| Nephin | |

|---|---|

| Néifinn | |

Nephin with Lough Conn | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 806 m (2,644 ft) |

| Prominence | 778 m (2,552 ft) |

| Listing | P600, Marilyn, Hewitt |

| Coordinates | 54°00′43″N 9°22′05″W / 54.012°N 9.368°W |

| Geography | |

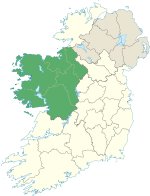

| Location | County Mayo, Ireland |

| OSI/OSNI grid | G103079 |

Nephin or Nefin[1][2] (Irish: Néifinn), at 806 metres (2646 ft), is the highest standalone mountain in Ireland and the second-highest peak in Connacht (after Mweelrea). It is to the west of Lough Conn in County Mayo. Néifinn is variously translated as meaning 'heavenly', 'sanctuary', or "Finn's Heaven".

Location

[edit]It lies in the centre of Gleann Néifinne, a district bounded by Lough Conn to the east, the Windy Gap/Barnageehy to the south, and Birreencorragh mountain to the west. Its northern limit was in 1838 noted as the townland of Ballybrinoge in the parish of Crossmolina. However, a prose tract of the 14th/15th century makes clear that its northern and western borders were contracted during the later medieval era.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

Nephin is mentioned in Cath Maige Tuired ("The Battle of Moytura") as one of the "twelve chief mountains" of Ireland. In the text it is called Nemthenn. This name may be related to nemeton, a term for a sacred space in Celtic polytheism.[3]

In antiquity, the area was inhabited by the Gamarad, who were Kings of Connacht in prehistory. One of their kings, Ailill Finn, is stated to have held residence at Dun Atha Fene, now Caorthannan/Castlehill townland, in the parish of Addergoole and Crossmolina. The legend of the Táin Bó Flidhais tells the story of a cattle raid on Ailill Finn and his wife Flidais otherwise known as The Mayo Táin.

The mountain's importance may be inferred by the decision at the Synod of Raith Bressail in 1111 to make Nephin the northern boundary of the diocese of Cong. Gleann Neimhthinne is stated by John O'Donovan as being one of the seven constituent parts of Tirawley, the others being An Lagan, Breadach, Calraighe Maighe nEleag, Caoille Conaill, Ui Eathach Muaidhe and An Da Bhac.

In Leabhar Fiachrach, a topographical and genealogical tract written by Giolla Iosa Mor Mac Fhirbhisigh about 1400, the areas early peoples and families are listed thus:

- Clann Mhuireadhaigh mec Fearghusa mec Amhalghaidh – descended from Muireadhach, a king of Ui Amhalghaidh, a branch of the Connachta.

- O Lachtna – 12th century lords of An Da Bhac and Glen Nephin, rendered O Lachtnain, Loughnane, Loughney, Loftus.

King Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair of Connacht (1088–1156) intruded his vassals and kinsmen, the Mac Diarmada of Moylurg, as a colony in the area, and into Ui Maill, in the first half of the 12th century. After the Anglo-Norman conquest of Connacht (c.1237–1270), the Clann Ricinh Baireid expelled the O Lachtnain chiefs, and became its new owners. They in turn were gradually squeezed out the Barrett family in the second half of the 14th century by the Bourke descendants of Sir Edmond Albanach de Burgh (died 1375). Do Bhreathnuib in Ibh Amhalghaidh mec Fiachrach tract commonly referred to as The Welshmen of Tirawley, preserves tradition concerning the settlement of Glen Nephin by William Mor na Maighne Barrett (fl. 1267), and a gruesome account of a long conflict between the Bourkes, the Barretts, and tenants of the latter clan, the Lynnots.

In the first half of the 17th century the proprietors were still members of the Barrett and Bourke clans. In 1632 Myler, son of Pierce Barrett of Ballysakeery, sold most of his lands to Tibbot and Walter Bourke of Turlough, Castlebar. After the end of the Irish Confederate Wars in 1653, Cromwellian forces confiscated the land from Barrett and Bourke alike. In 1666, Dubhaltach Mac Fhirbhisigh stated that "now there is neither Barrett nor Burke, not to mention Clann fiachrach, in possession of any lands there." Its new owners were named Jackson, Gore, Hadsor, and others.

Glen Nephin remained Gaeltacht into the second half of the 19th century.

In media

[edit]Mount Nephin was included in the 2020 movie Wild Mountain Thyme.

See also

[edit]- Lists of mountains in Ireland

- List of Irish counties by highest point

- List of mountains of the British Isles by height

- List of P600 mountains in the British Isles

- List of Marilyns in the British Isles

- List of Hewitt mountains in England, Wales and Ireland

References

[edit]- ^ M'Parlan, J.; Dublin Society (1802). Statistical Survey of the County of Mayo: With Observations on the Means of Improvement : Drawn Up in the Year 1801, for the Consideration, and Under the Direction of the Dublin Society. Goldsmiths'-Kress library of economic literature. Graisberry and Campbell.

- ^ Hyde, D. (1971). The Love Songs of Connacht: Being the Fourth Chapter of the Songs of Connacht. Irish University Press. ISBN 978-0-7165-1329-2.

- ^ Tempan, Paul. Irish Hill and Mountain Names. MountainViews.ie.

- Historical Note of the Medieval Territory of Gleann Neimhthinne, Tomas G. O Cannan, Cathair na Mart 20, pp. 118–128, Westport, County Mayo, 2000