dictionary of Art and Artists (Revised ed.). Penguin.

- ^ Schapiro, 201

- ^ The Getty Art & Architecture Thesaurus Online definition only refers to "Very large, comparable to a typical monument in massiveness", but the notes below on the many reference works consulted give a range of different emphases on size and function.

- ^ For examples, concerned with funerary sculpture only are: The Silent Rhetoric of the Body A History of Monumental Sculpture and Commemorative Art in England, 1720–1770, by Matthew Craske, Yale UP, ISBN 0-300-13541-6, ISBN 978-0-300-13541-1 [1], and several of the titles covered on the bibliography page of the website of the Church Monuments Society. For contemporary sculpture, see The New York Times of August 30, 1981, "Arts role in government architecture is explore" by Helen Harrison. All accessed April 29, 2009

- ^ OUP Catalogue

- ^ See for example Martin Robertson, A shorter history of Greek art, p. 9, Cambridge University Press, 1981, ISBN 0-521-28084-2, ISBN 978-0-521-28084-6 Google books

- ^ NGA, Washington

- ^ See for example, several uses of the term in "Monumentally Virtual, Ephemerally Physical: Directions in new sculpture and new media", blogpost by Joseph Taylor McRae, Lecturer in Computer Games Arts and editor of Art/Games Journal, published on May 25th, 2016, by the Cass Sculpture Foundation

References

[edit]- Schapiro, Meyer, Selected Papers, volume 2, Romanesque Art, 1977, Chatto & Windus, London, ISBN 0-7011-2239-0

- Contemporary monumental sculptures