| Part of a series on |

| Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) |

|---|

|

| Islamic studies |

Murabaḥah, murabaḥa, or murâbaḥah (Arabic: مرابحة, derived from ribh Arabic: ربح, meaning profit) was originally a term of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) for a sales contract where the buyer and seller agree on the markup (profit) or "cost-plus" price[1] for the item(s) being sold.[2] In recent decades it has become a term for a very common form of Islamic (i.e., "shariah compliant") financing, where the price is marked up in exchange for allowing the buyer to pay over time—for example with monthly payments (a contract with deferred payment being known as bai-muajjal). Murabaha financing is basically the same as a rent-to-own arrangement in the non-Muslim world, with the intermediary (e.g., the lending bank) retaining ownership of the item being sold until the loan is paid in full.[3] There are also Islamic investment funds and sukuk (Islamic bonds) that use murabahah contracts.[4]

The purpose of murabaha is to finance a purchase without involving interest payments, which most Muslims (particularly most scholars) consider riba (usury) and thus haram (forbidden).[5] Murabaha has come to be "the most prevalent"[5] or "default" type of Islamic finance.[6]

A proper murâbaḥah transaction differs from conventional interest-charging loans in several ways. The buyer/borrower pays the seller/lender at an agreed-upon higher price; instead of interest charges, the seller/lender makes a religiously permissible "profit on the sale of goods".[5][7] The seller/financer must take actual possession of the good before selling it to the customer, and must assume "any liability from delivering defective goods".[8] Sources differ as to whether the seller is permitted to charge extra when payments are late,[9] with some authors stating any late fees ought to be donated to charity,[10][11][12] or not collected unless the buyer has "deliberately refused" to make a payment.[8] For the rate of markup, murabaha contracts "may openly use" riba interest rates such as LIBOR "as a benchmark", a practice approved of by the scholar Taqi Usmani.[13][Note 1]

Conservative scholars promoting Islamic finance consider murabaha to be a "transitory step" towards a "true profit-and-loss-sharing mode of financing",[16] and a "weak"[17] or "permissible but undesirable"[18] form of finance to be used where profit-and-loss-sharing is "not practicable."[16][19] Critics/skeptics complain/note that in practice most "murabaḥah" transactions are merely cash-flows between banks, brokers, and borrowers, with no buying or selling of commodities;[20] that the profit or markup is based on the prevailing interest rate used in haram lending by the non-Muslim world;[21] that "the financial outlook" of Islamic murabaha financing and conventional debt/loan financing is "the same",[22] as is most everything else besides the terminology used.[23]

Religious justification

[edit]While orthodox Islamic scholars have expressed a lack of enthusiasm for murabaha transactions,[24] calling them "no more than a second best solution" (Council of Islamic Ideology)[24] or a "borderline transaction" (Islamic scholar Taqi Usmani),[25] nonetheless they are defended as Islamically permitted.

According to Taqi Usmani, the reference to permitted "trade" or "trafficking" in Quran aya 2:275:[26]

"... they say, 'Trafficking (trade) is like usury,' [but] God has permitted trafficking, and forbidden usury .."

refers to credit sales such as murabaha, the "forbidden usury" refers to charging extra for late payment (late fees), and the "they" refers to non-Muslims who didn't understand why if one was allowed both were not:[27]

the objection of the infidels ... was that when they increase the price at the initial stage of sale, it has not been held as prohibited but when the purchaser fails to pay on the due date, and they claim an additional amount for giving him more time, it is termed as "riba" and haram. The Holy Qur'an answered this objection by saying: "Allah has allowed sale and forbidden riba."[28]

Usmani states that while it may appear to some people that allowing a buyer more time to pay for some product/commodity (deferred payment) in exchange for their paying a higher price is effectively the same as paying interest on a loan,[29] this is incorrect. In fact, just as a buyer may pay more for a product/commodity when the seller has a cleaner shop or more courteous staff, so too the buyer may pay more when given more time to complete payment for that product or commodity.[29] When this happens, the extra they pay is not riba but just "an ancillary factor to determining the price". In such a case, according to Usmani, the "price is against a commodity and not against money" — and so permitted in Islam.[30] When a credit transaction is made without the purchase of a specific commodity or product, (i.e. a loan is made charging interest), the added charge for deferred payment is for "nothing but time", and so is forbidden riba.[30] However according to another Islamic finance promoter—Faleel Jamaldeen -- "murabaha payments represent debt" and because of that are not "negotiable or tradable" as Islamic finance instruments, making them (according to Jamaldeen) unpopular among investors.[31]

Hadith also supports use of credit-sales transactions such as murabaḥa. Another scholar, M.O.Farooq, states "it is well-known and supported by many hadiths that the Prophet had entered into credit-purchase transactions (nasi'ah) and also that he paid more than the original amount" in his repayment.[32][Note 2][Note 3]

Usmani states that "this position" is accepted "unanimously" by the "four [ Sunni ] schools" of Islamic law and "the majority" of the Muslim jurists.[25] Murabahah and related fixed financing has been approved by a number of government reports in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan on how to eliminate Interest. [Note 4]

- Late payment

Usmani presents a theory of why sellers are allowed to charge for providing credit to the lender/buyer, but are guilty of riba when charging for late payment. In a true (non-riba) murâbaḥah transaction (Usmani states) "the whole price ... is against a commodity and not against money" and so "... once the price is fixed, it relates to the commodity, and not to the time". Consequently "the price will remain the same and can never be increased by the seller." If the price had "been against time", (which is forbidden) "it might have been increased, if the seller allows ... more time" for repayment when the bill is past due.[34]

(Usmani and other Islamic finance scholars[8][35] agree that not being able to penalize a lender/buyer for late payment has led to late payments in murâbaḥah and other Islamic finance transactions. Usmani states that a "problem" of murabahah financing is that "if the client defaults in payment of the price at the due date, the price cannot be increased".[36] According to one source (Mushtak Parker), Islamic financial institutions "have long tried to grapple with the issue of delayed payments or defaults, but thus far there is no universal consensus across jurisdictions in this respect."[35])

Islamic finance, use, variations

[edit]- Limits of use in fiqh

In its 1980 Report on the Elimination of Interest from the Economy,[37] the Council of Islamic Ideology of Pakistan stated that murabahah should

- be undertaken only when the borrower wants to borrow to purchase a some item

- must involve

- the item then being sold to the customer through a valid sale;[38]

- be used to the "minimum extent" and

- only in cases where profit and loss sharing is not practicable.[38]

Murâbaḥah is one of three types of bayu-al-amanah (fiduciary sale), requiring an "honest declaration of cost". (The other two types are tawliyah—sale at cost—and wadiah—sale at specified loss.)

According to Taqi Usmani "in exceptional cases" an Islamic bank or financial institution may lend cash to the customer for a murâbaḥah, but this is when the customer is acting as an agent of the bank in buying the good the customer needs financed.

[W]here direct purchase from the supplier is not practicable for some reason, it is also allowed that he makes the customer himself his agent to buy the commodity on his behalf. In this case the client first purchases the commodity on behalf of his financier and takes its possession as such. Thereafter, he purchases the commodity from the financier for a deferred price.[39]

The idea that the seller may not use murâbaḥah if profit-sharing modes of financing such as mudarabah or musharakah are practicable, is supported by other scholars that those in the Council of Islamic Ideology.[16][19]

- Limits of use in practice

But these involve risks of loss, profit-sharing modes of financing cannot guarantee banks income. Murabahah, with its fixed margin, offers the seller (i.e. the bank/financier) a more predictable income stream. One estimate is that 80% of Islamic lending is by murabahah.[40] M. Kabir Hassan reports that murabaha accounts are quite profitable. As of 2005, "the average cost efficiency" for murabaha was "74%, whereas average profit efficiency" even higher at 84%. Hassan states, "although Islamic banks are less efficient in containing cost, they are generally efficient in generating profit."[41]

Islamic banker and author Harris Irfan writes that use of murabaha "has become so distorted from its original intent that it has become the single most common method of funding inter-bank liquidity and corporate loans in the Islamic finance industry."[42] A number of economists have noted the dominance of murabahah in Islamic finance, despite its theological inferiority to profit and loss sharing.[43][44][45] One scholar has coined the term "the murabaha syndrome" to describe this.[46]

The accounting treatment of murâbaḥah, and its disclosure and presentation in financial statements, vary from bank to bank. If the exact cost of the item(s) cannot be or are not ascertained, they are sold on the basis of musawamah (bargaining).[5] Different banks use this instrument in varying ratios. Typically, banks use murabaha in asset financing, property, microfinance and commodity import-export.[47] The International Monetary Fund reports that, Murâbaḥah transactions are "widely used to finance international trade, as well as for interbank financing and liquidity management through a multistep transaction known as tawarruq, often using commodities traded on the London Metal Exchange" (LME).[8]

The basic murabaha transaction is a cost-plus-profit purchase where the item the bank purchases is something the customer wants but does not have cash at the time to buy directly.[48] However, there are other murabaha transactions where the customer wants/needs cash and the product/commodity the bank buys is a means to an end. (Thus violating the requirement spelled out by Usmani and others.)

Variations

[edit]In addition to being used by Islamic banks, murabahah contracts have been used by Islamic investment funds (such as SHUAA Capital of Saudi Arabia and Al Bilad Investment Company),[4] and sukuk (also called Islamic bonds)(an example being a 2005 sukuk issued by Arcapita Bank sukuk in 2005).[4]

Bay' bithaman 'ajil

[edit](Also called Bai' muajjal[49] abbreviated BBA, and known as credit sale or deferred payment sale). Reportedly the most popular mode of Islamic financing is cost-plus murabaha in a credit sale setting (Bay bithaman 'ajil) with "an added binding promise on the customer to purchase the property, thus replicating secured lending in `Shari'a compliant` manner." The concept was developed by Sami Humud, and shortly after it became popular Islamic Banking began its strong growth in the late 1970s.[50]

Another source (Skrine law firm) distinguishes between Murabahah and Bay' bithaman 'ajil (BBA) banking products, saying that in BBA disclosure of the cost price of the item being financed is not a condition of the contract.[51]

One variation on murabahah (known as "Murabahah to the Purchase Orderer" according to Muhammad Tayyab Raza) allows the customer to serve as the "agent" of the bank, so that the customer buys the product using the bank's borrowed funds.[39] The customer then repays the bank similar to a cash loan. While this is not "preferable" from a Sharia point of view, it avoids extra cost and the problem of a financial institution lacking the expertise to identify the exact or best product or the ability to negotiate a good price.[52]

Bay' al-Ina

[edit](Also Bay' al-'Inah). This simple form of murabahah involves the Islamic bank buying some object from the customer (such as their house or motor vehicle) for cash, then selling the object back to the customer at a higher price, with payment to be deferred over time. The customer now has cash and will be paying the bank back a larger sum of money over time. This resemblance to a conventional loan has led to bay' al-ina being criticized as a ruse for a cash loan repaid with interest.[53] It was used by a number of modern Islamic financial institutions despite condemnation by jurists, but in recent years its use is "very much limited" according to Harris Irfan.[54]

Bay' al-Tawarruq

[edit]

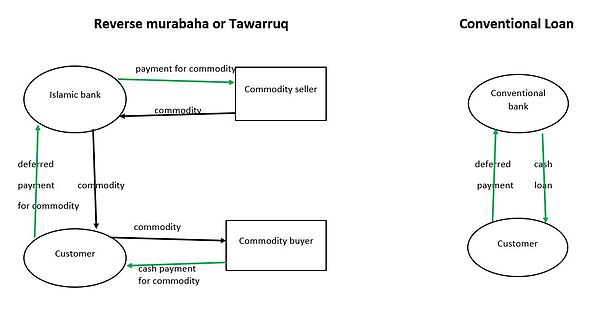

Tawarruq (also called a "reverse murabaha"[14] and sometimes a "commodity murabaha")[55] also allows the banking customer to borrow cash instead of finance a purchase,[56] and has also been criticized by some jurists.[57] Unlike a bay al-ina it involves another party in addition to the customer, Islamic bank and seller of the commodity. In Tawarruq the customer would buy some amount of a commodity (a commodity which is not a "medium of exchange" or forbidden in riba al-fadl such as gold, silver, wheat, barley, salt, etc.)[14] from the bank to be paid in installments over a period of time and sell that commodity on the spot market (the commodity buyer being the additional party) for cash.[54][58][59] (The commodity buying and selling is usually done by the bank on behalf of the customer,[14] so that "all that changes hands is papers being signed and then handed back" according to one researcher).[56] An example would be buying $10,000 worth of copper on credit for $12,000 to be paid over two years, and immediately selling that copper to the third party spot buyer for $10,000 in cash. There are additional fees involved for the commodity purchases and sales compared to a cash loan, but the additional $2000 is considered "profit" not "interest" and so not haram according to proponents.

According to Islamic banker Harris Irfan, this complication has "not persuaded the majority of scholars that this series of transactions is valid in the Sharia."[60][Note 5] Because the buying and selling of the commodities in Tawarruq served no functional purpose, banks/financers are strongly tempted to forgo it. Islamic scholars have noticed that while there have been "billions of dollars of commodity-based tawarruq transactions" there have not been a matching value of commodity being traded.[62] The IMF states that "tawarruq has become controversial among Shari’ah scholars because of its divergence of its use from the spirit of Islamic finance".[8] But some prominent scholars have tolerated commodity murabaha "for the growth of the [Islamic finance] industry".[6] Irfan states that (at least as of 2015) Sharia boards of some banks (such as Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank), have taken a stand against Tawarruq and were "looking at 'purer' forms of funding" (such as mudarabah).[63] To "counter the obvious violation of the spirit of the riba ban", some banks have required the complication (and expense) of two additional commodity brokers in addition to the customer and financier.[56][64]

On the other hand, Faleel Jamaldeen states that "commodity murabaha" contracts[55] are used to fund short-term liquidity requirements for Islamic interbank transactions,[55][65] although they may not use gold, silver, barley, salt, wheat or dates for commodities[66] as this is forbidden under Riba al-Fadl. Among the Islamic banks using Tawarruq (as of 2012) according to Jamaldeen, include the United Arab Bank, QNB Al Islamic, Standard Chartered of United Arab Emirates, and Bank Muaamalat of Malaysia.[14]

Legal status

[edit]United States

[edit]In the United States the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency—which regulates nationally licensed banks—has allowed murabaha:

Interpretive Letter #867. November 1999 ... In the current financial marketplace lending takes many forms . ... murabaha financing proposals are functionally equivalent to or a logical outgrowth of secured real estate lending and inventory and equipment financing, activities that are part of the business of banking.[67][68]

Challenges and criticism

[edit]Orthodox Islamic Scholars such as Taqi Usmani emphasize that murâbaḥah should only be used as a structure of last resort where profit and loss sharing instruments are unavailable.[25] Usmani himself describes murâbaḥah as a "borderline transaction" with "very fine lines of distinction" compared to an interest bearing loan, as "susceptible to misuse", and "not an ideal way of financing".[25] He laments that

Many institutions financing by way of murabahah determine their profit or mark-up on the basis of the current interest rate, mostly using LIBOR (Inter-bank offered rate in London) as the criterion.[21]

Another pioneer, Mohammad Najatuallah Siddiqui, has lamented that "as a result of diverting most of its funds towards murabaha, Islamic financial institutions may be failing in their expected role of mobilizing resources for development of the countries and communities they are serving,"[69] and even bringing about "a crisis of identity of the Islamic financial movement."[70][Note 6]

Some Muslims (Rakaan Kayali among others) complain that murabaha does not eliminate interest as it guarantees for itself the amount of profit it collects,[23] and so amounts to a Ḥiyal or legal "trick" to defeat the intent of shariah.[54] Khalid Zaheer considers it an example of how two classical shariah-compliant contracts (Murabahah and Bai Muajjal) can be combined to form a contract that is not compliant.[74]

Non-orthodox critics of murâbaḥah, have found the distinction of setting a price "against a commodity" as opposed to "against money" — with the first being allow and the second forbidden because "money has no intrinsic utility" — abstract or suspicious.[75] According to El-Gamal it has been called "merely inefficient lending".[61][Note 7] However criticism of the transaction has been primarily levied against its application. Critics complain that in most real world murâbaḥah transactions the commodities never change hands (the commodity never appears on the bank's balance sheet)[6] and sometimes there are no commodities at all, merely cash-flows between banks, brokers and borrowers. Often the commodity is completely irrelevant to the borrower's business and not even enough of the relevant commodities are in existence in the world to account for all the transactions taking place.[20] Frank Vogel and Samuel Hayes also note multi-billion-dollar murabaha transactions in London "popular for many years", where "many doubt the banks truly assume possession, even constructively, of inventory". [Note 8]

Islamic banker Irfan bemoans the fact that "not only is the murabaha money market insufficiently well developed and illiquid, but the very sharia compliance of it has come to be questioned", often by Islamic scholars not known for their strictness.[63]

Nejatullah Siddiqi warned the Islamic banking community that the alleged difference between modes of finance based on murabahah, bay' salam and conventional loans was even less than it appeared:

Some of these modes of finance are said to contain some elements of risk, but all these risks are insurable and are actually insured against. The uncertainty or risk to which the business being so financed is exposed is fully passed over to the other party. A financial system built solely around these modes of financing can hardly claim superiority over an interest-based system on grounds of equity, efficiency, stability and growth.[79]

Circa 1999 the Pakistan Federal Shariat Court ruled that the "mark-up system ... in vogue" among banks in Pakistan was against the Islamic injunctions.[28] Usmani noted (much like the complaints above) that the Pakistani banks failed to follow proper murabaha requirements—not actually buying a commodity or buying one "already owned by the customer".[80]

- Late payment

While in conventional finance late payments/delinquent loans are discouraged by accumulating interest, in Islamic finance control and management of late accounts has become a "vexing problems", according to Muhammad Akran Khan.[81] Others agree it is a problem.[35][36][Note 9] According to Ibrahim Warde,

Islamic banks face a serious problem with late payments, not to speak of outright defaults, since some people take advantage of every dilatory legal and religious device ... In most Islamic countries, various forms of penalties and late fees have been established, only to be outlawed or considered unenforceable. Late fees in particular have been assimilated to riba. As a result, 'debtors know that they can pay Islamic banks last since doing so involves no cost'[81][83]

Warde also complains that

"Many businessmen who had borrowed large amounts of money over long periods of time seized the opportunity of Islamicization to do away with accumulated interest of their debt, by repaying only the principal -- usually a puny sum when years of double-digit inflation were taken into consideration.[81][83]

Some suggestions to solve the problem include having the government or the central bank penalizing defaultors "by depriving them" of the use of "any financial institution" until they paid up (Taqi Usmani in Introduction to Islamic Finance) -- although this would require a completely Islamized society.[36] Collecting late fees but donating them to charity,[10][11][12] Collecting late fees only when the buyer "has deliberately refused to make a payment".[Note 10]

- Extra costs

Because murabaha financing is “asset-based” financing (and must be to avoid riba according to orthodox Islamic thinking), it requires financiers to purchase and sell properties. But regulatory frameworks in most countries forbid financial intermediaries such as banks "from owning or trading real properties" (according to scholar Mahmud El-Gamal).[84] Furthermore when the financier holds title to the property being sold it can be lost "if the financier is sued, loses, and declares bankruptcy", and this can happen when a customer has paid off most /almost all of the product/property’s price. To avoid these dangers SPVs (Special Purpose Vehicles) are created to hold title to the property and also "serve as parties to various agreements regarding obligations for repairs and insurance" as required by Islamic jurists. However, the SPVs entail extra costs usually not borne in conventional finance.[84]

- Example of Murâbaḥah

An example of a murabaha contract is: Adam approaches a Murabaha Bank in order to finance the purchase of a $10,000 automobile from “Cash-Only-Automobiles”. The bank agrees to purchase the automobile from “Cash-Only-Automobiles” for $10,000 and then sell it to Adam for $12,000 which is to be paid by Adam in equal installments over the next two years.

While the cost to Adam is approximately that of a 10% per year loan, the Murabaha Bank using this transaction maintain it is different because the amount that Adam owes is fixed and does not increase if he is delinquent on payments. Therefore, the finance is a sale for profit and not riba.

Another argument that murahaba is shariah compliant is that it is made up of two transactions, both halal (permissible):

Buying a car for $10,000 and selling it for $12,000 is allowed by Islam.

Making a purchase on a deferred payment basis is also allowed by Islam.

However, not mentioned here is the fact that the same car that is being sold for $12,000 on a deferred payment basis is being sold for $10,000 on a cash basis. So basically Adam has two options:

- “Cash-Only-Automobiles” will sell him the car for $10,000 but are not willing to wait to receive the full price.

- The Murabaha Bank will sell him the car for $12,000 and is willing to wait two years to receive the full price.

Adam’s choice to purchase from the Murabaha Bank reflects his desire to not pay the full price of the car today. In other words, he prefers to pay part of the price today and be indebted with the rest.

The Murabaha Bank agrees to be owed by Adam the price of his car in return for the amount that it is owed being $2,000 more than the price of the car today.

Did the bank charge Adam a predetermined return for the use of its money [interest]? Yes. The bank charged $2,000 in return for Adam’s use of its $10,000 to buy a car.

The fact that no penalties are assessed if Adam is delinquent on his payments simply means that the amount of interest in the murabaha contract is fixed at $2,000.[23] This amounts to a Ḥiyal or legal "trick" to defeat the intent of shariah.[54]

See also

[edit]- Islamic banking and finance

- Profit and loss sharing

- Islamic finance products, services and contracts

- Sharia and securities trading

- Muamalat

- FINCA Afghanistan, a Murâbaḥah-compliant microfinance institution (MFI)

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Faleel Jamaldeen insists that using LIBOR as a benchmark "doesn't mean that Islamic banks were charging an interest rate; they simply got guidance" from that rate of interest. Furthermore in late 2011 an Islamic Interbank Rate (IIBR) was developed and should "alleviated this source of controversy".[14] (see also "Thomson Reuters' "Islamic Interbank Benchmark Rate" -- IIBR. Is it really an important Step Forward for Islamic Finance Authenticity?")[15]

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol. 3, #282, Narrated [A'ishah: “The Prophet purchased food grains from a Jew on credit and mortgaged his iron armur to him”. (ishtara ta[aman min yahudi ila ajalin wa rahnahu dir[an min hadid; in al-Bukhari, Vol. 3, #309 the hadith is narrated with nasi’ah, instead of ajal)

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol. 3, #579, Narrated Jabir bin [Abdullah: “I went to the Prophet while he was in the Mosque. (Mis[ar thinks that Jabir went in the forenoon.) After the Prophet told me to pray two rak[ah, he repaid me the debt he owed me and gave me an extra amount”.

- ^

- "The first comprehensive report in this respect was submitted by the Council of Islamic Ideology in 1980.

- "The second report was that of the Commission for Islamization of Economy, constituted under the Shariat Act. This Commission has submitted its comprehensive report to the government in 1991.

- "Lastly, the same Commission was reconstituted under the Chairmanship of Raja Zafarul Haq which submitted its final report in August 1997."[33]

- ^ "...jurists of most schools have forbidden this transaction [tawarruq], which takes the form of multiple valid sales but does not serve the desired substance of Islamic law."[61]

- ^ M.O. Farooq,[71] quoting M. Iqbal and P. Molyneux[72] quoting M.N. Siddiqi[73]

- ^ Dr. Yusuf Al-Qaradawi, who described himself as one of the early supporters of Islamic banking, recently criticized many developments in the industry quite harshly. He was particularly critical of tawarruq, which is a natural extension of traditional murabaha financing; cf.[76]

- ^ "A number of scholars have recently cast doubts upon the acceptability of one of the most widely used forms of Islamic finance: the type of Murabaha trade financing practiced in London. These investors and well-known multinationals seeking lowest-cost working capital loans. Although these multi-billion-dollar contracts have been popular for many years, many doubt the banks truly assume possession, even constructively, of inventory, a key condition of a religiously acceptable murabaha. Without possession, these arrangements are condemned as nothing more than short-term conventional loans with a predetermined interest rate incorporated in the price at which the borrower repurchases the inventory. These 'synthetic' murabaha transactions are unacceptable to the devout Muslim, and accordingly there is now a movement away from murabaha investments of all types. Al-Rajhi Bank, al-Baraka, and the Government of Sudan are among the institutions that have vowed to phase out murabaha deals. This development creates difficulty: as Islamic banking now operates, murabaha trade financing is an indispensable tool."[77][78]

- ^ The Islamic Bankers Resource Centre also states that "for the longest time, Islamic Banks have been abused by delinquent customers due to the low penalties for late payments".[82]

- ^ Mumtaz Hussain, Asghar Shahmoradi, Rima Turk, writing for the IMF.[8]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Irfan, Harris (2015). Heaven's Bankers. Overlook Press. p. 135.

- ^ Usmani, Taqi (1998). An Introduction to Islamic Finance. Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0. p. 65. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ "Murabaha". Investopedia. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ^ a b c Jamaldeen, Islamic Finance For Dummies, 2012:188-9, 220-1

- ^ a b c d Islamic Finance: Instruments and Markets. Bloomsbury Publishing. 2010. p. 131. ISBN 9781849300391. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ a b c Irfan, Harris (2015). Heaven's Bankers. Overlook Press. p. 139.

- ^ "A Simple Introduction to Islamic Mortgages". 14 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Hussain, Mumtaz; Shahmoradi, Asghar; Turk, Rima (June 2015). IMF Working paper, An Overview of Islamic Finance (PDF). p. 8. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ "Late Payment Charges for Islamic Financial Institutions". Islamic Bankers : Resource Centre. 11 June 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ a b Visser, Hans, ed. (January 2009). "4.4 Islamic Contract Law". Islamic Finance: Principles and Practice. Edward Elgar. p. 77. ISBN 9781848449473. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

The prevalent position, however, seems to be that creditors may impose penalties for late payments, which have to be donated, whether by the creditor or directly by the client, to a charity, but a flat fee to be paid to the creditor as a recompense for the cost of collection is also acceptable to many fuqaha.

- ^ a b Kettell, Brian (2011). The Islamic Banking and Finance Workbook: Step-by-Step Exercises to help you ... Wiley. p. 38. ISBN 9781119990628. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

The bank can only impose penalties for late payment by agreeing to `purify` them by donating them to charity.

- ^ a b "FAQs and Ask a Question. Is it permissible for an Islamic bank to impose penalty for late payment?". al-Yusr. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ Visser, Hans (2013). Islamic Finance: Principles and Practice (Second ed.). Elgar Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 9781781001745. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Jamaldeen, Islamic Finance For Dummies, 2012:156

- ^ "Thomson Reuters' "Islamic Interbank Benchmark Rate" -- IIBR. Is it really an important Step Forward for Islamic Finance Authenticity?". Islamicmarkets.com. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ a b c Irfan, Harris (2015). Heaven's Bankers. Overlook Press. p. 136.

- ^ Siddiqui, M.N. (2002). Dialogue in Islamic Economics. Islamabad: Institute of Policy Studies. p. 175.

- ^ Farooq, Riba-Interest Equation and Islam, 2005: p.35-6

- ^ a b Usmani, Taqi (1998). An Introduction to Islamic Finance. Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0. p. 107. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

Therefore, it [Murabahah] should neither be taken as an ideal Islamic mode of financing, nor a universal instrument for all sorts of financing. It should be taken as a transitory step towards the ideal Islamic system of financing based on musharakah or mudarabah.

- ^ a b "Misused murabaha hurts industry". Arabian Business. 1 February 2008.

- ^ a b Usmani, Taqi (1998). An Introduction to Islamic Finance. Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0. p. 81. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ Murabaha Financing VS Lending on Interest| Qazi Irfan |July 22, 2008 | Social Science Research Network

- ^ a b c Kayali, Rakaan (11 March 2015). "Murabaha: Halal or Haram?". Practical Islamic Finance.

- ^ a b "Is charging more on credit sales (Murabaha) permissible?". Khalid Zaheer. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d Usmani, Historic Judgment on Interest, 1999: para 227

- ^ "Surah Al-Baqarah [2:275]". Surah Al-Baqarah [2:275]. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ Usmani, Historic Judgment on Interest, 1999: paras 50, 51, 219

- ^ a b Usmani, Historic Judgment on Interest, 1999: para 219

- ^ a b Usmani, Historic Judgment on Interest, 1999: para 223

- ^ a b Usmani, Historic Judgment on Interest, 1999: para 225

- ^ Jamaldeen, Islamic Finance For Dummies, 2012:220

- ^ Farooq, Riba, Interest and Six Hadiths, 2009: p.112

- ^ Usmani, Historic Judgment on Interest, 1999: para 228

- ^ Usmani, Historic Judgment on Interest, 1999: para 224

- ^ a b c PARKER, MUSHTAK (5 July 2010). "Payment delays and defaults". Arab News. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ a b c Usmani, Introduction to Islamic Finance, 1998: p.91

- ^ Ali, Muhammad Aqib. "The Roots & Development of Islamic Banking in the World & in Pakistan" (PDF). Proceeding - Kuala Lumpur International Business, Economics and Law Conference 7, Vol. 1, August 15–16, 2015: 122. ISBN 978-967-11350-6-8. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Usmani, Historic Judgment on Interest, 1999: para 190

- ^ a b Usmani, Introduction to Islamic Finance, 1998: p.73

- ^ Haltom, Renee. "Econ Focus. Islamic Banking, American Regulation (Second Quarter 2014)". Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ M. Kabir Hassan. "The Cost, profit and X-efficiency of Islamic Banks," 12th Annual Conference of Economic Research Forum, Egypt, 19–21 December 2005.

- ^ Irfan, Harris (2015). Heaven's Bankers: Inside the Hidden World of Islamic Finance. Little, Brown Book Group. p. 135. ISBN 9781472105066. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ Iqbal, Munawar, and Philip Molyneux. 2005. Thirty years of Islamic banking: History, performance and prospects. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ Kuran, Timur. 2004. Islam and Mammon: The economic predicaments of Islamism. Princeton, NJ; Princeton University Press

- ^ Lewis, M.K. and L.M. al-Gaud 2001. Islamic banking. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar

- ^ Yousef, T.M. 2004. The murabaha syndrome in Islamic finance: Laws, institutions and policies. In Politics of Islamic finance, ed. C.M. Henry and Rodney Wilson. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

- ^ "Government of Pakistan: Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

- ^ "MAKE PURCHASES WITH COST PLUS PROFIT (MURABAHA) CONTRACTS". dummies.com. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ "TRADE-BASED FINANCING MURABAHA (COST-PLUS SALE)" (PDF). Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ El-Gamal, Islamic Finance, 2006: p.18

- ^ Isa, Azrina Mohd. "Islamic Finance Contracts & Products". Skrine. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ Raza, Muhammad Tayyab. "Murabahah Finance". Islamic Banking - ABN AMRO (Pakistan) Limited. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ "Glossary of Financial Terms - B". Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance. Archived from the original on 29 August 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d Irfan, Harris (2015). Heaven's Bankers: Inside the Hidden World of Islamic Finance. Overlook Press. p. 137.

- ^ a b c Dusuki, Asyraf Wajdi (c. 2007). "Commodity Murabahah Programme (CMP): An Innovative Approach to Liquidity Management". Journal of Islamic Economics, Banking and Finance: 12.

- ^ a b c Khan, Islamic Banking in Pakistan, 2015: p.93

- ^ Bakir, Mohammad Majd (11 January 2014). "Islamic Finance | What is the Difference Between Bay' al-Tawarruq and Bay' al-Inah?". investment-and-finance.net. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ "What is the Difference Bay' al-Tawarruq and Bay' al-Inah?". Investment and Finance. 11 January 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ "Fiqh Muamalat. Bay' al-Tawarruq". scribd.com. Universiti Teknologi Mara. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ Irfan, Harris (2015). Heaven's Bankers: Inside the Hidden World of Islamic Finance. Overlook Press. p. 138.

- ^ a b El-Gamal, Islamic Finance, 2006: p.63

- ^ "Definition of tawarruq ft.com/lexicon". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ^ a b Irfan, Harris (2015). Heaven's Bankers: Inside the Hidden World of Islamic Finance. Overlook Press. p. 226.

- ^ "Ibrahim Warde presentation, Panel on Islamic Finance: Bankruptcy, Financial Distress and Debt Restructuring, Islamic Finance Workshop, Harvard Law School". 26 September 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Commodity Murabahah Programme". iimm.bnm.gov.my.

- ^ Jamaldeen, Islamic Finance For Dummies, 2012:155

- ^ "Interpretive Letter #867. 12 USC 24(7). 12 USC 29" (PDF). .occ.gov. Comptroller of the Currency. Administrator of National Banks. November 1999.

- ^ El-Gamal, Islamic Finance, 2006: p.15

- ^ SIDDIQI, Mohammad Nejatullah (2004). Riba, Bank Interest, and The Rationale of Its Prohibition (PDF). Visiting Scholars Research Series. Islamic Development Bank. p. 75. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Siddiqi, Muhammad Nejatullah (1988). Ariff, Mohamed (ed.). Islamic Banking in Southeast Asia: Islam and the Economic Development of ... Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 56. ISBN 9789971988982. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ Farooq, Riba-Interest Equation and Islam, 2005: p.35

- ^ Munawar IQBAL and Philip Molyneux. Thirty Years of Islamic Banking: History, Performance and Prospects, [Palgrave, 2005], p. 125

- ^ Mohammad Nejatullah SIDDIQI. Issues in Islamic Banking, [Leicester: The Islamic Foundation, UK, 1983]

- ^ Zaheer, Khalid. "Is Islamic Banking, in fact, Islamic?". Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ Usmani, Historic Judgment on Interest, 1999: para 224-5

- ^ Qaradawi [dead link]

- ^ Frank VOGEL and Samuel Hayes, III. Islamic Law and Finance: Religion, Risk and Return [The Hague: Kluwer Law International, 1998], pp.8-9

- ^ Farooq, Riba-Interest Equation and Islam, 2005: p.19

- ^ Mohammad Nejatullah SIDDIQI. Issues in Islamic Banking [Leicester: The Islamic Foundation, UK, 1983, p.52

- ^ Usmani, Historic Judgment on Interest, 1999: para 191

- ^ a b c Khan, What Is Wrong with Islamic Economics?, 2013: p.207-8

- ^ "Late Payment Charges for Islamic Financial Institutions". Islamic Bankers : Resource Centre. 11 June 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ a b Warde, Islamic finance in the global economy, 2000: p.163

- ^ a b El-Gamal, Islamic Finance, 2006: p.14, 64-5

Books, documents

[edit]- Farooq, Mohammad Omar. "The Riba-Interest Equation and Islam: Re-examination of the Traditional Arguments (November 2005, September 2009)" (PDF). Global Journal of Finance and Economics. 6 (2): 99–111. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Irfan, Harris (2015). Heaven's Bankers: Inside the Hidden World of Islamic Finance. Overlook Press.

- Jamaldeen, Faleel (2012). Islamic Finance For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118233900. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- el-Gamal, Mahmoud A. (2006). Islamic Finance : Law, Economics, and Practice (PDF). New York, NY: Cambridge. ISBN 9780521864145. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- Khan, Feisal (22 December 2015). Islamic Banking in Pakistan: Shariah-Compliant Finance and the Quest to Make Pakistan More Islamic. Routledge. ISBN 9781317366539. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- Khan, Muhammad Akram (2013). What Is Wrong with Islamic Economics?: Analysing the Present State and Future Agenda. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 9781782544159. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Turk, Rima A. (27–30 April 2014). Main Types and Risks of Islamic Banking Products (PDF). Kuwait: Regional Workshop on Islamic Banking. International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- Usmani, Taqi (1998). An Introduction to Islamic Finance (PDF). Kazakhstan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Usmani, Muhammad Taqi (December 1999). The Historic Judgment on Interest Delivered in the Supreme Court of Pakistan (PDF). Karachi, Pakistan: albalagh.net.