Ogden Nash | |

|---|---|

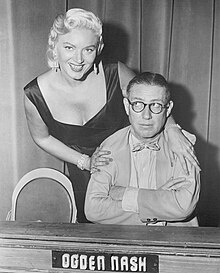

Nash and Dagmar from the television game show Masquerade Party, 1955 | |

| Born | Frederic Ogden Nash August 19, 1902 |

| Died | May 19, 1971 (aged 68) Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Resting place | East Cemetery, North Hampton, New Hampshire[1][2] |

| Education | Harvard University (for 1 year) |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Spouse | Frances Leonard |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Fernanda Eberstadt (granddaughter) Nicholas Eberstadt (grandson) |

Frederic Ogden Nash (August 19, 1902 – May 19, 1971) was an American poet well known for his light verse, of which he wrote more than 500 pieces. With his unconventional rhyming schemes, he was declared by The New York Times to be the country's best-known producer of humorous poetry.[3]

Early life

[edit]Nash was born on August 19, 1902, in Rye, New York, on Milton Point,[4] the son of Mattie (Chenault) and Edmund Strudwick Nash.[5][6] Nash was baptized at Christ's Church.[4] At two years old, his family had a house called "Ramaqua", on 50 acres near Port Chester.[4][7] His father owned and operated a turpentine company.[7]

Because of business obligations, the family often relocated. Nash was descended from Abner Nash, an early governor of North Carolina. The city of Nashville, Tennessee, was named after Abner's brother, Francis, a Revolutionary War general.[8][9]

Throughout his life, Nash loved to rhyme. "I think in terms of rhyme, and have since I was six years old", he stated in a 1958 news interview.[10] He had a fondness for crafting his own words whenever rhyming words did not exist but admitted that crafting rhymes was not always the easiest task.[10]

His family lived briefly in Savannah, Georgia, in a carriage house owned by Juliette Gordon Low, the founder of the Girl Scouts of the USA. He wrote a poem about Mrs. Low's House. After graduating from St. George's School in Newport County, Rhode Island, Nash entered Harvard University in 1920, only to drop out a year later.

He taught at St. George's for one year and then returned to New York.[11] There, he took up selling bonds about which Nash reportedly quipped, "Came to New York to make my fortune as a bond salesman and in two years sold one bond—to my godmother.[3] However, I saw lots of good movies."[11] Nash then took a position as a writer of the streetcar card ads for Barron Collier,[11] a company that had employed F. Scott Fitzgerald, another resident of Baltimore (Nash's permanent home). While working as an editor at Doubleday, he submitted some short rhymes to The New Yorker. The editor Harold Ross wrote Nash to ask for more: "They are about the most original stuff we have had lately."[12] Nash spent three months in 1931 working on the editorial staff for The New Yorker.[11][13]

In 1931, Nash published his first collection of poems, Hard Lines, the same year, which earned him national recognition.[14] Some of his poems reflected an anti-establishment feeling. For example, one verse, titled "Common Sense", asks:

Why did the Lord give us agility,

If not to evade responsibility?

Writing career

[edit]

When Nash was not writing poems, he made guest appearances on comedy and radio shows and toured the United States and the United Kingdom and gave lectures at colleges and universities.

Nash was regarded with respect by the literary establishment, and his poems were frequently anthologized, even in serious collections such as Selden Rodman's 1946 A New Anthology of Modern Poetry.

Nash was the lyricist for the 1943 Broadway musical One Touch of Venus and collaborated with the librettist S. J. Perelman and the composer Kurt Weill. The show included the notable song "Speak Low". He also wrote the lyrics for the 1952 revue Two's Company.

Nash and his love of the Baltimore Colts were featured in the December 13, 1968, issue of Life magazine,[15] with several poems about the American football team matched to full-page pictures. Entitled "My Colts, verses and reverses", the issue includes his poems and photographs by Arthur Rickerby: "Mr. Nash, the league leading writer of light verse (Averaging better than 6.3 lines per carry), lives in Baltimore and loves the Colts", it declares. The comments further describe Nash as "a fanatic of the Baltimore Colts, and a gentleman." Featured on the magazine cover is the defensive player Dennis Gaubatz, number 53, in midair pursuit with this description: "That is he, looming 10 feet tall or taller above the Steelers' signal caller ... Since Gaubatz acts like this on Sunday, I'll do my quarterbacking Monday." Memorable Colts Jimmy Orr, Billy Ray Smith, Bubba Smith, Willie Richardson, Dick Szymanski and Lou Michaels contribute to the poetry.

Among Nash's most popular writings were a series of animal verses, many of which featured his off-kilter rhyming devices. Examples include "If called by a panther / Don't anther"; "Who wants my jellyfish? / I'm not sellyfish!"; "The one-L lama, he's a priest. The two-L llama, he's a beast. And I will bet a silk pajama: there isn't any three-L lllama!" Nash later appended the footnote "*The author's attention has been called to a type of conflagration known as a three-alarmer. Pooh."[16]

The best of his work was published in 14 volumes between 1931 and 1972.

Poetic style

[edit]Nash was best known for surprising, pun-like rhymes, sometimes with words deliberately misspelled for comic effect, as in his retort to Dorothy Parker's humorous dictum, "Men seldom make passes / At girls who wear glasses":

A girl who's bespectacled

May not get her nectacled

In this example, the word "nectacled" sounds like the phrase "neck tickled" when rhymed with the previous line.

Sometimes the words rhyme by mispronunciation rather than misspelling, as in:

Farewell, farewell, you old rhinoceros,

I'll stare at something less prepoceros

Another typical example of rhyming by combining words occurs in "The Adventures of Isabel", when Isabel confronts a witch who threatens to turn her into a toad:

She showed no rage and she showed no rancor,

But she turned the witch into milk, and drank her.

Nash often wrote in an exaggerated verse form, with pairs of lines that rhyme, but are of dissimilar length and irregular meter:

Once there was a man named Mr. Palliser and he asked his wife, May I be a gourmet?

And she said, You sure may.

Nash's poetry was often a playful twist of an old saying or poem. For one example, in a twist on Joyce Kilmer's poem "Trees" (1913) – which contains the lines "I think that I shall never see / a poem lovely as a tree" – Nash adds: "Indeed, unless the billboards fall / I'll never see a tree at all."[17]

Other poems

[edit]Nash, a baseball fan, wrote a poem titled "Line-Up for Yesterday", an alphabetical poem listing baseball immortals.[18] Published in Sport magazine in January 1949, the poem pays tribute to highly respected baseball players and to his own fandom, in alphabetical order. Lines include:[19]

C is for Cobb, Who grew spikes and not corn, And made all the basemen Wish they weren't born.

D is for Dean, The grammatical Diz, When they asked, Who's the tops? Said correctly, I is.

E is for Evers, His jaw in advance; Never afraid To Tinker with Chance.

F is for Fordham And Frankie and Frisch; I wish he were back With the Giants, I wish.

Nash wrote humorous poems for each movement of the Camille Saint-Saëns orchestral suite The Carnival of the Animals, which are sometimes recited when the work is performed. The original recording of this version was made by Columbia Records in the 1940s, with Noël Coward reciting the poems and Andre Kostelanetz conducting the orchestra.

He wrote a humorous poem about the IRS and income tax titled Song for the Saddest Ides, a reference to March 15, the ides of March, when federal taxes were due at the time.[20]

Many of his poems, reflecting the times in which they were written, presented stereotypes of different nationalities. For example, in "Genealogical Reflections" he writes:

No McTavish

Was ever lavish

In "The Japanese", published in 1938, Nash presents an allegory for the expansionist policies of the Empire of Japan:

How courteous is the Japanese;

He always says, "Excuse it, please."

He climbs into his neighbor's garden,

And smiles, and says, "I beg your pardon";

He bows and grins a friendly grin,

And calls his hungry family in;

He grins, and bows a friendly bow;

"So sorry, this my garden now."[21]

He published some poems for children, including "The Adventures of Isabel", which begins:

Isabel met an enormous bear,

Isabel, Isabel, didn't care;

The bear was hungry, the bear was ravenous,

The bear's big mouth was cruel and cavernous.

The bear said, "Isabel, glad to meet you,

How do, Isabel, now I'll eat you!"

Isabel, Isabel, didn't worry.

Isabel didn't scream or scurry.

She washed her hands and she straightened her hair up,

Then Isabel quietly ate the bear up.

Personal life

[edit]In 1931, he married Frances Leonard, of Baltimore.[22][23][24][25]

In 1934, Nash moved his family to his in-laws' mansion in Guilford, Baltimore, Maryland, where he remained until his death in 1971.[26] Nash thought of Baltimore as home. After his return from a brief move to New York, he wrote: "I could have loved New York had I not loved Balti-more."[27]

Nash's daughter Isabel was married to noted photographer Frederick Eberstadt. His granddaughter, Frances R. Smith,[28] is an author. Another granddaughter, Fernanda Eberstadt, is an acclaimed author, and his grandson is political economist Nicholas Eberstadt. Nash had one other daughter, author Linell Nash Smith.[29][30]

Nash died at Baltimore's Johns Hopkins Hospital on May 19, 1971, of Crohn's Disease,[31][32] aggravated by a lactobacillus infection transmitted by improperly prepared coleslaw.[33][3] He is buried in East Cemetery in North Hampton, New Hampshire.[34]

At the time of his death in 1971, The New York Times said his "droll verse with its unconventional rhymes made him the country's best-known producer of humorous poetry."[3]

Legacy

[edit]Musical

[edit]Nash at Nine, a Broadway musical that set some of Nash's poems as lyrics to music by Milton Rosenstock, premiered at the Helen Hayes Theatre on Broadway on May 17, 1973, and closed on June 2, 1973, after five previews and 21 performances. Directed by Martin Charnin, the show featured Steve Elmore, Bill Gerber, E. G. Marshall, Richie Schechtman, and Virginia Vestoff.[35]

Postage stamp

[edit]The US Postal Service released a postage stamp featuring Ogden Nash and text from six of his poems on the centennial of his birth on August 19, 2002. The six poems are "The Turtle", "The Cow", "Crossing The Border", "The Kitten", "The Camel", and "Limerick One". The stamp is the 18th in the Literary Arts section.[36][37] The first issue ceremony took place in Baltimore on August 19 at the home that he and his wife Frances shared with his parents on 4300 Rugby Road, where he did most of his writing.

Biography

[edit]A biography, Ogden Nash: the Life and Work of America's Laureate of Light Verse, was written by Douglas M. Parker and published in 2005. with a paperback edition issued in 2007.[38][39] Written with the cooperation of the Nash family, the book quotes extensively from Nash's personal correspondence as well as his poetry.

Works

[edit]- Hard Lines. Simon and Schuster, 1931. OCLC 185166483

- I'm a Stranger Here Myself. Little Brown & Co, 1938 (reissued Buccaneer Books, 1994. ISBN 1-56849-468-8)

- The Face Is Familiar: The Selected Verse of Ogden Nash. Garden City Publishing Company, Inc., 1941.

- Good Intentions. Little Brown & Co, 1942. ISBN 978-1-125-65764-5

- Many Long Years Ago. Little Brown & Co, 1945. ASIN B000OELG1O

- Versus. Little, Brown, & Co, 1949.

- Private Dining Room. Little Brown & Co, 1952. ASIN B000H1Z8U4

- The Moon Is Shining Bright As Day. J. B. Lippincott Co, 1953. ISBN 0397302444

- You Can't Get There from Here. Little Brown & Co, 1957.

- Everyone but Thee and Me. Boston : Little, Brown, 1962.

- Marriage Lines. Boston : Little, Brown, 1964.

- There's Always Another Windmill. Little Brown & Co, 1968. ISBN 0-316-59839-9

- Bed Riddance. Little Brown & Co, 1969. ASIN B000EGGXD8

- Collected Verse from 1929 On. Lowe & Brydone (Printers) Ltd., London, for J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd. 1972

- The Old Dog Barks Backwards. Little Brown & Co, 1972. ISBN 0-316-59804-6

- Custard and Company. Little Brown & Co, 1980. ISBN 0-316-59834-8

- Ogden Nash's Zoo, with Étienne Delessert. Stewart, Tabori, and Chang, 1986. ISBN 0-941434-95-8

- Pocket Book of Ogden Nash. Pocket, 1990. ISBN 0-671-72789-3

- Candy Is Dandy, with Anthony Burgess, Linell Smith, and Isabel Eberstadt. Carlton Books Ltd, 1994. ISBN 0-233-98892-0

- Selected Poetry of Ogden Nash. Black Dog & Levanthal Publishing, 1995. ISBN 978-1-884822-30-8

- The Tale of Custard the Dragon, with Lynn Munsinger. Little, Brown Young Readers, 1998. ISBN 0-316-59031-2

- Custard the Dragon and the Wicked Knight, with Lynn Munsinger. Little, Brown Young Readers, 1999. ISBN 0-316-59905-0

- List of poems

| Title | Year | First published | Reprinted/collected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carnival of animals | 1950 | Nash, Ogden (January 7, 1950). "Carnival of animals". The New Yorker. Vol. 25, no. 46. p. 26. |

References

[edit]- ^ Academy of American Poets. "Death, Be Not Proud: The Graves of Poets". Poets.org. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ Brady, John (September 11, 2011). "NASH-ional TREASURE Events in Rye, NY". blog.ogdennash.org. Archived from the original on October 7, 2011. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Krebs, Albin (May 20, 1971). "Ogden Nash, Master of Light Verse, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

Ogden Nash, whose droll verse with its unconventional rhymes made him the country's best-known producer of humorous poetry, died yesterday at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. His age was 68.

- ^ a b c Beechey, Alan (March 18, 2011). "Recognizing Ogden Nash, Native Son of Rye". MyRye.com. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ Lehman, David (2006). The Oxford Book of American Poetry. Oxford University Press. p. 475. ISBN 978-0-19-516251-6.

- ^ "Ogden Nash Biography - life, family, children, parents, death, school, book, information, born, movie". notablebiographies.com. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ a b "The Search for Ogden Nash's Birthplace". blog.ogdennash.org. July 15, 2012. Archived from the original on September 13, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "NC Highway Markers, printable view". North Carolina Office of Archives and History. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- ^ Powell, William (ed.). Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, v4. p. 358.

- ^ a b Boyle, Hal (December 1, 1958). "Ogden Nash Finds Light Verse Doesn't Flow Easy". Prescott Evening Courier. Associated Press. Retrieved October 19, 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d Phillips, Louis (2005). "Reviewed work(s): Ogden Nash: The Life and Work of America's Laureate of Light Verse by Douglas M. Parker". The Georgia Review. 59 (4): 961. JSTOR 41402690.

- ^ "Ogden Nash – Master of Pace and Rhyme". The Attic. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- ^ Hasley, Louis (1971). "The Golden Trashery of Ogden Nashery". The Arizona Quarterly. 27 (3): 242.

- ^ Vries, Lloyd (July 19, 2002). "Postage Stamp Bash / For Ogden Nash". CBS News. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ^ Nash, Ogden (December 13, 1968). "My Colts, verses and reverses". Life. Vol. 65, no. 24. p. 75. ISSN 0024-3019. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ^ "The Lama – Ogden Nash". wonderingminstrels.blogspot.com. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ Nash, Ogden, "Song of the Open Road", The Face Is Familiar (Garden City Publishing, 1941), p. 21.

- ^ Wiles, Tim (March 31, 1996). "Who's on Verse?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 17, 2000. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ "Baseball Almanac". Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ Dew, Harold (1946). Poems Past and Present, 1946 Edition. Vancouver, BC, Canada: The Wrigley Printing Co. Ltd. p. 244-245.

- ^ Nash, Ogden. I'm a Stranger Here Myself (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1938), p. 35.

- ^ "Baltimore's famous literary figures and their favorite local haunts". Chicago Tribune. November 7, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ Rasmussen, Fred (June 17, 1994). "Frances Leonard Nash, poet's widow active in charities, patron of the arts". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 20, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "Ogden Nash". baltimoreauthors.ubalt.edu. Archived from the original on November 6, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ "Former Ogden Nash house in Guilford [Pictures]". Baltimore Sun. June 20, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ Dennies, Nathan (November 27, 2018). "Ogden Nash at 4300 Rugby Road". Explore Baltimore Heritage. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Frances R. "Poet left indelible mark on family, society". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "Linell Chenault Smith, an author, horse enthusiast and last surviving daughter of poet Ogden Nash, dies". Baltimore Sun. August 20, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "MISS LINELL NASH BECOMES ENGAGED; Daughter of Poet Will Be Wed to John M. Smith, Who Served in Pacific With Army". The New York Times. Special to THE NEW YORK TIMES. June 25, 1951. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "Famous Persons With UC/Crohn's Disease". The J-Pouch Group. April 1, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ The Guilford News, Summer 2019.

- ^ Dennies, Nathan. "Ogden Nash at 4300 Rugby Road". Explore Baltimore Heritage. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "Guide to the Ogden Nash Letters, 1968–1969". University of New Hampshire. December 21, 2007. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ^ "Nash at Nine (Broadway, Helen Hayes Theatre, 1973)". www.playbill.com. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ "Pulitzer Prize-Winning Author Gets 'Stamp of Approval': Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Stamp to Be Issued at Her Cross Creek, FL, Home". U. S. Postal Service. February 21, 2008. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ^ "Literary Arts: 1979–present". U. S. Postal Service. Archived from the original on June 30, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ^ Parker, Douglas M. (2005). Ogden Nash: The Life and Work of America's Laureate of Light Verse. Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 978-1-56663-637-7.

- ^ Schoettler, Carl (June 12, 2005). "Hard life of Billie Holiday; smart verse of Ogden Nash; kicking the war habit". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Ogden Nash at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Ogden Nash at Wikiquote Media related to Ogden Nash at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ogden Nash at Wikimedia Commons- Ogden Nash's Collection Archived February 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine at the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin

- https://www.ibdb.com/broadway-cast-staff/ogden-nash-7942

- "American Poems: Ogden Nash". Includes a list of Ogden Nash poems.

- Blogden Nash fansite Includes Ogden Nash poems

- Vernon Duke's Musical Zoo YouTube

- poems by Ogden Nash set to music

- Kay McCracken Duke, mezzo-soprano

- David Berfield, pianist

- Information Please episode 1939.01.17 with panelists Hendrik Willem van Loon and Ogden Nash MP3

- https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0621790/

- Ogden Nash at Find a Grave