The New Testament narrative of the life of Jesus refers to several locations in the Holy Land and a Flight into Egypt. In these accounts the principal locations for the ministry of Jesus were Galilee and Judea, with activities also taking place in surrounding areas such as Perea and Samaria.[1] Other places of interest to scholars include locations such as Caesarea Maritima where in 1961 the Pilate stone was discovered as the only archaeological item that mentions the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate, by whose order Jesus was crucified.[2][3]

The narrative of the ministry of Jesus in the Gospels is usually separated into sections that have a geographical nature: his Galilean ministry follows his baptism and continues in Galilee and surrounding areas until the death of John the Baptist.[1][4] This phase of activities in the Galilee area draws to an end approximately in Matthew 17 and Mark 9. After the death of John the Baptist and Jesus' proclamation as Christ by Peter, his ministry continues along his final journey towards Jerusalem through Perea and Judea.[5][6] The journey ends with his triumphal entry into Jerusalem in Matthew 21 and Mark 11. The final part of Jesus' ministry then takes place during his last week in Jerusalem which ends in his crucifixion.[7]

Geography and ministry

[edit]

In the New Testament accounts, the principal locations for the ministry of Jesus were Galilee and Judea, with activities also taking place in surrounding areas such as Perea and Samaria.[1][4] The gospel narrative of the ministry of Jesus is traditionally separated into sections that have a geographical nature.

- Galilean ministry

- Jesus' ministry begins when after his baptism, he returns to Galilee and preaches in the synagogue of Capernaum.[8][9] The first disciples of Jesus encounter him near the Sea of Galilee, and his later Galilean ministry includes key episodes such as Sermon on the Mount (with the Beatitudes) which form the core of his moral teachings.[10][11] Jesus' ministry in the Galilee area draws to an end with the death of John the Baptist.[12][13]

- Journey to Jerusalem

- After the death of John the Baptist, about halfway through the Gospels (approximately Matthew 17 and Mark 9) two key events take place that change the nature of the narrative by beginning the gradual revelation of his identity to his disciples: his proclamation as Christ by Peter and his transfiguration.[5][6] After these events, a good portion of the Gospel narratives deal with Jesus' final journey to Jerusalem through Perea and Judea.[5][6][14][15] As Jesus travels towards Jerusalem through Perea he returns to the area where he was baptized.[16][17][18]

- Final week in Jerusalem

- The final part of Jesus' ministry begins (Matthew 21 and Mark 11) with his triumphal entry into Jerusalem after the raising of Lazarus which takes place in Bethany. The Gospels provide more details about the final portion than the other periods, devoting about one third of their text to the last week of the life of Jesus in Jerusalem which ends in his crucifixion.[7]

- Post-Resurrection appearances

- The New Testament accounts of the resurrection appearances of Jesus and his ascension place him both in the Judea and the Galilee area.

Locations

[edit]Galilee

[edit]

- Bethsaida: Mark 8:22–26 includes the account of the healing of the "Blind man of Bethsaida".[19]

- Cana: John 2:1–11 includes the marriage at Cana during which Jesus performs his first miracle.[20][21]

- Capernaum: The pericope of Jesus in the synagogue of Capernaum amounts to the beginning of the public ministry of Jesus in the New Testament narrative.[8] Capernaum is mentioned in the Gospels several times, and events such as healing the paralytic at Capernaum take place there.[22]

- Chorazin: In Matthew 11:23 and Luke 10:13–15 this village in Galilee appears in the context of the rejection of Jesus.

- Gennesaret: This town (which no longer exists) was on the northwestern shore of the Sea of Galilee. The town was perhaps halfway between Capernaum and Magdala.[23] The town is mentioned during Jesus' healing ministry in Gennesaret recorded in Matthew 14:34–36 and Mark 6:53–56.

- Mount of Transfiguration: The location of the mountain for the transfiguration of Jesus is debated among scholars, and locations such as Mount Tabor have been suggested.[24]

- Nain: The pericope of young man from Nain appears in Luke 7:11–17.[25] This is the first of three instances in the Gospels in which Jesus raises the dead.

- Nazareth: Nazareth is where young Jesus grows up and where he is found in the Temple by his parents.[26]

- Sea of Galilee: The lake features prominently throughout the New Testament narrative, from the beginning of his ministry to the end. The calling of his first disciples takes place on the shores of this lake.[27][28] Towards the end of the narrative, in the second miraculous catch of fish, a resurrected Jesus appears to his apostles again.[29][30]

Decapolis and Perea

[edit]- Bethabara: The Gospel of John (1:28) states that John the Baptist was baptizing in "Bethany beyond the Jordan".[31] This is not the village Bethany just east of Jerusalem, but the town Bethany, also called Bethabara in Perea.[32] A different interpretation places Bethabara on the opposite, western bank of the Jordan, in Judea rather than Perea; best known among these is the Madaba Map, which places Betahbara at today's west side of Al-Maghtas, officially known as Qasr el-Yahud.

- Decapolis: The healing the deaf mute of Decapolis takes place in this area.[33]

- Gerasa (also Gergesa or Gadara) is the location of the exorcism of the Gerasene demoniac in Mark 5:1–20, Matthew 8:28–34, and Luke 8:26–39.[34]

Samaria

[edit]- Ænon: The Gospel of John (3:23) refers to Enon near Salim as the place where John the Baptist performs baptisms in the River Jordan, "because there was much water there".[31][32]

- Caesarea Maritima: This port city is the location of the 1961 discovery of the Pilate stone, the only archaeological item that mentions the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate, by whose order Jesus was crucified.[2][3][35]

- Sychar: The encounter with the Samaritan woman at the well in John 4:4–26 takes place in Sychar in Samaria near Jacob's Well.[36] This is the location of the Water of Life Discourse in John 4:10–26.[37]

Judea

[edit]- Bethany (near Jerusalem): The raising of Lazarus, shortly before Jesus enters Jerusalem for the last time, takes place in Bethany.[38]

- Bethesda: In John 5:1–18, the healing of the paralytic takes place at the Pool of Bethesda in Jerusalem.[39]

- Bethlehem: The Gospel of Luke (2:1-7) states that the birth of Jesus took place in Bethlehem.[40][41]

- Bethphage is mentioned as the place from which Jesus sent the disciples to find a donkey for the triumphal entry into Jerusalem. Matthew 21:1; Mark 11:1; Luke 19:29 mention it as close to Bethany.[42][43] Eusebius of Caesarea (Onomasticon 58:13) located it on the Mount of Olives.[43]

- Calvary (Golgotha): Calvary is the Latin term for Golgotha the Greek translation of the Aramaic term for the place of the skull—the location of the crucifixion of Jesus.[44]

- Emmaus: Jesus appears to two disciples on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24:13–32) and eats supper with them.[45][46]

- Gabbatha (Lithostrōtos): This location is referenced only once in the New Testament in John 19:13.[47][48] This is an Aramaic term that refers to the location of the trial of Jesus by Pontius Pilate, and the Greek name of Lithostrōtos (λιθόστρωτος) meaning stone pavement also refers to it. It was likely a raised stone platform where Jesus faced Pilate.[47] James Charlesworth considers this location of high archaeological significance and states that modern scholars believe this location was in the public square just outside the Praetorium in Jerusalem and was paved with large stones.[49]

- Gethsemane: Immediately after the Last Supper, Jesus and his disciples go to the garden at Gethsemane, the location of his agony in the garden and his arrest.[50]

- Jericho: The healing the blind Bartimaeus occurs near Jericho.[51]

- Mount of Olives: This mountain appears in several New Testament passaages, and the Olivet Discourse is named after it. During his triumphal entry into Jerusalem, Jesus descends from the Mount of Olives towards Jerusalem, and the crowds lay their clothes on the ground to welcome him.[52] In Acts 1:9-12, the ascension of Jesus takes place near this mountain.

- Temple in Jerusalem: The Temple is featured in the cleansing of the Temple incident, where Jesus expels the money changers.[53]

Other places

[edit]- Egypt: The Flight to Egypt episode in the Gospel of Matthew takes place after the birth of Jesus, and the family flees to Egypt before returning to Galilee a few years later.[54][55][56]

- "The region of Tyre and Sidon" (Mark 7:24–30 and Matthew 15:21–28) in what had once been Phoenicia and had become in Jesus' time part of Roman Syria, today situated in Southern Lebanon. There Jesus exorcises a demon from the daughter of a Syrophoenician woman.

- Caesarea Phillippi ("the villages around Caesarea Philippi"): the capital city of the tetrarchy of Philip is mentioned in Mark 8:27 and its surroundings are the first location where Jesus predicts his death (Mark 8:31).[57] This area is also important in the New Testament because, just before entering it, Jesus asks his disciples "who do you think that I am?", producing the "You are the Christ of God" response from Apostle Peter in Matthew 16:13-20, Mark 8:27-29 and Luke 9:18-20.[58][59]

- Road to Damascus: In the Acts of the Apostles (9, 22 and 26), this road is the location for the conversion of the Apostle Paul, during which the resurrected Jesus appears to him. [60][61]

Archaeology

[edit]

No documents written by Jesus exist,[64] and no specific archaeological remnants are directly attributed to him. The 21st century has witnessed an increase in scholarly interest in the integrated use of archaeology as an additional research component in arriving at a better understanding of the historical Jesus by illuminating the socio-economic and political background of his age.[65][66][67][68][69][70]

James Charlesworth states that few modern scholars now want to overlook the archaeological discoveries that clarify the nature of life in Galilee and Judea during the time of Jesus.[68] Jonathan Reed states that chief contribution of archaeology to the study of the historical Jesus is the reconstruction of his social world.[71] An example archaeological item that Reed mentions is the 1961 discovery of the Pilate stone, which mentions the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate, by whose order Jesus was crucified.[71][72][73]

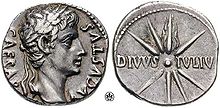

Reed also states that archaeological finding related to coinage can shed light on historical critical analysis. As an example, he refers to coins with the ""Divi filius" inscription.[65] Although Roman Emperor Augustus called himself "Divi filius", and not "Dei filius" (Son of God), the line between being god and god-like was at times less than clear to the population at large, and the Roman court seems to have been aware of the necessity of keeping the ambiguity.[62][63] Later, Tiberius who was emperor at the time of Jesus came to be accepted as the son of divus Augustus.[62] Reed discusses this coinage in the context of Mark 12:13–17 in which Jesus asks his disciples to look at a coin: "Whose portrait is this? And whose inscription?" and then advises them to "Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar's, and unto God the things that are God's." Reed states that "the answer becomes much more subversive when one knows that Roman coinage proclaimed Caesar to be God".[65]

David Gowler states that an interdisciplinary scholarly study of archeology, textual analysis and historical context can shed light on Jesus and his teachings.[69] An example is the archeological studies at Capernaum. Despite the frequent references to Capernaum in the New Testament, little is said about it there.[74] However, recent archeological evidence show that unlike earlier assumptions, Capernaum was poor and small, without even a forum or agora.[69][75] This archaeological discovery thus resonates well with the scholarly view that Jesus advocated reciprocal sharing among the destitute in that area of Galilee.[69] Other archeological findings support the wealth of the ruling priests in Judea at the beginning of the first century.[67][76]

See also

[edit]- Chronology of Jesus

- Detailed Christian timeline

- Gospel harmony

- Historical Jesus

- Jesus in Christianity

- Life of Christ in art

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Macmillan Bible Atlas

- Timeline of the Bible

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Christianity: an introduction by Alister E. McGrath 2006, ISBN 978-1-4051-0901-7, pp. 16–22.

- ^ a b Historical Dictionary of Jesus by Daniel J. Harrington 2010 ISBN 0810876671 page 32

- ^ a b Archaeology and the Galilean Jesus: a re-examination of the evidence by Jonathan L. Reed, 2002, ISBN 1563383942, p. 18.

- ^ a b The Life and Ministry of Jesus: The Gospels by Douglas Redford 2007 ISBN 0-7847-1900-4 pages 117-130

- ^ a b c The Christology of Mark's Gospel by Jack Dean Kingsbury 1983 ISBN 0-8006-2337-1 pages 91-95

- ^ a b c The Cambridge companion to the Gospels by Stephen C. Barton ISBN 0-521-00261-3 pages 132-133

- ^ a b Matthew by David L. Turner, 2008, ISBN 0-8010-2684-9, p. 613.

- ^ a b Jesus in the Synagogue of Capernaum: The Pericope and its Programmatic Character for the Gospel of Mark by John Chijioke Iwe 1991 ISBN 9788876528460 page 7

- ^ The Gospel according to Matthew by Leon Morris ISBN 0-85111-338-9 page 71

- ^ The Sermon on the mount: a theological investigation by Carl G. Vaught 2001 ISBN 978-0-918954-76-3 pages xi-xiv

- ^ The Synoptics: Matthew, Mark, Luke by Ján Majerník, Joseph Ponessa, Laurie Watson Manhardt, 2005, ISBN 1-931018-31-6, pages 63–68

- ^ Steven L. Cox, Kendell H Easley, 2008 Harmony of the Gospels ISBN 0-8054-9444-8 pages 97-110

- ^ The Life and Ministry of Jesus: The Gospels by Douglas Redford 2007 ISBN 0-7847-1900-4 pages 165-180

- ^ Steven L. Cox, Kendell H Easley, 2007 Harmony of the Gospels ISBN 0-8054-9444-8 pages 121-135

- ^ The Life and Ministry of Jesus: The Gospels by Douglas Redford 2007 ISBN 0-7847-1900-4 pages 189-207

- ^ Steven L. Cox, Kendell H Easley, 2007 Harmony of the Gospels ISBN 0-8054-9444-8 page 137

- ^ The Life and Ministry of Jesus: The Gospels by Douglas Redford 2007 ISBN 0-7847-1900-4 pages 211-229

- ^ Mercer dictionary of the Bible by Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard 1998 ISBN 0-86554-373-9 page 929

- ^ The Miracles of Jesus by Craig Blomberg, David Wenham 2003 ISBN 1592442854 page 419

- ^ H. Van der Loos, 1965 The Miracles of Jesus, E.J. Brill Press, Netherlands page 599

- ^ Dmitri Royster 1999 The miracles of Christ ISBN 0881411930 page 71

- ^ The Miracles of Jesus by Craig Blomberg, David Wenham 2003 ISBN 1592442854 page 440

- ^ Lamar Williamson 1983 Mark ISBN 0804231214 pages 129-130

- ^ B. Meistermann, "Transfiguration", The Catholic Encyclopedia, XV, New York: Robert Appleton Company

- ^ Luke by Fred Craddock 2009 ISBN 0664234356 page 98

- ^ The Bible Knowledge Commentary: New Testament edition by John F. Walvoord, Roy B. Zuck 1983 ISBN 0882078127 page 210

- ^ The Gospel according to Matthew by Leon Morris 1992 ISBN 0851113389 pages 83

- ^ Luke by Fred B. Craddock 1991 ISBN 0804231230 page 69

- ^ J.W. Wenham, The Elements of New Testament Greek, Cambridge University Press, 1965, p. 75.

- ^ Boyce W. Blackwelder, Light from the Greek New Testament, Baker Book House, 1976, p. 120, ISBN 0801006627

- ^ a b Big Picture of the Bible - New Testament by Lorna Daniels Nichols 2009 ISBN 1-57921-928-4 page 12

- ^ a b John by Gerard Stephen Sloyan 1987 ISBN 0-8042-3125-7 page 11

- ^ Lamar Williamson 1983 Mark ISBN 0804231214 pages 138-140

- ^ The Life and Ministry of Jesus: The Gospels by Douglas Redford 2007 ISBN 0-7847-1900-4 page 168

- ^ Studying the historical Jesus: evaluations of the state of current research by Bruce Chilton, Craig A. Evans 1998 ISBN 9004111425 page 465

- ^ The Gospel of John by Joseph Ponessa, Laurie Watson Manhardt 2005 ISBN 1931018251 page 39

- ^ The Gospel According to St. John: An Introduction With Commentary and Notes by C. K. Barrett 1955 ISBN 0664221807 page 12

- ^ Francis J. Moloney, Daniel J. Harrington, 1998 The Gospel of John Liturgical Press ISBN 0814658067 page 325

- ^ The Miracles of Jesus by Craig Blomberg, David Wenham 2003 ISBN 1592442854 page 462

- ^ Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (1998). Mercer dictionary of the Bible. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press. p. 556. ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7

- ^ Marsh, Clive; Moyise, Steve (2006). Jesus and the Gospels. New York: Clark International. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-567-04073-2.

- ^ The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700 by Jerome Murphy-O'Connor 2008 ISBN 0199236666 page 150

- ^ a b Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land by Avraham Negev 2005 ISBN 0826485715 page 80

- ^ Encountering John: The Gospel in Historical, Literary, and Theological Perspective by Andreas J. Köstenberger 2002 ISBN 0801026032 page 181

- ^ Luke by Fred Craddock 1991 ISBN 0-8042-3123-0 page 284

- ^ Exploring the Gospel of Luke: an expository commentary by John Phillips 2005 ISBN 0-8254-3377-0 pages 297-230

- ^ a b Historical Dictionary of Jesus by Daniel J. Harrington 2010 ISBN 0810876671 page 62

- ^ Jesus and archaeology edited by James H. Charlesworth 2006 ISBN 080284880X pages 34 and 573

- ^ Jesus and archaeology edited by James H. Charlesworth 2006 ISBN 080284880X pages 34

- ^ Bible Exposition Commentary, Vol. 1: New Testament by Warren W. Wiersbe 1992 ISBN 1564760308 pages 268-269

- ^ Mary Ann Tolbert, Sowing the Gospel: Mark's World in Literary-Historical Perspective 1996, Fortress Press. p189

- ^ The people's New Testament commentary by M. Eugene Boring, Fred B. Craddock 2004 ISBN 0-664-22754-6 pages 256-258

- ^ The Bible knowledge background commentary by Craig A. Evans 2005 ISBN 0-7814-4228-1 page 49

- ^ Steven L. Cox, Kendell H Easley, 2007 Harmony of the Gospels ISBN 0-8054-9444-8 pages 30-37

- ^ Who's Who in the New Testament by Ronald Brownrigg, Canon Brownrigg 2001 ISBN 0-415-26036-1 pages 96-100

- ^ The Birth of Jesus According to the Gospels by Joseph F. Kelly 2008 ISBN pages 41-49

- ^ The Gospel according to Mark: meaning and message by George Martin 2005 ISBN 0829419705 pages 200-202

- ^ The Gospel of Mark, Volume 2 by John R. Donahue, Daniel J. Harrington 2002 ISBN 0-8146-5965-9 page 336

- ^ The Collegeville Bible Commentary: New Testament by Robert J. Karris 1992 ISBN 0-8146-2211-9 pages 885-886

- ^ Bromiley, Geoffrey William (1979). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: A-D ISBN 0-8028-3781-6 page 689

- ^ Barnett, Paul (2002) Jesus, the Rise of Early Christianity InterVarsity Press ISBN 0-8308-2699-8 page 21

- ^ a b c Early Christian literature by Helen Rhee 2005 ISBN 0-415-35488-9 pages 159-161

- ^ a b Experiencing Rome: culture, identity and power in the Roman Empire by Janet Huskinson 1999 ISBN 978-0-415-21284-7 page 81

- ^ Christology: A Biblical, Historical, and Systematic Study of Jesus by Gerald O'Collins 2009 ISBN 0-19-955787-X pages 1-3 "As regards the 'things which Jesus did', let me note that he left no letters or other personal documents."—page 2

- ^ a b c Jonathan L. Reed, "Archaeological contributions to the study of Jesus and the Gospels" in The Historical Jesus in Context edited by Amy-Jill Levine et al. Princeton Univ Press 2006 ISBN 978-0-691-00992-6 pages 40-47

- ^ Archaeology and the Galilean Jesus: a re-examination of the evidence by Jonathan L. Reed 2002 ISBN 1-56338-394-2 pages xi-xii

- ^ a b Craig A. Evans (Mar 26, 2012). The Archaeological Evidence For Jesus.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Jesus Research and Archaeology: A New Perspective" by James H. Charlesworth in Jesus and archaeology edited by James H. Charlesworth 2006 ISBN 0-8028-4880-X pages 11-15

- ^ a b c d What are they saying about the historical Jesus? by David B. Gowler 2007 ISBN 0-8091-4445-X page 102

- ^ Craig A. Evans (Mar 16, 2012). Jesus and His World: The Archaeological Evidence. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-23413-3.

- ^ a b Archaeology and the Galilean Jesus: a re-examination of the evidence by Jonathan L. Reed 2002 ISBN 1-56338-394-2 page 18

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Jesus by Daniel J. Harrington 2010 ISBN 0-8108-7667-1 page 32

- ^ Studying the historical Jesus: evaluations of the state of current research by Bruce Chilton, Craig A. Evans 1998 ISBN 90-04-11142-5 page 465

- ^ "Jesus and Capernaum: Archeological and Gospel Stratigraohy" in Archaeology and the Galilean Jesus: a re-examination of the evidence by Jonathan L. Reed 2002 ISBN 1-56338-394-2 page 139-156

- ^ Jesus and archaeology edited by James H. Charlesworth 2006 ISBN 0-8028-4880-X page 127

- ^ Who Was Jesus? by Paul Copan and Craig A. Evans 2001 ISBN 0-664-22462-8 page 187