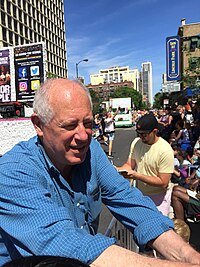

Pat Quinn | |

|---|---|

| |

| 41st Governor of Illinois | |

| In office January 29, 2009 – January 12, 2015 | |

| Lieutenant | Vacant (2009–2011) Sheila Simon (2011–2015) |

| Preceded by | Rod Blagojevich |

| Succeeded by | Bruce Rauner |

| 45th Lieutenant Governor of Illinois | |

| In office January 13, 2003 – January 29, 2009 | |

| Governor | Rod Blagojevich |

| Preceded by | Corinne Wood |

| Succeeded by | Sheila Simon |

| 70th Treasurer of Illinois | |

| In office January 14, 1991 – January 9, 1995 | |

| Governor | Jim Edgar |

| Preceded by | Jerome Cosentino |

| Succeeded by | Judy Baar Topinka |

| Commissioner of the Cook County Board of Appeals | |

| In office 1982–1986 | |

| Preceded by | Seymour Zaban |

| Succeeded by | Wilson Frost |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Patrick Joseph Quinn Jr. December 16, 1948 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Julie Hancock

(m. 1982; div. 1986) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Georgetown University (BS) Northwestern University (JD) |

| Signature | |

Patrick Joseph Quinn (born December 16, 1948) is an American politician who served as the 41st governor of Illinois from 2009 to 2015. A Democrat, Quinn began his career as an activist by founding the Coalition for Political Honesty, which used citizen-initiated referendum questions to advocate for political reforms,[1] and later served as a commissioner on the Cook County Board of (Property) Tax Appeals from 1982 to 1986, Illinois State Treasurer from 1991 to 1995, and Lieutenant Governor of Illinois from 2003 to 2009.

Born in Chicago, Illinois, Quinn is a graduate of Georgetown University and Northwestern University School of Law. Quinn began his political career working as an aide to then-Illinois Governor Dan Walker before launching a series of citizen-led petition drives, most notably the 1980 Cutback Amendment, which reduced the size of the Illinois House of Representatives from 177 to 118. It marked the first and only time in state history that Illinois voters had used initiative petition and binding referendum to enact a constitutional amendment or law.

After the passage of the Cutback Amendment, Quinn continued to organize petition drives and was elected as a commissioner on the Cook County Board of (Property) Tax Appeals in 1982; he later served as revenue director in the administration of Chicago Mayor Harold Washington. He was elected Treasurer of Illinois in 1990 and ran for secretary of state in 1994, United States senator in 1996, lieutenant governor in 1998, and attorney general in 2018.[2]

In Illinois' 2002 gubernatorial election, Quinn won the Democratic nomination for Lieutenant Governor of Illinois in the primary and was paired with then-U.S. Representative Rod Blagojevich in the general election. He was sworn into office as lieutenant governor in 2003, becoming the first Democrat to hold the office since 1977. Both Quinn and Blagojevich were reelected in 2006. Quinn assumed the governorship on January 29, 2009, after Governor Blagojevich was impeached and removed from office on corruption charges, with the contrast between the two men prompting the New York Times to call Quinn "the anti-Blagojevich."[3]

Quinn secured a full term in office in the 2010 gubernatorial election, defeating Republican State Senator Bill Brady by a margin of less than 1% out of about 3.5 million votes cast. The election was ranked by Politico as one of the top upsets that year.[4] While in office, Quinn worked to provide voters the power to recall a sitting governor, passed a $31 billion capital construction plan,[5] legalized civil unions and same-sex marriage (prior to the 2015 Obergefell v. Hodges decision by the United States Supreme Court),[6] expanded access to healthcare with the Affordable Care Act, and abolished the death penalty.[7]

Quinn was narrowly defeated in 2014 by Republican candidate Bruce Rauner.[8]

Early life and education

[edit]Quinn was born December 16, 1948, in the South Shore neighborhood of Chicago, the son of Patrick Joseph "P. J." Quinn and the former Eileen Prindiville.

Quinn's father, P. J., enlisted in the U.S. Navy at the outbreak of World War II, serving in the Pacific Theater aboard several ships including the USS Bon Homme Richard. He served for three years, one month, and 15 days. In a commendation letter from his commanding officer, Quinn is described as “one of the finest men with whom I have ever worked. Extremely capable in his work, he was at all times cheerful, earnest, cooperative, frank, and honest.”[9] P. J. later worked for the Archdiocese of Chicago.[10][11][12][13]

Eileen Prindiville was born before American women had the right to vote under the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1920 and graduated from the Academy of Our Lady in 1935. Eileen worked for decades as an assistant to the principal of the Hinsdale Public Middle School.

P. J. and Eileen Quinn raised three sons in a single-family home in Hinsdale, Illinois, thanks to a mortgage secured by the Veterans Administration.

Quinn attended St. Isaac Jogues in Hinsdale for elementary school before attending Fenwick High School in Oak Park. Quinn was the cross-country team captain and sports editor of the school newspaper. Quinn then on to graduate from Georgetown University in 1971 with a Bachelor of Science in Foreign Service (BSFS) degree from the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, where he was a student of Professor Jan Karski and a sports editor for The Hoya.

After serving in state government and spearheading two major petition drives, Quinn earned a Juris Doctor degree from Northwestern University School of Law in 1980, during the fight for the Cutback Amendment.

Quinn is the eldest of three boys. Tom Quinn has been an attorney since 1979 and his proudest moment in the courtroom was winning a legal settlement in a major case that targeted housing discrimination in the south suburbs of Chicago. John Quinn was an American history teacher at Fenwick since 1980 and is an Illinois Hall of Fame basketball coach. He has also received the Golden Apple Award for Excellence in Teaching. P. J., Eileen, Tom, and John always played energetic roles in their son’s petition and referendum drives and political campaigns.

Family history and heritage

[edit]Quinn's relatives railed from County Mayo in Ireland, where the term boycott was termed following action against unpopular land agent Charles Boycott. Quinn’s grandparents left Ireland in the late 1800s and early 1900s to move to the United States. His paternal grandfather, also named Patrick Quinn, had a stint as a copper miner in Butte, Montana, then came to Chicago’s South Side. In 1915, he opened “Quinn’s Groceries, Meats & Vegetables” in Chicago. His motto was “Quinn for Quality, Quantity and Service.”[14] Quinn’s father, P. J. Quinn, worked in the family store and graduated from De La Salle High School in 1932.

Early activism

[edit]Before running for public office, Quinn worked as an organizer for Dan Walker in the 1972 Illinois gubernatorial election, working statewide on college campuses (1972 being the first election in which 18-year-olds could vote) before organizing the Metro East and southwestern Illinois in the general. From January 1973 to July 1975, Quinn served as an ombudsman and assistant to the governor for labor and worker safety.[15]

From July 1975 to December 1982, Quinn served as the executive director of the Coalition for Political Honesty, a volunteer initiative, petition, and referendum organization. From October 1975 to 1976, the Coalition collected signatures and advocated for the Political Honesty Initiative, which called for referendums on three reforms: ending double dipping, conflict-of-interest voting by Illinois legislators, and the practice of advance pay, wherein legislators could collect their entire annual salary on their first day in office. Radio host Wally Phillips of WGN-AM was among the Political Honesty Initiative petition signers and one of its greatest supporters. Petitions containing 635,128 signatures (an all-time record) were filed with the Illinois Secretary of State at the State Capitol on April 30, 1976, leading the General Assembly to quickly pass a bill in May 1976, ending the 100-year-old advance pay practice once and for all by requiring legislators to be paid monthly after doing their work.[1] The question did not appear on the 1976 ballot following the case of Coalition for Political Honesty v. State Board of Elections, which hinged on whether the word "and" in the 1970 Illinois constitution was "conjunctive" or "disjunctive."[16]

In 1977, Quinn led a statewide petition drive for open primaries in Illinois, and in 1978, a statewide petition drive for a property tax freeze. On December 16, 1978, the anniversary of the Boston Tea Party, Quinn led a campaign to send 40,000 tea bags to the office of Governor James R. Thompson to protest a 40% pay raise for legislators and the governor.[17]

Beginning in 1979, Quinn and the Coalition for Political Honesty began a petition drive for what became known as the Cutback Amendment, a provision to reduce the size of the Illinois House of Representatives from 177 to 118 and abolish cumulative voting, requiring House members to run in single-member districts. The proposal was supported by the League of Women Voters. The Illinois General Assembly quickly passed legislation to make it more difficult to pass initiative petitions. After submitting 477,112 signatures, a court struck the question from the ballot, citing the new law, resulting in a lawsuit, Coalition for Political Honesty v. State Board of Elections (II) (1980), the first Illinois Supreme Court case that found that strict scrutiny applied to initiative powers in the Illinois Constitution and which placed the question back on the 1980 ballot.[18]

Illinois voters approved the Cutback Amendment by a 68.7 percent margin (2,112,224 to 962,325) on November 4, 1980.[19][20][21] It marked the first and only time in state history that Illinois voters had used initiative petition and binding referendum to enact a constitutional amendment or law.

In 1981 and 1982, Quinn led a petition to amend the 1970 Illinois Constitution with the "Illinois Initiative". This amendment was intended to increase the power of petition and binding referendums in the political process.[22] The petition drive was successful, but the Illinois Appellate Court ruled in Lousin v. State Board of Elections (1982) that it could not appear on the ballot.[23]

In 1982, Quinn and the Coalition placed a question on the Chicago ballot calling for a Citizens Utility Board to protect consumers. In 1983, 110 towns in Illinois placed the question on their ballots. On September 20, 1983, Gov. James Thompson signed the Citizens Utility Board (CUB) law (Public Act 83-945) to provide “effective and democratic representation of utility consumers before the Illinois Commerce Commission, the General Assembly, the courts and other public bodies, and by providing consumer education on utility services prices and methods of energy conservation.”

In July 1984, the first CUB membership inserts were included in 3.5 million phone bills. Some 30,000 consumers quickly sent back $5 to join the new group. The next month, 2.3 million gas customers received the CUB insert along with 5 million electric customers in September 1984. Within six months, CUB had grown to 100,000 dues-paying members from all 102 counties in Illinois.[24]

Political career

[edit]Cook County Board of Appeals (1982–1986)

[edit]In 1982, Quinn won the Democratic primary to serve as a commissioner on the Cook County Board of Appeals, now known as the Cook County Board of Review.[22] In a three-way primary for two spots, Quinn was able to beat one of the incumbents who had presided over a scandal in which 37 people were convicted for fixing property tax appeal cases. Quinn was regarded as a positive reforming figure on the Board of Appeals, which had long been regarded to be plagued by corruption.

In his term in office, the board resisted awarding excessive tax rebates to politically-connected wealthy individuals, as the board had long done. During his first year, this largely resulted in tax rebates awarded by the board decreasing from $444 million in the preceding year to $75 million. This had an effect of increasing the county's tax revenue.[25] During his time on the board, Quinn was also instrumental in the creation of the "Citizens Utility Board", a consumer watchdog organization.[26]

Quinn did not seek re-election to the board, and was succeeded by Chicago alderman Wilson Frost.

1986 state treasurer campaign

[edit]In 1986, Quinn chose to run in the Democratic primary for Illinois treasurer in a four-way primary that also included incumbent treasurer James Donnewald, former treasurer Jerome Cosentino, and LaRouche movement member Robert D. Hart (who had the formal backing of Lyndon LaRouche's NDPC).[27]

In the March 18, 1986, Democratic primary, Donnelwald lost to his predecessor, Cosentino, 29.47% to 30.22%, with Quinn coming in a close third with 26.18%.[28][29]

Chicago Revenue Director (1987)

[edit]Quinn served in the administration of Chicago Mayor Harold Washington as revenue director, being appointed by Mayor Washington in early 1987.[26][30][31] While in the middle of his 1987 re-election campaign, Washington appointed Quinn to oversee a revenue department which had become scandal-ridden. However, Quinn did not last long in the position, and was dismissed by Washington from this position in June 1987. Quinn alleged that Washington's administration had fought against his efforts to reform the troubled department.[32]

Around this time, Quinn served on the local school council of Sayre Magnet School on Chicago's West Side.[33] Quinn After the death in office of Cook County Board of Appeals commissioner Harry H. Semrow, Quinn considered running in the special election (held in 1988) to fill Semrow's seat.[32]

Term as state treasurer (1991–1995) and 1994 secretary of state campaign

[edit]Quinn won the 1990 election for Illinois treasurer, defeating Peg McDonnell Breslin in the Democratic primary and Greg Baise in the general election.[34][35] Quinn campaigned as a populist reformer in opposition to big government.[33]

He pledged during his campaign that he would seek to transform the office into a consumer advocate-style position.[33] As a candidate, he refused to take campaign contributions from banking officials.[33] He also pledged as a candidate to modernize the office and maximize returns on state deposits through use of electronic fund transfers and through expanding linked-deposit programs.[33] He released an "Invest in Illinois" plan which proposed competitive bidding from financial institutions wanting to be state depositories.[33] He also promised that he would not deposit or invest assets used to pay employee retirement benefits in junk bonds.[33] He also pledged to implement a professional code of ethics for the office's employees.[33]

He served in the position of Illinois Treasurer from 1991 to 1995. During this period, he was publicly critical of Illinois Secretary of State and future governor, George Ryan. Specifically, he drew attention to special vanity license plates that Ryan's office provided for cronies and the politically connected. This rivalry led Quinn to unsuccessfully challenge Ryan in the 1994 general election for Secretary of State, winning the Democratic primary but losing in the general.[36][37]

1996 U.S. Senate campaign

[edit]Quinn then took his aspirations to the national stage. When United States Senator Paul Simon chose not to seek re-election in 1996, Quinn entered the race. However Dick Durbin won the Democratic primary and eventually the Senate seat.[38]

1998 lieutenant gubernatorial campaign

[edit]Quinn sought the Democratic nomination for lieutenant governor in 1998, but was narrowly defeated by Mary Lou Kearns. Quinn did not initially accept the count and charged fraud, but several weeks after the election he declined to ask the Illinois Supreme Court for a recount and endorsed Kearns.

In 1998, Quinn protested an increase in state legislators' salaries by urging citizens to send tea bags to the governor, Jim Edgar. The tactic was a reference to the Boston Tea Party.[39] As lieutenant governor, he would later repeat this tactic in 2006, urging consumers to include a tea bag when paying their electricity bills, to protest rate hikes by Commonwealth Edison.[40]

Lieutenant governor

[edit]

Quinn won the Democratic nomination for lieutenant governor in March 2002, and subsequently won the general election on the Democratic ticket alongside gubernatorial nominee, Rod Blagojevich. In Illinois, candidates for lieutenant governor and governor at that time ran in separate primary elections, but were conjoined as a single ticket for the general election.[22] This same ticket won re-election in 2006, where Quinn was unopposed in the primary.[23] While Lieutenant Governor, according to his official biography, his priorities were consumer advocacy, environmental protection, health care, broadband deployment, and veterans' affairs.[41]

On December 14, 2008, when Quinn was asked about his relationship with Blagojevich, he said, "Well, he's a bit isolated. I tried to talk to the Governor, but the last time I spoke to him was in August of 2007. I think one of the problems is the Governor did sort of seal himself off from all the statewide officials ... Attorney General Madigan and myself and many others."[42] Blagojevich had announced in 2006 that Quinn was not to be considered part of his administration.[43]

Governor of Illinois (2009-2015)

[edit]Succession and elections

[edit]On January 29, 2009, Rod Blagojevich was removed from office by a vote of 59–0 by the Illinois State Senate.[44] Quinn became Governor of Illinois.[45]

2010 gubernatorial election

[edit]In the Democratic primary for governor in 2010, Quinn defeated State Comptroller Daniel Hynes with 50.4% of the vote.[46] On March 27, 2010, Illinois Democratic leaders selected Sheila Simon to replace Scott Lee Cohen on the ballot, after Cohen won the February 2010 Democratic primary to be Illinois' Lieutenant Governor, but later withdrew amid controversies involving his personal life.[47] In the general election Quinn's campaign aired television ads produced by Joe Slade White that repeatedly asked the question of his opponent, "Who is this guy?"[48] Ben Nuckels was the general election Campaign Manager and was named a "Rising Star of Politics" by Campaigns & Elections magazine for his efforts with Quinn.[49]

Quinn won the general election on November 2, 2010, by a narrow margin against Republican candidate Bill Brady. 47% to 46% [50] Quinn's victory was named by RealClearPolitics.com as the No. 5 General Election upset in the country; Politico said it was the 7th closest gubernatorial in American history.[51]

2014 gubernatorial election

[edit]Quinn declared a run for re-election for 2014.[52] In the summer of 2013, former White House Chief of Staff and former United States Secretary of Commerce William M. Daley declared a run for governor in the Democratic Primary against Quinn, but later dropped out.[53][54] Quinn chose Paul Vallas, the former Chicago Public Schools CEO, as his running-mate.[55] Quinn was challenged in the Democratic Primary by Tio Hardiman, the former director of CeaseFire, but won 72% to 28% and faced Republican businessman Bruce Rauner for the general election.

The majority of major Illinois newspapers endorsed Rauner,[56] but Quinn was endorsed by the Chicago Defender,[57] the Rockford Register Star,[58] and The Southern Illinoisan.[59]

Quinn was defeated by Rauner in the general election, 50% to 46%. He lost every county except Cook County. His term as governor ended on January 12, 2015.

Tenure

[edit]As governor, Quinn faced a state with a reputation for corruption—the two previous governors both went to federal prison—and after two years polls showed Quinn himself was the "Nation's most unpopular governor."[60] The main issue was a fiscal crisis in meeting the state's budget and its long-term debt as the national economic slump continued and Illinois did poorly in terms of creating jobs. Quinn spoke often to the public and met regularly with state leaders, in stark contrast to Rod Blagojevich's seclusion from others. On August 20, 2013 Quinn signed a bill into law that raised the rural interstate speed limit in Illinois to 70 mph. It was previously 65 mph. The bill also raised the speed limit on the Illinois Toll Road. The law became effective at midnight January 1, 2014.

Budget, debt, and taxes

[edit]Quinn announced several "belt-tightening" programs to help curb the state deficit. In July 2009, Quinn signed a $29 billion capital bill to provide construction and repair funds for Illinois roads, mass transit, schools, and other public works projects. The capital bill, known as "Illinois Jobs Now!", was the first since Governor George H. Ryan's Illinois FIRST plan, which was enacted in the late-1990s.[61] On July 7, 2009, he for the second time in a week vetoed a budget bill, calling it "out of balance", his plan being to more significantly fix the budget gap in Illinois.[62] In March 2009, Quinn called for a 1.5 percentage point increase in the personal income tax rate. To help offset the increased rate, he also sought to triple the amount shielded from taxation (or the "personal exemption") – from $2,000 per person to $6,000.[63] However, the bill that eventually passed increased the personal income tax by 2%.

With the state budget deficit projected to hit $15 billion in 2011, the legislature in early 2011 raised the personal income tax from 3% to 5%, and the corporation profits tax 4.8% to 7%. Governor Quinn's office projected the new taxes will generate $6.8 billion a year, enough to balance the annual budget and begin reducing the state's backlog of about $8.5 billion in unpaid bills.[64] A report from the Civic Federation in September 2011 projected a $8.3 billion deficit to end the budget year.[65]

After three years of tax increases for workers and businesses, ending with an increase in corporate taxes in 2011 from 5% to 7%, the national recession left the economy in trouble. During an annual budget address on February 22, 2012 to the Illinois Legislature, Quinn warned that the state's financial system was nearing collapse.[66][67] The Associated Press reported that Quinn feared Illinois was "on the verge of a financial meltdown because of pension systems eating up every new dollar and health care costs climbing through the roof."[68] According to the Civic Federation, Illinois is only able to remain solvent by not paying its bills on time.[67] Quinn advocated Medicaid and healthcare cuts totaling $1.6 billion in 2012; critics including Democratic State Representative Mary E. Flowers stated the cuts would remove hundreds of thousands of the poor and elderly from public health programs.[69] The unprecedented cuts were too small to resolve the long-term issue according to rating agencies that downgraded Illinois to the lowest credit rating of any US state in 2012. As of November 2012, unpaid pension obligations totaled $85 billion with a backlog of $8 billion.[70]

In an effort to reduce the state's financial obligations, in November 2012 Quinn cancelled contracts with the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees. Union officials contended that "Quinn wanted concessions so deep that they are an insult to every state employee," while the administration contended that the state is paying salaries and benefits at levels that "exceed the salaries and benefits of other unionized state workers across the country."[70] As of December 2012, Illinois had the fifth highest unemployment rate in the United States, and by March 2013, Illinois public-employee pension liability reached $100 billion.[71][72]

Pat Quinn has been a major supporter of the controversial Illiana Expressway.[73]

In 2009, Quinn signed into law the Video Gaming Act which legalized the use of video gambling machines in Illinois. Quinn had previously denounced video gambling as a "bad bet". Quinn said the legislation was necessary to make up revenue due to the recession. A 2019 ProPublica investigation found that Illinois gambling regulators were underfunded and understaffed, and the gambling failed to meet projected revenues for the state's public coffers.[74]

Ethics reform and corruption allegations

[edit]On January 5, 2009, Quinn appointed Patrick M. Collins to chair the Illinois Reform Commission, which was tasked with making recommendations for ethical reform for Illinois government.[75][76]

On February 20, 2009, Quinn called for the resignation of US Senator Roland Burris, the man appointed to the United States Senate by Blagojevich to fill the vacant seat created by the resignation of Barack Obama. He changed his position, however, following pressure from prominent African Americans who threatened electoral repercussions.[77]

On March 3, 2009, the Associated Press reported that Quinn had "paid his own expenses" many times as lieutenant governor, contradicting Blagojevich's accusations against Quinn.[78][79] As a rule, he either paid his own way, or stayed at "cut rate hotels" (such as Super 8), and never charged the state for his meals.[79][80]

In June 2009, Quinn launched a panel, chaired by Abner Mikva, to investigate unethical practices at the University of Illinois amid fears that a prior investigation would be ineffective in instituting necessary reforms. The panel was charged with searching the admissions practices, amid reports that the public university was a victim of corruption.[81] The panel found evidence of favoritism and its investigation culminated in the resignation of all but two University trustees.[82]

In Spring 2014, federal prosecutors and the Illinois Legislative Audit Commission launched an investigation into Quinn's $55 million Neighborhood Recovery Initiative, a program launched weeks before 2010 election.[83][84]

On October 22, a federal judge appointed an independent monitor to oversee hiring at the Illinois Department of Transportation. This followed a three-year investigation by the Illinois executive inspector general that uncovered politically motivated hiring at IDOT, which started under Gov. Blagojevich.[85][86]

Environment and energy

[edit]

Quinn won generally high praise for his leadership on environmental issues, going back at least as far as when he was lieutenant governor, where he helped develop annual statewide conferences on green building, created a state day to celebrate and defend rivers,[87] and promoted measures such as rain gardens for water conservation. As governor, Quinn helped pass measures on solar and wind energy,[88] including sourcing electricity for the state capitol from wind power, and helped secure funding for high-speed rail in the midwest corridor. As Governor and Lt. Governor, Quinn Co-Chaired the Illinois Green Government Council, a council that focused on greening state government and reducing waste. The Illinois Green Government Council produced public annual sustainability reports tracking overall state government energy usage, fuel usage, water usage, and waste [89] In 2010 and 2014, the Sierra Club, Illinois's largest environmental group, endorsed Quinn, calling him "The Green Governor."[90][91] Quinn faced protests and strong opposition from environmentalists after his support for a controversial law to regulate and launch fracking.

Social issues

[edit]On March 9, 2011, Quinn signed the bill which abolished the death penalty in Illinois.[92] On signing the bill, Quinn stated,

"It is impossible to create a perfect system, one that is free of all mistakes, free of all discrimination with respect to race or economic circumstance or geography. To have a consistent, perfect death penalty system, I have concluded, after looking at everything I've been given, that that's impossible in our state. I think it's the right and just thing to abolish the death penalty."[93]

In an interview with The New York Times, Quinn attributed his decision to the late Cardinal Joseph Bernardin who had argued until the end of his life for a “consistent ethic of life" that included opposing capital punishment. To date, capital punishment is still outlawed in Illinois.[94] In 2011, Quinn received the Courageous Leadership Award from Death Penalty Focus.[95]

On May 17, 2012, Quinn appointed Brandon Bodor to be Executive Director of the Serve Illinois Commission. On September 11, 2012, the two announced that the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS) had awarded $8.4 million to enable 1,200 volunteers in 29 AmeriCorps programs to better serve Illinois communities.[96]

Quinn is an advocate for gun control, supporting an assault weapons ban, high-capacity magazine ban and universal background checks for Illinois.[97] Quinn has also been known for criticizing concealed carry legislation in Illinois (which would allow a person to have a concealed handgun on their person in public), and the National Rifle Association of America.[98] Despite this opposition, the Illinois General Assembly legalized concealed carry in the state on July 9, 2013, overriding Quinn's veto. This made Illinois the last state in the U.S. to enact this type of legislation.[99]

In Quinn's 2013 State of the State address, he declared his commitment to the legalization of same sex marriage.[100] After a months-long battle in the legislature, Quinn signed the Religious Freedom and Marriage Fairness Act into law[101] on November 20, 2013, before a crowd of thousands, making Illinois the 16th state in the nation to legalize same-sex marriage.[102] He had previously signed a bill legalizing civil unions on January 31, 2011.[103]

Post-gubernatorial activities

[edit]

Quinn has kept a low profile since leaving office, volunteering for causes like veterans' affairs and consumer protection.[104] Quinn has been critical of his successor, Bruce Rauner, calling him "anti-worker" and "dishonest." He has stated that he is interested in grassroots petitions.[105]

On June 12, 2016, Quinn announced a new petition drive called Take Charge Chicago to put a binding referendum on the Chicago ballot to place a two-term limit on the Mayor of Chicago and create a new elected position called the Consumer Advocate.[106][107] As of mid-2017, that is still ongoing.

On October 27, 2017, Quinn announced he would run for Illinois Attorney General in the 2018 election.[2] Quinn was generally regarded as the most well-known candidate in the race,[108] however he narrowly lost the nomination to State Senator Kwame Raoul on March 20, 2018.

For the 2020 election cycle, Quinn championed a citizens initiated ballot item which would ask voters in Evanston whether they believed that the city should adopt a system under which binding citizen initiated referendums to create city ordinances would be allowed. This ballot question was rejected by the city's election board, a decision subsequently upheld in the Circuit Court of Cook County and the Illinois Appeals Court.[109][110]

During the 2023 Chicago mayoral election, Quinn flirted with the idea of running for Chicago mayor, going as far as collecting signatures to appear on the ballot.[111] However, he declined to run in the election and subsequently endorsed U.S. Representative Chuy Garcia's candidacy in the first round of voting,[112] and then his former running mate Paul Vallas in the run-off.[113]

Electoral history

[edit]For Illinois Attorney General

[edit]| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Kwame Raoul | 374,667 | 30.2 | |

| Democratic | Pat Quinn | 340,163 | 27.4 | |

| Democratic | Sharon Fairley | 156,070 | 12.6 | |

| Democratic | Nancy Rotering | 115,974 | 9.3 | |

| Democratic | Scott Drury | 98,246 | 7.9 | |

| Democratic | Jesse Ruiz | 67,706 | 5.5 | |

| Democratic | Renato Mariotti | 49,891 | 4.0 | |

| Democratic | Aaron Goldstein | 37,987 | 3.1 | |

| Total votes | 1,159,701 | 100 | ||

As Governor of Illinois (with Lt. Governor)

[edit]2014

[edit]| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Bruce Rauner/Evelyn Sanguinetti | 1,823,627 | 50.27 | |

| Democratic | Pat Quinn/Paul Vallas (Incumbent) | 1,681,343 | 46.35 | |

| Libertarian | Chad Grimm/Alex Cummings | 121,534 | 3.35 | |

| Write-In | Various candidates | 1,186 | 0.03 | |

| Majority | 142,284 | 3.92% | ||

| Total votes | 3,627,690 | 100 | ||

| Republican gain from Democratic | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Pat Quinn (Incumbent) | 321,818 | 71.94 | |

| Democratic | Tio Hardiman | 125,500 | 28.06 | |

| Total votes | 447,318 | 100 | ||

2010

[edit]| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Pat Quinn (Incumbent) | 1,745,219 | 46.79% | −3.00% | |

| Republican | Bill Brady | 1,713,385 | 45.94% | +6.68% | |

| Independent | Scott Lee Cohen | 135,705 | 3.64% | ||

| Green | Rich Whitney | 100,756 | 2.70% | −7.66% | |

| Libertarian | Lex Green | 34,681 | 0.93% | ||

| Majority | 31,834 | 0.85% | −9.68% | ||

| Turnout | 3,729,989 | ||||

| Democratic hold | Swing | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Pat Quinn (Incumbent) | 462,049 | 50.46 | |

| Democratic | Dan Hynes | 453,677 | 49.54 | |

| Total votes | 915,726 | 100.00 | ||

As Lt. Governor (with Governor)

[edit]- 2006 Election for Governor/Lieutenant Governor of Illinois[118]

- Rod Blagojevich/Pat Quinn (D) (inc.), 49.79%

- Judy Baar Topinka/Joe Birkett (R), 39.26%

- Rich Whitney/Julie Samuels (Green), 10.36%[citation needed]

- 2002 Election for Governor / Lieutenant Governor

- Rod Blagojevich/Pat Quinn (D), 52%

- Jim Ryan/Carl Hawkinson (R), 45%

For Illinois Secretary of State

[edit]- 1994 – Illinois Secretary of State

- George Ryan (R) (inc.)[34] 61.5%

- Pat Quinn (D) 38.5%

For state treasurer

[edit]- 1990 – Illinois Treasurer[34]

- Pat Quinn (D) 55.7%

- Greg Baise (R) 44.3%

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Jerry Cosentino | 241,006 | 30.22 | |

| Democratic | James H. Donnewald (incumbent) | 235,052 | 29.47 | |

| Democratic | Patrick Quinn | 208,775 | 26.18 | |

| Democratic | Robert D. Hart | 112,645 | 14.13 | |

| Write-in | Others | 1 | 0.00 | |

| Total votes | 797,478 | 100 | ||

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Pat Quinn - The Man Politicians Love to Hate". Illinois Times. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ a b Sneed, Michael (October 27, 2017). "SNEED EXCLUSIVE: Ex-Gov. Pat Quinn to run for state attorney general". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ Saulny, Susan (January 30, 2009). "Successor in Illinois Is the Anti-Blagojevich". New York Times. Retrieved January 22, 2025.

- ^ Ormsby, David (November 4, 2010). "Progressive, Conservative and Tea Party Voters Help Hand Governor Pat Quinn Victory". Retrieved January 22, 2025.

- ^ "Can't Pat Quinn Get Any Respect?". Chicago Magazine. February 11, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2025.

- ^ Tareen, Sophia (November 19, 2013). "Illinois governor signs same-sex marriage into law". State Journal-Register. Retrieved January 22, 2025.

- ^ Freedman, Samuel G. (March 25, 2011). "Faith Was on the Governor's Shoulder". New York Times. Retrieved January 22, 2025.

- ^ "Bruce Rauner ousts Illinois Gov. Pat Quinn". Politico.com. November 4, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ Korecki, Natasha (January 7, 2015). "Quinn gets emotional during farewell address". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ Michael Barone and Chuck McCutcheon, The Almanac of American Politics: 2012 (2011) p. 512.

- ^ "Pat Quinn's mom shows toughness, love on the campaign trail". Daily Herald. November 6, 2010.

- ^ "Death Notice: PATRICK J. QUINN SR". Chicago Tribune. February 26, 2008.

- ^ "Pat Quinn - Illinois Issues - A Publication of the University of Illinois at Springfield - UIS". uis.edu. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ Pat Quinn: Notepad. YouTube. October 25, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ Joravsky, Ben (April 23, 1987). "City Hall's bill collector: Pat Quinn has a deal for you". Chicago Reader. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ Coalition for Political Honesty v. State Bd. of Elections, 65 Ill.2d 453,359 N.E.2d 138,3 Ill.Dec. 728 (Illinois Supreme Court Dec. 3, 1976).

- ^ Thompson, James (August 20, 2014). "Interview with James Thompson #IST-A-L-2013-054.10" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by DePue, Mark. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ Coalition for Pol. Honesty v. State Bd. of Elec. (1980), Text.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

ilga1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

ISOSHORAwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "OFFICIAL VOTE Cast at the GENERAL ELECTION NOVEMBER 4, 1980" (PDF). www.elections.il.gov. Illinois State Board of Elections. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Quinn Would Face $2 Billion Budget Gap as Blagojevich Successor". Bloomberg News. December 15, 2008. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ^ a b Political Base. "Pat Quinn – Issues, Money, Videos".

- ^ "Celebrating 40 years of consumer advocacy!". Citizens Utility Board. Retrieved February 4, 2025.

- ^ Joravsky, Ben (December 24, 1987). "Special Election: a Reformer Runs for the County Board of Tax Appeals". Chicago Reader.

- ^ a b Berkman, Harvey (August 1990). "Electing Illinois' Other Executives". Illinois Issues. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ West, Harry G.; Sanders, Todd (April 17, 2003). "Transparency and Conspiracy: Ethnographies of Suspicion in the New World Order". Duke University Press. p. 224. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ Neal, Steve (June 12, 1986). "COSENTINO: NEVER ONE TO DUCK A FIGHT". chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ Devall, Cheryl (October 14, 1986). "COSENTINO`S EDGE CUTS BOTH WAYS". chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ Hawthorne, Michael (December 10, 2008). "Pat Quinn Waiting in the Wings". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 30, 2009.

- ^ "Biographical information on Quinn". WTOP.com. Associated Press. January 29, 2009. Retrieved January 30, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Race Begins to Fill Vacancy On Tax Appeals Board". Chicago Tribune. November 25, 1987. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Guy, Sandra (October 14, 1990). "Illinois election 1990. Candidate profiles. Illinois state". nwitimes.com. The Times of Northwest Indiana.

- ^ a b c Illinois Blue Book

- ^ Watson, Angie (April 1990). "Election 1990: Quinn prevails; incumbents upset". Illinois Issues. Vol. 15, no. 4. Springfield, Illinois: Sangamon State University. p. 9. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- ^ "State of Illinois official vote cast at the primary election held on ..." Illinois State Board of Elections. 1966. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ "State of Illinois official vote cast at the general election ." Illinois State Board of Elections. 1978. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ Neal, Steve (December 12, 1995). "Outsider Quinn Vows to Look Out for the 'Little Guy'". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2009.

- ^ Selvam, Ashok (April 14, 2009), "Quinn tackles income tax plan, gay marriage during Harper visit", Daily Herald, retrieved February 2, 2010

- ^ Duncanson, Jon (September 18, 2006). "Quinn Wants Boston Tea Party Revolt Against ComEd". CBS Broadcasting, Inc. Retrieved February 1, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Lt. Governor Pat Quinn". Standing Up for Illinois. November 7, 2006. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ Gregory, David (December 14, 2008). "'Meet the Press' transcript for Dec. 14, 2008". NBC News. Retrieved January 30, 2009.

- ^ Burton, Cheryl (December 15, 2008). "Quinn alters his plan for governor". WLS-TV. Retrieved January 30, 2009.

- ^ Long, Ray; Rick Pearson (January 30, 2009). "Impeached Illinois Gov. Rod Blagojevich has been removed from office". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- ^ Barone and McCutcheon, The Almanac of American Politics: 2012 (2011) p 513

- ^ "Chicago Tribune – Election Results". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- ^ "Democrats pick Simon as Quinn's running mate". Chicago Tribune. March 27, 2010.

- ^ "Quinn, Brady neck and neck in new Tribune poll". Chicago Tribune. September 30, 2010.

- ^ "Campaigns & Elections Names 2011 Class of Rising Stars". Campaigns & Elections Magazine. June 6, 2011. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012.

- ^ Pearson, Rick; Long, Ray (November 5, 2010). "Republican Bill Brady concedes governor's race to Quinn". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ "Top 10 Upsets of 2010 – 5. IL Gov: Pat Quinn Hangs On". RealClearPolitics. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ^ "Quinn Running Again Because "I Think I'm Doing A Good Job"". NBC Chicago. November 29, 2012. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ "Bill Daley jumps '100 percent' in Illinois governor race". Chicago Sun-Times. June 10, 2013. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ "Bill Daley drops bid for governor". Chicago Tribune. September 16, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ Burnett, Sara. "Quinn picks Paul Vallas as 2014 running mate". Pantagraph. Associated Press. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ Merda, Chad (October 14, 2014) - "Who's Winning the Endorsement Battle in Illinois?" Archived November 11, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ (October 27, 2014) - "The Quintessential Choice for Governor: The Chicago Defender Endorses Pat Quinn for Governor" Archived December 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. The Chicago Defender. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ (October 26, 2014) - "Our View: In Illinois Governor's Race, Pat Quinn is Right Pick for Rockford". Rockford Register Star. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ (October 29, 2014) - "Governor: The Devil You Know". The Southern Illinoisian. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ "Pat Quinn, Illinois Governor, Polls As Nation's Least Popular Governor". Huffington Post. November 30, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ^ Ferkenhoff, Eric (December 16, 2008). "Pat Quinn: The Man Who Would Replace Blagojevich". Time. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- ^ Garcia, Monique (July 8, 2009). "Gov. Quinn shifts gears on cutbacks and vetoes budget". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ^ Long, Ray; Ashley Rueff (March 13, 2009). "Illinois income tax rate may rise by 50%". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 22, 2010.

- ^ "Ill. Gov. Quinn signs major tax increase into law," Associated Press January 13, 2011

- ^ Garcia, Monique (September 26, 2011). "Illinois budget deficit to hit $8 billion despite tax increase". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- ^ "Quinn's speech vague on major Illinois budget problems". Associated Press. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Hal Weitzman, Nicole Bullock (March 5, 2012). "Financial Times". Financial Times. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ^ Christopher Wills, "Quinn says hello to 'reality' in Illinois," Associated Press Feb. 23, 2012

- ^ Ray Long and Alissa Groeninger (May 25, 2012). "Illinois Legislature passes $1.6 billion in Medicaid cuts". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ^ a b The Associated Press (November 20, 2012). "Quinn Terminates Contract With State's Largest Worker Union". CBS Chicago. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ^ Frum, David. "Welcome to Botswana". The Daily Beast. Newsweek. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ^ Goudie, Chuck. "Quinn faces daunting State of State as Illinois struggles". WLS-TV. ABC. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ^ Quinn underlines support for Illiana Expressway

- ^ Grotto, Jason; Kambhampati, Sandhya (January 16, 2019). "Illinois Bet on Video Gambling — and Lost". ProPublica. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ "Illinois Ethics Reform: Panel Releases Report of Recommendations," Chicago Tribune, April 29, 2009, found at Chicago Tribune website Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ "Illinois Reform Commission – Mission". Reformillinoisnow.org. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ^ Long, Ray; Ashley Rueff (April 6, 2009). "Burris election off the table". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- ^ "Ill. Gov Quinn mostly paid his own way," USA Today, March 3, 2009, at 3A, found at USA Today website. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ a b John O'Connor, "AP review shows new Ill. governor often paid own travel expenses instead of charging taxpayers, AP and Chicago Tribune, March 3, 2009, found at Chicago Tribune website. Retrieved March 4, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "Report: Quinn eschewed tax dollars for meals, travel," ABC Affiliate WLS-TV, Tuesday, March 3, 2009, found at ABC website. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ Malone, Tara; Stacy St. Clair (June 11, 2009). "University of Illinois clout: Gov. Pat Quinn gives clout-list panel its marching orders". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- ^ "Report & Recommendations" (PDF). State of Illinois Admissions Review Commission. August 7, 2009. Retrieved October 25, 2009.

- ^ Peters, Mark (July 16, 2014). "Illinois Gov. Pat Quinn's Re-Election Hampered by Criminal Investigation". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ Long, Rick (October 9, 2014). "Emails reveal politics part of troubled Quinn grant program". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ "Governor Quinn, clean house". Chicago Tribune. September 15, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ Garcia, Monique (October 22, 2014). "Federal judge deals Quinn ethics blow on IDOT patronage hiring". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ "It's Our River Day". Environmental Defenders of McHenry County. January 29, 2010. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ "Governor Pat Quinn signs green bills into law at 2009 Sustainable University Symposium" (Press release). Palos Hills: Illinois Government News Network. July 24, 2009. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ^ "Green.illinois.gov". Archived from the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2017.

- ^ "YouTube – The Green Governor – Pat Quinn". Sierra Club IL PAC. January 29, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ "Governor Quinn endorsed by Illinois Sierra Club". FOX2now.com. September 20, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ "Illinois Abolishes Death Penalty, Clears Death Row". NPR. March 9, 2011. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ "Illinois Abolishes Death Penalty". Democracy Now!. March 10, 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ Freedman, Samuel G. (March 25, 2011). "The Death Penalty and Cardinal Bernardin — On Religion". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2019.(subscription required)

- ^ News |, Daily (May 12, 2011). "Illinois governor to be honored in Beverly Hills tonight by death penalty opponents". Daily News. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ ENews Park Forest. "Governor Quinn And 'Serve Illinois Commission' Announce $8.4 Million Federal Grant For AmeriCorps Programs". ENews Park Forest. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ "Pat Quinn on Gun Control". On The Issues. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ^ "Quinn says he's ready for 'showdown' on concealed carry". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on July 10, 2013. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ^ "Illinois enacts nation's final concealed-gun law". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 10, 2013. Retrieved July 23, 2015./

- ^ "Governor Quinn Delivers 2013 State of the State Address" (Press release). Springfield, Illinois. Illinois Government News Network. February 6, 2013. Archived from the original on February 19, 2013. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ "Illinois governor signs same-sex marriage into law". CBS News. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ Garcia, Monique (November 20, 2013). "Quinn signs Illinois gay marriage bill". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "Illinois civil unions signed into law". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- ^ Bazer, Mark (May 6, 2016). "Pat Quinn". The Interview Show. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- ^ Fortino, Ellyn (January 14, 2016). "Quinn Slams Rauner Over Ongoing Budget Impasse". Progress Illinois. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ^ Hinz, Greg (June 12, 2016). "Quinn pushes referendum to term limit Emanuel". Crain's Chicago Business. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- ^ Dietrich, Matt. "Pat Quinn gets back into action with Chicago term limits, elected Consumer Advocate Push". Reboot Illinois. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ "Meet the 8 Democrats hoping to replace Lisa Madigan as attorney general". WGN-TV. March 6, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ Bookwalter, Genevieve (January 16, 2020). "Binding referendum initiative backed by former Gov. Pat Quinn struck down by Evanston electoral board". chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Bill (March 16, 2020). "Appeals court upholds objections to referendum". Evanston Now. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ Spielman, Fran (November 17, 2022). "Former Gov. Pat Quinn decides to skip mayor's race". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ "Former Illinois Gov. Pat Quinn endorses Garcia for mayor". Chicago Sun-Times. February 8, 2023.

- ^ "Quinn endorsing Vallas". Politico. March 22, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ "November 4, 2014 General election Official results" (PDF). Illinois Secretary of State. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 28, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ^ Official Illinois State Board of Elections Results Archived January 28, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "General Election of November 2, 2010" (PDF). Illinois State Board of Elections. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 27, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ "Ballots Cast (primary election)". Elections.illinois.gov. Archived from the original on August 14, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ^ "2007–2008 Illinois Blue Book" (PDF). Illinois General Election November 7, 2006 Summary of General Vote (page 466). Office of Jesse White, Illinois Secretary of State. 2007–2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2011. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

PEwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Further reading

[edit]- Barone, Michael, and Chuck McCutcheon, The Almanac of American Politics: 2012 (2011) pp 512–14

External links

[edit]- Illinois Governor Pat Quinn official Illinois government site

- Pat Quinn campaign website

- Pat Quinn for Governor

- Appearances on C-SPAN