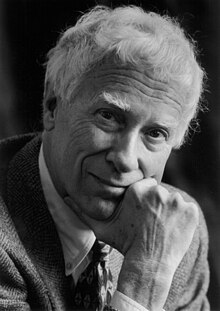

Nicholas Wolterstorff | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Nicholas Paul Wolterstorff January 21, 1932 |

| Spouse |

Claire Wolterstorff (m. 1955) |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | |

| Thesis | Whitehead's Theory of Individuals (1956) |

| Academic advisors | Donald Cary Williams[1] |

| Influences | |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | |

| Sub-discipline | |

| School or tradition | |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral students | Phillip Cary |

| Notable ideas | Reformed epistemology |

| Influenced | |

Nicholas Paul Wolterstorff (born January 21, 1932) is an American philosopher and theologian. He is currently Noah Porter Professor Emeritus of Philosophical Theology at Yale University.[2] A prolific writer with wide-ranging philosophical and theological interests, he has written books on aesthetics, epistemology, political philosophy, philosophy of religion, metaphysics, and philosophy of education. In Faith and Rationality, Wolterstorff, Alvin Plantinga, and William Alston developed and expanded upon a view of religious epistemology that has come to be known as Reformed epistemology.[3] He also helped to establish the journal Faith and Philosophy and the Society of Christian Philosophers.

Biography

[edit]Wolterstorff was born on January 21, 1932,[4] to Dutch emigrants in a small farming community in southwest Minnesota.[5][6] After earning his BA in philosophy at Calvin College, Grand Rapids, Michigan, in 1953, he entered Harvard University, where he earned his MA and PhD in philosophy, completing his studies in 1956. He then spent a year at the University of Cambridge, where he met C. D. Broad. From 1957 to 1959, he was an instructor in philosophy at Yale University. Then he took the post of Professor of Philosophy at Calvin College and taught for 30 years.[5] He is now teaching at Yale as Noah Porter Professor Emeritus Philosophical Theology.

In 1987 Wolterstorff published Lament for a Son after the untimely death of his 25-year-old son Eric in a mountain climbing accident. In a series of short essays, Wolterstorff recounts how he drew on his Christian faith to cope with his grief. Wolterstorff explained that he published the book "in the hope that it will be of help to some of those who find themselves with us in the company of mourners."[7]

He has been a visiting professor at Harvard University, Princeton University, Yale University, the University of Oxford, the University of Notre Dame, the University of Texas, the University of Michigan, Temple University, the Free University of Amsterdam (Vrije Universiteit), and the University of Virginia. In 2007, he received an honorary Doctorate in Philosophy from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.[8] He has been retired since June 2002.

Wolterstorff published his memoir with William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. in 2019, illustrating the close relationship between his personal life and his distinguished academic career.[9]

Professional distinctions

[edit]- Woodrow Wilson Fellowship, 1953

- Harvard Foundation Fellowship, 1954

- Josiah Royce Memorial Fellowship, Harvard University, 1954

- Fulbright Scholarship, 1957

- President of the American Philosophical Association (Central Division)

- President of the Society of Christian Philosophers[2]

- Senior Fellow, Institute for Advanced Study in Culture, University of Virginia, 2005

Endowed lectureships

[edit]

- Kuyper Lectures, Free University of Amsterdam, 1981

- Wilde Lectures, University of Oxford, 1993

- Gifford Lectures: "Thomas Reid and the Story of Epistemology", St Andrews University, 1995

- Tate-Willson Lectures, Southern Methodist University, 1991

- Stone Lectures, Princeton Theological Seminary, 1998

- Lectures at Southern Seminary, Lecture #2, Lecture #3, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2000

- Taylor Lectures, Yale University, 2001

- Laing Lectures, Regent College, 2007

Personal life

[edit]This section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources. (August 2024) |

Nicholas Wolterstorff lives in Grand Rapids, Michigan, with his wife Claire. He has four grown children. His oldest son died in a mountain climbing accident at age 25. He has seven grandchildren.

Thought

[edit]This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

While an undergraduate at Calvin College, Wolterstorff was greatly influenced by professors William Harry Jellema, Henry Stob, and Henry Zylstra, who introduced him to schools of thought that have dominated his mature thinking: Reformed theology and common sense philosophy. (These have also influenced the thinking of his friend and colleague Alvin Plantinga, another alumnus of Calvin College).

Wolterstorff builds upon the ideas of the Scottish common-sense philosopher Thomas Reid, who approached knowledge "from the bottom-up". Instead of reasoning about transcendental conditions of knowledge, Wolterstorff suggests that knowledge and our knowing faculties are not the subject of our research but have to be seen as its starting point. He rejects classical foundationalism and instead sees knowledge as based upon insights in reality which are direct and indubitable.[5] In Justice in Love, he rejects fundamentist notions of Christianity that hold to the necessity of the penal substitutionary atonement and justification by faith alone.

Bibliography

[edit]Selected writings

[edit]- On Universals: An Essay in Ontology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1970.

- Reason within the Bounds of Religion. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 1976. 2nd ed. 1984

- Works and Worlds of Art. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1980.

- Art in Action: Toward a Christian Aesthetic. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 1980. 2nd ed. 1995

- Educating for Responsible Action. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 1980.

- Until Justice and Peace Embrace. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. 1983. 2nd ed. 1994.

- Faith and Rationality: Reason and Belief in God (ed. with Alvin Plantinga). Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. 1984.

- Lament for a Son. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 1987.

- "Suffering Love" in Philosophy and the Christian Faith (ed.Thomas V. Morris). Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. 1988.

- Divine Discourse: Philosophical Reflections on the Claim That God Speaks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1995.

- John Locke and the Ethics of Belief. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1996.

- Religion in the Public Square (with Robert Audi). Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield. 1997.

- Thomas Reid and the Story of Epistemology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2001.

- Educating for Life: Reflections on Christian Teaching and Learning. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. 2002.

- "An Engagement with Rorty" in The Journal of Religious Ethics, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Spring, 2003), pp. 129–139.

- Educating for Shalom: Essays on Christian Higher Education. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2004.

- Justice: Rights and Wrongs. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 2008.

- Inquiring about God: Selected Essays, Volume I (ed. Terence Cuneo). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2009.

- Practices of Belief: Selected Essays, Volume II (ed. Terence Cuneo). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2009.

- Hearing the Call: Liturgy, Justice, Church, and World . William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2011.

- The Mighty and the Almighty: An Essay in Political Theology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2012.

- Journey toward Justice: Personal Encounters in the Global South. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. 2013.

- Understanding Liberal Democracy: Essays in Political Philosophy (ed. Terence Cuneo). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2012.

- Art Rethought: The Social Practices of Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2015.

- Justice in Love. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2015.

- The God We Worship: An Exploration of Liturgical Theology. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2015.

- Acting Liturgically: Philosophical Reflections on Religious Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2018. ISBN 9780198805380

- In This World of Wonders: Memoir of a Life in Learning. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2019.

- United in Love: Essays on Justice, Art, and Liturgy. (ed. Joshua Cockayne and Jonathan Rutledge). Eugene, OR: Cascade, Wipf & Stock. 2021 ISBN 9781666715590

Secondary

[edit]- Sloane, Andrew, On Being A Christian in the Academy: Nicholas Wolterstorff and the Practice of Christian Scholarship, Paternoster, Carlisle UK, 2003.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wolterstorff, Nicholas (November 2007). "A Life in Philosophy". Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association. 81 (2): 93–106. JSTOR 27653995.

- ^ a b "Nicholas Wolterstorff". religiousstudies.yale.edu. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ Forrest, Peter (2017). "The Epistemology of Religion". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2017 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ "CV:Nicholas Paul Wolterstorff" (PDF). s3.amazonaws.com.

- ^ a b c "Nicholas Wolterstorff". The Gifford Lectures. August 18, 2014. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ "6 Questions with Nicholas Wolterstorff". EerdWord (publisher blog). January 18, 2019. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ "Lament for a Son". Eerdmans. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- ^ "Honorary doctorates", Top researchers, NL: VU.

- ^ "In This World of Wonders". Eerdmans. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

External links

[edit]- Faculty page at Yale

- Interview from The Christian Century.

- "The Irony of It All"[permanent dead link] in The Hedgehog Review vol. 9, no. 3 (Fall 2007). Article discussing human dignity and justice.

- Lecture at Calvin College on "How Calvin Fathered a Renaissance in Christian Philosophy".

- Wolterstorff's Spiritual Autobiography from Clark, Kelly James, Philosophers Who Believe (Intervarsity Press, 1993).

- Theology and Ethics Contains many PDF files of Wolterstorff's work not available elsewhere.

- Art in Action: New Thoughts Lecture at the 2009 International Arts Movement.

- Lectures by Wolterstorff from the C.S. Lewis Institute.

- Faith and Philosophy

- Society of Christian Philosophers