Notgeld (German for 'emergency money' or 'necessity money') is money issued by an institution in a time of economic or political crisis. The issuing institution is usually one without official sanction from the central government. This usually occurs when not enough state-produced money is available from the central bank. In particular, notgeld generally refers to money produced in Germany and Austria during World War I and the Interwar period. Issuing institutions could be a town's savings banks, municipalities and private or state-owned firms. Nearly all issues contained an expiry date, after which time they were invalid. Issues without dates ordinarily had an expiry announced in a newspaper or at the place of issuance.

Notgeld was mainly issued in the form of (paper) banknotes. Sometimes other forms were also used: coins, leather, silk, linen, wood, postage stamps, aluminium foil, coal, and porcelain; there are also reports of elemental sulfur being used, as well as all sorts of re-used paper and carton material (e.g. playing cards). These pieces made from playing cards are extremely rare and are known as Spielkarten, the German word for 'playing cards'.

Notgeld was a mutually-accepted means of payment in a particular region or locality, but notes could travel widely. Some cases of Notgeld could better be defined as scrip, which were essentially coupons redeemable only at specific businesses. However, the immense volume of issues produced by innumerable municipalities, firms, businesses, and individuals across Germany blurred the definition. Collectors tend to categorize by region or era rather than issuing authority (see below). Notgeld is different from occupation money (e.g. Japanese invasion money) that is issued by an occupying army during a war.

Germany

[edit]Dr Arnold Keller, historian and orientalist, classified German Notgeld into different periods. Keller edited a magazine called Das Notgeld during the "collector phase" of Notgeld issuance. He compiled a series of catalogs in the years afterward. Although incomplete in many cases, his work formed the foundations of the hobby.

Notgeld in World War I

[edit]

Notgeld was released even before Germany entered World War I. On 31 July 1914 three notes were issued by the Bürgerliches Brauhaus GmbH of Bremen[1] (a brewery). This was due to hoarding of coins by the population in the days before war was declared. The first period of Notgeld continued until the end of 1914, but mostly ceased once the German Reichsbank made up for the shortage with issues of small denomination paper notes and coins of cheaper metal.

As the war dragged on, acute monetary shortages could not be met by the German central bank, leading to a new period of Notgeld beginning in 1916. Additionally, the non-precious metals used to mint lower value coins were needed to produce war supplies. Dr Keller arranged this period into two catalogs: Kleingeldscheine for issues of less than 1 Mark face value and Grossgeldscheine for values 1 Mark and higher. This period of issue came to a close in 1919.[2]

World War I prison camp money

[edit]Although camp money used by prisoners of war was different from Notgeld, collectors inevitably lumped this material into the hobby. The period covered the entire war, 1914–1918. This field of collecting may include World War II issues, though this covers only notes circulated in concentration camps, as the German Luftwaffe in charge of prisoners of war prepared a general issue of notes for all camps under their direction.

Collector series

[edit]

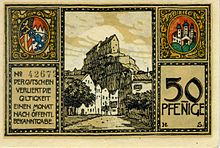

Though the production of Notgeld was initially amateurish, with many set by typewriter or even handwritten, collectors soon appeared on the scene to take hold of the expired 1914 stock. With the next wave of issues in the latter half of the war, Notgeld production was handled by professional printers. These issues incorporated pleasing designs, and a new reason for hoarding came into being.

As the issuing bodies realized this demand, they began to issue notes in 1920, well after their economic necessity had ended. They may have been motivated by the success of Austrian collector Notgeld earlier in the year (see below). Notes were issued predominantly in 1921 and were usually extremely colorful. These depicted many subjects, such as local buildings, local scenery and folklore, as well as politics. Many were released in series of 6, 8, or more notes of the same denomination, and tell a short story, with often whimsical illustrations. Often, they were sold to collectors in special envelope packets printed with a description of the series.

Keller published information on releases in his magazine Das Notgeld. Often, he used his publication to criticize issuers for charging collectors more money for the series than their face value.

These collector-only sets, which were never intended to circulate, were known as Serienscheine (pieces issued as a part of a series). Quite often, the validity period of the note had already expired when the Notgeld was issued. As such, they are usually found in uncirculated condition, and are most favored by collectors all over the world.

1922 and 1923: Hyperinflation

[edit]

In 1922, due to uncontrolled printing of money, inflation started to get out of control in Germany, culminating in hyperinflation. Throughout the year, the value of the mark deteriorated faster and faster, and new money was issued in higher and higher denominations. The Reichsbank could not cope with the logistics of providing all these new notes, and Notgeld was again issued—this time in denominations of hundreds and then thousands of Marks.

By July 1923, the Reichsbank had totally lost control of the economy. Notgeld flooded the economy; it was issued by any city, town, business, or club that had access to a printing press, in order to meet the ever-increasing rise in prices. Even Serienscheine were being hand-stamped with large denominations to meet the demand. By September, Notgeld was denominated in the tens of millions; by October, in billions; by November, trillions.

On November 12, the Reichsbank declared the Mark to be valueless, and ceased all issuance. By now, Notgeld was being denominated in the form of commodities or other currencies: wheat, rye, oats, sugar, coal, wood, quantities of natural gas, and kilowatt-hours of electricity. These pieces were known as Wertbeständige, or notes of "fixed value". There were also Notgeld coins that were made of compressed coal dust. These became quite rare, as most of them were eventually traded with the coal merchant issuer for actual coal and some may have even been burned as fuel.

Goldmark Notgeld

[edit]In January 1924, the Reichsbank fixed the value of the new Rentenmark in gold. One U.S. dollar was now equivalent to 4.2 Rentenmark (or 4.2 trillion old Papiermark, which were permitted to be exchanged beginning 30 August 1924). Until that date, a few municipalities issued Notgeld with denominations of 4.2 Mark or multiples or fractions of that. After that date, Goldmarkscheine of regular denominations were briefly issued, until the Reichsbank forbade any further interference in the economy by local authorities.

Bausteine

[edit]During the Interwar period, local municipalities and civic groups capitalized on the public memories of Notgeld by issuing certificates aimed at collectors, to raise funds for various building projects. These "Building Blocks" (Bausteine) tended to be of relatively high face value and issued in very limited numbers.

Notgeld after World War II

[edit]The Reichsbank kept strict control of the economy during World War II, and forbade local authorities from independently meeting money shortages. After Germany's defeat, the Allied Military Control issued currencies for each of their respective areas of control, but did not alleviate coin scarcity. The dire situation after the war forced municipalities to once again issue Notgeld to help the population meet small change needs. Finally, the Currency Reform of June 1948 created the Deutsche Mark and prohibited issuance of Notgeld. Apart from commemorative pieces issued sporadically, the era of Notgeld in Germany came to a close.

Austria

[edit]Revolution of 1848

[edit]

Austrian municipalities experienced coin shortages during the revolution of 1848, especially in the Czech towns, and therefore many municipalities and industrial concerns issued Notgeld as a temporary measure. By 1850, the state finances were in such an order as to render them unnecessary, though certain parts of Hungary still experienced shortages as late as 1860, requiring Notgeld-type issues.

World War I

[edit]As in Germany, municipalities in Austria-Hungary issued Notgeld at the beginning of World War I. In most cases, small change scarcity was severest in the industrial Czech towns of Bohemia and Moravia. From the end of the war into 1919, German-speaking towns of the new Czechoslovakia issued Grossgeldscheine notes until the authorities forbade them to do so.

Prison camp money

[edit]As with Germany, collectors tended to lump Austro-Hungarian prison camp money in with Notgeld. Most issues date from 1916–1917, with the majority of camps situated in Austria proper, Hungary, and Czech territories.

Collector series

[edit]In 1920, hundreds of small towns across Upper and Lower Austria, but also many towns in Salzburg, Tyrol, and Styria, issued sets of collectible Notgeld, usually in three denominations with expiry dates of three months from issuance. Nearly all were printed on thin paper, often in runs (Auflage) of different colors or shades. Some of these notes actually circulated, but the vast majority entered private collections, and the scheme's success in raising funds for destitute town budgets convinced German towns to do the same thing (see above).

After the initial run of regular series, there were numerous releases of "special issues" (Sonderscheine) featuring different designs and denominations, fanciful overprints, or the same design as the general issues but in expensive metallic inks on different paper types. Many of these special issues were printed in very small quantities in order to charge premiums to collectors. Groups of rural villages issued Sonderscheine, even though some had populations of only a few dozen inhabitants.

Depression-era Schwundgeld

[edit]In a bid to increase economic activity, several depressed municipalities in the Alps regions of Austria experimented with demurrage features in their Notgeld during the period 1932–1934. As the notes lost value (Schwund) over time, the idea was to convince holders to spend them quickly, thereby spurring economic activity. Notes had dated spaces for demurrage coupons to be affixed to them, and each one lessened the total value as they were added. The effort was unsuccessful because the scale of the experiment was too small to show any benefit.[3]

In other countries

[edit]Ireland (1689–1691)

[edit]

The forces of James II minted coins in base metal (copper, brass, pewter) during the Williamite War in Ireland, which were known as gun money, because some of the metal was sourced from melted-down cannon. It was intended that, in the event of James' victory, the coins could be exchanged for real silver coins. They were also stamped with the month of issue so that soldiers could claim interest on their wages. As James lost the war, that replacement never took place, but the coins were allowed to circulate at much reduced values before the copper coinage was resumed.

Sweden (1715–1719)

[edit]In Sweden, between 1715 and 1719, 42 million coins with the nominal value 1 daler silver were manufactured, but made in copper, with a much smaller metal value. All silver coins were collected by the government, which replaced them with the copper coins. They were called nödmynt ('emergency coins'). This was done to finance the Great Northern War. The government promised to exchange them into the correct value at a future time, a kind of bond made in metal. Only a small part of this value was ever paid.

Belgium (1914–1918)

[edit]

Throughout the German occupation of Belgium during World War I there was a shortage of official coins and banknotes in circulation. As a result, around 600 communes, local governments and companies issued their own unofficial "necessity money" (French: monnaie de nécessité, Dutch: noodgeld) to enable the continued functioning of the local economies.[4] These usually took the form of locally produced banknotes, but a few types of coins were also issued in towns and cities. In 2013, the National Bank of Belgium's museum digitized its collection of Belgian Notgeld, which is available online.[5]

France (1914–1927)

[edit]Between 1914 and 1927, large amounts of monnaie de nécessité were issued in France and its North African colonies during the economic crisis caused by World War I. Among the issuing authorities were companies and local chambers of commerce.

Others

[edit]The concept of Notgeld as temporary payment certificates is nearly as old and widespread as paper money itself[citation needed]. Other countries using Notgeld-style temporary money include the following (date ranges are approximate):

- Anglo-Egyptian Sudan[6]

- Algeria[6]

- Angola[6]

- Argentina[6]

- Armenia[6]

- Australia[6]

- Azores[6]

- Cameroons[6]

- Cape Verde Islands[6]

- Ceylon[6]

- China,[6] during its civil war, 1916–1949

- Cyprus[6]

- Czech Republic and Slovakia[6] (Czechoslovakia), during the 1848 revolution, 1848–1849; during and after World War I, 1916–1920

- Denmark[6]

- Estonia[6]

- Ethiopia[6]

- Fiji[6]

- Finland,[6] 1918–1922

- France[6]

- French Equatorial Africa[6]

- French Indo-China[6]

- French Oceania[6]

- French Somaliland[6]

- French West Africa[6]

- Gabon[6]

- German East Africa[6]

- German Samoa[6]

- German New Guinea[6]

- German Southwest Africa[6]

- Gibraltar[6]

- Grand Comoro[6]

- Great Britain[6]

- Greece[6]

- Greenland[6]

- Hong Kong[6]

- Hungary,[6] during the 1848 revolution, 1848–1849 and sporadically thereafter; during and after World War I, 1914–1922

- Iceland[6]

- India[6]

- Indian princely states, during the British Raj, c. 1890–1948

- Isle of Man[6]

- Italy[6]

- Japan,[6] during its feudal period (so-called Hansatsu), 1600–1871

- Kenya[6]

- Latvia[6]

- Liechtenstein[6]

- Lithuania[6]

- Luxemburg[6]

- Macao[6]

- Madagascar[6]

- Madeira[6]

- Martinique[6]

- Monaco[6]

- Montenegro[6]

- Morocco[6]

- Mozambique[6]

- Netherlands[6]

- New Caledonia[6]

- New Zealand[6]

- Norway[6]

- Philippines (Emergency circulating notes)[6]

- Poland, 1914–1922

- Portugal[6]

- Portuguese Guinea[6]

- Revolutionary France, 1791–1800

- Rhodesia[6]

- Romania[6]

- Russian Poland[6]

- Russia[6]

- Russian Baltic governorates, 1860–1880

- São Tomé and Príncipe[6]

- Senegal[6]

- Serbia[6]

- Soviet Russia, including territories to become Soviet republics (such as Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan), 1917–1924

- Spain[6]

- Sudan[6]

- Switzerland[6]

- Syria[6]

- Tunisia[6]

- United States, during the Civil War 1861–1865 (for example, Sutler scrip); during the depression, 1930–1940; during the cent shortage, 1974

- Uruguay[6]

- Yugoslavia,[6] 1918–1920

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Coffing, Courtney (1986). Perspectives in Numismatics. Chicago Coin Club. ISBN 0-89005-438-X.

- ^ Eiland, Murray (2010). "Heraldry on German Notgeld". The Armiger's News. 32 (3): 1–3, 12 – via academia.edu.

- ^ Richter, Rudolf (1993). Notgeld Österreich: Deutsch-Österreich und Nachfolgestaaten mit Nebengebieten ab 1918. H. Gietl Verlag. p. 115. ISBN 9783924861117.

- ^ "Billets de nécessité belges de la Première Guerre mondiale". National Bank of Belgium Museum. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ "Billets de nécessité belges - catalogue". National Bank of Belgium Museum. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw Coffing, Courtney L. (2000). A Guide & Checklist: World Notgeld, 1914-1947 and Other Local Issue Emergency Money (2nd ed.). Iola: Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-810-7.

External links

[edit] Media related to Notgeld at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Notgeld at Wikimedia Commons- Info and pictures about German notgeld

- Info about notgeld and collecting German notgeld

- German and Austrian Notgeld Banknotes

- High-resolution images of many German Notgeld Banknotes

- Information and pictures to all Austrian Notgeld periods

- Notgeld at notafilia.com.br

- Annotated Directory of German Series Notes

- Notgeld photographs on Flickr

- Belgian emergency money from the First World War: an online collection (in French)

- Catalog of German notgeld coins (Numista)

- Catalog of German notgeld banknotes (Numista)

- Catalog of French notgeld coins (Numista)

- Catalog of French notgeld banknotes (Numista)