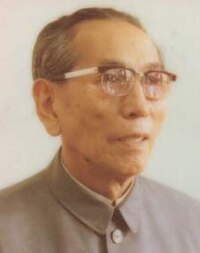

Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme | |

|---|---|

| ང་ཕོད་ངག་དབང་འཇིགས་མེད་ 阿沛·阿旺晋美 | |

| |

| Vice Chairman of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference | |

| In office 27 March 1993 – 23 December 2009 | |

| Chairman | Li Ruihuan→Jia Qinglin |

| In office 29 April 1959 – 5 January 1965 | |

| Chairman | Zhou Enlai |

| Chairman of the Tibet Autonomous Region People's Congress | |

| In office February 1983 – January 1993 | |

| Preceded by | Yang Dongsheng |

| Succeeded by | Raidi |

| In office August 1979 – April 1981 | |

| Preceded by | new position |

| Succeeded by | Yang Dongsheng |

| Chairman of the Tibet Autonomous Region | |

| In office 1964–1968 | |

| Preceded by | Choekyi Gyaltsen |

| Succeeded by | Zeng Yongya |

| In office 1981–1983 | |

| Preceded by | Sanggyai Yexe |

| Succeeded by | Doje Cedain |

| Vice Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress | |

| In office 3 January 1965 – 27 March 1993 | |

| Chairman | Zhu De→Ye Jianying→Peng Zhen→Wan Li |

| Delegate to the National People's Congress | |

| In office September 1954 – December 1964 | |

| Chairman | Liu Shaoqi→Zhu De |

| Kalön of Tibet | |

| In office 1950–1959 Serving with Thupten Kunkhen (until 1951), Kashopa Chogyal Nyima (1945–1949), Lhalu Tsewang Dorje (1946–1952), Dogan Penjor Rabgye (1949–1957), Khyenrab Wangchug (1951–1956), Liushar Thubten Tharpa (since 1955), Sampho Tsewang Rigzin (since 1957), and Surkhang Wangchen Gelek | |

| Monarch | 14th Dalai Lama |

| Governor of Domai | |

| In office August 1950 – October 1950 | |

| Monarch | 14th Dalai Lama |

| Preceded by | Lhalu Tsewang Dorje |

| Succeeded by | title abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 1, 1910 Lhasa, Tibet, Qing Empire |

| Died | December 23, 2009 (aged 99) Beijing, People's Republic of China |

| Spouse | Ngapoi Cedain Zhoigar |

| Awards | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Deputy Commander, PLA Tibet Military District Kalön (minister), Kashag Commander-in-chief, Tibetan Army in Chamdo |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Chamdo |

Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme (Tibetan: ང་ཕོད་ངག་དབང་འཇིགས་མེད་, Wylie: Nga phod Ngag dbang 'jigs med[1], ZYPY: Ngapo Ngawang Jigmê, Lhasa dialect: [ŋɑ̀pø̂ː ŋɑ̀wɑŋ t͡ɕíʔmi]; Chinese: 阿沛·阿旺晋美[1]; pinyin: Āpèi Āwàng Jìnměi; February 1, 1910 – December 23, 2009[2]) was a Tibetan senior official who assumed various military and political responsibilities both before and after 1951 in Tibet. He is often known simply as Ngapo in English sources.

Early life

[edit]Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme was born in Karma Gorge of Lhasa as the son of a leading Tibetan aristocratic family descended from former kings of Tibet, the Horkhang.[3] His father was governor of Chamdo in Eastern Tibet and commander of the Tibetan armed forces.[4] After studying traditional Tibetan literature, he went to Britain for further education.[5][better source needed] He was married to Ngapoi Cedain Zhoigar, Vice President of the Tibetan Women's Federation,[6] hence his name Ngapoi.[note 1]

Career

[edit]Upon returning in 1932 from his studies in Britain, he served in the Tibetan army. Ngapoi began his career as a local official in Chamdo in 1936. As a cabinet member of the former government of Tibet under the Dalai Lama, he advocated reform. In April 1950 he was appointed governor-general (commissioner) of Chamdo, but took office only in September, after the previous governor, Lhalu, had left for Lhasa.[7]

| Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme | |||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tibetan | ང་ཕོད་ངག་དབང་འཇིགས་མེད་ | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 阿沛·阿旺晉美 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 阿沛·阿旺晋美 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Commander-in-chief of the Tibetan Army at Chamdo

[edit]While serving as governor-general of Chamdo, he also became commander-in-chief of the Tibetan Army.[5][6]

While his predecessor, Lhalu, had made elaborate military plans and fortifications and asked the Kashag for more soldiers and weapons to stop the People's Liberation Army from entering Tibet, Ngapoi had the fortifications removed, refused to hire Khampa warriors and to install two portable wireless sets as he thought it was better to negotiate.[7]

In October 1950, his forces confronted the People's Liberation Army. The battle was quickly over. As he had warned before his departure for Chamdo, "the Tibetan forces were no match for the PLA who [...] had liberated the whole of China by defeating several million Kuomintang soldiers".[8] Ngapoi surrendered Chamdo to the Chinese. The PLA surprised him by treating him well and giving him long lectures on the New China's policies toward minor nationalities. Within a year, he was the deputy commander-in-chief for the PLA forces in Tibet. He became a leader not only of Tibet but also the Chinese Communist Party in Tibet.[9]

Head of the Tibetan Delegation to the Beijing Peace Negotiations

[edit]

As a delegate of the government of Tibet sent to negotiate with the Chinese Government,[10] he headed the Tibetan delegation to the Beijing peace negotiations in 1951, where he signed the Seventeen Point Agreement[11] with the Chinese Communist government in 1951, accepting Chinese sovereignty[12] in exchange for guarantees of autonomy and religious freedom.

The validity of his acceptance on behalf of the Tibetan government has been questioned. The Tibetan exiled community claims that his signature of the Agreement was obtained under duress, and that, as only the governor of Chamdo, signature of the agreement exceeded his powers of representation and is therefore invalid.[13]

In his biography My Land and My People, the Dalai Lama claims that in 1952, the acting Tibetan Prime Minister Lukhangwa told Chinese representative Zhang Jingwu that the Tibetan "people did not accept the agreement".[14]

However, according to Sambo Rimshi, one of the Tibetan negotiators,[15] the Tibetan delegation, including Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme, went to Beijing with the Dalai Lama's authorization and instructions[16][17] As Sambo Rimchi recalled, Dalai Lama's instruction to the negotiators clearly states:

Here are ten points. I have faith that you will not do anything bad, so you should go and achieve whatever you can.[15]

According to Sambo, the young Dalai Lama also told the negotiators to use their best judgment according to the situation and circumstances and report back to the Kashag in Yadong. Sambo recalled that the negotiators brought a secret codebook so that they could establish a wireless link with Yadong and discuss issues as they arose.[18] According to historians Tom A. Grunfeld, Melvyn C. Goldstein and Tsering Shakya, the young Dalai Lama did ratify the Seventeen Point agreement with Tsongdu Assembly's recommendation few months after the signing.[19][20][21]

In 1959, the Dalai Lama on his arrival in India after he fled Tibet repudiated the "17-point Agreement" as having been "thrust upon Tibetan Government and people by the threat of arms".[22]

An advocate of reform

[edit]Ngapoi Ngawang Jigmé was one of a small number of progressive elite Tibetans that were eager to modernize Tibet and saw in the return of the Chinese an opportunity to do so. They were in a sense a continuation of the movement for reform that emerged in the 1920s with Tsarong Dzasa as its main proponent but was stopped short by the 13th Dalai Lama under the pressure of conservative clerics and aristocrats.[23]

Implementing the Seventeen Point Agreement (1951–1952)

[edit]Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme was instrumental in solving the food problems of the People's Liberation Army in 1951–1952 by creating a Kashag subcommittee tasked with inventorying grain stores with a view to selling some to the PLA in accordance with point 16 of the Seventeen Point Agreement ("The local government of Tibet will assist the People's Liberation Army in the purchase of food, fodder, and other daily necessities").[24][25]

A Kashag minister trusted by both the Chinese and the Dalai Lama (1953–1954)

[edit]Ngapoi was appointed by the Tibetan government to head the newly formed Reform Assembly. He was the Kashag minister (Kalön) most trusted not only by the Chinese but also by the Dalai Lama. The latter, who was in favour of reforms and modernization, frequently discussed political issues with Ngapoi in private. As a result, in 1953–1954, the Reform Assembly crafted new laws reforming interest rates, old loans, and the administration of counties.[26]

Administrative, military, and legislative responsibilities

[edit]

After 1951, Ngapoi's career continued within the ranks of Chinese Communist administration of Tibet. He served as the leader of the Liberation Committee of Chamdo Prefecture until 1959.[27] He was also a member of the Central People's Government's State Ethnic Affairs Commission and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference National Committee between 1951 and 1954.[6]

He was Deputy Commander of the Tibet Military District between 1952 and 1977, and a member of the National Defence Council from 1954 through the Cultural Revolution. He was appointed as lieutenant general and awarded the "Order of Liberation" first class in 1955.[28]

Secretary General of the Preparatory Committee for the Tibet Autonomous Region

[edit]When in April 1956 a Preparatory Committee for the Establishment of the Autonomous Region of Tibet was set up in accordance with the central government's decision, Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme was appointed its secretary general.[29] He was appointed vice-president of the Committee in 1959, the 10th Panchen Lama being its president.[30]

Chairman of the People's Committee of the Tibet Autonomous Region

[edit]

After his appointment as acting chairman of the Preparatory Committee of the Tibet Autonomous Region in 1964, Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme became the chairman of the People's Committee of the newly established Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) in 1965.[31]

Vice Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress

[edit]He represented Tibet in seven National People's Congresses as a Vice Chairman of the Standing Committee from the 1st National People's Congress in 1954 to the 7th in 1988. He was head of the NPC delegations to Colombia, Guyana, West Indies, Sri Lanka and Nepal in the early 1980s.[6]

In 1999, he became a member of the Preparatory Committee for the Special Administrative Region of Macau.[32]

From 1979 to 1993, he was Chairman of the National People's Congress Ethnic Affairs Committee.[33]

Other roles

[edit]He was an honorary president of the Buddhist Association of China beginning in 1980.[6] He was also an honorary president of the Tibetan Wildlife Protection Association, which was founded in 1991.[34] In April 1992, he became chairman of the newly established Aid Tibet Development Foundation.[35] He was also president of the China Association for the Preservation and Development of Tibetan Culture, which was established on June 21, 2004.[36]

Death

[edit]Ngapoi died at 16:50 on December 23, 2009, from an unspecified illness in Beijing at the age of 99 (or 100 according to East Asia's custom of counting a person's age by starting from 1 at the time of his or her birth). His funeral was held at the Funeral Parlor of the Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery on the morning of December 28.[37]

He was described as "a great patriot, renowned social activist, good son of Tibetan people, outstanding leader of China's ethnic work and close friend of the CPC", by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.[2]

Almost all the top leaders of the Chinese Communist Party turned up to pay him respects at his funeral, including CCP general secretary Hu Jintao, ex-general secretary Jiang Zemin, Wu Bangguo, Wen Jiabao, Jia Qinglin, Li Changchun, Xi Jinping, He Guoqiang, Zhou Yongkang, etc.[38]

The Tibetan government in exile headed by Prof. Samdhong Rinpoche called him an "honest and patriotic" person who made great efforts to preserve and promote the Tibetan language. "He was someone who upheld the spirit of the Tibetan people."[39]

As journalist Kalsang Rinchen observes, both Beijing and Dharamsala appear saddened by the demise of the man who signed the 17-point agreement. "[The] Chinese state run news agency Xinhua hailed him for ushering in 'major milestones in Tibet, such as the democratic reforms and the founding of the Autonomous Regional Government,' while the Tibetan government in exile remembered him for calling on the Central Government in 1991 'to implement articles of the 17-point Agreement in general and specifically those articles which state that Tibet's political status will not be changed'."[40]

A rare comment on Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme can be found in the memoirs of Phuntsok Tashi, a Tibetan who served as an interpreter in the 1951 peace negotiations and signing of the Seventeen Point Agreement: Ngapoi is portrayed as "an honest, clever, intelligent, experienced and far-seeing man."[41]

Depiction

[edit]In the 1997 film Seven Years in Tibet, based on the memoir of the Austrian explorer and mountaineer Heinrich Harrer, Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme is played by the actor BD Wong. In the movie he is depicted as being responsible for destroying a Tibetan ammunition depot, thus sealing the defeat of the Lhasa loyalist army at Chamdo.

Quotations

[edit]

- According to the Tibetan government in exile special envoy Lodi Gyari Rinpoche, he said in 1988: "It is because of the special situation in Tibet that in 1951 the Seventeen Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet, between the central people's government and the local Tibetan government, came about. Such an agreement has never existed between the central government and any other minority region. We have to consider the special situation in Tibetan history while drafting policies for Tibet in order to realise its long-term stability. We must give Tibet more autonomous power than other minority regions. In my view, at present, the Tibet Autonomous Region has less autonomy than other autonomous regions, let alone compared with provinces. Therefore Tibet must have some special treatment and have more autonomy like those special economic zones. We must employ special policies to resolve the special characteristics which have pertained throughout history.".[42] This was translated by Tibet Information Network in 1992 from a 1988 issue of the Bulletin of the History of the Tibet Communist Party.[43]

- According to the secretary of TGE's Department of Information and International Relations Tempa Tsering, he is on record as having said on August 31, 1989, in Tibet Daily, that the claim by the Dalai Lama's envoy "Wu Zhongxin of having presided over the enthronement ceremony (of the 14th Dalai Lama) on the basis of this photograph (of the Chinese official with the young Dalai Lama, supposed to have been taken on this occasion) is a blatant distortion of historical facts.".[44]

Published works

[edit]- Ngapo Ngawang Jigmei et al., Tibet (with a foreword by Harrison Salisbury), Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, or New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1981, 296 p. (a coffee-table book)

- On the 1959 Armed Rebellion, in China Report, 1988, vol. 24, pp. 377–382.

- A great Turn in the Development of Tibetan History, published in the first issue of the China Tibetology quarterly, Beijing, 1991 / Grand tournant historique au Tibet, in La Tibétologie en Chine, n° 1, 1991.

- On Tibetan Issues, Beijing, New Star Publishers, 1991.

- Narrator in Masters of the Roof of the Wind, a documentary on feudalism in old Tibet[45]

- Ngapoi recalls the founding of the TAR, an interview published by Chinaview, on August 30, 2005.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Ngapoi's daughter was the mother of the 3rd Jamgön Kongtrül, an important reincarnate lama.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Powers, John (2016). "Appendix B – p. 11)". The Buddha Party: How the People's Republic of China Works to Define and Control Tibetan BuddhismOxford University Press. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0199358151.

- ^ a b "Senior Chinese legislator, political advisor passes away". Xinhua. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ^ Tsering Shakya (1999). The Dragon in the Land of Snows. A History of Modern Tibet Since 1947. Columbia University Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780231118149.

He was the illegitimate son of a nun from one of the leading aristocratic families of Tibet, Horkhang, who had acquired the surname of Ngabo by marrying a young widow of Ngabo Shape.

- ^ Jacques de Goldfiem, Personnalités chinoises d'aujourd'hui, Éditions L'Harmattan, 1989, pp. 189–190.

- ^ a b Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme 1910–2009 Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine, Tibet Sun, 23 December 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Mackerras, Colin. Yorke, Amanda. The Cambridge Handbook of Contemporary China. (1991). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38755-8. p. 100.

- ^ a b Bhuchung D. Sonam, Ngabo — Yes Tibetan, No Patriot Archived 2011-07-15 at the Wayback Machine, Phayul.com, December 26, 2009.

- ^ Puncog Zhaxi, La libération pacifique du Tibet comme je l'ai vécue, in Jianguo Li (ed.), Cent ans de témoignages sur le Tibet: reportages de témoins de l'histoire du Tibet, 2005, 196 p., pp. 72–82, esp. p. 72: "[...] il a conclu que les troupes tibétaines étaient incapables de faire front à l'APL (l'Armée populaire de libération) qui [...] avait libéré l'ensemble du pays en triomphant de millions de militaires du Kuomintang."

- ^ Gary Wilson, It was no Shangri-La: Hollywood Hides Tibet's True History Archived 2009-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, in Workers World Newspaper, December 4, 1997.

- ^ Ngapoi recalls the founding of the TAR www.chinaview.cn, 2005-08-30.

- ^ "Tibet: Proving Truth From Facts, The Invasion and Illegal Annexation of Tibet". Archived from the original on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C., A History of Modern Tibet – The Demise of the Lamaist State: 1912–1951, 1989, p. 813.

- ^ Tsering, Shakya (1999). The Dragon in the Land of Snows. A History of Modern Tibet Since 1947. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-7126-6533-9, pp. 70–71.

- ^ According to Dalai Lama's My Land and My People, (New York: 1992), p. 95, acting Tibetan Prime Minister Lukhangwa said: "It was absurd to refer to the terms of the Seventeen-Point Agreement. Our people did not accept the agreement and the Chinese themselves had repeatedly broken the terms of it. Their army was still in occupation of eastern Tibet; the area had not been returned to the government of Tibet, as it should have been."

- ^ a b Goldstein, Melvyn C., A History of Modern Tibet – The Calm before the Storm: 1951–1959, 2007, p. 87, p. 96 n 32.

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C., A History of Modern Tibet – The Demise of the Lamaist State: 1912–1951, 1989, pp. 758–759.

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C., A History of Modern Tibet – The Calm before the Storm: 1951–1959, 2007, pp. 87, 95–98.

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C., A History of Modern Tibet – The Calm before the Storm: 1951–1959, 2007, pp96–97.

- ^ Gyatso, Tenzin, Dalai Lama XIV, interview with Grunfeld, A. Tom, 25 July 1981. see Grunfeld's The Making of Modern Tibet, chapter 6, note 22.

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C., A History of Modern Tibet – The Demise of the Lamaist State: 1912–1951, 1989, pp 812–813.

- ^ The History of Tibet: Volume III The Modern Period: 1895-1959, edited by Alex McKay, London and New York: Routledge Curzon (2003), p. 603.

- ^ "The 17-Point Agreement" The full story as revealed by the Tibetans and Chinese who were involved Archived 2008-05-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Melvyn C. Goldstein,, A History of Modern Tibet – The Calm before the Storm: 1951–1959, University of California Press, 2007, p. 87, p. 191: "(...) there were a few others who had very modern and progressive ideas. In particular, a small number of elite Tibetans genuinely favored working closely with the Chinese to implement the agreement and modernize Tibet. (...) They were, in a sense, a continuation of a movement for reform and change that began after (...) 1914, when a group of young aristocratic officers led by Tsarong (...) sought to create a modern and effective army. They had been thwarted by clerics and conservative aristocrats who (in the middle 1920s) persuaded the 13th Dalai Lama that they were a threat to his rule and to religion."

- ^ Melvyn C. Goldstein, The Snow Lion and the Dragon, online version: "The dire food problems of the Chinese led Ngabö to push successfully for one interesting innovation in Lhasa – the creation of a subcommittee of the Kashag whose mission was to deal effectively with matters concerning the arrangements and accommodations of the Chinese, including food for the PLA."

- ^ Melvyn C. Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet, vol. 2: The Calm Before the Storm: 1951–1955, Asian Studies Series, University of California Press, 2007, p. 639: "Point 16 (...) stated, 'The local government of Tibet will assist the People's Liberation Army in the purchase and transport of food, fodder, and other daily necessities'."

- ^ Melvyn C. Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet, vol. 2, The Calm before the Storm: 1951-1955, op. cit., chap. 22, p. 547: "On the Tibetan government's side, a reform organization headed by Ngabo was begun. He was not only the Kashag minister most trusted by the Chinese but also the one most trusted by the Dalai Lama, who frequently discussed political issues with him privately and who himself was in favour of reforms and modernization for Tibet. In 1953-1954, therefore, the Tibetan government's Reform Assembly crafted new laws reforming interest rates, old loans, and the administration of counties."

- ^ "Who's Who in China's Leadership". China Internet Information Center..

- ^ Lieutenant General - Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme, www.mod.gov.cn, August 1, 2009.

- ^ White Paper 1998: New Progress in Human Rights in the Tibet Autonomous Region Archived 2011-06-14 at the Wayback Machine, February 1998, Permanent Mission of the People's Republic of China to the UN.

- ^ Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme passes away at 100 Archived 2011-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, www.chinaview.cn, 23 December 2009 : "1959-1964: Vice-chairman of CPPCC National Committee, vice-chairman of Preparatory Committee of Tibet Autonomous Region, and member of National Defense Council."

- ^ Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme passes away at 100 Archived 2011-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, op. cit. : "1964-1965: [...] acting chairman of (the) Preparatory Committee of (the) Tibet Autonomous Region" - "1965-1979: [...] chairman of People's Committee of Tibet Autonomous Region"

- ^ Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme, China Vitae.

- ^ Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme passes away at 100 Archived 2011-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, op. cit. : "1979-1981: [...] chairman of (the) NPC Ethnic Affairs Committee [...], 1981-1983: [...] chairman of (the) NPC Ethnic Affairs Committee [...], 1983-1993: [...] chairman of (the) NPC Ethnic Affairs Committee."

- ^ Himalayan Waves Trekking Archived 2009-06-14 at the Wayback Machine, Flora and fauna: "The Tibetan Wildlife Protection Association was established in 1991, with Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme as its honorary president."

- ^ 《中华人民共和国日史》 编委会 (2003). 中华人民共和国日史. 中华人民共和国日史 (in Chinese). 四川人民出版社. p. 159. ISBN 978-7-220-06468-5. Retrieved 2024-08-24.

- ^ Body of senior Chinese legislator, political advisor cremated in Beijing Archived 2012-11-04 at the Wayback Machine, China View, December 28, 2009: "He was also president of the China Association for Preservation and Development of Tibetan Culture."

- ^ Funeral for Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme held in Beijing, China Tibet Online, December 29, 2009: "Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme's funeral was held at Beijing's Babaoshan Funeral Parlor on the morning of December 28."

- ^ Body of senior Chinese legislator, political advisor cremated in Beijing Archived 2012-11-04 at the Wayback Machine, China View, December 28, 2009.

- ^ Kalsang Rinchen, United by Ngabo's death, Dharamsala and Beijing mourns Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, December 25, 2009 (reprinted from Phayul).

- ^ United by Ngabo's death, Dharamsala and Beijing mourns, op. cit.

- ^ Puncog Zhaxi, La libération pacifique du Tibet comme je l'ai vécue, op. cit., p. 72: "un homme honnête, habile, intelligent, expérimenté et clairvoyant."

- ^ Lodi Gyari, 'Seeking unity through equality', Himal, January 26, 2007, reproduced in www.phayul.com.

- ^ When did Tibet come within the sovereignty of China?, by Apei Awang Jinmei (Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme), History of the Tibet Communist Party, Volume 3, 1988 (General Series No. 21), published in translation in Background Papers on Tibet, Tibet Information Network, London; 1992.

- ^ Tempa Tsering, China's highest Tibetan official excluded from selection meeting Archived 2008-05-21 at the Wayback Machine, www.tibet.com, 10 November 1995: "Official communist Chinese documents and media report that the envoy of the nationalist Chinese, Wu Zhongxin, gave the official Kuomintang recognition of the 14th Dalai Lama in 1940 and had presided over his enthronement, and to support this claim re-produced a photograph of the Chinese official with the young Dalai Lama, saying that this was taken during the enthronement ceremony. But Ngapo is on record saying that this photograph was taken a few days after the ceremony when Wu had the privilege of having a private audience with His Holiness the Dalai Lama."

- ^ Films and videos in Tibet Archived 2010-12-09 at the Wayback Machine, maintained by A. Tom Grunfeld.

Sources

[edit]- Tsering, Shakya (1999). The Dragon in the Land of Snows. A History of Modern Tibet Since 1947. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-7126-6533-9.

- Melvyn Goldstein (2007). A History of Modern Tibet, Volume 2: The Calm Before the Storm: 1951–1955, University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24941-7.

- Anna Louise Strong (1959). Tibetan Interviews, Peking: New World Press (contains Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme's account of the Chamdo battle and his conversations with the author)

- Puncog Zhaxi (Phuntsok Tashi) (2005). La libération pacifique du Tibet comme je l'ai vécue, in Jianguo Li (ed.), Cent ans de témoignages sur le Tibet: reportages de témoins de l'histoire du Tibet, 196 p.

- Li Jianxiong (April 2004). Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme, China Tibetology Publishing House

- Powers, John (2017). The Buddha Party: How the People's Republic of China Works to Define and Control Tibetan Buddhism, Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199358151.

External links

[edit]- "Ngapo Ngawang Jigme - a profile". Archived from the original on 2010-11-28. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- "Ngabo – Yes Tibetan, No Patriot". Archived from the original on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- "Official biography on 'Who's who in China's Leadership'". Retrieved 2010-01-07.

- "World Tibet Network News. Monday, October 16, 2000: 'Nothing Will Change': Tibetan "traitor" Ngabo Ngawang Jigme (Asiaweek)". Retrieved 2007-07-08.[permanent dead link]

- "World Tibet Network News. Thursday, April 9, 1998: China's top Tibetan official criticises Panchen Lama report (TIN)". Retrieved 2007-07-08.[permanent dead link]

- Cao, Chang-ching (25 April 2001). "Tibetan tragedy began with a farce. Taipei Times, Wednesday, April 25, 2001". Retrieved 2007-07-08.

- "Interview with Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme", South China Morning Post, 4 April 1998 Hosted by the Canada Tibet Committee

- Ngapoi recalls the founding of the TAR, www.chinaview.cn, 2005-08-30

- Group of photos of Ngapoi Ngawang Jigmei, Tibet328.cn, 12-25-2009

- Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme's life in pictures, China Tibetology Network site