| Old Man of the Mountain | |

|---|---|

| Great Stone Face, The Profile | |

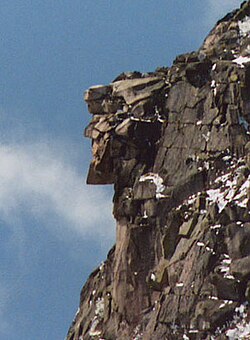

Old Man of the Mountain on April 26, 2003, seven days before the collapse | |

| |

| Type | Rock formation (former) |

| Location | Cannon Mountain, Franconia, New Hampshire, United States |

| Coordinates | 44°09′38″N 71°41′00″W / 44.1606203°N 71.6834169°W |

| Elevation | 3,130 feet (950 m) |

| Height | 40 feet (12 m) |

| Formed | ≈ 300 to 12,000 years ago |

| Demolished | May 3, 2003 (collapsed) |

The Old Man of the Mountain, also called the Great Stone Face and the Profile,[1][2] was a series of five granite cliff ledges on Cannon Mountain in Franconia, New Hampshire, United States, that appeared to be the jagged profile of a human face when viewed from the north. The rock formation, 1,200 feet (370 m) above Profile Lake, was 40 feet (12 m) tall and 25 feet (7.6 m) wide.

The Old Man of the Mountain is called "Stone Face" by the Abenaki and is a symbol within their culture.[3] It is also a symbol to the Mohawk people. The first written mention of the Old Man was in 1805. It became a landmark and a cultural icon for the state of New Hampshire, and has been featured as the Emblem of New Hampshire since 1945. It collapsed on May 3, 2003.[4] After its collapse, residents considered replacing it with a replica, but the idea was ultimately rejected. It remains a visual icon on the state's license plates and in other places.

History

[edit]

Summer, 1972 – Historical Marker:

"OLD MAN OF THE MOUNTAIN – 'The Great Stone Face" – 48' forehead to chin; 1200' above Profile Lake; 3200' above sea level; first seen by white men in 1805."

Franconia Notch is a U-shaped valley in the White Mountains that was shaped by glaciers. The Old Man formation was likely formed from freezing and thawing of water in cracks of the granite bedrock sometime after the retreat of glaciers 12,000 years ago.[5] The formation was first noted in the records of a Franconia surveying team around 1805. Francis Whitcomb and Luke Brooks, part of the surveying team, were the first two to record observing the Old Man.[5] The official state history says several groups of surveyors were working in the Franconia Notch area at the time and claimed credit for the discovery.

Indigenous legends

[edit]According to Abenaki legend, a human named Nis Kizos was born during an eclipse. He became a good leader and provider for his community. Nis Kizos was successful enough to attend a Kchi Mahadan, which was a great gathering of communities, to trade. Tarlo, a beautiful Iroquois woman, returned with him. They fell in love. Tarlo had to return to her birth village because its people had been struck by a sickness. Nis Kizos promised he would live at the top of the mountain. By day he would look out for her, and at night he would light a fire to guide her back. With winter fast approaching, the elders sent Nis Kizos's brother, Gezosa, to bring him back. He was unsuccessful because Nis Kizos maintained his promise. Tarlo died of sickness in her birth village. After the winter, Gezosa went back up the mountain to bring the news of Tarlo and retrieve Nis Kizos. He found no signs of the existence of Nis Kizos and was stricken with sadness. On his way back down the mountain he looked back and saw that Nis Kizos had become part of the mountain as a stone face to look after the land.

A modern addition to the Abenaki legend is that when Stone Face fell in 2003, he finally was re-united with Tarlo. The Great Circle was rejoined.[3]

Denise Ortakales published a children's book in 2005 called The Legend of the Old Man of the Mountain, which relates the Mohawk legend of the stone face. In the tale, Chief Pemigewassat loved a maiden named Minerwa of the Mohawk people, which brought peace between their tribes for a long time. When Minerwa went back home to visit her dying father, Chief Pemigewassat promised he would stay and wait for her to return. However, the Great Spirit claimed him during the winter, and his people buried him facing towards Minerwa to watch for her return. His face was immortalized in the stone as the stone face, forever waiting and watching.[6]

Post-colonial history

[edit]

The Old Man became famous across the United States largely because of statesman Daniel Webster, a New Hampshire native, who once wrote: "Men hang out their signs indicative of their respective trades; shoemakers hang out a gigantic shoe; jewelers a monster watch, and the dentist hangs out a gold tooth; but up in the Mountains of New Hampshire, God Almighty has hung out a sign to show that there He makes men."

The writer Nathaniel Hawthorne used the Old Man as inspiration for his 1850 short story "The Great Stone Face", in which he described the formation as "a work of Nature in her mood of majestic playfulness".

The profile has been New Hampshire's state emblem since 1945.[7] It was put on the state's license plates and state route signs, and on the back of New Hampshire's statehood quarter, popularly promoted as the only U.S. coin with a profile on both sides. Before the collapse, it could be seen from special viewing areas along Interstate 93 in Franconia Notch State Park, approximately 80 miles (130 km) north of the state's capital, Concord.

Collapse

[edit]

Freezing and thawing opened fissures in the Old Man's "forehead". By the 1920s, the crack was wide enough to be mended with chains, and in 1957 the state legislature passed a $25,000 appropriation for a more elaborate weatherproofing, using 20 tons of fast-drying cement, plastic covering and steel rods and turnbuckles, plus a concrete gutter to divert runoff from above. A team from the state highway and park divisions maintained the patchwork each summer.[8]

Nevertheless, the formation collapsed to the ground between midnight and 2 a.m. on May 3, 2003.[4] Dismay over the collapse was so great that people visited to pay tribute, with some leaving flowers.[9][10]

After the collapse

[edit]

Early after the collapse, many New Hampshire residents considered replacement with a replica. That idea was rejected by an official task force later in 2003 headed by former Governor Steve Merrill.[11]

In 2004, the state legislature considered, but did not accept, a proposal to change New Hampshire's state flag to include the profile.[12]

On the first anniversary of the collapse in May 2004, the Old Man of the Mountain Legacy Fund (OMMLF) began operating coin-operated viewfinders near the base of the cliff. When looking through them up at the cliff of Cannon Mountain one can see a "before" and "after" of how the Old Man of the Mountain used to appear.[4]

Seven years after the collapse, on June 24, 2010, the OMMLF, now the Friends of the Old Man of the Mountain, broke ground for the first phase of the state-sanctioned "Old Man of the Mountain Memorial" on a walkway along Profile Lake below Cannon Cliff. It consists of a viewing platform with "Steel Profilers", which, when aligned with the Cannon Cliff above, create what the profile looked like up on the cliff overlooking Franconia Notch. The project was overseen by Friends of the Old Man of the Mountain/Franconia Notch,[13] a committee that succeeded the Old Man of the Mountain Revitalization Task Force. The Legacy Fund is a private 501(c)(3) corporation with representatives from various state agencies and several private nonprofits.[14]

In 2013, the board called a halt to further fundraising. They announced their intention to spend what was left on minor improvements and dissolve the board.[11]

The memorial was completed in September 2020.[15]

Other proposals that were considered but rejected include:

- Architect Francis Treves envisioned a walk-in profile made of 250 panels of structural glass attached to tubular steel framework and concrete tower, connected by a tram, rim trail or tunnel through to the cliff wall at the original site. It won an American Institute of Architects Un-Built Project Award.[16][17][18]

- In 2009, Ken N. Gidge, a state representative from Nashua, proposed building a copper replica of the Old Man on level ground above the ledge at the original site where hiking trails already lead.[19]

Timeline of the Old Man

[edit]Details of the history of the Old Man of the Mountain include:[20]

- 17th millennium BC–6th millennium BC — New England underwent the Wisconsin glaciation, the most recent ice age. Glaciers covering New England and post-glacial erosion created the cliff which would subsequently erode into the Old Man of the Mountain at Franconia Notch.

- 9th millennium BC — Human beings begin to populate the area,[21] after which the Old Man is recognized and becomes the inspiration for stories and legends.

- 1805 — Francis Whitcomb and Luke Brooks, part of a Franconia surveying crew, were the first white settlers to record observing the Old Man, according to the official New Hampshire history.

- Early 1800s — American statesman Daniel Webster brought national attention to the profile in his writings.

- 1832 — Author Nathaniel Hawthorne visited the area.

- 1850 — Hawthorne published "The Great Stone Face", a short story inspired by his visit. The story's title became an alternative name for the formation.

- 1869 — President Ulysses S. Grant visited the formation.

- 1906 — The Reverend Guy Roberts of New Hampshire was the first to publicize signs of deterioration of the formation.[22]

- 1916 — New Hampshire Governor Rolland H. Spaulding began a concerted state effort to preserve the formation.

- 1926 — The formation appeared on all New Hampshire passenger, dealer, replacement, and sample license plates for this year.

- 1945 — The Old Man was made the New Hampshire State Emblem.[7]

- 1955 — President Dwight D. Eisenhower visited the profile as part of the Old Man's 150th "birthday" celebration.

- 1958 — Major repair work to the Old Man's forehead was undertaken as a result of a legislative appropriation the previous year.

- 1965 — Niels Nielsen, a state highway worker, became the unofficial guardian of the profile, in an effort to protect the formation from vandalism and the ravages of the weather.[23]

- 1974 — From 1974 to 1979, each license plate validation sticker had a likeness of the formation.

- 1976 — For the United States Bicentennial the formation was once again available on the state's license plate, but it cost an extra $5 and it could only be used as a front plate.

- 1986 — Vandalizing the Old Man was classified as a crime under the state criminal mischief law. Under the law (RSA 634:2 VI) it was a misdemeanor for any person to vandalize, deface or destroy any part of the Old Man, with a penalty of a fine of between $1,000 and $3,000 and restitution to the state for any damage caused.[24]

- 1987 — Nielsen was named the official caretaker of the Old Man by the state of New Hampshire. Beginning that year all passenger car license plates had a small image of the formation at the top. This practice continued through 1999. The license plates distributed after 1999 were redesigned to feature the Old Man of the Mountain much more prominently.

- 1988 — A 12-mile (19 km) stretch of Interstate 93 (which also runs jointly with U.S. Route 3 through the notch) opened below Cannon Mountain. The $56 million project, which took 30 years to build, was a compromise between the desire for a four-lane interstate and those who sought to limit the impact on the notch.

- 1991 — David Nielsen, son of Niels Nielsen, became the official caretaker of the Old Man.

- 2000 — The Old Man was featured on the state quarter of New Hampshire and became the graphic background on passenger car license plates.

- 2003 — The Old Man collapsed.[4]

- 2004 — Coin-operated viewfinders were installed to show how the Old Man looked before its collapse.[4]

- 2007 — Design of an Old Man of the Mountain memorial announced.

- 2010 — First phase of the state-sanctioned "Old Man of the Mountain Memorial" was unveiled.

- 2011 — Profiler Plaza was dedicated on June 12.

- 2020 — Memorial completed in September.[15]

- 2023 — State Representative Tim Cahill compared the collapse of the Old Man to 9/11 in debate over a bill to create a memorialization day for the Old Man; this comparison drew criticism.[25]

- 2023 — New Hampshire establishes May 7 as Old Man of the Mountain Day.[26][27]

See also

[edit]- List of rock formations that resemble human beings

- Mount Pemigewasset, another New Hampshire rock formation

- Pareidolia

- Cydonia, location of the "Face on Mars"

- Old Man of the Lake

- Profile Rock

References

[edit]- ^ Russell, Jenna (May 5, 2023). "New Hampshire's Old Man of the Mountain, 20 Years Gone, Still Bewitches - The rock formation collapsed in 2003, but it hasn't lost its hold on residents, who have passed on their affection to a new generation". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 5, 2023. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ "Franconia Notch". Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2008. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b "The Wobanadenok". Indigenous New Hampshire Collaborative Collective. December 6, 2018. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e New Hampshire Division of Parks and Recreation: Old Man of the Mountain Historic Site Accessed: August 14, 2012.

- ^ a b Linowes, Jonathan. "Old Man of the Mountain Legacy Fund: Geology of the Old Man of the Mountain". www.oldmanofthemountainlegacyfund.org. Archived from the original on May 27, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ "The Legend of the Old Man of the Mountain". The Free Library. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ a b New Hampshire Revised Statutes Annotated, Title I, Section 3:1

- ^ Daniel Ford, The Country Northward (1976), p. 52.

- ^ "Today is the 15th anniversary of Old Man of the Mountain's collapse". The Berlin Daily Sun. May 1, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2019.

- ^ Colquhoun, Laura (May 11, 2003). "Hundreds Gather for Goodbyes". New Hampshire Union Leader. p. A1.

- ^ a b Merrill, Steve. "Old Man of the Mountain Memorial". Live Free or Die Alliance. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ^ J. Dennis Robinson (February 27, 2004). "Save the Seal, Keep the Ship". SeacoastNH.com. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- ^ Lorna Colquhoun (June 25, 2010). "Old Man's profile makes return". New Hampshire Union Leader. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- ^ "Old Man of the Mountain Legacy Fund". Old Man of the Mountain Legacy Fund. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- ^ a b AP: "Old Man memorial hopes for more volunteers", September 14, 2020

- ^ Garry Rayno (April 24, 2009). "Designer: Replace Old Man with walk-in glass replica". New Hampshire Union-Leader. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- ^ "Redefinition of the Old Man of the Mountain". Francis Treves, AIA. April 26, 2010. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ^ Dave. "Replacing the Old Man of the Mountain – with information from the Architect". Towns and Trails. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ Edge Mugga (January 7, 2009). "New Hampshire Proposal to Rebuild the Old Man of the Mountain: HB 192". Edge-On Blog. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- ^ "Old Man of the Mountain Legacy Fund: Historical Timeline". Archived from the original on 2015-12-11. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- ^ "Native American Heritage". New Hampshire Folk Life. State of New Hampshire. Retrieved June 24, 2023.

- ^ Speck, Jerel (June 20, 2019). Clark, Susan (ed.). "The men who went to great heights to save the Old Man". Neighborhood News. Vol. 1, no. 33. Manchester, New Hampshire: Neighborhood News, Inc. p. 11.

- ^ "Old Man Timeline". Old Man of the Mountain Legacy Fund. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ New Hampshire Revised Statutes Annotated, Title LXII, Section 634:2

- ^ CBSBoston.com Staff (March 22, 2023). "NH rep likens Old Man of the Mountain collapse to Twin Towers falling on 9/11". CBS Boston. CBS Broadcasting Inc. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- ^ Landrigan, Kevin (May 3, 2023). "Old Man of the Mountain gets a day". New Hampshire Union Leader. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ New Hampshire Revised Statutes Annotated, Title I, Section 4:13-dd

Further reading

[edit]- DeCosta-Klipa, Nik (May 3, 2018). "An oral history of the fall of the Old Man of the Mountain". Boston.com. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

External links

[edit]- The Day the Old Man Fell via YouTube

- The Old Man of the Mountain Legacy Fund

- NH State Parks — An end is just a new beginning

- 19th-century paintings of the Old Man of the Mountain

- Photos from atop the Old Man of the Mountain after the collapse

- The Evolution of Cannon Cliff project (Dartmouth College et al.)

- The project's The Old Man of the Mountain in 3D StoryMap