| Nick Carraway | |

|---|---|

| The Great Gatsby character | |

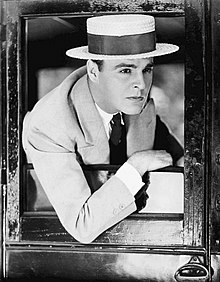

Nick Carraway as portrayed by actor Neil Hamilton in The Great Gatsby (1926) | |

| First appearance | The Great Gatsby (1925) |

| Created by | F. Scott Fitzgerald |

| Portrayed by | See list |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Bond salesman |

| Relatives | Daisy Buchanan (cousin) |

| Origin | American Midwest |

| Nationality | American |

Nick Carraway is a fictional character and narrator in F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1925 novel The Great Gatsby. The character is a Yale University alumnus from the American Midwest, a World War I veteran, and a newly arrived resident of West Egg on Long Island, near New York City. He is a bond salesman and the neighbor of enigmatic millionaire Jay Gatsby. He facilitates a sexual affair between Gatsby and Nick's second cousin, once removed, Daisy Buchanan which becomes one of the novel's central conflicts. Carraway is easy-going and optimistic, although this latter quality fades as the novel progresses. After witnessing the callous indifference and insouciant hedonism of the idle rich during the riotous Jazz Age, he ultimately chooses to leave the eastern United States forever and returns to the Midwest.[1]

The character of Nick Carraway has been analyzed by scholars for nearly a century and has given rise to a number of critical interpretations. According to scholarly consensus, Carraway embodies the pastoral idealism of Fitzgerald.[2] Fitzgerald identifies the Midwest—those "towns beyond the Ohio"—with the perceived virtuousness and rustic simplicity of the American West and as culturally distinct from the decadent values of the eastern United States.[2] Carraway's decision to leave the East evinces a tension between a complex pastoral ideal of a bygone America and the societal transformations caused by industrialization.[3] In this context, Nick's repudiation of the East represents a futile attempt to withdraw into nature.[4] Yet, as Fitzgerald's work shows, any technological demarcation between the eastern and western United States has vanished,[5] and one cannot escape into a pastoral past.[4]

Since the 1970s, scholarship has often focused on Carraway's sexuality.[6][7] In one instance in the novel, Carraway departs an orgy with a feminine man and—following suggestive ellipses—next finds himself standing beside a bed while the man sits between the sheets clad only in his underwear.[8] Such passages have led scholars to describe Nick as possessing a queerness and prompted analyses about his attachment to Gatsby.[9] For these reasons, the novel has been described as an exploration of sexual identity during a historical era typified by the societal transition towards modernity.[10][11]

The character has appeared in various media related to the novel, including stage plays, radio shows, television episodes, and feature films. Actor Ned Wever originated the role of Nick on the stage when he starred in the 1926 Broadway adaptation of Fitzgerald's novel at the Ambassador Theatre in New York City.[12] That same year, screen actor Neil Hamilton played the role in the now lost 1926 silent film adaptation.[13] In subsequent decades, the role has been played by many actors including Macdonald Carey, Lee Bowman, Rod Taylor, Sam Waterston, Paul Rudd, Bryan Dick, Tobey Maguire and others.

Inspiration for the character

[edit]Fitzgerald based the character of Nick Carraway largely upon himself. The author was a young Midwesterner from Minnesota. Like Carraway who went to Yale, Fitzgerald attended Princeton, an Ivy League school.[15] Whereas Nick's father owns a hardware store,[16] Fitzgerald's father owned a furniture store in Minnesota until 1898.[17] Many scholars, including Fitzgerald's close friend Edmund Wilson, posit that Fitzgerald created the character of Nick as an ideal version of himself.[18] His "characters—and himself—are actors in an elfin harlequinade".[18]

Nick's Midwestern viewpoint reflects Fitzgerald's experience. According to his friend Edmund Wilson, Fitzgerald was "as much of the Middle West of large cities and country clubs" as writer Sinclair Lewis was "of the Middle West of the prairies and little towns".[19] Wilson ascribed to Fitzgerald many of the strengths and weaknesses typical of 1920s Midwesterners including a "sensitivity and eagerness for life without a sound base of culture and taste".[19]

Wilson posited that Fitzgerald's Midwestern identity informed much of Carraway's perceptions; in particular, when Fitzgerald "approaches the East, he brings to it the standards of the wealthy West—the preoccupation with display, the love of magnificence and jazz, the vigorous social atmosphere of amiable flappers and youths comparatively unpoisoned as yet by the snobbery of the East".[20]

When creating the literary character of Carraway, Fitzgerald originally named the character Dud.[21] In earlier drafts of the novel,[a] the character had a previous romance with Daisy Buchanan prior to their reunion on Long Island.[23] Fitzgerald's later rewrites excised any romantic past between Nick and Daisy, as well as added and then deleted a passage implying that Nick departed a job after a male acquaintance amorously pursued him.[24][25] He also changed the viewpoint of an omniscient narrator to Nick's subjective perspective.[25][26] These alterations introduced considerable ambiguity regarding both Nick's reliability as a narrator and his sexuality which became the focus of later scholarship.[26][27]

The ambiguity of Nick's sexuality reflects a similar ambiguity regarding Fitzgerald's own sexuality. During his lifetime, Fitzgerald's sexuality became a subject of debate among his friends and acquaintances.[28][29][30] As a youth, Fitzgerald had a close relationship with Father Sigourney Fay,[31] a possibly gay Catholic priest,[32][33] and Fitzgerald later used his last name for the idealized romantic character of Daisy Fay.[34] After college, Fitzgerald cross-dressed during outings in Minnesota, and he flirted with other men at social events.[14][35]

I don't know what it is in me or that comes to me when I start to write. I am half feminine—at least my mind is...

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, Letter to Laura Guthrie, 1935[36]

Years later, while drafting The Great Gatsby, rumors dogged Fitzgerald among the American expat community in Paris that he was gay.[29] Soon after, Fitzgerald's wife Zelda Sayre likewise doubted his heterosexuality and asserted that he was a closeted homosexual.[37] She belittled him with homophobic slurs,[38] and she alleged that Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway engaged in sexual relations.[39][40] These incidents strained the Fitzgeralds' marriage at the time of the novel's publication.[37]

Although Fitzgerald's sexuality remains a subject of scholarly debate,[b] such biographical details lent credence to interpretations by literary scholars that his fictional characters such as Nick Carraway, Jordan Baker and others are either gay or bisexual surrogates.[43] Scholars have particularly focused on Fitzgerald's statement in a 1935 letter to acquaintance Laura Guthrie that his mind was "half feminine".[44] Although born "masculine,"[45] Fitzgerald nonetheless stated that he was "half feminine—at least my mind is... Even my feminine characters are feminine Scott Fitzgeralds."[44][46][47]

Fictional character biography

[edit]In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I've been turning over in my mind ever since. "Whenever you feel like criticising any one," he told me, "just remember that all the people in this world haven't had the advantages that you've had."

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chapter I, The Great Gatsby[48]

In his narration, Nick Carraway explains that he was born in the Midwestern United States, a region which he describes as "the ragged edge of the universe".[16] The Carraway family had a tradition that they're descended from the Dukes of Buccleuch but rather owned a hardware business since 1851 and have been a prominent, well-to-do family for generations.[16] Due to his privileged upbringing, Carraway's father cautioned him against passing judgment on individuals who did not enjoy the same advantages.[48] After his matriculation from Yale University in 1915 and the U.S. entry into World War I in 1917, Nick served in the Ninth Machine-Gun Battalion of the 3rd Division.[c][51][52]

After the Allied Powers signed an armistice with Imperial Germany in 1918, a restless Nick moved from the Midwest to West Egg, a wealthy enclave on Long Island, to learn about the bond business.[d] He lives across the bay from his affluent second cousin, once removed, Daisy Buchanan and her husband Tom Buchanan, formerly Nick's classmate at Yale. They introduce him to their cynical friend Jordan Baker, a masculine golf champion and heiress.[56] Jordan and Nick embark upon an exploratory romance, although Carraway describes his interest in Jordan Baker as not love but "a sort of tender curiosity".[57]

Soon after, Nick's wealthy neighbor Jay Gatsby invites him to one of his lavish soirées, replete with famous guests and hot jazz music. Nick is intrigued by the enigmatic millionaire, especially when Gatsby introduces him to Meyer Wolfsheim, a Jewish gangster who is rumored to have been behind the Black Sox Scandal, the fixing the World Series in 1919 and helped Gatsby make his fortune in the bootlegging business.[58][59] Gatsby confesses to Nick that he has been in love with Daisy since the war and that his extravagant lifestyle is an attempt to win her affections. He asks Nick for his help in seducing her and Nick invites Daisy over to his house without telling her that Gatsby will be there.[60] When Gatsby and Daisy resume their love affair, Nick serves as their confidant.

When I came back from the East last autumn I felt that I wanted the world to be in uniform and at a sort of moral attention forever; I wanted no more riotous excursions with privileged glimpses into the human heart.

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chapter I, The Great Gatsby[61]

Several months later, Tom discovers the affair when Daisy addresses Gatsby with unabashed intimacy in front of him. After a confrontation at the Plaza Hotel in New York City, Gatsby and Daisy leave together in his car. Nick later learns that Daisy struck and killed George's wife and Tom's lover, Myrtle Wilson, in Gatsby's car. Tom informs George that Gatsby had been driving the car. George kills Gatsby and then himself. Nick holds a funeral for Gatsby and breaks up with Jordan.[62]

Nick now loathes New York City and decides that Gatsby, Daisy, Tom and he were all Midwesterners unsuited to Eastern life.[63] Nick encounters Tom and initially refuses to shake his hand. Tom admits he told George that Gatsby owned the vehicle that killed Myrtle. Before returning to the Midwest, Nick returns to Gatsby's mansion and stares across the bay at the green light emanating from the end of Daisy's dock.[64]

Critical analysis

[edit]Unreliable narrator

[edit]Every one suspects himself of at least one of the cardinal virtues, and this is mine: I am one of the few honest people that I have ever known.

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chapter III, The Great Gatsby[65]

Since the 1960s, critics have drawn attention to Nick Carraway's status as first an observer and then as a participant, questioning his reliability as narrator.[66][26] As the narrator of the story, other characters are presented as Carraway perceives them, and he directs the reader's sympathies.[67]

In 1966, critic Gary Scrimgeour argued in Criticism magazine that the narrator's unreliability perhaps indicated Fitzgerald's confusion about the novel's plot, while critic Charles Wild Walcutt posited in the same year that Nick's narrative unreliability is intentional, and critic Thomas Boyle argued in 1969 that Nick's unreliability is an integral part of the novel.[66][66]

Although Carraway proclaims himself to be "one of the few honest people that I have ever known," critics observe that he is shallow, confused, hypocritical, and immoral.[65][66][60] He says little about a previous marital engagement and his wartime experience; both of which are first raised by other characters.[68][69]

Lost Generation

[edit]

Despite the fact that F. Scott Fitzgerald rejected Gertrude Stein's characterization of World War I veterans as a so-called "lost generation" set adrift by the horrors of the conflict,[70][71][72] a number of scholars nonetheless posited that the character of Nick Carraway typifies the disillusioned Lost Generation.[73] In 1944, nearly twenty years after the publication of The Great Gatsby, critic Charles Weir, Jr. speculated that Fitzgerald—who never fought in World War I and did not believe "the war left any real lasting effect"[74][72]—was nevertheless a member of Stein's war-shattered "Lost Generation".[75] Weir argued that all of Fitzgerald's literary themes must be understood in the context of the conflict "leaving behind it a generation of sad young men, distrustful of ideas or of ideals, shunning any sort of generalization, 'cynical rather than revolutionary,' 'tired of Great Causes.'"[75]

In 1952, almost a decade after Weir's article, scholar Edwin S. Fussell similarly contended that Fitzgerald was a forlorn member of the Lost Generation.[76] However, Fussell argued that The Great Gatsby functioned as a critique of the Lost Generation.[76] He wrote that Fitzgerald's "greatest discovery" was "that there was nothing new about the Lost Generation except its particular symbols."[76] Fussell contended that the novel criticized the cynical attitude of the Lost Generation and amounted to an ironic rejection of this generation and its beliefs in favor of a "romantic wonder that is extensive enough to comprehend all American experience."[76]

Following the work of Weir and Fussell, later scholars such as Jeffrey Steinbrink observed that characters such as Nick Carraway typify the Lost Generation.[77] In particular, Carraway reflects the Lost Generation's view of pre-war America as "not simply remote, but archaic, the repository of an innocence long since dead. Possessed of what seemed an irrelevant past, Americans faced an inaccessible future; for a moment in our history there was only the present."[77] Steinbrink speculated that Carraway's journey eastward is "not simply to learn the bond business, but because his wartime experiences have left him restless in his midwestern hometown and because he wishes to make a clean break" from past traumas.[78]

I am tired, too, of hearing that the world war broke down the moral barriers of the younger generation. Indeed, except for leaving its touch of destruction here and there, I do not think the war left any real lasting effect. Why, it is almost forgotten right now. The younger generation has been changing all through the last twenty years. The war had little or nothing to do with it.... Young people, here and in England, have made radical departures from the Victorian era.

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, Shadowland interview, 1921[79]

Although scholars such as Weir, Fussell, Steinbrink, and others attributed the disillusionment of young Americans and the advent of the Jazz Age to the carnage of World War I, Fitzgerald adamantly rejected such theories during his lifetime.[70][71][72] Fitzgerald publicly dismissed Gertrude Stein's view that the veterans were a "lost generation" and expressed confidence in their resilience and fortitude.[70][71]

Fitzgerald believed that the generation that embodied the Jazz Age's cynical hedonism wasn't the veterans but their younger peers who had been adolescents during the war.[80][81][82] These younger persons became the hedonistic luminaries of the era, and older generations merely imitated their wild behavior.[80][83][82] "The generation which had been adolescent during the confusion of the War, brusquely shouldered my contemporaries out of the way," Fitzgerald explained. "This was the generation whose girls dramatized themselves as flappers".[e][88]

Scarcely had the staider citizens of the republic caught their breaths when the wildest of all generations, the generation which had been adolescent during the confusion of the War, brusquely shouldered my contemporaries out of the way and danced into the limelight. This was the generation whose girls dramatized themselves as flappers, the generation that corrupted its elders and eventually overreached itself less through lack of morals than through lack of taste.

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, "Echoes of the Jazz Age", 1931[89]

Declaring that "the war had little or nothing to do" with the change in morals among young Americans or the emergence of the Jazz Age,[79][90] Fitzgerald attributed the sexual revolution among young Americans to a combination of popular literary works by H. G. Wells and other intellectuals criticizing repressive social norms, Sigmund Freud's sexual theories gaining salience, and the invention of the automobile allowing youths to escape parental surveillance in order to engage in premarital sex.[91][79]

Fitzgerald further argued that young Americans became disillusioned after witnessing how police treated peaceful veterans returning from World War I.[92] He claimed that the excessive use of force by police against war veterans during the 1919 May Day Riots triggered a wave of cynicism among young Americans who questioned whether the United States was any better than despotic regimes in Europe.[92][93]

Because of this growing cynicism among American youth, Fitzgerald claimed that the defining characteristic of young Americans during the Jazz Age was political apathy.[94] Critic Edmund Wilson opined that these young Americans regarded civilization as "a contemptible farce of the futile and the absurd; the world of finance, the army, and finally, the world of business are successively and casually exposed as completely without dignity or point. The inference is that, in such a civilization, the sanest and most creditable thing is to forget organized society and live for the jazz of the moment."[95]

Pastoral idealism

[edit]

Throughout the novel, Carraway identifies the Midwest—those "towns beyond the Ohio"—with the perceived virtuousness and rustic simplicity of the American West and as culturally distinct from the decadence of the eastern United States.[2][96] Fitzgerald biographer Andrew Turnbull notes that "in those days the contrasts between East and West, between city and country, between prep school and high school were more marked than they are now, and correspondingly the nuances of dress and manners were more noticeable".[5]

At the end of the novel, Nick ultimately returns to the Midwest after despairing of the decadence and indifference of the East.[97][98] Scholar Thomas Hanzo posits that Carraway must return "to the comparatively rigid morality of his ancestral West and to its embodiment in the manners of Western society. He alone of all the Westerners can return, since the others have suffered, apparently beyond any conceivable redemption, a moral degeneration brought on by their meeting with that form of Eastern society which developed during the Twenties."[99]

Similarly, scholar Jeffrey Steinbrink argues that "the Twenties was both a birth-cry and a death-rattle for, if it announced the arrival of the first generation of modern Americans, it also declared an end to the Jeffersonian dream of simple agrarian virtue as the standard of national conduct and the epitome of national aspiration. The new generation forfeited its claim to the melioristic certainties of an earlier time as the price of its full participation in the twentieth century".[100]

I see now that this has been a story of the West, after all — Tom and Gatsby, Daisy and Jordan and I, we're all Westerners, and perhaps we possessed some deficiency in common which made us subtly unadaptable to Eastern life.

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chapter IX, The Great Gatsby[63]

In 1964, historian and literary critic Leo Marx argued in The Machine in the Garden that Nick Carraway's decision to return to the Midwest in the novel evinces a tension between a complex pastoral ideal of a bygone America and the societal transformations caused by industrialization and machine technology.[3]

Marx argues that Fitzgerald, via Nick Carraway, expresses a pastoral longing typical of other 1920s American writers like William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway.[101] Although such writers cherish the pastoral ideal, they accept that technological progress has deprived this ideal of nearly all meaning.[4] In this context, Nick's repudiation of the eastern United States represents a futile attempt to withdraw into nature.[4] Yet, as Fitzgerald's work shows, any technological demarcation between the eastern and western United States has long since vanished,[5] and one cannot escape into a pastoral past.[4]

Queer reading

[edit]"Keep your hands off the lever," snapped the elevator boy.

"I beg your pardon," said Mr. McKee with dignity, "I didn't know I was touching it."

"All right," I agreed, "I'll be glad to."

. . . I was standing beside his bed and he was sitting up between the sheets, clad in his underwear, with a great portfolio in his hands.

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chapter II, The Great Gatsby[102]

As early as 1945, literary critics such as Lionel Trilling noted that various characters in The Great Gatsby were intended by Fitzgerald to be "vaguely homosexual" and in 1960, writer Otto Friedrich commented upon the ease of examining Nick Carraway's thwarted relations through a queer lens.[103][104][105]

By the 1970s, scholarship increasingly focused on Carraway's sexuality.[6][7] Scholars focus on a passage in which Carraway departs an orgy with a feminine man and—following discussion about an elevator lever and suggestive ellipses—next finds himself standing beside a bed while the man sits between the sheets clad only in his underwear.[106] Such passages have led scholars to describe Nick as possessing a queerness and prompted analyses about his attachment to Gatsby.[9][107] For these reasons, the novel has been described as an exploration of sexual identity during a historical era typified by the societal transition towards modernity.[10][11]

Other indications of Carraway's possible homosexuality stem from a comparison of his descriptions of men and women.[108] For example, the greatest compliment that Nick gives Daisy is that she has a "low, thrilling voice",[109][110] and his description of Jordan emphasizes her masculine qualities.[111][112] Conversely, Nick's description of Tom focuses on his muscles and the "enormous power" of his body,[113][114] and in the passage where Nick first encounters Gatsby,[115] writer Greg Olear argues that "if you came across that passage out of context, you would probably conclude it was from a romance novel. If that scene were a cartoon, Cupid would shoot an arrow, music would swell, and Nick's eyes would turn into giant hearts."[109]

Different scholars draw disparate conclusions regarding the importance of Nick's sexuality to the novel. Greg Olear argues that Nick idealizes Gatsby in a similar way to how Gatsby idealizes Daisy,[109] whereas Fitzgerald scholar Tracy Fessenden posits that Nick's attraction to Gatsby serves to contrast the love story between Gatsby and Daisy.[116] In the eyes of the scholar Joseph Vogel, "a strong case can be made that the most compelling story of unrequited love—in both the novel and the film—is not between Jay Gatsby and Daisy, but between Nick and Jay Gatsby."[117]

Other scholars and writers disagree with such interpretations. Matthew J. Bolton dismisses interpretations of Nick's homosexuality as a case of what narratologists call "overreading."[118] Writer Michael Bourne believes whether or not Carraway is gay "can't be proven one way or the other—but I suspect the queer readings of Carraway say more about the way we read now than they do about Nick or The Great Gatsby."[119] American novelist Steve Erickson, writing in Los Angeles magazine, states that Carraway's fascination with Gatsby is less of his being in love with Gatsby than "Carraway, back from the war and back from the Midwest and wanting nothing more than to be Gatsby himself".[120]

Portrayals

[edit]Stage

[edit]The first actor to portray Nick Carraway in any medium was 24-year-old Ned Wever who starred in the 1926 Broadway adaptation of Fitzgerald's novel at the Ambassador Theatre in New York City.[12] The play was directed by future motion picture auteur George Cukor.[121] The production delighted audiences and garnered rave reviews from theater critics.[122]

The play ran for 112 performances and paused when its lead actor James Rennie, who portrayed Jay Gatsby, traveled to the United Kingdom to visit an ailing family member.[122] As F. Scott Fitzgerald was vacationing in Europe at the time, he never saw the 1926 Broadway play,[122] but his agent Harold Ober sent him telegrams quoting the glowing reviews of the production.[122] The success of the 1926 Broadway play led to the 1926 film adaptation by director Herbert Brenon.

Many actors have played Nick Carraway in later stage productions. In 1999, Dwayne Croft portrayed the character in John Harbison's operatic adaptation of the work performed at the New York Metropolitan Opera,[123] and Matthew Amendt portrayed Carraway in Simon Levy's 2006 stage adaptation of Fitzgerald's novel.[124] In 2023, Noah J. Ricketts played Carraway in The Great Gatsby: A New Musical,[125] and, in 2024, Ben Levi Ross played the role in Florence Welch's musical Gatsby: An American Myth.[126]

Film

[edit]Many actors have portrayed Nick Carraway in cinematic adaptations of Fitzgerald's novel. The first cinematic adaptation of The Great Gatsby was a silent film produced in 1926 and featured Neil Hamilton as Nick.[127] Reviewers praised Neil Hamilton's portrayal of Carraway,[13] but F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald purportedly loathed the 1926 film adaptation and walked out midway through a viewing of the film at a theater.[128] "We saw The Great Gatsby at the movies," Zelda later wrote to an acquaintance, "It's ROTTEN and awful and terrible and we left."[129] The film is now considered lost.[130]

In 1949, a second cinematic adaptation was undertaken starring Macdonald Carey as Nick.[131] In contrast to the 1926 adaptation, the 1949 adaptation was filmed under the strictures of the Hollywood Production Code, and the novel's plot was altered to appease Production Code Administration censors.[132] Critic Lew Sheaffer wrote in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle that Carey acquitted himself well as Gatsby's only friend.[133] Boyd Martin of The Courier-Journal opined that Carey gave a quiet and reserved performance.[134]

In 1974, Sam Waterston portrayed Nick in the third cinematic adaptation.[135] The film received poor critical reviews,[136] but Waterson's performance garnered positive reviews.[137] Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote that "Waterston is splendid as Nick, the narrator, a role that might have looked like a tour guide's except for the fact that Waterston has the presence and weight as an actor to give it a kind of moral heft."[138] Similarly, Gene Siskel noted "Waterston brings the proper mixture of halting action and determined thinking to his portrayal of Nick. He alone distinguishes The Great Gatsby from so many elephantine Hollywood productions."[139]

In 2013, Tobey Maguire portrayed Nick in the fourth cinematic adaptation.[140] In director Baz Luhrmann's 2013 adaptation, Carraway is depicted as a mental patient inside a sanitarium where he has taken to writing as a form of psychiatric therapy.[141] According to Maguire, the decision to confine Nick in a sanitarium occurred during pre-production as a collaborative idea between himself, director Baz Luhrmann, and co-screenwriter Craig Pearce.[141] Critic Jonathan Romney of The Independent opined that Tobey Maguire as Carraway was the least impressive of the cast,[142] and he lamented that Luhrmann's adaptation disappointingly painted the character as "a straw-hatted goof."[142]

Television

[edit]Lee Bowman portrayed Nick in a 1955 episode of the television series Robert Montgomery Presents adapting The Great Gatsby.[143] Reviewers felt Bowman was given little to do with the role and observed the actor "made as much out of the cousin [Nick] as was available."[144] Three years later, Rod Taylor played Nick in a 1958 episode of the television series Playhouse 90.[145]

Paul Rudd played Nick in the 2000 television adaptation.[136] Produced on a limited budget, the 2000 television adaptation greatly suffered from low production values.[146] This TV adaptation received overwhelmingly negative reviews,[147] although Paul Rudd's performance received praise.[148]

Radio

[edit]In October 2008, the BBC World Service broadcast an abridged 10-part reading of the story, read from the view of Nick Carraway by Trevor White.[149] In 2012, Bryan Dick played Carraway in a two-part BBC Radio 4 Classic Serial production.[150]

List

[edit]| Year | Title | Actor | Format | Distributor | Rotten Tomatoes | Metacritic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1926 | The Great Gatsby | Ned Wever | Stage | Broadway (Ambassador Theatre) | — | — |

| 1926 | The Great Gatsby | Neil Hamilton | Film | Paramount Pictures | 55% (22 reviews)[151] | — |

| 1949 | The Great Gatsby | Macdonald Carey | Film | Paramount Pictures | 33% (9 reviews)[152] | — |

| 1950 | The Great Gatsby | Dana Andrews[verification needed] | Radio | Family Hour of Stars | — | — |

| 1955 | The Great Gatsby | Lee Bowman | Television | Robert Montgomery Presents | — | — |

| 1958 | The Great Gatsby | Rod Taylor | Television | Playhouse 90 | — | — |

| 1974 | The Great Gatsby | Sam Waterston | Film | Paramount Pictures | 39% (36 reviews)[153] | 43 (5 reviews)[154] |

| 1999 | The Great Gatsby | Dwayne Croft | Opera | New York Metropolitan Opera | — | — |

| 2000 | The Great Gatsby | Paul Rudd | Television | A&E Television Networks | — | — |

| 2006 | The Great Gatsby | Matthew Amendt | Stage | Guthrie Theater | — | — |

| 2012 | The Great Gatsby | Bryan Dick | Radio | BBC Radio 4 | — | — |

| 2013 | The Great Gatsby | Tobey Maguire | Film | Warner Bros. Pictures | 48% (301 reviews)[155] | 55 (45 reviews)[156] |

| 2023 | The Great Gatsby | Noah J. Ricketts | Musical | Broadway (Paper Mill Playhouse/Broadway Theatre) | — | — |

| 2024 | Gatsby: An American Myth | Ben Levi Ross | Musical | American Repertory Theater | — | — |

See also

[edit]- Adaptations and portrayals of F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Nick (novel), a 2021 prequel to The Great Gatsby centering on Nick Carraway

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Only two pages of the first draft of The Great Gatsby survive. Fitzgerald enclosed them with a letter to Willa Cather in 1925. They are now in the Fitzgerald Papers collection at Princeton University.[22]

- ^ Fessenden (2005) argues that Fitzgerald struggled with his sexual orientation.[41] In contrast, Bruccoli (2002) insists that "anyone can be called a latent homosexual, but there is no evidence that Fitzgerald was ever involved in a homosexual attachment".[42]

- ^ In the original 1925 text, Fitzgerald specified the "Twenty-eighth Infantry" of the "First Division".[49] Fitzgerald corrected the text in subsequent editions to be the "Ninth Machine-Gun Battalion" of the "Third Division".[50]

- ^ West Egg is based on Great Neck, New York.[53] From 1922 to 1924, Fitzgerald resided at 6 Gateway Drive in Great Neck, New York. His neighbors included such newly wealthy personages as writer Ring Lardner, actor Lew Fields and comedian Ed Wynn.[54] These figures were regarded as nouveau riche (new rich), unlike those who came from Manhasset Neck, which sat across the bay from Great Neck—places that were home to many of New York's wealthiest established families.[55] This juxtaposition gave Fitzgerald his idea for "West Egg" and "East Egg".

- ^ Flappers were young, modern women who bobbed their hair and wore short skirts.[84][85] They also drank alcohol and had premarital sex.[86][87]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Mizener 1965, p. 190.

- ^ a b c Mizener 1965, p. 190; Marx 1964, p. 363.

- ^ a b Marx 1964, pp. 358–64.

- ^ a b c d e Marx 1964, pp. 363–64

- ^ a b c Turnbull 1962, p. 46.

- ^ a b Kerr 1996, p. 406: "It was in the 1970s that readers first began to address seriously the themes of gender and sexuality in The Great Gatsby; a few critics have pointed out the novel's bizarre homoerotic leitmotif".

- ^ a b Fraser 1979, pp. 331–332; Thornton 1979, pp. 464–466.

- ^ Vogel 2015, p. 34; Kerr 1996, pp. 412, 414; Bourne 2018.

- ^ a b Fraser 1979, pp. 331–332; Thornton 1979, pp. 464–466; Paulson 1978, p. 329; Kerr 1996, pp. 409–411; Vogel 2015, p. 34.

- ^ a b Vogel 2015, pp. 31, 51: "Among the most significant contributions of The Great Gatsby to the present is its intersectional exploration of identity.... these themes are inextricably woven into questions of race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality".

- ^ a b Paulson 1978, p. 329: Commenting upon Nick's sexual confusion, A. B. Paulson remarked in 1978 that "the novel is about identity, about leaving home and venturing into a world of adults, about choosing a profession, about choosing a sexual role to play as well as a partner to love, it is a novel that surely appeals on several deep levels to the problems of adolescent readers".

- ^ a b Playbill 1926.

- ^ a b Green 1926.

- ^ a b Mizener 1965, p. 60: "In February he put on his Show Girl make-up and went to a Psi U dance at the University of Minnesota with his old friend Gus Schurmeier as escort. He spent the evening casually asking for cigarettes in the middle of the dance floor and absent-mindedly drawing a small vanity case from the top of a blue stocking".

- ^ Mizener 1965, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b c Fitzgerald 1925, p. 3.

- ^ "In the early 1890s, shortly after marrying Mollie McQuillan, Edward Fitzgerald organized the American Rattan & Willow Works, which manufactured wicker furniture".West 2005, p. 15

- ^ a b Kazin 1951, p. 81.

- ^ a b Kazin 1951, p. 79.

- ^ Kazin 1951, p. 80.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1991, p. xxvii, Introduction: "Daisy was originally Ada, and Nick was originally Dud."

- ^ Fitzgerald 1991, pp. xvi, xx, Introduction.

- ^ Eble 1964, p. 325: "Earlier in the draft, Fitzgerald removed a number of references to a previous romance between Daisy and Nick".

- ^ Fraser 1979, p. 332: "What is perhaps revealing are Nick's original words, the words Fitzgerald began to use, then scratched out and buried beneath the curious reason Nick offers for his escape from this girl. The words he starts to use, to explain the breakup, are 'but her brother began favoring me with . . . '"

- ^ a b Bruccoli 2002, p. 178; Bruccoli 1978, p. 176.

- ^ a b c Fitzgerald 1991, p. xxviv, Introduction: "The effect of the third-person biographical form is to strengthen Nick's function as narrator and to obscure Gatsby's voice. Indeed, Gatsby speaks little in the novel; Nick reports most of what Gatsby says to him—but in Nick-ese, not in Gatsby-ese."

- ^ Kerr 1996, pp. 409–411; Vogel 2015, p. 34; Paulson 1978, p. 329; Wasiolek 1992, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Fessenden 2005, p. 28: "Fitzgerald's career records the ambient, dogging pressure to repel charges of his own homosexuality".

- ^ a b Bruccoli 2002, p. 284: According to biographer Matthew J. Bruccoli, author Robert McAlmon and other contemporaries in Paris publicly asserted that Fitzgerald was a homosexual, and Hemingway later avoided Fitzgerald due to these rumors.

- ^ Milford 1970, p. 154; Kerr 1996, p. 417.

- ^ Fessenden 2005, p. 28: "Biographers describe Fay as a 'fin-de-siècle aesthete' of considerable appeal; 'a dandy, always heavily perfumed,' who introduced the teenaged Fitzgerald to Oscar Wilde and good wine".

- ^ Fessenden 2005, p. 28

- ^ Bruccoli 2002, p. 275: "If Fay was a homosexual, as has been asserted without proof, Fitzgerald was presumably unaware of it".

- ^ Fessenden 2005, p. 30.

- ^ Fraser 1979, pp. 338–339.

- ^ Turnbull 1962, p. 259.

- ^ a b Fessenden 2005, p. 33.

- ^ Milford 1970, p. 183.

- ^ Fitzgerald & Fitzgerald 2002, p. 65.

- ^ Bruccoli 2002, p. 275: "Zelda extended her attack on Fitzgerald's masculinity by charging that he was involved in a homosexual liaison with Hemingway".

- ^ Fessenden 2005, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Bruccoli 2002, p. 275.

- ^ Kerr 1996, p. 406.

- ^ a b Turnbull 1962, p. 259; Fraser 1979, p. 334; Thornton 1979, p. 457; Kerr 1996, p. 406.

- ^ Thornton 1979, p. 457: "Being born 'masculine,' but feeling 'half-feminine,' Fitzgerald was personally interested in sexual differentiation from an early age."

- ^ Fessenden 2005, p. 31: The novel "includes some queer energies, to be sure—we needn't revisit the more gossipy strains of Fitzgerald biography to note that it's Nick who delivers the sensuous goods on Gatsby from beginning to end".

- ^ Fraser 1979, p. 330: Fitzgerald wrote that "we are all queer fish, queerer behind our faces and voices than we want any one to know or than we know ourselves. When I hear a man proclaiming himself an 'average, honest, open fellow,' I feel pretty sure that he has some definite and perhaps terrible abnormality".

- ^ a b Fitzgerald 1925, p. 1.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1925, p. 57.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1991, pp. 39, 188.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1925, p. 57: "Your face is familiar," he said, politely. "Weren't you in the First Division during the war?" "Why, yes. I was in the Twenty-eighth Infantry." "I was in the Sixteenth Infantry until June nineteen-eighteen. I knew I'd seen you somewhere before."

- ^ Fitzgerald 1991, p. 39: "Your face is familiar," he said politely. "Weren't you in the Third Division during the war?" "Why, yes. I was in the Ninth Machine-Gun Battalion." "I was in the Seventh Infantry until June nineteen-eighteen. I knew I'd seen you somewhere before."

- ^ Murphy 2010.

- ^ Bruccoli 2000, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Bruccoli 2000, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1925, p. 22.

- ^ "I wasn't actually in love, but I felt a sort of tender curiosity."Fitzgerald 1925, p. 70

- ^ Fitzgerald 1925, pp. 73, 88, 160–161, 205–207.

- ^ "Meyer Wolfsheim? No, he's a gambler." Gatsby hesitated, then added coolly: "He's the man who fixed the World's Series back in 1919".Fitzgerald 1925, p. 88

- ^ a b Fitzgerald 1991, p. xxxiii, Introduction: "An important revision in Chapter IV involves Nick's morally ambiguous role in bringing Daisy and Gatsby together.... Nick is aware that he is setting up a liaison—not just a reunion."

- ^ Fitzgerald 1925, p. 2.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1925, pp. 213–214.

- ^ a b Fitzgerald 1925, p. 212.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1925, pp. 217–218.

- ^ a b Fitzgerald 1925, p. 72.

- ^ a b c d Boyle 1969, p. 22.

- ^ Hanzo 1956, pp. 186–187; Boyle 1969, pp. 22–26.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1925, p. 24: "I forgot to ask you something, and it's important. We heard you were engaged to a girl out West."

- ^ Fitzgerald 1925, p. 57: "Your face is familiar," he said, politely. "Weren't you in the First Division during the war?"

- ^ a b c Bruccoli 2002, p. 278: "...Fitzgerald's rebuttal to Gertrude Stein's 'lost generation' catch phrase that had achieved currency through Hemingway's use of it as an epigraph for The Sun Also Rises. Whereas Stein had identified the lost generation with the war veterans, Fitzgerald insisted that the lost generation was the prewar group and expressed confidence in 'the men of the war.'"

- ^ a b c Bruccoli 2002, p. 278: "There was a lost generation in the saddle at the moment, but it seemed to him that the men coming on, the men of the war, were better; and all his old feeling that America was a bizarre accident, a sort of historical sport, had gone forever. The best of America was the best of the world."

- ^ a b c Fitzgerald 2004, p. 7: "I am tired, too, of hearing that the world war broke down the moral barriers of the younger generation. Indeed, except for leaving its touch of destruction here and there, I do not think the war left any real lasting effect. Why, it is almost forgotten right now. The younger generation has been changing all through the last twenty years. The war had little or nothing to do with it."

- ^ Weir, Jr. 1944, pp. 104–105; Fussell 1952, pp. 293–294; Steinbrink 1980, p. 160.

- ^ Bruccoli 2002, p. 90: "For the rest of Fitzgerald's life 'I didn’t get over' was an expression of regret. The scenario of battle became another wish fulfillment that he used to seek sleep during his years of insomnia".

- ^ a b Weir, Jr. 1944, pp. 104–105.

- ^ a b c d Fussell 1952, pp. 293–294.

- ^ a b Steinbrink 1980, p. 157.

- ^ Steinbrink 1980, p. 160.

- ^ a b c Fitzgerald 2004, p. 7.

- ^ a b Fitzgerald 1945, pp. 14–15: "Scarcely had the staider citizens of the republic caught their breaths when the wildest of all generations, the generation which had been adolescent during the confusion of the War, brusquely shouldered my contemporaries out of the way and danced into the limelight. This was the generation whose girls dramatized themselves as flappers..."

- ^ Fitzgerald 1945, pp. 14–15; Fitzgerald 2004, p. 7.

- ^ a b Bruccoli 2002, p. 446: "I could name many names and after those wild five years from 1919-24 women changed a little in America and settled back to something more stable. The real lost generation of girls were those who were young right after the war because they were the ones with infinite belief."

- ^ Savage 2007, pp. 206–207, 225–226; Conor 2004, p. 209.

- ^ Conor 2004, p. 209: "More than any other type of the Modern Woman, it was the Flapper who embodied the scandal which attached to women's new public visibility, from their increasing street presence to their mechanical reproduction as spectacles".

- ^ Conor 2004, pp. 210, 221.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1945, p. 16, "Echoes of the Jazz Age": The flappers, "if they get about at all, know the taste of gin or corn at sixteen".

- ^ Fitzgerald 1945, pp. 14–15, "Echoes of the Jazz Age": "Unchaperoned young people of the smaller cities had discovered the mobile privacy of that automobile given to young Bill at sixteen to make him 'self-reliant'. At first petting was a desperate adventure even under such favorable conditions, but presently confidences were exchanged and the old commandment broke down".

- ^ Fitzgerald 1945, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1945, p. 15.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1945, pp. 14, 18.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1945, pp. 15, 18.

- ^ a b Fitzgerald 1945, p. 13: "When the police rode down the demobilized country boys gaping at the orators in Madison Square, it was the sort of measure bound to alienate the more intelligent young men from the prevailing order. We didn't remember anything about the Bill of Rights until Mencken began plugging it, but we did know that such tyranny belonged in the jittery little countries of South Europe."

- ^ Fitzgerald 1945, p. 13: "If goose-livered business men had this effect on the government, then maybe we had gone to war for J. P. Morgan's loans after all."

- ^ Fitzgerald 1945, pp. 13–14: "But, because we were tired of Great Causes, there was no more than a short outbreak of moral indignation... It was characteristic of the Jazz Age that it had no interest in politics at all."

- ^ Kazin 1951, p. 83.

- ^ Ebert 1974: "The message of the novel, if I read it correctly, is that Gatsby, despite his dealings with gamblers and bootleggers, is a romantic, naive, and heroic product of the Midwest — and that his idealism is doomed in any confrontation with the reckless wealth of the Buchanans."

- ^ Mizener 1965, p. 190; Fitzgerald 1925, p. 3.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1991, p. xxviv, Introduction: Nick has a "grotesque vision of the East as 'a night scene by El Greco.'"

- ^ Hanzo 1956, p. 187.

- ^ Steinbrink 1980, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Marx 1964, p. 362.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1925, p. 45.

- ^ Kazin 1951, p. 202.

- ^ Paulson 1978, p. 326.

- ^ Friedrich 1960, p. 394.

- ^ Fraser 1979, pp. 331–332; Vogel 2015, p. 34; Kerr 1996, pp. 412, 414; Bourne 2018.

- ^ Wasiolek 1992, pp. 19–21: "I do not know how one can read the scene in McKee's bedroom in any other way, especially when so many other facts about [Nick's] [homosexual] behavior support such a conclusion."

- ^ Fraser 1979, pp. 334–335, 339–340; Wasiolek 1992, pp. 19–20; Olear 2013.

- ^ a b c Olear 2013.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1925, p. 11: "I looked back at my cousin, who began to ask me questions in her low, thrilling voice. It was the kind of voice that the ear follows up and down, as if each speech is an arrangement of notes that will never be played again."

- ^ Fraser 1979, pp. 339–340; Wasiolek 1992, pp. 19–20; Olear 2013.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1925, p. 13: "She was a slender, small-breasted girl, with an erect carriage, which she accentuated by throwing her body backward at the shoulders like a young cadet."

- ^ Fraser 1979, p. 334; Wasiolek 1992, pp. 18, 20.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1925, p. 8: "Not even the effeminate swank of his riding clothes could hide the enormous power of that body—he seemed to fill those glistening boots until he strained the top lacing, and you could see a great pack of muscle shifting when his shoulder moved under his thin coat."

- ^ Fitzgerald 1925, p. 58: "He smiled understandingly—much more than understandingly. It was one of those rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it, that you may come across four or five times in life...."

- ^ Fessenden 2005, p. 36: "Gatsby's love for Daisy, all theatricality and flourish, enacts the desire for WASP America, for the girl, green breast and green light; Nick's attraction to Gatsby, all hedges and circumspection, barely hinted at and barely contained, suggests other desires, other Americas."

- ^ Vogel 2015, p. 34.

- ^ Bolton 2010, p. 197.

- ^ Bourne 2018.

- ^ Erickson 2021.

- ^ Tredell 2007, p. 94.

- ^ a b c d Tredell 2007, p. 95.

- ^ Stevens 1999.

- ^ Skinner 2006.

- ^ Higgins & Hall 2024.

- ^ Culwell-Block 2024.

- ^ Tredell 2007, p. 96.

- ^ Howell 2013.

- ^ Mellow 1984, p. 281; Howell 2013.

- ^ Dixon 2003.

- ^ Tredell 2007, p. 98.

- ^ Brady 1946; Crowther 1949.

- ^ Sheaffer 1949, p. 4.

- ^ Martin 1949, p. 36.

- ^ Tredell 2007, p. 101.

- ^ a b Tredell 2007, p. 102.

- ^ Canby 1974; Ebert 1974; Siskel 1974, p. 33.

- ^ Canby 1974.

- ^ Siskel 1974, p. 33.

- ^ Vineyard 2013; Barsamian 2015.

- ^ a b Vineyard 2013.

- ^ a b Romney 2013, p. 46.

- ^ Hyatt 2006, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Mishkin 1955, p. 24.

- ^ Hischak 2012, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Tredell 2007, p. 103.

- ^ Joffe 2000, p. 52; Gilbert 2001, p. D3; James 2001, p. E1; Winslow 2001, p. 33.

- ^ James 2001, p. E1.

- ^ White 2007.

- ^ Forrest 2012.

- ^ Rotten Tomatoes: The Great Gatsby (1926).

- ^ Rotten Tomatoes: The Great Gatsby (1949).

- ^ Rotten Tomatoes: The Great Gatsby (1974).

- ^ Metacritic: The Great Gatsby (1974).

- ^ Rotten Tomatoes: The Great Gatsby (2013).

- ^ Metacritic: The Great Gatsby (2013).

Works cited

[edit]- Barsamian, Edward (April 15, 2015). "Is Carey Mulligan Channeling Daisy Buchanan?". Vogue. New York City: Condé Nast. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Bolton, Matthew J. (2010). "'A Fragment of Lost Words': Narrative Ellipses in The Great Gatsby". In Dickstein, Morris (ed.). Critical Insights: The Great Gatsby. Pasadena, California: Salem Press. ISBN 978-1-58765-608-8. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Bourne, Michael (April 23, 2018). "The Queering of Nick Carraway". The Millions. New York. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Boyle, Thomas E. (1969). "Unreliable Narration in 'The Great Gatsby'". The Bulletin of the Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association. 23 (1). Laramie, Wyoming: University of Wyoming: 21–26. doi:10.2307/1346578. JSTOR 1346578. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Brady, Thomas F. (October 13, 1946). "Alarum in Hollywood". The New York Times. New York City. pp. 65, 67. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

The Production Code Administration has strongly urged complete abandonment of the story because of its 'low moral tone.'... 'The Johnston office', Maibaum says, 'seems to be afraid of starting a new jazz cycle.' The Great Gatsby was first filmed in 1926 and received little criticism from the moralists of that decadent era.

- Bruccoli, Matthew J. (Spring 1978). "'An Instance of Apparent Plagiarism': F. Scott Fitzgerald, Willa Cather, and the First 'Gatsby' Manuscript". Princeton University Library Chronicle. 39 (3). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Library: 171–78. doi:10.2307/26402223. JSTOR 26402223. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Bruccoli, Matthew J., ed. (2000). F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby: A Literary Reference. New York City: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7867-0996-0. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Google Books.

- Bruccoli, Matthew J. (July 2002) [1981]. Some Sort of Epic Grandeur: The Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald (2nd rev. ed.). Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-455-8. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Canby, Vincent (March 31, 1974). "They've Turned 'Gatsby' to Goo". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Conor, Liz (June 22, 2004). The Spectacular Modern Woman: Feminine Visibility in the 1920s. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21670-0. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2023 – via Google Books.

- Crowther, Bosley (July 14, 1949). "The Screen In Review: 'The Great Gatsby,' Based on Novel of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Opens at the Paramount". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Culwell-Block, Logan (June 14, 2024). "Reviews: What Do Critics Think of Gatsby at American Repertory Theater?". Playbill. New York City. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- Dixon, Wheeler Winston (2003). "The Three Film Versions of The Great Gatsby: A Vision Deferred". Literature Film Quarterly. United Kingdom: Routledge. Archived from the original on June 5, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1974). "The Great Gatsby". RogerEbert.com. Chicago, Illinois. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Eble, Kenneth (November 1964). "The Craft of Revision: The Great Gatsby". American Literature. 36 (3). Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press: 315–26. doi:10.2307/2923547. JSTOR 2923547. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Erickson, Steve (January 4, 2021). "In a New Prequel to 'The Great Gatsby,' Nick Carraway Gets His Own Mystery". Los Angeles. Los Angeles, California. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Fessenden, Tracy (2005). "F. Scott Fitzgerald's Catholic Closet". U.S. Catholic Historian. 23 (3). Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press: 19–40. JSTOR 25154963. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott (2004). Bruccoli, Matthew J.; Baughman, Judith (eds.). Conversations with F. Scott Fitzgerald. Jackson, Mississippi: University of Mississippi Press. ISBN 1-57806-604-2 – via Google Books.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott; Fitzgerald, Zelda (2002) [1985]. Bryer, Jackson R.; Barks, Cathy W. (eds.). Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda: The Love Letters of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-9821-1713-9 – via Internet Archive.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott (1945). Wilson, Edmund (ed.). The Crack-Up. New York: New Directions. ISBN 0-8112-0051-5 – via Internet Archive.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott (1925). The Great Gatsby. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-1-4381-1454-5. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott (1991) [1925]. Bruccoli, Matthew J. (ed.). The Great Gatsby. The Cambridge Edition of the Works of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40230-1. Archived from the original on November 22, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Forrest, Robert (May 12, 2012). "BBC Radio 4 – Classic Serial, The Great Gatsby, Episode 1". BBC. London. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Fraser, Keath (Fall 1979). "Another Reading of The Great Gatsby". English Studies in Canada. 5 (3). Association of Canadian College and University Teachers of English: 330–343. doi:10.1353/esc.1979.0039. S2CID 166821868.

- Friedrich, Otto (Summer 1960). "F. Scott Fitzgerald: Money, Money, Money". The American Scholar. 29 (3). Washington, D.C.: Phi Beta Kappa Society: 392–405. JSTOR 41208658. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Fussell, Edwin S. (December 1952). "Fitzgerald's Brave New World". English Literary History. 19 (4). Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press: 291–306. doi:10.2307/2871901. JSTOR 2871901. Retrieved November 5, 2024.

- Gilbert, Matthew (January 12, 2001). "Adaption of 'Gatsby' isn't so great". The Boston Globe (Friday ed.). Boston, Massachusetts. p. D3. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Green, Abel (November 24, 1926). "The Great Gatsby". Variety. Los Angeles, California. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Hanzo, Thomas A. (1956). "The Theme and The Narrator of The Great Gatsby". Modern Fiction Studies. 2 (4). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press: 183–90. JSTOR 26273109. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- James, Caryn (January 12, 2001). "The Endless Infatuation With Getting 'Gatsby' Right". The New York Times. New York City. p. E1. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Higgins, Molly; Hall, Margaret (April 25, 2024). "Reviews: What Are Critics Saying About The Great Gatsby on Broadway?". Playbill. New York City. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- Hischak, Thomas S. (2012). American Literature on Stage and Screen: 525 Works and Their Adaptations. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-7864-6842-3. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Google Books.

- Howell, Peter (May 5, 2013). "Five Things You Didn't Know About The Great Gatsby". The Star. Toronto, Canada. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Hyatt, Wesley (2006). Emmy Award Winning Nighttime Television Shows, 1948–2004. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. pp. 49–50. ISBN 0-7864-2329-3. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Google Books.

- Joffe, Natasha (March 30, 2000). "The Not-So Great Gatsby". The Guardian (Thursday ed.). London, United Kingdom. p. 52. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Kazin, Alfred, ed. (1951). F. Scott Fitzgerald: The Man and His Work (1st ed.). New York City: World Publishing Company – via Internet Archive.

- Kerr, Frances (1996). "Feeling 'Half Feminine': Modernism and the Politics of Emotion in The Great Gatsby". American Literature. 68 (2). Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press: 405–31. doi:10.2307/2928304. JSTOR 2928304. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Martin, Boyd (July 29, 1949). "Alan Ladd, as 'Great Gatsby,' Finds That Money is a False God". The Courier-Journal (Friday ed.). Louisville, Kentucky. p. 36. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Marx, Leo (1964). The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513351-6 – via Internet Archive.

- Mellow, James R. (1984). Invented Lives: F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 281. ISBN 0-395-34412-3 – via Internet Archive.

Hollywood," [Zelda] wrote Scottie, "is not gay like the magazines say but very quiet. The stars almost never go out in public and every place closes at mid-night." They had been to see a screening of The Great Gatsby, she wrote: "It's ROTTEN and awful and terrible and we left.

- Milford, Nancy (1970). Zelda: A Biography. New York: Harper & Row. LCCN 66-20742 – via Internet Archive.

- Mishkin, Leo (May 12, 1955). "'Great Gatsby' Suffers When Cut to One Hour". The Philadelphia Inquirer (Thursday ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. p. 24. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Mizener, Arthur (1965) [1951]. The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald (2nd ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton-Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-1-199-45748-6 – via Internet Archive.

- Murphy, Mary Jo (September 30, 2010). "Eyeing the Unreal Estate of Gatsby Esq". The New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Olear, Greg (January 9, 2013). "Nick Carraway is gay and in love with Gatsby". Salon. San Francisco, California. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Paulson, A. B. (Fall 1978). "The Great Gatsby: Oral Aggression and Splitting". American Imago. 35 (3). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press: 311–30. JSTOR 26303279. PMID 754550. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Romney, Jonathan (May 19, 2013). "Gatsby: Leo gets lost in Baz's jazz". The Independent (Sunday ed.). London. p. 46. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Savage, Jon (2007). Teenage: The Creation of Youth Culture. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-03837-4 – via Internet Archive.

- Sheaffer, Lew (July 14, 1949). "'Great Gatsby' Expertly Catches Restless Spirit of the Jazz Age". The Brooklyn Eagle (Thursday ed.). Brooklyn, New York. p. 4. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Siskel, Gene (April 5, 1974). "'Gatsby': Call it 'Love on Long Island' and let yourself like it". Chicago Tribune (Friday ed.). Chicago, Illinois. p. 33. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Skinner, Quinton (July 26, 2006). "The Great Gatsby". Variety. Los Angeles, California. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- Steinbrink, Jeffrey (1980). "'Boats Against the Current': Mortality and the Myth of Renewal in The Great Gatsby". Twentieth Century Literature. 26 (2). Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press: 157–70. doi:10.2307/441372. JSTOR 441372. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Stevens, David (December 29, 1999). "Harbison Mixes Up A Great 'Gatsby'". The New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on June 5, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- "The Great Gatsby (1926)". Rotten Tomatoes. New York City: NBCUniversal. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- "The Great Gatsby (1949)". Rotten Tomatoes. New York City: NBCUniversal. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- "The Great Gatsby (1974)". Metacritic. Indian Land, South Carolina: Red Ventures. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- "The Great Gatsby (1974)". Rotten Tomatoes. New York City: NBCUniversal. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- "The Great Gatsby (2013)". Metacritic. Indian Land, South Carolina: Red Ventures. Archived from the original on August 21, 2018. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- "The Great Gatsby (2013)". Rotten Tomatoes. New York City: NBCUniversal. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- "The Great Gatsby (1926): Cast". Playbill. New York City. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Thornton, Patricia Pacey (Winter 1979). "Sexual Roles in The Great Gatsby". English Studies in Canada. 5 (4): 457–468. doi:10.1353/esc.1979.0051. S2CID 166260439.

Nick's is a divided nature, torn between traditional and experimental, masculine and feminine...

- Tredell, Nicolas (February 28, 2007). Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby: A Reader's Guide. London: Continuum Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8264-9010-0. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Turnbull, Andrew (1962). Scott Fitzgerald. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. LCCN 62-9315 – via Internet Archive.

- Vineyard, Jennifer (May 6, 2013). "A Very Thoughtful Tobey Maguire on The Great Gatsby, Mental Health, and On-Set Injuries". Vulture. New York City: Vox Media. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Vogel, Joseph (2015). "'Civilization's Going to Pieces': The Great Gatsby, Identity, and Race, From the Jazz Age to the Obama Era". The F. Scott Fitzgerald Review. 13 (1). University Park, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press: 29–54. doi:10.5325/fscotfitzrevi.13.1.0029. JSTOR 10.5325/fscotfitzrevi.13.1.0029. S2CID 170386299. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Wasiolek, Edward (1992). "The Sexual Drama of Nick and Gatsby". International Fiction Review. 19 (1). Fredericton, Canada: University of New Brunswick Libraries - UNB: 14–22. Archived from the original on July 21, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Weir, Jr., Charles (Winter 1944). "'An Invite with Gilded Edges': A Study of F. Scott Fitzgerald". The Virginia Quarterly Review. 20 (1). Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia: 100–13. JSTOR 26441596. Retrieved October 31, 2024.

- West, James L. W. (2005). The Perfect Hour: The Romance of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ginevra King, His First Love. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6308-6 – via Internet Archive.

- White, Trevor (December 10, 2007). "BBC World Service Programmes – The Great Gatsby". BBC. London. Archived from the original on October 3, 2010. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- Winslow, Harriet (January 13, 2001). "A&E is trying, but maybe "Gatsby" film can't be done". St. Louis Dispatch (Saturday ed.). St. Louis, Missouri. p. 33. Retrieved July 15, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.