In Greek mythology, Orthrus (‹See Tfd›Greek: Ὄρθρος, Orthros) or Orthus (‹See Tfd›Greek: Ὄρθος, Orthos) was, according to the mythographer Apollodorus, a two-headed dog who guarded Geryon's cattle and was killed by Heracles.[1] He was the offspring of the monsters Echidna and Typhon, and the brother of Cerberus, who was also a multi-headed guard dog.[2]

Name

[edit]His name is given as either "Orthrus" (Ὄρθρος) or "Orthus" (Ὄρθος). For example, Hesiod, the oldest source, calls the hound "Orthus", while Apollodorus calls him "Orthrus".[3]

Mythology

[edit]According to Hesiod, Orthrus was the father of the Sphinx and the Nemean Lion, though whom Hesiod meant as the mother, whether it is Orthrus' own mother Echidna, the Chimera, or Ceto, is unclear.[4]

Orthrus and his master Eurytion were charged with guarding the three-headed, or three-bodied giant Geryon's herd of red cattle in the "sunset" land of Erytheia ("red one"), an island in the far west of the Mediterranean.[5] Heracles killed Orthrus, and later slew Eurytion and Geryon before taking the red cattle to complete his tenth labor. According to Apollodorus, Heracles killed Orthrus with his club, although in art Orthrus is sometimes depicted pierced by arrows.[6]

The poet Pindar refers to the "hounds of Geryon" trembling before Heracles.[7] Pindar's use of the plural "hounds" in connection with Geryon is unique.[8] He may have used the plural because Orthus had multiple heads, or perhaps because he knew a tradition in which Geryon had more than one dog.[9]

In art

[edit]

Depictions of Orthrus in art are rare, and always in connection with the theft of Geryon's cattle by Heracles. He is usually shown dead or dying, sometimes pierced by one or more arrows.[10]

The earliest depiction of Orthrus is found on a late seventh-century bronze horse pectoral from Samos (Samos B2518).[11] It shows a two-headed Orthrus, with an arrow protruding from one of his heads, crouching at the feet, and in front of Geryon. Orthrus is facing Heracles, who stands to the left, wearing his characteristic lion-skin, fighting Geryon to the right.

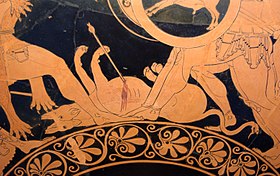

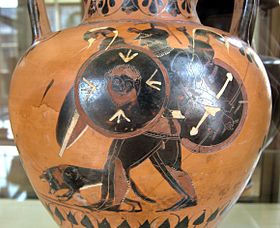

A red-figure cup by Euphronios from Vulci c. 550–500 BC (Munich 2620) shows a two-headed Orthrus lying belly-up, with an arrow piercing his chest, and his snake tail still writhing behind him.[12] Heracles is on the left, wearing his lion-skin, fighting a three-bodied Geryon to the right. An Attic black-figure neck amphora, by the Swing Painter c. 550–500 BC (Cab. Med. 223), shows a two-headed Orthrus, at the feet of a three-bodied Geryon, with two arrows protruding through one of his heads, and a dog tail.[13]

According to Apollodorus, Orthrus had two heads; however, in art, the number varies.[14] As in the Samos pectoral, Euphronios' cup, and the Swing Painter's, amphora, Orthrus is usually depicted with two heads,[15] although, from the mid sixth century, he is sometimes depicted with only one head,[16] while one early fifth century BC Cypriot stone relief gives him three heads, á la Cerberus.[17]

The Euphronios cup, and the stone relief depict Orthrus, like Cerberus, with a snake tail, though usually he is shown with a dog tail, as in the Swing Painter's amphora.[18]

Similarities with Cerberus

[edit]Orthrus bears a close resemblance to Cerberus, the hound of Hades. The classical scholar Arthur Bernard Cook called Orthrus Cerberus' "doublet".[19] According to Hesiod, Cerberus, like Orthrus was the offspring of Echidna and Typhon. And like Orthrus, Cerberus was multi-headed. The earliest accounts gave Cerberus fifty,[20] or even one hundred heads,[21] though in literature three heads for Cerberus became the standard.[22] However, in art, often only two heads for Cerberus are shown.[23] Cerberus was also usually depicted with a snake tail, just as Orthrus was sometimes. Both became guard dogs, with Cerberus guarding the gates of Hades, and both were overcome by Heracles in one of his labours.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Apollodorus, 2.5.10.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 306–312; Apollodorus, 2.5.10. Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica (or Fall of Troy) 6.249 ff. (pp. 272–273) has Cerberus as the offspring of Echidna and Typhon, and Orthrus as his brother.

- ^ Hesiod Theogony 293, 309, 327; Apollodorus, 2.5.10. For the form of the name used in other sources see West, pp. 248–249 line 293 Ὄρθον; Frazer's note 4 to Apollodorus, 2.5.10.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 326–329. The referent of "she" in line 326 of the Theogony is uncertain, see Clay, p.159, with n. 34.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 287–294, 979–983; Apollodorus, 2.5.10; Gantz, pp. 402–408.

- ^ Woodford, p. 106.

- ^ Pindar, Isthmian 1.13–15.

- ^ Race, p. 139 n. 3.

- ^ Bury, pp. 12–13 n. 13; Fennell, p. 129 n. 13.

- ^ Woodford, p, 106; Ogden, p. 114.

- ^ Woodford, p. 106; Stafford, pp. 43–44; Ogden, p. 114 n. 256; LIMC Orthros I 19.

- ^ Beazley Archive 200080; LIMC Orthros I 14; Schefold, pp. 126–128, figs. 147, 148; Stafford, p. 45; Gantz, p. 403.

- ^ Beazley Archive 301557; LIMC Orthros I 12; Ogden, p. 114 n. 257; Gantz, p. 403.

- ^ Apollodorus, 2.5.10; Cook, p. 410; Ogden, p. 114.

- ^ Woodford, p. 106; Ogden, p. 114, with n. 256; LIMC Orthros I 19. Other two-headed examples include: LIMC Orthros I 6–18, 20.

- ^ Ogden, p. 114, with n. 256. For an example of a one-headed Orthrus see: British Museum B194 (Bristish Museum 1836,0224.103; Beazley Archive 310316; LIMC Orthros I 2). Other one-headed examples include: LIMC Orthros I 1, 3–5.

- ^ LIMC Orthros I 21; Metropolitan Museum of Art 74.51.2853; Mertens, p. 78, fig. 31.

- ^ Ogden, Ogden, p. 114, with n. 256.

- ^ Cook, p. 410.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 311–312.

- ^ Pindar fragment F249a/b SM, from a lost Pindar poem on Heracles in the underworld, according to a scholia on the Iliad, Gantz p. 22; Ogden, p. 105, with n. 182.

- ^ Ogden, pp. 105–106, with n. 183.

- ^ Ogden, p. 106, wonders whether "such images salute or establish a tradition of a two-headed Cerberus, or are we to imagine a third head concealed behind the two that can be seen?"

References

[edit]- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Bury, J. B. The Isthmian Odes of Pindar, Macmillan, 1892.

- Cook, Arthur Bernard, Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, Volume III: Zeus God of the Dark Sky (Earthquakes, Clouds, Wind, Dew, Rain, Meteorites), Part I: Text and Notes, Cambridge University Press 1940. Internet Archive

- Clay, Jenny Strauss, Hesiod's Cosmos, Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-521-82392-0.

- Fennel, Charles Augustus Maude, Pindar: The Nemean and Isthmian Odes : with Notes Explanatory and Critical, Intro., and Introductory Essays, University Press, 1883.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Mertens, Joan R., How to Read Vases, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010, ISBN 9781588394040.

- Ogden, Daniel, Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds, Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 9780199557325.

- Pindar, Odes, Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1990. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Race, William H., Nemean Odes. Isthmian Odes. Fragments, Edited and translated by William H. Race. Loeb Classical Library 485. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997, revised 2012. ISBN 978-0-674-99534-5. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Schefold, Karl, Luca Giuliani, Gods and Heroes in Late Archaic Greek Art, Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 9780521327183

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Quintus Smyrnaeus: The Fall of Troy, Translator: A.S. Way; Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 1913. Internet Archive

- Smith, William; Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). "Orthrus"

- Stafford, Emma, Herakles, Routledge, 2013. ISBN 9781136519277.

- West, M. L. (1966), Hesiod: Theogony, Oxford University Press.

- Woodford, Susan, "Othros I", in Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC) VII.1. Artemis Verlag, Zürich and Munich, 1994. ISBN 3760887511. pp. 105–107.

External links

[edit] Media related to Orthrus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Orthrus at Wikimedia Commons- Theoi Project - Kyon Orthros