| Osteoarthritis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Arthrosis, osteoarthrosis, degenerative arthritis, degenerative joint disease |

| |

| The formation of hard knobs at the middle finger joints (known as Bouchard's nodes) and at the farthest joints of the fingers (known as Heberden's nodes) is a common feature of osteoarthritis in the hands. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology, orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Joint pain, stiffness, joint swelling, decreased range of motion[1] |

| Usual onset | Over years[1] |

| Causes | Connective tissue disease, previous joint injury, abnormal joint or limb development, inherited factors[1][2] |

| Risk factors | Overweight, legs of different lengths, job with high levels of joint stress[1][2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, supported by other testing[1] |

| Treatment | Exercise, efforts to decrease joint stress, support groups, pain medications, joint replacement[1][2][3] |

| Frequency | 237 million / 3.3% (2015)[4] |

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a type of degenerative joint disease that results from breakdown of joint cartilage and underlying bone.[5][6] It is believed to be the fourth leading cause of disability in the world, affecting 1 in 7 adults in the United States alone.[7] The most common symptoms are joint pain and stiffness.[1] Usually the symptoms progress slowly over years.[1] Other symptoms may include joint swelling, decreased range of motion, and, when the back is affected, weakness or numbness of the arms and legs.[1] The most commonly involved joints are the two near the ends of the fingers and the joint at the base of the thumbs, the knee and hip joints, and the joints of the neck and lower back.[1] The symptoms can interfere with work and normal daily activities.[1] Unlike some other types of arthritis, only the joints, not internal organs, are affected.[1]

Causes include previous joint injury, abnormal joint or limb development, and inherited factors.[1][2] Risk is greater in those who are overweight, have legs of different lengths, or have jobs that result in high levels of joint stress.[1][2][8] Osteoarthritis is believed to be caused by mechanical stress on the joint and low grade inflammatory processes.[9] It develops as cartilage is lost and the underlying bone becomes affected.[1] As pain may make it difficult to exercise, muscle loss may occur.[2][10] Diagnosis is typically based on signs and symptoms, with medical imaging and other tests used to support or rule out other problems.[1] In contrast to rheumatoid arthritis, in osteoarthritis the joints do not become hot or red.[1]

Treatment includes exercise, decreasing joint stress such as by rest or use of a cane, support groups, and pain medications.[1][3] Weight loss may help in those who are overweight.[1] Pain medications may include paracetamol (acetaminophen) as well as NSAIDs such as naproxen or ibuprofen.[1] Long-term opioid use is not recommended due to lack of information on benefits as well as risks of addiction and other side effects.[1][3] Joint replacement surgery may be an option if there is ongoing disability despite other treatments.[2] An artificial joint typically lasts 10 to 15 years.[11]

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis, affecting about 237 million people or 3.3% of the world's population, as of 2015.[4][12] It becomes more common as people age.[1] Among those over 60 years old, about 10% of males and 18% of females are affected.[2] Osteoarthritis is the cause of about 2% of years lived with disability.[12]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

The main symptom is pain, causing loss of ability and often stiffness. The pain is typically made worse by prolonged activity and relieved by rest. Stiffness is most common in the morning, and typically lasts less than thirty minutes after beginning daily activities, but may return after periods of inactivity. Osteoarthritis can cause a crackling noise (called "crepitus") when the affected joint is moved, especially shoulder and knee joint. A person may also complain of joint locking and joint instability. These symptoms would affect their daily activities due to pain and stiffness.[13] Some people report increased pain associated with cold temperature, high humidity, or a drop in barometric pressure, but studies have had mixed results.[14]

Osteoarthritis commonly affects the hands, feet, spine, and the large weight-bearing joints, such as the hips and knees, although in theory, any joint in the body can be affected. As osteoarthritis progresses, movement patterns (such as gait), are typically affected.[1] Osteoarthritis is the most common cause of a joint effusion of the knee.[15]

In smaller joints, such as at the fingers, hard bony enlargements, called Heberden's nodes (on the distal interphalangeal joints) or Bouchard's nodes (on the proximal interphalangeal joints), may form, and though they are not necessarily painful, they do limit the movement of the fingers significantly. Osteoarthritis of the toes may be a factor causing formation of bunions,[16] rendering them red or swollen.

Causes

[edit]Damage from mechanical stress with insufficient self repair by joints is believed to be the primary cause of osteoarthritis.[17] Sources of this stress may include misalignments of bones caused by congenital or pathogenic causes; mechanical injury; excess body weight; loss of strength in the muscles supporting a joint; and impairment of peripheral nerves, leading to sudden or uncoordinated movements.[17] The risk of osteoarthritis increases with aging, history of joint injury, or family history of osteoarthritis.[18] However exercise, including running in the absence of injury, has not been found to increase the risk of knee osteoarthritis.[19][20] Nor has cracking one's knuckles been found to play a role.[21]

Primary

[edit]The development of osteoarthritis is correlated with a history of previous joint injury and with obesity, especially with respect to knees.[22] Changes in sex hormone levels may play a role in the development of osteoarthritis, as it is more prevalent among post-menopausal women than among men of the same age.[1][23] Conflicting evidence exists for the differences in hip and knee osteoarthritis in African Americans and Caucasians.[24]

Occupational

[edit]Increased risk of developing knee and hip osteoarthritis was found among those who work with manual handling (e.g. lifting), have physically demanding work, walk at work, and have climbing tasks at work (e.g. climb stairs or ladders).[8] With hip osteoarthritis, in particular, increased risk of development over time was found among those who work in bent or twisted positions.[8] For knee osteoarthritis, in particular, increased risk was found among those who work in a kneeling or squatting position, experience heavy lifting in combination with a kneeling or squatting posture, and work standing up.[8] Women and men have similar occupational risks for the development of osteoarthritis.[8]

Secondary

[edit]This type of osteoarthritis is caused by other factors but the resulting pathology is the same as for primary osteoarthritis:

- Alkaptonuria[25]

- Congenital disorders of joints[26][27]

- Diabetes doubles the risk of having a joint replacement due to osteoarthritis and people with diabetes have joint replacements at a younger age than those without diabetes.[28]

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome[29]

- Hemochromatosis and Wilson's disease[30]

- Inflammatory diseases (such as Perthes' disease), (Lyme disease), and all chronic forms of arthritis (e.g., costochondritis, gout, and rheumatoid arthritis). In gout, uric acid crystals cause the cartilage to degenerate at a faster pace.

- Injury to joints or ligaments (such as the ACL) as a result of an accident or orthopedic operations.

- Ligamentous deterioration or instability may be a factor.

- Marfan syndrome[31]

- Obesity[32]

- Joint infection[33][34][35]

Pathophysiology

[edit]While osteoarthritis is a degenerative joint disease that may cause gross cartilage loss and morphological damage to other joint tissues, more subtle biochemical changes occur in the earliest stages of osteoarthritis progression. The water content of healthy cartilage is finely balanced by compressive force driving water out and hydrostatic and osmotic pressure drawing water in.[37][38] Collagen fibres exert the compressive force, whereas the Gibbs–Donnan effect and cartilage proteoglycans create osmotic pressure which tends to draw water in.[38]

However, during onset of osteoarthritis, the collagen matrix becomes more disorganized and there is a decrease in proteoglycan content within cartilage. The breakdown of collagen fibers results in a net increase in water content.[39][40][41][42][43] This increase occurs because whilst there is an overall loss of proteoglycans (and thus a decreased osmotic pull),[40][44] it is outweighed by a loss of collagen.[38][44]

Other structures within the joint can also be affected.[45] The ligaments within the joint become thickened and fibrotic, and the menisci can become damaged and wear away.[46] Menisci can be completely absent by the time a person undergoes a joint replacement. New bone outgrowths, called "spurs" or osteophytes, can form on the margins of the joints, possibly in an attempt to improve the congruence of the articular cartilage surfaces in the absence of the menisci. The subchondral bone volume increases and becomes less mineralized (hypo mineralization).[47] All these changes can cause problems functioning. The pain in an osteoarthritic joint has been related to thickened synovium[48] and to subchondral bone lesions.[49]

Diagnosis

[edit]| Type | WBC (per mm3) | % neutrophils | Viscosity | Appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | <200 | 0 | High | Transparent |

| Osteoarthritis | <5000 | <25 | High | Clear yellow |

| Trauma | <10,000 | <50 | Variable | Bloody |

| Inflammatory | 2,000–50,000 | 50–80 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Septic arthritis | >50,000 | >75 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Gonorrhea | ~10,000 | 60 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Tuberculosis | ~20,000 | 70 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Inflammatory: Arthritis, gout, rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatic fever | ||||

Diagnosis is made with reasonable certainty based on history and clinical examination.[52][53] X-rays may confirm the diagnosis. The typical changes seen on X-ray include: joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis (increased bone formation around the joint), subchondral cyst formation, and osteophytes.[54] Plain films may not correlate with the findings on physical examination or with the degree of pain.[55]

In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology, using data from a multi-center study, developed a set of criteria for the diagnosis of hand osteoarthritis based on hard tissue enlargement and swelling of certain joints.[56] These criteria were found to be 92% sensitive and 98% specific for hand osteoarthritis versus other entities such as rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthropathies.[57]

-

Severe osteoarthritis and osteopenia of the carpal joint and 1st carpometacarpal joint

-

MRI of osteoarthritis in the knee, with characteristic narrowing of the joint space

-

Primary osteoarthritis of the left knee. Note the osteophytes, narrowing of the joint space (arrow), and increased subchondral bone density (arrow).

-

Damaged cartilage from sows. (a) cartilage erosion (b)cartilage ulceration (c)cartilage repair (d)osteophyte (bone spur) formation.

-

Histopathology of osteoarthrosis of a knee joint in an elderly female

-

Histopathology of osteoarthrosis of a knee joint in an elderly female

-

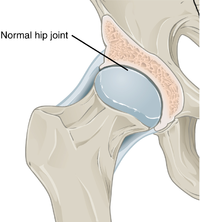

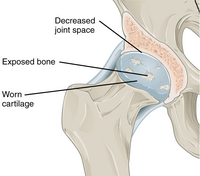

In a healthy joint, the ends of bones are encased in smooth cartilage. Together, they are protected by a joint capsule lined with a synovial membrane that produces synovial fluid. The capsule and fluid protect the cartilage, muscles, and connective tissues.

-

With osteoarthritis, the cartilage becomes worn away. Spurs grow out from the edge of the bone, and synovial fluid increases. Altogether, the joint feels stiff and sore.

-

Osteoarthritis

-

Bone (left) and clinical (right) changes of the hand in osteoarthritis

Classification

[edit]A number of classification systems are used for gradation of osteoarthritis:

- WOMAC scale, taking into account pain, stiffness and functional limitation.[58]

- Kellgren-Lawrence grading scale for osteoarthritis of the knee. It uses only projectional radiography features.

- Tönnis classification for osteoarthritis of the hip joint, also using only projectional radiography features.[59]

Both primary generalized nodal osteoarthritis and erosive osteoarthritis (EOA, also called inflammatory osteoarthritis) are sub-sets of primary osteoarthritis. EOA is a much less common, and more aggressive inflammatory form of osteoarthritis which often affects the distal interphalangeal joints of the hand and has characteristic articular erosive changes on X-ray.[60]

Management

[edit]

Lifestyle modification (such as weight loss and exercise) and pain medications are the mainstays of treatment. Acetaminophen (also known as paracetamol) is recommended first line, with NSAIDs being used as add-on therapy only if pain relief is not sufficient.[61][62] Medications that alter the course of the disease have not been found as of 2018.[63] For overweight people, weight loss may help relieve pain due to hip arthritis.[64] Recommendations include modification of risk factors through targeted interventions including 1) obesity and overweight, 2) physical activity, 3) dietary exposures, 4) comorbidities, 5) biomechanical factors, 6) occupational factors.[65]

Successful management of the condition is often made more difficult by differing priorities and poor communication between clinicians and people with osteoarthritis. Realistic treatment goals can be achieved by developing a shared understanding of the condition, actively listening to patient concerns, avoiding medical jargon and tailoring treatment plans to the patient's needs.[66][67]

Exercise

[edit]Weight loss and exercise provide long-term treatment and are advocated in people with osteoarthritis.[68] Weight loss and exercise are the most safe and effective long-term treatments, in contrast to short-term treatments which usually have risk of long-term harm.[69]

High impact exercise can increase the risk of joint injury, whereas low or moderate impact exercise, such as walking or swimming, is safer for people with osteoarthritis.[68] A study has suggested that an increase in blood calcium levels had a positive impact on osteoarthritis. An adequate dietary calcium intake and regular weight-bearing exercise can increase calcium levels and is helpful in preventing osteoarthritis in the general population.[citation needed] There is also a weak protective effect factor of LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol. However, this is not recommended since an increase in LDL has an increased chance of cardiovascular comorbidities.[70]

Moderate exercise may be beneficial with respect to pain and function in those with osteoarthritis of the knee and hip.[71][72][73] These exercises should occur at least three times per week, under supervision, and focused on specific forms of exercise found to be most beneficial for this form of osteoarthritis.[74]

While some evidence supports certain physical therapies, evidence for a combined program is limited.[75] Providing clear advice, making exercises enjoyable, and reassuring people about the importance of doing exercises may lead to greater benefit and more participation.[73] Some evidence suggests that supervised exercise therapy may improve exercise adherence,[76] although for knee osteoarthritis supervised exercise has shown the best results.[74]

Physical measures

[edit]There is not enough evidence to determine the effectiveness of massage therapy.[77] The evidence for manual therapy is inconclusive.[78] A 2015 review indicated that aquatic therapy is safe, effective, and can be an adjunct therapy for knee osteoarthritis.[79]

Functional, gait, and balance training have been recommended to address impairments of position sense, balance, and strength in individuals with lower extremity arthritis, as these can contribute to a higher rate of falls in older individuals.[80][81] For people with hand osteoarthritis, exercises may provide small benefits for improving hand function, reducing pain, and relieving finger joint stiffness.[82]

A study showed that there is low quality evidence that weak knee extensor muscle increased the chances of knee osteoarthritis. Strengthening of the knee extensors could possibly prevent knee osteoarthritis.[83]

Lateral wedge insoles and neutral insoles do not appear to be useful in osteoarthritis of the knee.[84][85][86] Knee braces may help[87] but their usefulness has also been disputed.[86] For pain management, heat can be used to relieve stiffness, and cold can relieve muscle spasms and pain.[88] Among people with hip and knee osteoarthritis, exercise in water may reduce pain and disability, and increase quality of life in the short term.[89] Also therapeutic exercise programs such as aerobics and walking reduce pain and improve physical functioning for up to 6 months after the end of the program for people with knee osteoarthritis.[90] In a study conducted over a period of 2 years on a group of individuals, a research team found that for every additional 1,000 steps per day, there was a 16% reduction in functional limitations in cases of knee osteoarthritis.[91] Hydrotherapy might also be an advantage on the management of pain, disability and quality of life reported by people with osteoarthritis.[92]

Thermotherapy

[edit]A 2003 Cochrane review of 7 studies between 1969 and 1999 found ice massage to be of significant benefit in improving range of motion and function, though not necessarily relief of pain.[93] Cold packs could decrease swelling, but hot packs had no effect on swelling.[93] Heat therapy could increase circulation, thereby reducing pain and stiffness, but with risk of inflammation and edema.[93]

Medication

[edit]| Treatment recommendations by risk factors | ||

|---|---|---|

| GI risk | CVD risk | Option |

| Low | Low | NSAID, or paracetamol[94] |

| Moderate | Low | Paracetamol, or low dose NSAID with antacid[94] |

| Low | Moderate | Paracetamol, or low dose aspirin with an antacid[94] |

| Moderate | Moderate | Low dose paracetamol, aspirin, and antacid. Monitoring for abdominal pain or black stool.[94] |

By mouth

[edit]The pain medication paracetamol (acetaminophen) is the first line treatment for osteoarthritis.[61][95] Pain relief does not differ according to dosage.[62] However, a 2015 review found acetaminophen to have only a small short-term benefit with some concerns on abnormal results for liver function test.[96] For mild to moderate symptoms effectiveness of acetaminophen is similar to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as naproxen, though for more severe symptoms NSAIDs may be more effective.[61] NSAIDs are associated with greater side effects such as gastrointestinal bleeding.[61]

Another class of NSAIDs, COX-2 selective inhibitors (such as celecoxib) are equally effective when compared to nonselective NSAIDs, and have lower rates of adverse gastrointestinal effects, but higher rates of cardiovascular disease such as myocardial infarction.[97] They are also more expensive than non-specific NSAIDs.[98] Benefits and risks vary in individuals and need consideration when making treatment decisions,[99] and further unbiased research comparing NSAIDS and COX-2 selective inhibitors is needed.[100] NSAIDS applied topically are effective for a small number of people.[101] The COX-2 selective inhibitor rofecoxib was removed from the market in 2004, as cardiovascular events were associated with long term use.[102]

Education is helpful in self-management of arthritis, and can provide coping methods leading to about 20% more pain relief when compared to NSAIDs alone.[64]

Failure to achieve desired pain relief in osteoarthritis after two weeks should trigger reassessment of dosage and pain medication.[103] Opioids by mouth, including both weak opioids such as tramadol and stronger opioids, are also often prescribed. Their appropriateness is uncertain, and opioids are often recommended only when first line therapies have failed or are contraindicated.[3][104] This is due to their small benefit and relatively large risk of side effects.[105][106] The use of tramadol likely does not improve pain or physical function and likely increases the incidence of adverse side effects.[106] Oral steroids are not recommended in the treatment of osteoarthritis.[95]

Use of the antibiotic doxycycline orally for treating osteoarthritis is not associated with clinical improvements in function or joint pain.[107] Any small benefit related to the potential for doxycycline therapy to address the narrowing of the joint space is not clear, and any benefit is outweighed by the potential harm from side effects.[107]

A 2018 meta-analysis found that oral collagen supplementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis reduces stiffness but does not improve pain and functional limitation.[108]

Topical

[edit]There are several NSAIDs available for topical use, including diclofenac. A Cochrane review from 2016 concluded that reasonably reliable evidence is available only for use of topical diclofenac and ketoprofen in people aged over 40 years with painful knee arthritis.[101] Transdermal opioid pain medications are not typically recommended in the treatment of osteoarthritis.[105] The use of topical capsaicin to treat osteoarthritis is controversial, as some reviews found benefit[109][110] while others did not.[111]

Joint injections

[edit]

Use of analgesia, intra-articular cortisone injection and consideration of hyaluronic acids and platelet-rich plasma are recommended for pain relief in people with knee osteoarthritis.[113]

Local drug delivery by intra-articular injection may be more effective and safer in terms of increased bioavailability, less systemic exposure and reduced adverse events.[114] Several intra-articular medications for symptomatic treatment are available on the market as follows.[115]

Steroids

[edit]Joint injection of glucocorticoids (such as hydrocortisone) leads to short-term pain relief that may last between a few weeks and a few months.[116] A 2015 Cochrane review found that intra-articular corticosteroid injections of the knee did not benefit quality of life and had no effect on knee joint space; clinical effects one to six weeks after injection could not be determined clearly due to poor study quality.[117] Another 2015 study reported negative effects of intra-articular corticosteroid injections at higher doses,[118] and a 2017 trial showed reduction in cartilage thickness with intra-articular triamcinolone every 12 weeks for 2 years compared to placebo.[119] A 2018 study found that intra-articular triamcinolone is associated with an increase in intraocular pressure.[120]

Hyaluronic acid

[edit]Injections of hyaluronic acid have not produced improvement compared to placebo for knee arthritis,[121][122] but did increase risk of further pain.[121] In ankle osteoarthritis, evidence is unclear.[123]

Platelet-rich plasma

[edit]The effectiveness of injections of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is unclear; there are suggestions that such injections improve function but not pain, and are associated with increased risk.[vague][124][125] A 2014 Cochrane review of studies involving PRP found the evidence to be insufficient.[126]

Radiosynoviorthesis

[edit]Injection of beta particle-emitting radioisotopes (called radiosynoviorthesis) is used for the local treatment of inflammatory joint conditions.[127]

Radiotherapy

[edit]Low-dose radiotherapy has been shown to improve pain and mobility of affected joints, primarily in extremities. It is approximately 70-90% effective, with minimal side effects.[128]

Surgery

[edit]Bone fusion

[edit]Arthrodesis (fusion) of the bones may be an option in some types of osteoarthritis. An example is ankle osteoarthritis, in which ankle fusion is considered to be the gold standard treatment in end-stage cases.[129]

Joint replacement

[edit]If the impact of symptoms of osteoarthritis on quality of life is significant and more conservative management is ineffective, joint replacement surgery or resurfacing may be recommended. Evidence supports joint replacement for both knees and hips as it is both clinically effective[130][131] and cost-effective.[132][133] People who underwent total knee replacement had improved SF-12 quality of life scores, were feeling better compared to those who did not have surgery, and may have short- and long-term benefits for quality of life in terms of pain and function.[134][135] The beneficial effects of these surgeries may be time-limited due to various environmental factors, comorbidities, and pain in other regions of the body.[136]

For people who have shoulder osteoarthritis and do not respond to medications, surgical options include a shoulder hemiarthroplasty (replacing a part of the joint), and total shoulder arthroplasty (replacing the joint).[137]

Biological joint replacement involves replacing the diseased tissues with new ones. This can either be from the person (autograft) or from a donor (allograft).[138] People undergoing a joint transplant (osteochondral allograft) do not need to take immunosuppressants as bone and cartilage tissues have limited immune responses.[139] Autologous articular cartilage transfer from a non-weight-bearing area to the damaged area, called osteochondral autograft transfer system, is one possible procedure that is being studied.[140] When the missing cartilage is a focal defect, autologous chondrocyte implantation is also an option.[141]

Shoulder replacement

[edit]For those with osteoarthritis in the shoulder, a complete shoulder replacement is sometimes suggested to improve pain and function.[142] Demand for this treatment is expected to increase by 750% by the year 2030.[142] There are different options for shoulder replacement surgeries, however, there is a lack of evidence in the form of high-quality randomized controlled trials, to determine which type of shoulder replacement surgery is most effective in different situations, what are the risks involved with different approaches, or how the procedure compares to other treatment options.[142][143] There is some low-quality evidence that indicates that when comparing total shoulder arthroplasty over hemiarthroplasty, no large clinical benefit was detected in the short term.[143] It is not clear if the risk of harm differs between total shoulder arthroplasty or a hemiarthroplasty approach.[143]

Other surgical options

[edit]Osteotomy may be useful in people with knee osteoarthritis, but has not been well studied and it is unclear whether it is more effective than non-surgical treatments or other types of surgery.[144][145] Arthroscopic surgery is largely not recommended, as it does not improve outcomes in knee osteoarthritis,[146][147] and may result in harm.[148] It is unclear whether surgery is beneficial in people with mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis.[145]

Unverified treatments

[edit]Glucosamine and chondroitin

[edit]The effectiveness of glucosamine is controversial.[149] Reviews have found it to be equal to[150][151] or slightly better than placebo.[152][153] A difference may exist between glucosamine sulfate and glucosamine hydrochloride, with glucosamine sulfate showing a benefit and glucosamine hydrochloride not.[154] The evidence for glucosamine sulfate having an effect on osteoarthritis progression is somewhat unclear and if present likely modest.[155] The Osteoarthritis Research Society International recommends that glucosamine be discontinued if no effect is observed after six months[156] and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence no longer recommends its use.[10] Despite the difficulty in determining the efficacy of glucosamine, it remains a treatment option.[157] The European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) recommends glucosamine sulfate and chondroitin sulfate for knee osteoarthritis.[158] Its use as a therapy for osteoarthritis is usually safe.[157][159]

A 2015 Cochrane review of clinical trials of chondroitin found that most were of low quality, but that there was some evidence of short-term improvement in pain and few side effects; it does not appear to improve or maintain the health of affected joints.[160]

Supplements

[edit]Avocado–soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) is an extract made from avocado oil and soybean oil[161] sold under many brand names worldwide as a dietary supplement[162] and as a prescription drug in France.[163] A 2014 Cochrane review found that while ASU might help relieve pain in the short term for some people with osteoarthritis, it does not appear to improve or maintain the health of affected joints.[161] The review noted a high-quality, two-year clinical trial comparing ASU to chondroitin – which has uncertain efficacy in osteoarthritis – with no difference between the two agents.[161] The review also found there is insufficient evidence of ASU safety.[161]

A few high-quality studies of Boswellia serrata show consistent, but small, improvements in pain and function.[161] Curcumin,[164] phytodolor,[109] and s-adenosyl methionine (SAMe)[109][77] may be effective in improving pain. A 2009 Cochrane review recommended against the routine use of SAMe, as there has not been sufficient high-quality clinical research to prove its effect.[165] A 2021 review found that hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) had no benefit in reducing pain and improving physical function in hand or knee osteoarthritis, and the off-label use of HCQ for people with osteoarthritis should be discouraged.[166] There is no evidence for the use of colchicine for treating the pain of hand or knee arthritis.[167]

There is limited evidence to support the use of hyaluronan,[168] methylsulfonylmethane,[109] rose hip,[109] capsaicin,[109] or vitamin D.[109][169]

Acupuncture and other interventions

[edit]While acupuncture leads to improvements in pain relief, this improvement is small and may be of questionable importance.[170] Waiting list–controlled trials for peripheral joint osteoarthritis do show clinically relevant benefits, but these may be due to placebo effects.[171][172] Acupuncture does not seem to produce long-term benefits.[173]

Electrostimulation techniques such as TENS have been used for twenty years to treat osteoarthritis in the knee. However, there is no conclusive evidence to show that it reduces pain or disability.[174] A Cochrane review of low-level laser therapy found unclear evidence of benefit,[175][better source needed] whereas another review found short-term pain relief for osteoarthritic knees.[176]

Further research is needed to determine if balnotherapy for osteoarthritis (mineral baths or spa treatments) improves a person's quality of life or ability to function.[177] The use of ice or cold packs may be beneficial; however, further research is needed.[178] There is no evidence of benefit from placing hot packs on joints.[178]

There is low quality evidence that therapeutic ultrasound may be beneficial for people with osteoarthritis of the knee; however, further research is needed to confirm and determine the degree and significance of this potential benefit.[179]

Therapeutic ultrasound is safe and helps reducing pain and improving physical function for knee osteoarthritis. While phonophoresis does not improve functions, it may offer greater pain relief than standard non-drug ultrasound.[180]

Continuous and pulsed ultrasound modes (especially 1 MHz, 2.5 W/cm2, 15min/ session, 3 session/ week, during 8 weeks protocol) may be effective in improving patients physical function and pain.[181]

There is weak evidence suggesting that electromagnetic field treatment may result in moderate pain relief; however, further research is necessary and it is not known if electromagnetic field treatment can improve quality of life or function.[182]

Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee may have positive effects on pain and function at 5 to 13 weeks post-injection.[183]

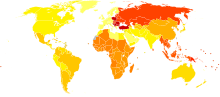

Epidemiology

[edit]

| no data ≤ 200 200–220 220–240 240–260 260–280 280–300 | 300–320 320–340 340–360 360–380 380–400 ≥ 400 |

Globally, as of 2010[update], approximately 250 million people had osteoarthritis of the knee (3.6% of the population).[185][186] Hip osteoarthritis affects about 0.85% of the population.[185]

As of 2004[update], osteoarthritis globally causes moderate to severe disability in 43.4 million people.[187] Together, knee and hip osteoarthritis had a ranking for disability globally of 11th among 291 disease conditions assessed.[185]

Middle East and North Africa (MENA)

[edit]In the Middle East and North Africa from 1990 to 2019, the prevalence of people with hip osteoarthritis increased three–fold over the three decades, a total of 1.28 million cases.[188] It increased 2.88-fold, from 6.16 million cases to 17.75 million, between 1990 and 2019 for knee osteoarthritis.[189] Hand osteoarthritis in MENA also increased 2.7-fold, from 1.6 million cases to 4.3 million from 1990 to 2019.[190]

United States

[edit]As of 2012[update], osteoarthritis affected 52.5 million people in the United States, approximately 50% of whom were 65 years or older.[191] It is estimated that 80% of the population have radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis by age 65, although only 60% of those will have symptoms.[192] The rate of osteoarthritis in the United States is forecast to be 78 million (26%) adults by 2040.[191]

In the United States, there were approximately 964,000 hospitalizations for osteoarthritis in 2011, a rate of 31 stays per 10,000 population.[193] With an aggregate cost of $14.8 billion ($15,400 per stay), it was the second-most expensive condition seen in US hospital stays in 2011. By payer, it was the second-most costly condition billed to Medicare and private insurance.[194][195]

Europe

[edit]In Europe, the number of individuals affected by osteoarthritis has increased from 27.9 million in 1990 to 50.8 million in 2019. Hand osteoarthritis was the second most prevalent type, affecting an estimated 12.5 million people. In 2019, Knee osteoarthritis was the 18th most common cause of years lived with disability (YLDs) in Europe, accounting for 1.28% of all YLDs. This has increased from 1.12% in 1990.[196]

India

[edit]In India, the number of individuals affected by osteoarthritis has increased from 23.46 million in 1990 to 62.35 million in 2019. Knee osteoarthritis was the most prevalent type of osteoarthritis, followed by hand osteoarthritis. In 2019, osteoarthritis was the 20th most common cause of years lived with disability (YLDs) in India, accounting for 1.48% of all YLDs, which increased from 1.25% and 23rd most common cause in 1990.[197]

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]Osteoarthritis is derived from the prefix osteo- (from Ancient Greek: ὀστέον, romanized: ostéon, lit. 'bone') combined with arthritis (from ἀρθρῖτῐς, arthrîtis, lit. ''of or in the joint''), which is itself derived from arthr- (from ἄρθρον, árthron, lit. ''joint, limb'') and -itis (from -ῖτις, -îtis, lit. ''pertaining to''), the latter suffix having come to be associated with inflammation.[198] The -itis of osteoarthritis could be considered misleading as inflammation is not a conspicuous feature. Some clinicians refer to this condition as osteoarthrosis to signify the lack of inflammatory response,[199] the suffix -osis (from -ωσις, -ōsis, lit. ''(abnormal) state, condition, or action'') simply referring to the pathosis itself.

Other animals

[edit]Osteoarthritis has been reported in several species of animals all over the world, including marine animals and even some fossils; including but not limited to: cats, many rodents, cattle, deer, rabbits, sheep, camels, elephants, buffalo, hyena, lions, mules, pigs, tigers, kangaroos, dolphins, dugong, and horses.[200]

Osteoarthritis has been reported in fossils of the large carnivorous dinosaur Allosaurus fragilis.[201]

Research

[edit]Therapies

[edit]Pharmaceutical agents that will alter the natural history of disease progression by arresting joint structural change and ameliorating symptoms are termed as disease modifying therapy.[63] Therapies under investigation include the following:

- Strontium ranelate – may decrease degeneration in osteoarthritis and improve outcomes[202][203]

- Gene therapy – Gene transfer strategies aim to target the disease process rather than the symptoms.[204] Cell-mediated gene therapy is also being studied.[205][206] One version was approved in South Korea for the treatment of moderate knee osteoarthritis, but later revoked for the mislabeling and the false reporting of an ingredient used.[207][208] The drug was administered intra-articularly.[208]

Cause

[edit]As well as attempting to find disease-modifying agents for osteoarthritis, there is emerging evidence that a system-based approach is necessary to find the causes of osteoarthritis.[209] A study conducted by scientists at the University of Twente found that osmolarity induced intracellular molecular crowding might drive the disease pathology.[210]

Diagnostic biomarkers

[edit]Guidelines outlining requirements for inclusion of soluble biomarkers in osteoarthritis clinical trials were published in 2015,[211] but there are no validated biomarkers used clinically to detect osteoarthritis, as of 2021.[212][213]

A 2015 systematic review of biomarkers for osteoarthritis looking for molecules that could be used for risk assessments found 37 different biochemical markers of bone and cartilage turnover in 25 publications.[214] The strongest evidence was for urinary C-terminal telopeptide of type II collagen (uCTX-II) as a prognostic marker for knee osteoarthritis progression, and serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) levels as a prognostic marker for incidence of both knee and hip osteoarthritis. A review of biomarkers in hip osteoarthritis also found associations with uCTX-II.[215] Procollagen type II C-terminal propeptide (PIICP) levels reflect type II collagen synthesis in body and within joint fluid PIICP levels can be used as a prognostic marker for early osteoarthritis.[216]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Osteoarthritis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. April 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Glyn-Jones S, Palmer AJ, Agricola R, Price AJ, Vincent TL, Weinans H, et al. (July 2015). "Osteoarthritis". Lancet. 386 (9991): 376–387. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60802-3. PMID 25748615. S2CID 208792655.

- ^ a b c d McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. (March 2014). "OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 22 (3): 363–388. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003. PMID 24462672.

- ^ a b GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ Arden N, Blanco F, Cooper C, Guermazi A, Hayashi D, Hunter D, et al. (2015). Atlas of Osteoarthritis. Springer. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-910315-16-3. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ "A National Public Health Agenda for Osteoarthritis 2020" (PDF). U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 27 July 2020.

- ^ Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S (April 2019). "Osteoarthritis". Lancet. 393 (10182): 1745–1759. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30417-9. PMID 31034380.

- ^ a b c d e Vingård E, Englund M, Järvholm B, Svensson O, Stenström K, Brolund A, et al. (1 September 2016). Occupational Exposures and Osteoarthritis: A systematic review and assessment of medical, social and ethical aspects. SBU Assessments (Report). Graphic design by Anna Edling. Stockholm: Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU). p. 1. 253 (in Swedish). Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Berenbaum F (January 2013). "Osteoarthritis as an inflammatory disease (osteoarthritis is not osteoarthrosis!)". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 21 (1): 16–21. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2012.11.012. PMID 23194896.

- ^ a b Conaghan P (2014). "Osteoarthritis – Care and management in adults". Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ Di Puccio F, Mattei L (January 2015). "Biotribology of artificial hip joints". World Journal of Orthopedics. 6 (1): 77–94. doi:10.5312/wjo.v6.i1.77. PMC 4303792. PMID 25621213.

- ^ a b March L, Smith EU, Hoy DG, Cross MJ, Sanchez-Riera L, Blyth F, et al. (June 2014). "Burden of disability due to musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 28 (3): 353–366. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2014.08.002. PMID 25481420.

- ^ Sinusas K (January 2012). "Osteoarthritis: diagnosis and treatment". American Family Physician. 85 (1): 49–56. PMID 22230308.

- ^ de Figueiredo EC, Figueiredo GC, Dantas RT (December 2011). "Influence of meteorological elements on osteoarthritis pain: a review of the literature" [Influence of meteorological elements on osteoarthritis pain: a review of the literature]. Revista Brasileira de Reumatologia (in Portuguese). 51 (6): 622–628. doi:10.1590/S0482-50042011000600008. PMID 22124595.

- ^ "Swollen knee". Mayo Clinic. 2017. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017.

- ^ "Bunions: Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. 8 November 2016. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ a b Brandt KD, Dieppe P, Radin E (January 2009). "Etiopathogenesis of osteoarthritis". The Medical Clinics of North America. 93 (1): 1–24, xv. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2008.08.009. PMID 19059018. S2CID 28990260.

- ^ Veronese N, Stubbs B, Solmi M, Smith T, Reginster JY, Maggi S (March 2018). "Osteoarthritis Increases the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative". The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging. 22 (3): 371–376. doi:10.1007/s12603-017-0941-0. ISSN 1279-7707. PMID 29484350.

- ^ Bosomworth NJ (September 2009). "Exercise and knee osteoarthritis: benefit or hazard?". Canadian Family Physician. 55 (9): 871–878. PMC 2743580. PMID 19752252.

- ^ Timmins KA, Leech RD, Batt ME, Edwards KL (May 2017). "Running and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis" (PDF). The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 45 (6): 1447–1457. doi:10.1177/0363546516657531. PMID 27519678. S2CID 21924096. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ Deweber K, Olszewski M, Ortolano R (2011). "Knuckle cracking and hand osteoarthritis". Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 24 (2): 169–174. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2011.02.100156. PMID 21383216.

- ^ Coggon D, Reading I, Croft P, McLaren M, Barrett D, Cooper C (May 2001). "Knee osteoarthritis and obesity". International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 25 (5): 622–627. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801585. PMID 11360143.

- ^ Tanamas SK, Wijethilake P, Wluka AE, Davies-Tuck ML, Urquhart DM, Wang Y, et al. (June 2011). "Sex hormones and structural changes in osteoarthritis: a systematic review". Maturitas. 69 (2): 141–156. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.03.019. PMID 21481553.

- ^ Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Dieppe PA, Hirsch R, Helmick CG, Jordan JM, et al. (October 2000). "Osteoarthritis: new insights. Part 1: the disease and its risk factors". Annals of Internal Medicine. 133 (8): 635–646. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-133-8-200010170-00016. PMID 11033593.

- ^ Ranganath LR, Jarvis JC, Gallagher JA (May 2013). "Recent advances in management of alkaptonuria (invited review; best practice article)". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 66 (5): 367–373. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2012-200877. PMID 23486607. S2CID 24860734.

- ^ "Birth Defects: Condition Information". www.nichd.nih.gov. September 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Congenital Disorders of Sexual Development". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ King KB, Rosenthal AK (June 2015). "The adverse effects of diabetes on osteoarthritis: update on clinical evidence and molecular mechanisms". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 23 (6): 841–850. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2015.03.031. PMC 5530368. PMID 25837996.

- ^ "Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "Hereditary Hemochromatosis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "Marfan Syndrome". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "Obesity". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "Arthritis, Infectious". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 2009. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Horowitz DL, Katzap E, Horowitz S, Barilla-LaBarca ML (September 2011). "Approach to septic arthritis". American Family Physician. 84 (6): 653–660. PMID 21916390.

- ^ El-Sobky T, Mahmoud S (July 2021). "Acute osteoarticular infections in children are frequently forgotten multidiscipline emergencies: beyond the technical skills". EFORT Open Reviews. 6 (7): 584–592. doi:10.1302/2058-5241.6.200155. PMC 8335954. PMID 34377550.

- ^ "Synovial Joints". OpenStax CNX. 25 April 2013. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ^ Sanchez-Adams J, Leddy HA, McNulty AL, O'Conor CJ, Guilak F (October 2014). "The mechanobiology of articular cartilage: bearing the burden of osteoarthritis". Current Rheumatology Reports. 16 (10): 451. doi:10.1007/s11926-014-0451-6. PMC 4682660. PMID 25182679.

- ^ a b c Maroudas AI (April 1976). "Balance between swelling pressure and collagen tension in normal and degenerate cartilage". Nature. 260 (5554): 808–809. Bibcode:1976Natur.260..808M. doi:10.1038/260808a0. PMID 1264261. S2CID 4214459.

- ^ Bollet AJ, Nance JL (July 1966). "Biochemical Findings in Normal and Osteoarthritic Articular Cartilage. II. Chondroitin Sulfate Concentration and Chain Length, Water, and Ash Content". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 45 (7): 1170–1177. doi:10.1172/JCI105423. PMC 292789. PMID 16695915.

- ^ a b Brocklehurst R, Bayliss MT, Maroudas A, Coysh HL, Freeman MA, Revell PA, et al. (January 1984). "The composition of normal and osteoarthritic articular cartilage from human knee joints. With special reference to unicompartmental replacement and osteotomy of the knee". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 66 (1): 95–106. doi:10.2106/00004623-198466010-00013. PMID 6690447.

- ^ Chou MC, Tsai PH, Huang GS, Lee HS, Lee CH, Lin MH, et al. (April 2009). "Correlation between the MR T2 value at 4.7 T and relative water content in articular cartilage in experimental osteoarthritis induced by ACL transection". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 17 (4): 441–447. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2008.09.009. PMID 18990590.

- ^ Grushko G, Schneiderman R, Maroudas A (1989). "Some biochemical and biophysical parameters for the study of the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: a comparison between the processes of ageing and degeneration in human hip cartilage". Connective Tissue Research. 19 (2–4): 149–176. doi:10.3109/03008208909043895. PMID 2805680.

- ^ Mankin HJ, Thrasher AZ (January 1975). "Water content and binding in normal and osteoarthritic human cartilage". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 57 (1): 76–80. doi:10.2106/00004623-197557010-00013. PMID 1123375.

- ^ a b Venn M, Maroudas A (April 1977). "Chemical composition and swelling of normal and osteoarthrotic femoral head cartilage. I. Chemical composition". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 36 (2): 121–129. doi:10.1136/ard.36.2.121. PMC 1006646. PMID 856064.

- ^ Madry H, Luyten FP, Facchini A (March 2012). "Biological aspects of early osteoarthritis". Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 20 (3): 407–422. doi:10.1007/s00167-011-1705-8. PMID 22009557. S2CID 31367901.

- ^ Englund M, Roemer FW, Hayashi D, Crema MD, Guermazi A (May 2012). "Meniscus pathology, osteoarthritis and the treatment controversy". Nature Reviews. Rheumatology. 8 (7): 412–419. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2012.69. PMID 22614907. S2CID 7725467.

- ^ Li G, Yin J, Gao J, Cheng TS, Pavlos NJ, Zhang C, et al. (2013). "Subchondral bone in osteoarthritis: insight into risk factors and microstructural changes". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 15 (6): 223. doi:10.1186/ar4405. PMC 4061721. PMID 24321104.

- ^ Hill CL, Gale DG, Chaisson CE, Skinner K, Kazis L, Gale ME, et al. (June 2001). "Knee effusions, popliteal cysts, and synovial thickening: association with knee pain in osteoarthritis". The Journal of Rheumatology. 28 (6): 1330–1337. PMID 11409127.

- ^ Felson DT, Chaisson CE, Hill CL, Totterman SM, Gale ME, Skinner KM, et al. (April 2001). "The association of bone marrow lesions with pain in knee osteoarthritis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 134 (7): 541–549. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-134-7-200104030-00007. PMID 11281736. S2CID 53091266.

- ^ Flynn JA, Choi MJ, Wooster DL (2013). Oxford American Handbook of Clinical Medicine. US: OUP. p. 400. ISBN 978-0-19-991494-4.

- ^ Seidman AJ, Limaiem F (2019). "Synovial Fluid Analysis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30725799. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ Zhang W, Doherty M, Peat G, Bierma-Zeinstra MA, Arden NK, Bresnihan B, et al. (March 2010). "EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 69 (3): 483–489. doi:10.1136/ard.2009.113100. PMID 19762361. S2CID 12319076.

- ^ Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Oster JD, Bernsen RM, Verhaar JA, Ginai AZ, Bohnen AM (August 2002). "Joint space narrowing and relationship with symptoms and signs in adults consulting for hip pain in primary care". The Journal of Rheumatology. 29 (8): 1713–1718. PMID 12180735.

- ^ Osteoarthritis (OA): Joint Disorders at The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

- ^ Phillips CR, Brasington RD (2010). "Osteoarthritis treatment update: Are NSAIDs still in the picture?". Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 12 February 2010. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ^ Kalunian KC (2013). "Patient information: Osteoarthritis symptoms and diagnosis (Beyond the Basics)". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ Altman R, Alarcón G, Appelrouth D, Bloch D, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. (November 1990). "The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hand". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 33 (11): 1601–1610. doi:10.1002/art.1780331101. PMID 2242058.

- ^ Quintana JM, Escobar A, Arostegui I, Bilbao A, Azkarate J, Goenaga JI, et al. (January 2006). "Health-related quality of life and appropriateness of knee or hip joint replacement". Archives of Internal Medicine. 166 (2): 220–226. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.2.220. PMID 16432092.

- ^ "Tönnis Classification of Osteoarthritis by Radiographic Changes". Society of Preventive Hip Surgery. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Punzi L, Ramonda R, Sfriso P (October 2004). "Erosive osteoarthritis". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 18 (5): 739–758. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2004.05.010. hdl:11577/2449059. PMID 15454130.

- ^ a b c d Flood J (March 2010). "The role of acetaminophen in the treatment of osteoarthritis". The American Journal of Managed Care. 16 (Suppl Management): S48 – S54. PMID 20297877. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015.

- ^ a b Leopoldino AO, Machado GC, Ferreira PH, Pinheiro MB, Day R, McLachlan AJ, et al. (February 2019). "Paracetamol versus placebo for knee and hip osteoarthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2): CD013273. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd013273. PMC 6388567. PMID 30801133.

- ^ a b Oo WM, Yu SP, Daniel MS, Hunter DJ (December 2018). "Disease-modifying drugs in osteoarthritis: current understanding and future therapeutics". Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs. 23 (4): 331–347. doi:10.1080/14728214.2018.1547706. PMID 30415584. S2CID 53284022.

- ^ a b Cibulka MT, White DM, Woehrle J, Harris-Hayes M, Enseki K, Fagerson TL, et al. (April 2009). "Hip pain and mobility deficits--hip osteoarthritis: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association". The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 39 (4): A1-25. doi:10.2519/jospt.2009.0301. PMC 3963282. PMID 19352008.

- ^ Georgiev T, Angelov AK (July 2019). "Modifiable risk factors in knee osteoarthritis: treatment implications". Rheumatology International. 39 (7): 1145–1157. doi:10.1007/s00296-019-04290-z. PMID 30911813. S2CID 85493753.

- ^ "How to improve discussions about osteoarthritis in primary care". NIHR Evidence. 23 June 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_51244. S2CID 251782088.

- ^ Vennik J, Hughes S, Smith KA, Misurya P, Bostock J, Howick J, et al. (July 2022). "Patient and practitioner priorities and concerns about primary healthcare interactions for osteoarthritis: A meta-ethnography". Patient Education and Counseling. 105 (7): 1865–1877. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2022.01.009. PMID 35125208. S2CID 246314113.

- ^ a b Hunter DJ, Eckstein F (2009). "Exercise and osteoarthritis". Journal of Anatomy. 214 (2): 197–207. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.01013.x. PMC 2667877. PMID 19207981.

- ^ Charlesworth J, Fitzpatrick J, Orchard J (2019). "Osteoarthritis- a systematic review of long-term safety implications for osteoarthritis of the knee". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 20 (1): 151. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2525-0. PMC 6454763. PMID 30961569.

- ^ Ho J, Mak CC, Sharma V, To K, Khan W (October 2022). "Mendelian Randomization Studies of Lifestyle-Related Risk Factors for Osteoarthritis: A PRISMA Review and Meta-Analysis". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (19): 11906. doi:10.3390/ijms231911906. PMC 9570129. PMID 36233208.

- ^ Hagen KB, Dagfinrud H, Moe RH, Østerås N, Kjeken I, Grotle M, et al. (December 2012). "Exercise therapy for bone and muscle health: an overview of systematic reviews". BMC Medicine. 10: 167. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-10-167. PMC 3568719. PMID 23253613.

- ^ Fransen M, McConnell S, Hernandez-Molina G, Reichenbach S (April 2014). "Exercise for osteoarthritis of the hip". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (4): CD007912. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007912.pub2. PMC 10898220. PMID 24756895.

- ^ a b Hurley M, Dickson K, Hallett R, Grant R, Hauari H, Walsh N, et al. (April 2018). "Exercise interventions and patient beliefs for people with hip, knee or hip and knee osteoarthritis: a mixed methods review". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (4): CD010842. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010842.pub2. PMC 6494515. PMID 29664187.

- ^ a b Juhl C, Christensen R, Roos EM, Zhang W, Lund H (March 2014). "Impact of exercise type and dose on pain and disability in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials". Arthritis & Rheumatology. 66 (3): 622–636. doi:10.1002/art.38290. PMID 24574223. S2CID 24620456.

- ^ Wang SY, Olson-Kellogg B, Shamliyan TA, Choi JY, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL (November 2012). "Physical therapy interventions for knee pain secondary to osteoarthritis: a systematic review". Annals of Internal Medicine. 157 (9): 632–644. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00007. PMID 23128863. S2CID 17423569.

- ^ Jordan JL, Holden MA, Mason EE, Foster NE (January 2010). "Interventions to improve adherence to exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (1): CD005956. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005956.pub2. PMC 6769154. PMID 20091582.

- ^ a b Nahin RL, Boineau R, Khalsa PS, Stussman BJ, Weber WJ (September 2016). "Evidence-Based Evaluation of Complementary Health Approaches for Pain Management in the United States". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 91 (9): 1292–1306. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.007. PMC 5032142. PMID 27594189.

- ^ French HP, Brennan A, White B, Cusack T (April 2011). "Manual therapy for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee - a systematic review". Manual Therapy. 16 (2): 109–117. doi:10.1016/j.math.2010.10.011. PMID 21146444.

- ^ Lu M, Su Y, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Wang W, He Z, et al. (August 2015). "Effectiveness of aquatic exercise for treatment of knee osteoarthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis". Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie. 74 (6): 543–552. doi:10.1007/s00393-014-1559-9. PMID 25691109. S2CID 19135129.

- ^ Sturnieks DL, Tiedemann A, Chapman K, Munro B, Murray SM, Lord SR (November 2004). "Physiological risk factors for falls in older people with lower limb arthritis". The Journal of Rheumatology. 31 (11): 2272–2279. PMID 15517643.

- ^ Barbour KE, Stevens JA, Helmick CG, Luo YH, Murphy LB, Hootman JM, et al. (May 2014). "Falls and fall injuries among adults with arthritis--United States, 2012". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 63 (17): 379–383. PMC 4584889. PMID 24785984.

- ^ Østerås N, Kjeken I, Smedslund G, Moe RH, Slatkowsky-Christensen B, Uhlig T, et al. (January 2017). "Exercise for hand osteoarthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD010388. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010388.pub2. PMC 6464796. PMID 28141914.

- ^ Øiestad BE, Juhl CB, Culvenor AG, Berg B, Thorlund JB (March 2022). "Knee extensor muscle weakness is a risk factor for the development of knee osteoarthritis: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including 46 819 men and women". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 56 (6): 349–355. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2021-104861. PMID 34916210.

- ^ Penny P, Geere J, Smith TO (October 2013). "A systematic review investigating the efficacy of laterally wedged insoles for medial knee osteoarthritis". Rheumatology International. 33 (10): 2529–2538. doi:10.1007/s00296-013-2760-x. PMID 23612781. S2CID 20664287.

- ^ Parkes MJ, Maricar N, Lunt M, LaValley MP, Jones RK, Segal NA, et al. (August 2013). "Lateral wedge insoles as a conservative treatment for pain in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis". JAMA. 310 (7): 722–730. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.243229. PMC 4458141. PMID 23989797.

- ^ a b Duivenvoorden T, Brouwer RW, van Raaij TM, Verhagen AP, Verhaar JA, Bierma-Zeinstra SM (March 2015). "Braces and orthoses for treating osteoarthritis of the knee". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (3): CD004020. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004020.pub3. PMC 7173742. PMID 25773267. S2CID 35262399.

- ^ Page CJ, Hinman RS, Bennell KL (May 2011). "Physiotherapy management of knee osteoarthritis". International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 14 (2): 145–151. doi:10.1111/j.1756-185X.2011.01612.x. PMID 21518313. S2CID 41951368.

- ^ "Osteoarthritis Lifestyle and home remedies". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016.

- ^ Bartels EM, Juhl CB, Christensen R, Hagen KB, Danneskiold-Samsøe B, Dagfinrud H, et al. (March 2016). "Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (3): CD005523. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005523.pub3. hdl:11250/2481966. PMC 9942938. PMID 27007113.

- ^ Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, Van der Esch M, Simic M, Bennell KL (January 2015). "Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD004376. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004376.pub3. PMC 10094004. PMID 25569281. S2CID 205173688.

- ^ White DK, Tudor-Locke C, Zhang Y, Fielding R, LaValley M, Felson DT, et al. (September 2014). "Daily walking and the risk of incident functional limitation in knee osteoarthritis: an observational study". Arthritis Care & Research. 66 (9): 1328–1336. doi:10.1002/acr.22362. PMC 4146701. PMID 24923633.

- ^ Bartels EM, Juhl CB, Christensen R, Hagen KB, Danneskiold-Samsøe B, Dagfinrud H, et al. (March 2016). "Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (3): CD005523. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005523.pub3. PMC 9942938. PMID 27007113.

- ^ a b c Brosseau L, Yonge KA, Tugwell P (2003). "Thermotherapy for treatment of osteoarthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003 (4): CD004522. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004522. PMC 6669258. PMID 14584019.

- ^ a b c d "Pain Relief with NSAID Medications". Consumer Reports. January 2016. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ a b Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden N, et al. (September 2007). "OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part I: critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 15 (9): 981–1000. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2007.06.014. PMID 17719803.

- ^ Machado GC, Maher CG, Ferreira PH, Pinheiro MB, Lin CW, Day RO, et al. (March 2015). "Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials". BMJ. 350: h1225. doi:10.1136/bmj.h1225. PMC 4381278. PMID 25828856.

- ^ Chen YF, Jobanputra P, Barton P, Bryan S, Fry-Smith A, Harris G, et al. (April 2008). "Cyclooxygenase-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (etodolac, meloxicam, celecoxib, rofecoxib, etoricoxib, valdecoxib and lumiracoxib) for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and economic evaluation". Health Technology Assessment. 12 (11): 1–278, iii. doi:10.3310/hta12110. PMID 18405470.

- ^ Wielage RC, Myers JA, Klein RW, Happich M (December 2013). "Cost-effectiveness analyses of osteoarthritis oral therapies: a systematic review". Applied Health Economics and Health Policy. 11 (6): 593–618. doi:10.1007/s40258-013-0061-x. PMID 24214160. S2CID 207482912.

- ^ van Walsem A, Pandhi S, Nixon RM, Guyot P, Karabis A, Moore RA (March 2015). "Relative benefit-risk comparing diclofenac to other traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis: a network meta-analysis". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 17 (1): 66. doi:10.1186/s13075-015-0554-0. PMC 4411793. PMID 25879879.

- ^ Puljak L, Marin A, Vrdoljak D, Markotic F, Utrobicic A, Tugwell P (May 2017). "Celecoxib for osteoarthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5): CD009865. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009865.pub2. PMC 6481745. PMID 28530031.

- ^ a b Derry S, Conaghan P, Da Silva JA, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA (April 2016). "Topical NSAIDs for chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (4): CD007400. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007400.pub3. PMC 6494263. PMID 27103611.

- ^ Garner SE, Fidan DD, Frankish R, Maxwell L (January 2005). "Rofecoxib for osteoarthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005 (1): CD005115. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005115. PMC 8864971. PMID 15654705.

- ^ Karabis A, Nikolakopoulos S, Pandhi S, Papadimitropoulou K, Nixon R, Chaves RL, et al. (March 2016). "High correlation of VAS pain scores after 2 and 6 weeks of treatment with VAS pain scores at 12 weeks in randomised controlled trials in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: meta-analysis and implications". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 18: 73. doi:10.1186/s13075-016-0972-7. PMC 4818534. PMID 27036633.

- ^ Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, et al. (April 2012). "American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee". Arthritis Care & Research. 64 (4): 465–474. doi:10.1002/acr.21596. PMID 22563589. S2CID 11711160.

- ^ a b da Costa BR, Nüesch E, Kasteler R, Husni E, Welch V, Rutjes AW, et al. (September 2014). "Oral or transdermal opioids for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (9): CD003115. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003115.pub4. PMC 10993204. PMID 25229835. S2CID 205168274.

- ^ a b Toupin April K, Bisaillon J, Welch V, Maxwell LJ, Jüni P, Rutjes AW, et al. (Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group) (May 2019). "Tramadol for osteoarthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5): CD005522. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005522.pub3. PMC 6536297. PMID 31132298.

- ^ a b da Costa BR, Nüesch E, Reichenbach S, Jüni P, Rutjes AW (November 2012). "Doxycycline for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 (11): CD007323. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007323.pub3. PMC 11491192. PMID 23152242.

- ^ García-Coronado JM, Martínez-Olvera L, Elizondo-Omaña RE, Acosta-Olivo CA, Vilchez-Cavazos F, Simental-Mendía LE, et al. (March 2019). "Effect of collagen supplementation on osteoarthritis symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials". International Orthopaedics. 43 (3): 531–538. doi:10.1007/s00264-018-4211-5. PMID 30368550. S2CID 53080408.

- ^ a b c d e f g De Silva V, El-Metwally A, Ernst E, Lewith G, Macfarlane GJ (May 2011). "Evidence for the efficacy of complementary and alternative medicines in the management of osteoarthritis: a systematic review". Rheumatology. 50 (5): 911–920. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keq379. PMID 21169345.

- ^ Cameron M, Gagnier JJ, Little CV, Parsons TJ, Blümle A, Chrubasik S (November 2009). "Evidence of effectiveness of herbal medicinal products in the treatment of arthritis. Part I: Osteoarthritis". Phytotherapy Research. 23 (11): 1497–1515. doi:10.1002/ptr.3007. hdl:2027.42/64567. PMID 19856319. S2CID 43530618.

- ^ Altman R, Barkin RL (March 2009). "Topical therapy for osteoarthritis: clinical and pharmacologic perspectives". Postgraduate Medicine. 121 (2): 139–147. doi:10.3810/pgm.2009.03.1986. PMID 19332972. S2CID 20975564.

- ^ Yeap PM, Robinson P (December 2017). "Ultrasound Diagnostic and Therapeutic Injections of the Hip and Groin". Journal of the Belgian Society of Radiology. 101 (Suppl 2): 6. doi:10.5334/jbr-btr.1371. PMC 6251072. PMID 30498802.

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0) - ^ Charlesworth J, Fitzpatrick J, Perera NK, Orchard J (April 2019). "Osteoarthritis- a systematic review of long-term safety implications for osteoarthritis of the knee". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 20 (1): 151. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2525-0. PMC 6454763. PMID 30961569.

- ^ Oo WM, Liu X, Hunter DJ (December 2019). "Pharmacodynamics, efficacy, safety and administration of intra-articular therapies for knee osteoarthritis". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 15 (12): 1021–1032. doi:10.1080/17425255.2019.1691997. PMID 31709838. S2CID 207946424.

- ^ Kleinschmidt AC, Singh A, Hussain S, Lovell GA, Shee AW (December 2022). "How Effective Are Non-Operative Intra-Articular Treatments for Bone Marrow Lesions in Knee Osteoarthritis in Adults? A Systematic Review of Controlled Clinical Trials". Pharmaceuticals. 15 (12): 1555. doi:10.3390/ph15121555. PMC 9787030. PMID 36559005.

- ^ Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F (April 2004). "Corticosteroid injections for osteoarthritis of the knee: meta-analysis". BMJ. 328 (7444): 869. doi:10.1136/bmj.38039.573970.7C. PMC 387479. PMID 15039276.

- ^ Jüni P, Hari R, Rutjes AW, Fischer R, Silletta MG, Reichenbach S, et al. (October 2015). "Intra-articular corticosteroid for knee osteoarthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (10): CD005328. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005328.pub3. PMC 8884338. PMID 26490760.

- ^ Wernecke C, Braun HJ, Dragoo JL (May 2015). "The Effect of Intra-articular Corticosteroids on Articular Cartilage: A Systematic Review". Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 3 (5): 2325967115581163. doi:10.1177/2325967115581163. PMC 4622344. PMID 26674652.

- ^ McAlindon TE, LaValley MP, Harvey WF, Price LL, Driban JB, Zhang M, et al. (May 2017). "Effect of Intra-articular Triamcinolone vs Saline on Knee Cartilage Volume and Pain in Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical Trial". JAMA. 317 (19): 1967–1975. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.5283. PMC 5815012. PMID 28510679.

- ^ Taliaferro K, Crawford A, Jabara J, Lynch J, Jung E, Zvirbulis R, et al. (July 2018). "Intraocular Pressure Increases After Intraarticular Knee Injection With Triamcinolone but Not Hyaluronic Acid". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (Level-II therapeutic study). 476 (7): 1420–1425. doi:10.1007/s11999.0000000000000261. LCCN 53007647. OCLC 01554937. PMC 6437574. PMID 29533245.

- ^ a b Rutjes AW, Jüni P, da Costa BR, Trelle S, Nüesch E, Reichenbach S (August 2012). "Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 157 (3): 180–191. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-3-201208070-00473. PMID 22868835. S2CID 5660398.

- ^ Jevsevar D, Donnelly P, Brown GA, Cummins DS (December 2015). "Viscosupplementation for Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Systematic Review of the Evidence". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 97 (24): 2047–2060. doi:10.2106/jbjs.n.00743. PMID 26677239.

- ^ Witteveen AG, Hofstad CJ, Kerkhoffs GM (October 2015). "Hyaluronic acid and other conservative treatment options for osteoarthritis of the ankle". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (10): CD010643. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010643.pub2. PMC 9254328. PMID 26475434.

It is unclear if there is a benefit or harm for HA as treatment for ankle OA

- ^ Khoshbin A, Leroux T, Wasserstein D, Marks P, Theodoropoulos J, Ogilvie-Harris D, et al. (December 2013). "The efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review with quantitative synthesis". Arthroscopy. 29 (12): 2037–2048. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2013.09.006. PMID 24286802.

- ^ Rodriguez-Merchan EC (September 2013). "Intraarticular Injections of Platelet-rich Plasma (PRP) in the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis". The Archives of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1 (1): 5–8. PMC 4151401. PMID 25207275.

- ^ Moraes VY, Lenza M, Tamaoki MJ, Faloppa F, Belloti JC (April 2014). "Platelet-rich therapies for musculoskeletal soft tissue injuries". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (4): CD010071. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010071.pub3. PMC 6464921. PMID 24782334.

- ^ Kampen WU, Boddenberg-Pätzold B, Fischer M, Gabriel M, Klett R, Konijnenberg M, et al. (January 2022). "The EANM guideline for radiosynoviorthesis". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 49 (2): 681–708. doi:10.1007/s00259-021-05541-7. PMC 8803784. PMID 34671820.

- ^ Dove AP, Cmelak A, Darrow K, McComas KN, Chowdhary M, Beckta J, et al. (1 October 2022). "The Use of Low-Dose Radiation Therapy in Osteoarthritis: A Review". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 114 (2): 203–220. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2022.04.029. ISSN 1879-355X. PMID 35504501.

- ^ Manke E, Yeo Eng Meng N, Rammelt S (2020). "Ankle Arthrodesis - a Review of Current Techniques and Results". Acta Chirurgiae Orthopaedicae et Traumatologiae Cechoslovaca. 87 (4): 225–236. doi:10.55095/achot2020/035. PMID 32940217. S2CID 221770606.

- ^ Santaguida PL, Hawker GA, Hudak PL, Glazier R, Mahomed NN, Kreder HJ, et al. (December 2008). "Patient characteristics affecting the prognosis of total hip and knee joint arthroplasty: a systematic review". Canadian Journal of Surgery. Journal Canadien de Chirurgie. 51 (6): 428–436. PMC 2592576. PMID 19057730.

- ^ Carr AJ, Robertsson O, Graves S, Price AJ, Arden NK, Judge A, et al. (April 2012). "Knee replacement". Lancet. 379 (9823): 1331–1340. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60752-6. PMID 22398175. S2CID 28484710.

- ^ Jenkins PJ, Clement ND, Hamilton DF, Gaston P, Patton JT, Howie CR (January 2013). "Predicting the cost-effectiveness of total hip and knee replacement: a health economic analysis". The Bone & Joint Journal. 95-B (1): 115–121. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.95B1.29835. PMID 23307684.

- ^ Daigle ME, Weinstein AM, Katz JN, Losina E (October 2012). "The cost-effectiveness of total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review of published literature". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 26 (5): 649–658. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2012.07.013. PMC 3879923. PMID 23218429.

- ^ Ferket BS, Feldman Z, Zhou J, Oei EH, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Mazumdar M (March 2017). "Impact of total knee replacement practice: cost effectiveness analysis of data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative". BMJ. 356: j1131. doi:10.1136/bmj.j1131. PMC 6284324. PMID 28351833.

- ^ Shan L, Shan B, Suzuki A, Nouh F, Saxena A (January 2015). "Intermediate and long-term quality of life after total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 97 (2): 156–168. doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.00372. PMID 25609443.

- ^ Rat AC, Guillemin F, Osnowycz G, Delagoutte JP, Cuny C, Mainard D, et al. (January 2010). "Total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis: mid- and long-term quality of life". Arthritis Care & Research. 62 (1): 54–62. doi:10.1002/acr.20014. PMID 20191491. S2CID 27864530.

- ^ Singh JA, Sperling J, Buchbinder R, McMaken K (October 2010). "Surgery for shoulder osteoarthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD008089. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008089.pub2. PMID 20927773.

- ^ "Osteochondral Autograft & Allograft". Washington University Orthopedics. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Favinger JL, Ha AS, Brage ME, Chew FS (2015). "Osteoarticular transplantation: recognizing expected postsurgical appearances and complications". Radiographics. 35 (3): 780–792. doi:10.1148/rg.2015140070. PMID 25969934.

- ^ Hunziker EB, Lippuner K, Keel MJ, Shintani N (March 2015). "An educational review of cartilage repair: precepts & practice--myths & misconceptions--progress & prospects". Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 23 (3): 334–350. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2014.12.011. PMID 25534362.

- ^ Mistry H, Connock M, Pink J, Shyangdan D, Clar C, Royle P, et al. (February 2017). "Autologous chondrocyte implantation in the knee: systematic review and economic evaluation". Health Technology Assessment. 21 (6): 1–294. doi:10.3310/hta21060. PMC 5346885. PMID 28244303.

- ^ a b c Al Mana L, Rajaratnam K (November 2020). "Cochrane in CORR®: Shoulder Replacement Surgery For Osteoarthritis And Rotator Cuff Tear Arthropathy". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 478 (11): 2431–2433. doi:10.1097/CORR.0000000000001523. PMC 7571914. PMID 33055541.

- ^ a b c Craig RS, Goodier H, Singh JA, Hopewell S, Rees JL (April 2020). "Shoulder replacement surgery for osteoarthritis and rotator cuff tear arthropathy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (4): CD012879. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012879.pub2. PMC 7173708. PMID 32315453.

- ^ Brouwer RW, Huizinga MR, Duivenvoorden T, van Raaij TM, Verhagen AP, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. (December 2014). "Osteotomy for treating knee osteoarthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (12): CD004019. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004019.pub4. PMC 7173694. PMID 25503775.

- ^ a b Palmer JS, Monk AP, Hopewell S, Bayliss LE, Jackson W, Beard DJ, et al. (July 2019). "Surgical interventions for symptomatic mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (7): CD012128. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012128.pub2. PMC 6639936. PMID 31322289.

- ^ Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, Goode AP, Jordan JM (June 2014). "A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: The chronic osteoarthritis management initiative of the U.S. bone and joint initiative". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 43 (6): 701–712. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.11.012. PMID 24387819.

- ^ Katz JN, Brownlee SA, Jones MH (February 2014). "The role of arthroscopy in the management of knee osteoarthritis". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 28 (1): 143–156. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2014.01.008. PMC 4010873. PMID 24792949.

- ^ Thorlund JB, Juhl CB, Roos EM, Lohmander LS (June 2015). "Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee: systematic review and meta-analysis of benefits and harms". BMJ. 350: h2747. doi:10.1136/bmj.h2747. PMC 4469973. PMID 26080045.

- ^ Burdett N, McNeil JD (September 2012). "Difficulties with assessing the benefit of glucosamine sulphate as a treatment for osteoarthritis". International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare. 10 (3): 222–226. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1609.2012.00279.x. PMID 22925619.

- ^ Wandel S, Jüni P, Tendal B, Nüesch E, Villiger PM, Welton NJ, et al. (September 2010). "Effects of glucosamine, chondroitin, or placebo in patients with osteoarthritis of hip or knee: network meta-analysis". BMJ. 341: c4675. doi:10.1136/bmj.c4675. PMC 2941572. PMID 20847017.

- ^ Wu D, Huang Y, Gu Y, Fan W (June 2013). "Efficacies of different preparations of glucosamine for the treatment of osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 67 (6): 585–594. doi:10.1111/ijcp.12115. PMID 23679910. S2CID 24251411.

- ^ Analgesics for Osteoarthritis: An Update of the 2006 Comparative Effectiveness Review (Report). Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Vol. 38. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). October 2011. PMID 22091473. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013.

- ^ Miller KL, Clegg DO (February 2011). "Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate". Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America. 37 (1): 103–118. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2010.11.007. PMID 21220090.

The best current evidence suggests that the effect of these supplements, alone or in combination, on OA pain, function, and radiographic change is marginal at best.