Peter Sutcliffe | |

|---|---|

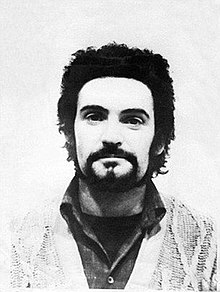

Sutcliffe after his arrest in Sheffield, 1981 | |

| Born | Peter William Sutcliffe 2 June 1946 Bingley, West Riding of Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 13 November 2020 (aged 74) Brasside, County Durham, England |

| Other names |

|

| Occupation | HGV driver |

| Height | 5 ft 8 in (1.73 m)[1] |

| Criminal status | Died in prison |

| Spouse | |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment (whole life order) |

| Details | |

| Victims | 22+ (13 confirmed murdered, 7 confirmed injured, 2 suspected to be injured, at least 1 other officially suspected murder) |

Span of crimes | 1975–1980 (confirmed) |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Location(s) | |

Date apprehended | 2 January 1981 |

| Imprisoned at |

|

Peter William Sutcliffe (2 June 1946 – 13 November 2020), also known as Peter Coonan, was an English serial killer who was convicted of murdering thirteen women and attempting to murder seven others between 1975 and 1980.[2]: 144 He was dubbed in press reports as the Yorkshire Ripper, an allusion to the Victorian serial killer Jack the Ripper. He was sentenced to twenty concurrent sentences of life imprisonment, which were converted to a whole life order in 2010. Two of Sutcliffe's murders took place in Manchester; all the others were in West Yorkshire. Criminal psychologist David Holmes characterised Sutcliffe as being an "extremely callous, sexually sadistic serial killer."[3]

Sutcliffe initially attacked women and girls in residential areas, but appears to have shifted his focus to red-light districts because he was attracted by the vulnerability of prostitutes and the perceived ambivalent attitude of police to prostitutes' safety.[4][5] After his arrest in Sheffield by South Yorkshire Police for driving with false number plates in January 1981, he was transferred to the custody of West Yorkshire Police, who questioned him about the killings. Sutcliffe confessed to being the perpetrator, saying that the voice of God had sent him on a mission to kill prostitutes. At his trial he pleaded not guilty to murder on grounds of diminished responsibility, but he was convicted of murder on a majority verdict. Following his conviction, Sutcliffe began using his mother's maiden name of Coonan.

The search for Sutcliffe was one of the largest and most expensive manhunts in British history. West Yorkshire Police faced heavy and sustained criticism for their failure to catch him despite having interviewed him nine times in the course of their five-year investigation. Owing to the sensational nature of the case, the police handled an exceptional amount of information, some of it misleading including hoax correspondence purporting to be from the "Ripper". Following Sutcliffe's conviction, the government ordered a review of the investigation, conducted by the Inspector of Constabulary Lawrence Byford, known as the "Byford Report". The findings were made fully public in 2006, and confirmed the validity of the criticism of the force.[6] The report led to changes to investigative procedures that were adopted across UK police forces.[7] Since his conviction, Sutcliffe has been linked to a number of other unsolved crimes.

Sutcliffe was transferred from prison to Broadmoor Hospital in March 1984 after being diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia.[8] The High Court dismissed an appeal by Sutcliffe in 2010, confirming that he would serve a whole life order and never be released from custody. In August 2016, it was ruled that he was mentally fit to be returned to prison, and he was transferred that month to HM Prison Frankland. Sutcliffe died in the hospital from diabetes-related complications while in prison custody in 2020.

Early life

[edit]Peter William Sutcliffe was born on Sunday, 2 June 1946 to a working-class family in Bingley, West Riding of Yorkshire. His parents were John William Sutcliffe (1922–2004) and his Irish wife Kathleen Frances Coonan (1919–1978), a native of Connemara.[9] Kathleen was a Roman Catholic and John was a member of the choir at the local Anglican church of St Wilfred's; their children were raised in their mother's Catholic faith, and Sutcliffe briefly served as an altar boy.[10] Sutcliffe was a premature baby, having to spend two weeks in hospital, and his mother was the victim of domestic abuse, making it likely she struggled through her pregnancy under great emotional stress.[11]

Sutcliffe's father was a heavy drinker who once smashed a beer glass over Sutcliffe's head for sitting in his chair at the Christmas table.[12] John Sutcliffe also hated his mother: "She was a bitch and the least said about her, the better."[13] He would frequently dismiss the slightly built Sutcliffe as "a wimp, always hanging from his mother's apron, a mummy's boy." Sutcliffe's mother often lavished attention on her son, and was to become seen by Sutcliffe as "perfect". Sutcliffe's father would also whip his children with a belt as a form of punishment.[14] Sutcliffe's siblings later described their father as "a monster" and, according to Sutcliffe's younger brother, "The atmosphere in our house would change as soon as he [John] walked in. His life revolved around playing football, cricket, singing in a choir—and womanising."[14]

In 1970, Sutcliffe's father posed as his wife's lover in order to lure her to a local hotel and took Sutcliffe and two of his siblings to witness him expose her infidelity. When Kathleen arrived, Sutcliffe's father pulled out a negligee from his wife’s purse as her children watched. In his late-adolescence, Sutcliffe developed a growing obsession with voyeurism, and spent much time spying on prostitutes and the men seeking their services.[15] Reportedly a loner, Sutcliffe left school at the age of 15 and had a series of menial jobs, including two stints as a gravedigger at Bingley Cemetery in the 1960s.[16] Because of this occupation, he developed a macabre sense of humour — co-workers reported that Sutcliffe enjoyed his work too much and would even volunteer to do overtime washing the corpses.[14] Between November 1971 and April 1973, Sutcliffe worked at the Baird Television factory on a packaging line. He left this position when he was asked to go on the road as a salesman.[2]: 63

After leaving Baird Television, Sutcliffe worked night shifts at the Britannia Works of Anderton International from April 1973. In February 1975, he took redundancy and used half of the £400 pay-off to train as a heavy goods vehicle (HGV) driver.[17] On 5 March 1976, Sutcliffe was dismissed for the theft of used tyres. He was unemployed until October 1976, when he found a job as an HGV driver for T. & W.H. Clark Holdings Ltd. on the Canal Road Industrial Estate in Bradford.[2]: 71 Sutcliffe reportedly hired prostitutes as a young man, and it has been speculated that he had a bad experience during which he was conned out of money by a prostitute and her pimp.[18] Other analyses of his actions have not found evidence that he actually sought the services of prostitutes but note that he nonetheless developed an obsession with them, including "watching them soliciting on the streets of Leeds and Bradford."[15]

Sutcliffe met 16-year-old Sonia Szurma, the daughter of Ukrainian and Polish refugees from Czechoslovakia, on 14 February 1967, at Royal Standard pub on Manningham Lane in Bradford's red light district; they married on 10 August 1974.[19] Sonia was studying to become a teacher when she was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. Her relationship with her husband was later characterised by the writer Gordon Burn as domineering, with Sonia willing to slap him down "like a naughty schoolboy",[20] while her husband even had to occasionally "contain her physically by pinning her arms to her side" during her common "unprovoked outbursts of rage."[21]

Barbara Jones, a journalist who had many conversations with Sonia, described her as "the most irritating, strangest and coldest person I've ever met. She's so incredibly prickly and demanding."[22] Sonia had several miscarriages, and they were informed that she would not be able to have children.[23] She eventually resumed her teacher training course, during which time she had an affair with an ice-cream van driver. When Sonia completed the course in 1977 and began teaching, she and Sutcliffe used her salary to buy a house at 6 Garden Lane in Heaton, into which they moved on 26 September 1977, and where they were living at the time of Sutcliffe's arrest.[24]

Attacks and murders

[edit]1969

[edit]Sutcliffe's first documented assault was of a female prostitute, who he had met while searching for another woman who had tricked him out of money.[25] He left his friend Trevor Birdsall's minivan and walked up St. Paul's Road in Bradford until he was out of sight.[26] When Sutcliffe returned, he was out of breath, as if he had been running; he told Birdsall to drive off quickly. Sutcliffe said he had followed a prostitute into a garage and hit her over the head with a stone in a sock.[27] Police visited Sutcliffe's home the next day, as the woman he had attacked had noted Birdsall's vehicle registration plate.[28] Sutcliffe admitted he had hit her, but claimed it was with his hand.[29] The police told him he was "very lucky", as the woman did not want to press charges.[30]

1975

[edit]Sutcliffe committed his second assault on the night of 5 July 1975 in Keighley. He attacked 36-year-old Anna Rogulskyj, who was walking alone, striking her unconscious with a hammer and slashing her stomach with a knife.[31] Disturbed by a neighbour, he left without killing her. Rogulskyj survived after brain surgery[a] but she was psychologically traumatised by the attack.[32] She later said: "I've been afraid to go out much because I feel people are staring and pointing at me. The whole thing is making my life a misery. I sometimes wish I had died in the attack."[33]

On the night of 15 August, Sutcliffe attacked 46-year-old Olive Smelt in Halifax. Employing the same modus operandi, he briefly engaged Smelt with a commonplace pleasantry about the weather before striking hammer blows to her skull from behind. He then disarranged her clothing and slashed her lower back with a knife. Again he was interrupted and left his victim badly injured but alive. Like Rogulskyj, Smelt subsequently suffered severe emotional and mental trauma. Smelt later told Detective Superintendent Dick Holland that her attacker had a Yorkshire accent but this information was ignored, as was the fact that neither she nor Rogulskyj were in towns with a red light area.[34]

On 27 August, Sutcliffe targeted 14-year-old Tracy Browne in Silsden, attacking her from behind and hitting her on the head five times while she was walking along a country lane. He ran off when he saw the lights of a passing car, leaving his victim requiring brain surgery. Sutcliffe was not convicted of the attack but confessed in 1992. Browne later said that she had been charmed by Sutcliffe at first: "We had walked together for almost a mile – for about 30 minutes and I never once felt intimidated or in danger."[35]

The first victim to be killed by Sutcliffe was 28-year-old Wilma Mary McCann on 30 October. McCann, from Scott Hall, was a mother of four children. Sutcliffe struck the back of her skull twice with a hammer. At 7:30 p.m., she was last seen leaving her council house on Scott Hall Avenue, in the Chapeltown area of Leeds, walking past the nearby Prince Philip Playing Fields.[36] An extensive inquiry, involving 150 officers of the West Yorkshire Police and 11,000 interviews, failed to find the culprit.[b][c]

1976

[edit]Sutcliffe committed his next murder in Leeds on 20 January 1976, when he stabbed 42-year-old Emily Monica Jackson fifty-two times.[38] In dire financial straits, Jackson had been persuaded by her husband to engage in prostitution, using the van of their family roofing business. Sutcliffe picked up Jackson, who was soliciting outside the Gaiety pub on Roundhay Road, then drove about half a mile to some derelict buildings on Enfield Terrace in the Manor Industrial Estate.[39] Sutcliffe hit her on the head with a hammer, dragged her body into a rubbish-strewn yard, then used a sharpened screwdriver to stab her in the neck, chest and abdomen. He stamped on her thigh, leaving behind an impression of his boot.[2]: 30

Sutcliffe attacked 20-year-old Marcella Claxton in Roundhay Park on 9 May. Walking home from a party, she accepted an offer of a lift from Sutcliffe. When she got out of the car to urinate, he hit her from behind with a hammer. Claxton survived and testified against Sutcliffe at his trial. At the time of this attack, Claxton had been four months pregnant and subsequently miscarried her baby.[16] She required multiple, extensive brain operations and had intermittent blackouts and chronic depression.[33]

1977

[edit]On 5 February, Sutcliffe attacked 28-year-old Irene Richardson, a Chapeltown prostitute, in Roundhay Park.[40] Richardson was last seen at 11:15 p.m. leaving a rooming house on Cowper Street, saying she was going to Tiffany's, a pub and disco in the centre of Leeds. Richardson was bludgeoned to death with a hammer and had been stabbed in the neck and throat and three times in the stomach. Once she was dead, Sutcliffe mutilated her corpse with a knife and then arranged her body by neatly placing her knee-length boots over the back of her thighs. Tyre tracks left near the murder scene resulted in a long list of possible suspect vehicles.[2]: 36

Two months later, on 23 April, Sutcliffe killed 32-year-old prostitute Patricia "Tina" Atkinson-Mitra in her Bradford flat, where police found a bootprint on the bedclothes.[41] According to Sutcliffe, he picked Atkinson up in Manningham, Bradford, before driving to her residence. He then hit her on the back of the head four times to incapacitate her. Sutcliffe then pulled down her jeans and pants and exposed her breasts. He then stabbed her six times in the stomach with a knife.

On 25 June 1977, 16-year-old Jayne Michelle MacDonald went to meet friends at the Hofbrauhaus, a German-style bierkeller in Leeds. She missed the last bus home and went back to her friend's house to wait for his sister to bring her home. After 45 minutes or so, she ended up walking home, where she was attacked by Sutcliffe in Reginald Street in Leeds[42] at around 2:00 a.m.[43]: 190 [44] Her body was discovered the following morning at 9:45 a.m. by children in the playground between Reginald Terrace and Reginald Street in Chapeltown. A post mortem exam was carried out by the Home Office pathologist Professor David Gee. The extent of her injuries was not revealed at the time by police, although it was subsequently revealed she had been hit on the head three times with a hammer and had been stabbed in the chest and back. A broken bottle was found embedded in her chest.[45]

The following month, on 10 July 1977, Sutcliffe assaulted 43-year-old Maureen Long in Bradford. Long was leaving a nightclub when Sutcliffe offered her a lift home. Long stopped to urinate and Sutcliffe struck her on the head, knocking her out. Long was suffering from hypothermia when found and was in hospital for nine weeks.[33] A witness misidentified the make of Sutcliffe's car, resulting in more than 300 police officers checking thousands of cars without success.

On 1 October 1977, Sutcliffe murdered 20-year-old Jean Bernadette Jordan, a prostitute and mother-of-two from Manchester known to her friends as "Scottish Jean".[2]: 92 [d] Shortly after 9:00 p.m., Sutcliffe was cruising the area of Moss Side when he picked up Jordan. After they arrived in Princess Road near the Southern Cemetery, Sutcliffe hit Jordan once in the head before proceeding to hit her ten more times. In a later confession, Sutcliffe said he had realised the new five-pound note he had given to Jordan was traceable. After hosting a family party at his new home, he returned to the wasteland behind Manchester's Southern Cemetery, where he had left the body, but he was unable to find the note.

On 9 October, Jordan's body was discovered by local dairy worker and future actor Bruce Jones,[46] who had an allotment on land adjoining the site and was searching for house bricks when he made the discovery. The note, hidden in a secret compartment in Jordan's handbag, was traced to branches of the Midland Bank in Shipley and Bingley. Police analysis of bank operations allowed them to narrow their field of inquiry to 8,000 employees who could have received it in their wage packet. Over three months, the police interviewed 5,000 men, including Sutcliffe. The police found that the alibi given for Sutcliffe's whereabouts, that he had attended a family party, was credible. Weeks of intense investigations pertaining to the origins of the five-pound note led to nothing, leaving investigators frustrated that they collected an important clue but had been unable to trace the actual firm to which or whom the note had been issued.[47]

On 14 December, Sutcliffe attacked Marilyn Moore, a 25-year-old prostitute, in the back of his car on waste ground in Scott Hall, Leeds. Sutcliffe lost his balance whilst delivering a blow to Moore with a hammer allowing Moore to escape with severe head injuries but still alive. Tyre tracks found at the scene matched those from an earlier attack.[16] The resulting photofit bore a strong resemblance to Sutcliffe, as had those from other survivors, and Moore provided a good description of Sutcliffe's car, which had been seen in red light areas. Sutcliffe was interviewed on this issue.[48]

1978

[edit]The police discontinued the search for the person who received the five-pound note in January 1978. Although Sutcliffe was interviewed about the matter, he was not investigated further and was contacted and disregarded by the Ripper Squad on several further occasions. That month, Sutcliffe killed Yvonne Ann Pearson, a 21-year-old prostitute from Bradford, on 21 January 1978. He repeatedly bludgeoned her about the head with a ball-peen hammer, then jumped on her chest before stuffing horsehair into her mouth from a discarded sofa, under which he hid her body near Lumb Lane.[2]: 107

Ten days later, on 31 January, Sutcliffe killed Elena "Helen" Rytka, an 18-year-old prostitute from Huddersfield, striking her on the head five times as she exited his vehicle at Garrards timber yard before stripping most of the clothes from her body, although her bra and polo-neck jumper were positioned above her breasts. Rytka was then sexually assaulted as she lay on the ground. She was the only one of his victims that he had sexual intercourse with.[49] After Rytka staggered to her feet, Sutcliffe again struck her on the back of the head with a hammer a number of times before retrieving a knife from his vehicle and stabbing her several times through the heart and lungs. Her body was found three days later behind a stack of timber, placed under a sheet of asbestos, beneath the railway arches of the timber yard.[2]: 112 Sutcliffe said of Rytka while in police custody in 1981: "I had the urge to kill any woman. The urge inside me to kill girls was now practically uncontrollable."[48]

Vera Evelyn Millward, 40, was a prostitute and mother of seven who left her council flat in Hulme at 10:00 p.m. on 16 May 1978, telling her boyfriend that she was going out to buy cigarettes. Sutcliffe picked up Millward and drove her to the parking compound of the Manchester Royal Infirmary in Chorlton-on-Medlock. After she got out of his car, Sutcliffe attacked her with a hammer. She was also slashed across the stomach and stabbed repeatedly with a screwdriver through the same wound in her back. After she died, Sutcliffe dragged her body against a fence and stabbed her repeatedly with a knife.[50]

1979

[edit]On the evening of 2 March 1979, 22-year-old Irish student Ann Rooney was attacked from behind at Horsforth College in Horsforth. Rooney was struck three times on the head, probably with a hammer, according to Professor David Gee, who examined her at Leeds General Infirmary. Rooney's description of her attacker and his car closely matched that of Sutcliffe and his black Sunbeam Rapier, which had been flagged by police numerous times in red-light districts in both Leeds and Bradford. In 1992, Sutcliffe confessed to the attack on Rooney, as well as the 1975 attack on Tracy Browne. Barbara Mills, Queen's Counsel, who was the Director of Public Prosecutions, decided at the time that it wasn't in the public's interest to add any additional charges against Sutcliffe for the attacks on Browne and Rooney.[51][52][53]

At 11:55 p.m. on 4 April 1979, Sutcliffe killed Josephine Anne Whitaker, a 19-year-old clerk, on Savile Park Moor in Halifax, West Yorkshire, as she was walking home. Sutcliffe hit Whitaker from behind with his ball-peen hammer and hit her again as she lay on the ground. Sutcliffe then proceeded to stab her with a screwdriver twenty-one times in the chest and stomach and six times in the right leg before also thrusting the screwdriver into her vagina. Whitaker's skull was fractured from ear to ear.[54]

Despite forensic evidence, police efforts were diverted for several months following the receipt of a taped message purporting to be from the murderer, taunting Assistant Chief Constable George Oldfield of the West Yorkshire Police, who was leading the investigation. The tape contained a man's voice saying, "I'm Jack. I see you're having no luck catching me. I have the greatest respect for you, George, but Lord, you're no nearer catching me now than four years ago when I started."[55] Based on the recorded message, police began searching for a man with a Wearside accent, which linguists narrowed down to the Castletown area of Sunderland, Tyne and Wear. The hoaxer, dubbed "Wearside Jack", sent two letters to police and the Daily Mirror in March 1978 boasting of his crimes. The letters, signed "Jack the Ripper", claimed responsibility for the November 1975 murder of 26-year-old Joan Harrison in Preston.

The hoaxer case was re-opened in 2005, and DNA taken from envelopes was entered into the national database. The DNA matched that of John Samuel Humble, an unemployed alcoholic and longtime resident of the Ford Estate in Sunderland — a few miles from Castletown — whose DNA had been taken following a drunk and disorderly offence in 2001. On 20 October 2005, Humble was charged with attempting to pervert the course of justice for sending the hoax letters and tape. He was remanded in custody and on 21 March 2006 was convicted and sentenced to eight years in prison.[56] Humble died on 30 July 2019, aged 63.[57]

At approximately 1:00 a.m. on 1 September, Sutcliffe murdered 20-year-old Barbara Janine Leach, a Bradford University social psychology student who had earlier left a pub.[58] She was attacked with a hammer after walking past him. He then dragged her to the backyard of 13 Back Ash Grove behind a low wall into an area where dustbins were kept before pulling up her shirt and bra to expose her breasts and unfastening her jeans and partially pulling them down. He then stabbed her with the same screwdriver that he had used to kill Josephine Whitaker. Sutcliffe then covered her body with an old piece of carpet and placed stones on top of it. The murder of another woman who was not a prostitute again alarmed the public and prompted an expensive publicity campaign emphasising the Wearside connection. Despite the false lead, Sutcliffe was interviewed on at least two other occasions in 1979. Despite matching several forensic clues and being on the list of 300 names in connection with the five-pound note, he was not strongly suspected.

1980

[edit]On 26 June 1980, Sutcliffe was stopped while driving, tested positive for drink driving and was arrested.[59] Whilst awaiting trial for this, due in mid-January 1981, he killed 47-year-old civil servant Marguerite Walls on the night of 20 August 1980. She left her office between 9:30 p.m. and 10:30 p.m. to walk to her home in Farsley. He incapacitated her with a hammer blow to the back of her head as he continued to strike her while yelling "filthy prostitute" beside a driveway.[60] In order to move her twenty yards from the place of the attack up the driveway and into a high-walled garden, he first tied a length of rope around her neck and tightened it. He choked her there, kneeling on her chest, and removed almost every piece of clothing from her once she was dead, leaving just her tights. He partially covered the body with grass and leaves before he left.

On 24 September 1980, a 34-year-old doctor from Singapore, Upadhya Bandara, was walking home from meeting friends when Sutcliffe followed her into an alley in Headingley, Leeds. He struck Bandara on the head, rendering her unconscious, then, when he was startled, dragged her along the street with a rope around her neck and fled.

Maureen Lea, 21, an art student at Leeds University, was attacked by Sutcliffe on 25 October 1980.[61] She was in a pub with friends in the Chapeltown neighbourhood of the city when she was attacked as she hurried down a dark street to catch the bus home. Lea was suffering from significant wounds when she awoke in the hospital, including a puncture hole to the back of her skull, a fractured skull, a fractured cheekbone, a broken jaw, and numerous scratches and bruises.

16-year-old Theresa Sykes, was attacked in Huddersfield on the night of 5 November 1980.[62] Sykes was going to a shop in Oakes, Huddersfield, when Sutcliffe hit her from behind. Sykes's boyfriend heard her screams and ran out, scaring Sutcliffe off. Sykes was recovering from brain surgery when Sutcliffe was arrested.

20-year-old Jacqueline Hill, a student at Leeds University, was murdered on the night of 17 November 1980.[60] She was returning home to her students' hall of residence in Headingley, Leeds when Sutcliffe delivered a blow to her head before removing her clothes and stabbing her repeatedly in the chest and once in the eye with a screwdriver.

On 25 November 1980, Trevor Birdsall, a friend of Sutcliffe's and the unwitting getaway driver in his first documented assault in 1969, reported him to the police as a suspect. In total, Sutcliffe had been questioned by the police on nine separate occasions in connection with the Ripper enquiry before his eventual arrest and conviction.[11]

Arrest

[edit]

On 2 January 1981, Sutcliffe was stopped by the police with 24-year-old prostitute Olivia Reivers (who received £3,000 from the Daily Express for her story) in the driveway of Light Trades House on Melbourne Avenue, Broomhill, Sheffield, South Yorkshire. A police check by probationary constable Robert Hydes revealed that Sutcliffe's car had false number plates; he was arrested and transferred to Dewsbury police station in West Yorkshire. At Dewsbury, Sutcliffe was questioned in relation to the Ripper case as he matched many of the known physical characteristics. The next day, Sergeant Robert Ring decided on a "hunch" to return to the scene of the arrest, and he discovered a knife, hammer, and rope that Sutcliffe had discarded behind an oil storage tank when he briefly slipped away after telling police he was "bursting for a pee". Sutcliffe hid a second knife in the toilet cistern at the police station when he was permitted to use the toilet. The police obtained a search warrant for his home in Heaton and brought his wife in for questioning.[63]

When Sutcliffe was stripped at Dewsbury police station he was wearing an inverted V-necked jumper under his trousers. The sleeves had been pulled over his legs, and the V-neck exposed his genital area. The fronts of the elbows were padded to protect his knees as, presumably, he knelt over his victims' corpses. The sexual implications of this outfit were considered obvious, but it was not known to the public until being published in 2003. After two days of intensive questioning, on the afternoon of 4 January 1981, Sutcliffe suddenly admitted that he was the Yorkshire Ripper. Over the next day, he calmly described his many attacks. Several weeks later he claimed God had told him to murder the women. "The women I killed were filth," he told police. "Bastard prostitutes who were littering the streets. I was just cleaning up the place a bit."[48] Sutcliffe displayed regret only when talking of his youngest murder victim, Jayne MacDonald, and showed emotion when questioned about the killing of Joan Harrison, which he vehemently denied having carried out. Harrison's murder had been linked to the Ripper killings by the "Wearside Jack" claim, but in 2011, DNA evidence revealed the crime had actually been committed by convicted sex offender Christopher Smith, who had died in 2008.[64]

Trial and conviction

[edit]Sutcliffe was charged on 5 January 1981. At his trial that May, he pleaded not guilty to thirteen charges of murder, but guilty to manslaughter on the grounds of diminished responsibility. The basis of his defence was that he claimed to be the tool of God's will. Sutcliffe said he had heard voices that ordered him to kill prostitutes while working as a gravedigger, which he claimed originated from the headstone of a Polish man, Bronisław Zapolski, and that the voices were that of God.[65][66]

Sutcliffe pleaded guilty to seven charges of attempted murder. The prosecution intended to accept his plea after four psychiatrists diagnosed him with paranoid schizophrenia, but the trial judge, Justice Sir Leslie Boreham, demanded an unusually detailed explanation of the prosecution's reasoning. After a two-hour representation by the Attorney-General, Sir Michael Havers, a ninety-minute lunch break, and another forty minutes of legal discussion, the judge rejected the diminished responsibility plea and the expert testimonies of the psychiatrists, insisting that the case should be dealt with by a jury. The trial proper was set to commence on 5 May 1981.[67]

The trial lasted two weeks, and despite the efforts of his counsel, James Chadwin QC, Sutcliffe was found guilty of murder on all counts and was sentenced to twenty concurrent sentences of life imprisonment.[68] The jury rejected the evidence of four psychiatrists who gave testimony that Sutcliffe had paranoid schizophrenia, possibly influenced by the evidence of a prison officer who heard him say to his wife that if he convinced people he was mad, he might get ten years in a "loony bin".[43]: 188

Justice Boreham stated that Sutcliffe was beyond redemption and hoped he would never leave prison. He recommended a minimum term of thirty years to be served before parole could be considered, meaning Sutcliffe would have been unlikely to be freed until at least 2011. On 16 July 2010, the High Court issued Sutcliffe with a whole life tariff, meaning he was never to be released.[69] After his trial, Sutcliffe admitted to two other attacks although he was not prosecuted for the offences.

Criticism of authorities

[edit]West Yorkshire Police

[edit]West Yorkshire Police were criticised for being inadequately prepared for an investigation on this scale. It was one of the largest investigations by a British police force[70] and predated the use of computers. Information on suspects was stored on handwritten index cards. Aside from difficulties in storing and accessing the paperwork, it was difficult for officers to overcome the information overload of such a large manual system.

Sutcliffe was interviewed nine times,[71] but all information the police had about the case was stored in paper form, making cross-referencing difficult, compounded by television appeals for information, which generated thousands more documents. The 1982 Byford Report into the investigation concluded: "The ineffectiveness of the major incident room was a serious handicap to the Ripper investigation. While it should have been the effective nerve centre of the whole police operation, the backlog of unprocessed information resulted in the failure to connect vital pieces of related information. This serious fault in the central index system allowed Peter Sutcliffe to continually slip through the net".[72]

The choice by Chief Constable Ronald Gregory of Oldfield to lead the inquiry was criticised by Byford: "The temptation to appoint a 'senior man' on age or service grounds should be resisted. What is needed is an officer of sound professional competence who will inspire confidence and loyalty".[73] He found Oldfield's focus on the hoax tape wanting,[74]: 86–87 [75] and that Oldfield had ignored advice from survivors of Sutcliffe's attacks, from several eminent specialists, from the FBI in the United States, and from dialect analysts[76] Stanley Ellis and Jack Windsor Lewis,[74]: 88 that "Wearside Jack" was a hoaxer.[e] Indeed, the investigation had used the hoax tape as a point of elimination, rather than as a line of enquiry, allowing Sutcliffe to avoid scrutiny as he did not fit the profile of the sender of the tape or letters. The "Wearside Jack" hoaxer was given unusual credibility when analysis of saliva on the envelopes he sent showed he had the same blood group as that which Sutcliffe had left at crime scenes, a type shared by only 6% of the population.[56] Humble, the hoaxer, appeared to know details of the murders that supposedly had not been released to the press, but which in fact he had acquired from his local newspaper, and from pub gossip.[78]

In response to the police reaction to the murders, the Leeds Revolutionary Feminist Group organised a number of 'Reclaim the Night' marches. The group and other feminists had criticised the police for victim-blaming, especially for the suggestion that women should remain indoors at night. Eleven marches in various towns across the United Kingdom took place on the night of 12 November 1977, making the points that women should be able to walk anywhere without restriction, and that they should not be blamed for men's violence.[74]: 83

In 1988, the mother of Sutcliffe's last victim, Jacqueline Hill, during an action for damages on behalf of her daughter's estate, argued in the case Hill v Chief Constable of West Yorkshire in the High Court that the police had failed to use reasonable care in apprehending Sutcliffe. The House of Lords held that the Chief Constable of West Yorkshire did not owe a duty of care to the victim due to the lack of proximity and therefore failed on the second limb of the Caparo test.[79] After Sutcliffe's death in November 2020, West Yorkshire Police issued an apology for the "language, tone, and terminology" used by the force at the time of the original investigation, nine months after a victim's son wrote on behalf of several of the victims' families.[80]

Attitude towards prostitutes

[edit]The attitude in the West Yorkshire Police at the time was one of misogyny and sexist attitudes, according to multiple sources.[81][43][82] Jim Hobson, a senior West Yorkshire detective, told a press conference in October 1979 the perpetrator:

...has made it clear that he hates prostitutes. Many people do. We, as a police force, will continue to arrest prostitutes. But the Ripper is now killing innocent girls. That indicates your mental state and that you are in urgent need of medical attention. You have made your point. Give yourself up before another innocent woman dies.[43]

Joan Smith wrote in Misogynies, that "even Sutcliffe, at his trial, did not go quite this far; he did at least claim he was demented at the time".[43] At Sutcliffe's trial in 1981, Attorney-General Sir Michael Havers, QC said of Sutcliffe's victims in his opening statement: "Some were prostitutes, but perhaps the saddest part of the case is that some were not. The last six attacks were on totally respectable women".[6] This drew condemnation from the English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP), who protested outside the Old Bailey.[83] Nina Lopez, who was one of the ECP protestors in 1981, told The Independent forty years later, Havers' comments were "an indictment of the whole way in which the police and the establishment were dealing with the Yorkshire Ripper case".[80]

Byford report

[edit]The Inspector of Constabulary Lawrence Byford's 1981 report of an official inquiry into the Ripper case[72] was not released by the Home Office until 1 June 2006. The sections "Description of suspects, photofits and other assaults" and parts of the section on Sutcliffe's "immediate associates" were not disclosed by the Home Office.[84] The Byford Report's major findings were contained in a summary published by the Home Secretary, William Whitelaw, disclosing for the first time precise details of the bungled police investigation. Byford described delays in following up vital tip-offs from Trevor Birdsall, who on 25 November 1980, sent an anonymous letter to police, the text of which ran as follows:

I have good reason to now [sic] the man you are looking for in the Ripper case. This man as [sic] dealings with prostitutes and always had a thing about them ... His name and address is (sic) Peter Sutcliffe, 5 Garden Lane, Heaton, Bradford Clarkes Trans. Shipley.[72]

Birdsall's letter was marked "Priority No. 1". An index card was created on the basis of the letter and a policewoman found Sutcliffe already had three existing index cards in the records. But "for some inexplicable reason", said the Byford Report, the papers remained in a filing tray in the incident room until Sutcliffe's arrest on 2 January 1981, several weeks later.[72] Birdsall visited Bradford police station the day after sending the letter to repeat his suspicion about Sutcliffe. He stated that he was with Sutcliffe when he got out of a car to pursue a woman with whom he had had an argument at a bar in Halifax on 15 August 1975 — the date and place of the Olive Smelt attack. A report compiled on the visit was lost, despite a "comprehensive search" that took place after Sutcliffe's arrest, according to the Byford Report.[72] Byford said:

The failure to take advantage of Birdsall's anonymous letter and his visit to the police station was yet again a stark illustration of the progressive decline in the overall efficiency of the major incident room. It resulted in Sutcliffe being at liberty for more than a month when he might conceivably have been in custody. Thankfully, there is no reason to think he committed any further murderous assaults within that period.[72]

Possible victims

[edit]Byford Report

[edit]Amongst other things, the Byford Report asserted that there was a high likelihood of Sutcliffe having claimed more victims both during and before his known killing spree. Police identified a number of attacks that matched Sutcliffe's modus operandi and tried to question the killer, but he was never charged with other crimes. Referring to the period between 1969, when Sutcliffe first came to the attention of police, and 1975, the year of his first documented murder, the report states, "There is a curious and unexplained lull in Sutcliffe's criminal activities," and "it is my firm conclusion that between 1969 and 1980 Sutcliffe was probably responsible for many attacks on unaccompanied women, which he has not yet admitted, not only in the West Yorkshire and Manchester areas, but also in other parts of the country."[85]

In 1969, Sutcliffe, described in the Byford Report as an "otherwise unremarkable young man," came to the notice of police on two occasions over incidents with prostitutes.[86] Later that year, in September 1969,[87] he was arrested in Bradford's red light area for being in possession of a hammer, an offensive weapon, but he was charged with "going equipped for stealing" as it was assumed he was a potential burglar.[86][72] The report said that it was clear Sutcliffe had on at least one occasion attacked a Bradford prostitute with a cosh.[86] Byford's report states:

We feel it is highly improbable that the crimes in respect of which Sutcliffe has been charged and convicted are the only ones attributable to him. This feeling is reinforced by examining the details of a number of assaults on women since 1969 which, in some ways, clearly fall into the established pattern of Sutcliffe's overall modus operandi. I hasten to add that I feel sure that the senior police officers in the areas concerned are also mindful of this possibility but, in order to ensure full account is taken of all the information available, I have arranged for an effective liaison to take place.[72]

Carol Wilkinson case

[edit]Only days after Sutcliffe's conviction in 1981, crime writer David Yallop asserted that Sutcliffe may have been responsible for the murder of 20-year-old Carol Wilkinson, who was randomly bludgeoned over the head with a stone in Bradford on 10 October 1977, nine days after his killing of Jean Jordan.[88][89] Wilkinson's murder had initially been considered as a possible "Ripper" killing, but this was quickly ruled out as she was not a prostitute.[90][89] Police eventually admitted in 1979 that the Ripper did not solely attack prostitutes, but by this time a local man, Anthony Steel, had already been convicted of Wilkinson's murder.[89] Yallop highlighted that Steel had always protested his innocence and been convicted on weak evidence.[91] He had confessed to the murder under intense questioning, having been told that he would be allowed to see a solicitor if he did so.[92] Even though his confession failed to include any details of the murder, and Ripper detective Jim Hobson testified at trial that he did not find the confession credible, Steel was narrowly convicted.[92]

Around the time of Wilkinson's murder it was widely reported that Professor David Gee, the Home Office pathologist who conducted all the post-mortem examinations on the Ripper victims, noted similarities between the Wilkinson murder and the killing of Ripper victim Yvonne Pearson three months later.[93] Like Wilkinson, Pearson was bludgeoned with a heavy stone and was not stabbed, and was initially ruled out as a "Ripper" victim.[89] Pearson's murder was re-classified as a Ripper killing in 1979 while Wilkinson's murder was not reviewed.[93][92] Sutcliffe did not confess to Wilkinson's murder at his trial, and Steel was already serving time for the murder. During his imprisonment, Sutcliffe was noted to show "particular anxiety" at mentions of Wilkinson due to the possible unsoundness of Steel's conviction.[10]

Sutcliffe was known to have been acquainted with Wilkinson and to have argued violently with Wilkinson's stepfather over his advances towards her.[94] He was familiar with the council estate where she was murdered and regularly frequented the area. In February 1977, only months before the murder, he was reported to police for acting suspiciously on the street where Wilkinson lived.[95] Furthermore, earlier on the day of Wilkinson's murder, Sutcliffe had gone back to mutilate Jordan's body before returning to Bradford, showing he had already gone out to attack victims that day and would have been in Bradford to attack Wilkinson after he returned from mutilating Jordan.[89][96] The location where Wilkinson was killed was also very close to Sutcliffe's place of employment, where he would have clocked in for work that afternoon.[97]

In 2003, Steel's conviction was quashed after it was found that his low IQ and mental capabilities made him a vulnerable interviewee, discrediting his supposed "confession" and confirming Yallop's long-standing suspicions that he had been wrongfully convicted.[92] Yallop continued to put forth the theory that Sutcliffe was the real killer.[89] In 2015, former detective Chris Clark and investigative journalist Tim Tate published a book, Yorkshire Ripper: The Secret Murders,[98] which supported the theory that Sutcliffe had murdered Wilkinson, pointing out that her body had been posed and partially stripped in a manner similar to the Ripper's modus operandi.[99][92]

Keith Hellawell investigations

[edit]In 1982, West Yorkshire Police appointed detective Keith Hellawell to lead a secret investigation into possible additional victims of Sutcliffe.[100][101] A list was compiled of around sixty murders and attempted murders not just in Yorkshire but around the country that West Yorkshire Police and other forces thought could possibly be linked to Sutcliffe.[100] Detectives were able to eliminate him from forty of these cases with reference to his lorry driver's logs which showed which part of the country he was in when he was working,[102] leaving twenty-two unsolved crimes with hallmarks of a Sutcliffe attack which were investigated further.[100][103][101] Twelve of these occurred within West Yorkshire while the others took place in other parts of the country.[104] Hellawell had also listed the attacks on Tracey Browne in 1975 and Ann Rooney in 1979 as possible Sutcliffe attacks, and it was to Hellawell that Sutcliffe confessed to these crimes in 1992, confirming police suspicions that he was responsible for more attacks than those he confessed to.[100]

- On 22 April 1966, shortly after 11:30 a.m., Fred Craven, 66, was murdered with a blunt instrument in his betting office above an antique shop in Wellington Street, Bingley.[105] His wallet, which was believed to have contained £200 in cash, had been stolen by his murderer.[106] Sutcliffe's brother, Michael, aged 16, was held for questioning but was eventually released and was ruled out as having any involvement in the crime.[107] Sutcliffe, then aged 20, knew Craven, who lived at 23 Cornwall Road, and the Sutcliffe family home where Sutcliffe lived was less than one hundred yards away at 57 Cornwall Road.[107] Sutcliffe had also asked Craven's daughter to go out with him several times and had been turned down.[107]

- On 22 March 1967, taxi driver John Tomey, 27, picked up a passenger in Leeds who wanted to be driven to Bingley; near Bingley he stopped and the passenger in the back then assaulted him with a hammer, hitting him in the head. When he regained consciousness, Tomey was able to drive off and get help at a nearby cottage.[105] He had suffered a fractured skull with multiple lacerations as well as a fractured thumb. In 1981, several weeks after Sutcliffe had confessed to being the Yorkshire Ripper, Detective Sergeant Des O'Boyle questioned Tomey, and showed him photographs of different men, including one taken of Sutcliffe after his arrest for going equipped for theft in 1969, which Tomey picked out as his attacker.

- On 11 November 1974, while walking across a school playing field in Bradford between 7:30 and 8:00 p.m., Gloria Wood, 28, met a man who offered to carry her bags. He then used what appeared to be a claw hammer to hit her in the head. She sustained serious wounds, including a depressed skull fracture with a crescent-shaped wound that later required surgery for the removal of bone shards from her brain. She was discovered drenched in blood after the attack was stopped by several nearby youths.[100] While she could not provide a photofit of her attacker, she described him as 5 feet 8 inches (1.73 m) tall with black hair and a beard, which fitted Sutcliffe's description.[100]

- 18-year-old Debra Marie Schlesinger was stabbed through the heart as she walked down the garden path of her home in Hawksworth, Leeds after a night out with friends on 21 April 1977. After being stabbed, she was chased. She then collapsed and died in a doorway.[100][101] Witnesses recalled seeing a dark, bearded man near the scene, and there was no clear motive for her murder.[100] Although a hammer was not used, Sutcliffe also often used a knife to stab his victims.[100] Most notably, Sutcliffe's work record also showed that he was delivering to an engineering plant 100 yards from Schlesinger's home on the day she was killed.[100] The killing took place only two days before Sutcliffe's known killing of Patricia Atkinson in Bradford.[100] At the time, detectives did not believe her murder was a "Ripper" killing as she was not a prostitute.[100] However, by 2002, West Yorkshire Police publicly announced they were ready to bring charges against Sutcliffe for her murder although no further action was taken.[103][100]

- Yvonne Mysliwiec, a 21-year-old reporter,[100] was attacked from behind after crossing a footbridge at the Ilkley railway station on 11 October 1979 and suffered a severe head injury. The attack was interrupted by a rail passenger. Her attacker was described as being in his thirties, dark, swarthy, square faced, and with crinkly hair, which matches Sutcliffe's description.[100][107] After Sutcliffe's trial, the West Yorkshire police announced that he would be questioned about the attack.

Additional investigations

[edit]In 2017, West Yorkshire Police launched Operation Painthall to determine if Sutcliffe was guilty of unsolved crimes dating back to 1964. In December 2017, West Yorkshire Police, in response to a Freedom of Information request, neither confirmed nor denied that Operation Painthall existed.[108]

- After his conviction in 1981, South Yorkshire Police interviewed Sutcliffe on the murder of 29-year-old Doncaster prostitute Barbara Young, who had been hit over the head by a "tall, dark haired man" in an alleyway on the evening of 22 March 1977.[109][102] A post-mortem revealed that she had died from a massive haemorrhage caused by a fractured skull. However, several aspects of the attack did not fit Sutcliffe's modus operandi, particularly as she had been hit from the front and had been the victim of a robbery.[102]

- On 28 August 1979, 32-year-old prostitute Wendy Jenkins, was killed in Bristol; she had been stabbed and beaten to death and was found partially buried in a building site sandpit. Avon and Somerset Police liaised with West Yorkshire Police as to whether there were any potential links to the "Ripper" killing spree.[110] Ripper detective Jim Hobson visited the site of the murder in Bristol, but there were a number of differences from Sutcliffe's known modus operandi.[110] Jenkins' murder remains unsolved.[110]

- Links were investigated in 2016 between Sutcliffe and the unsolved murders of two Swedish prostitutes in 1980. 31-year-old Gertie Jensen was found on a Gothenburg building site on 12 August 1980. On 30 August 26-year-old Teresa Thörling was found dead in the entrance to a building in Malmö. She had severe head wounds. Bo Lundqvist, a police cold-case investigator, stated that the murders bore Sutcliffe's signature in terms of their "sexually charged brutality." Sutcliffe's name appeared on the manifest of a ferry between Malmö and Dragor across the Oresund Strait a day before the second murder.[111] West Yorkshire Police later stated that it was "absolutely certain" that he had never been in Sweden.[112]

Yorkshire Ripper: The Secret Murders

[edit]In 2015, authors Chris Clark and Tim Tate published a book claiming links between Sutcliffe and unsolved murders, titled Yorkshire Ripper: The Secret Murders,[98] It alleged that between 1966 and 1980, Sutcliffe was responsible for at least twenty-two more murders than he was convicted of.[98] The book was later adapted into a two-part ITV documentary series of the same name, which featured both Clark and Tate.[92]

- Mary Judge, a 43-year-old prostitute, was found naked and battered to death on waste ground near the Leeds Parish Church on 22 February 1968. She was last seen outside Regent Hotel in the city centre. Passengers on a train from Kingston upon Hull are believed to have seen some of the attack as it passed the church at Kirkgate, Leeds at 10:18 p.m. A small boy on the train, which passed within 50 yards of the murder scene, was the main witness. He saw a tall, slim man with long dark hair beating Mary to the ground.[113]

- 21-year-old Lucy Tinslop was attacked after leaving her birthday party at 11:30 p.m. at St Mary's Rest Garden in Bath Street, Nottingham on 4 August 1969.[113] She had been raped and strangled; her abdomen had been ripped open and her vagina had been stabbed over twenty times which was consistent with Sutcliffe's modus operandi.

- 29-year-old Gloria Booth was found strangled and partially nude in Stonefield Park in Ruislip, West London, on 13 June 1971.[114][115] Police believe she was attacked as she walked home from work.[116] Sutcliffe was in the area at the time as his girlfriend was living in Alperton.[117]

- Judith Roberts, 14, was murdered on 7 June 1972, after leaving home to ride her bike in Wigginton, Staffordshire. She was found partially hidden beneath hedge clippings and plastic fertiliser bags face down later that day after going missing in a field north of Tamworth, Staffordshire; she had nineteen head wounds and had been battered to death.[118] 17-year-old Andrew Evans was wrongfully convicted and served 25 years in jail after confessing to the murder but had his conviction quashed in 1997.[119][120] On the evening of Roberts's death, Sutcliffe was driving to visit his fiancée, Sonia, at a hospital in Bexleyheath.[98] He would then have had to return to Bingley, West Yorkshire, where he worked nightshifts, which would have taken Sutcliffe within a short distance of the crime scene, Comberford Lane.[121][122] Sutcliffe also drove a grey Ford Escort, which is identical to a vehicle that four eyewitnesses observed trailing Judith as she made her way to local shops at the time of her disappearance.[118]

- 32-year-old legal secretary Wendy Sewell was attacked in Bakewell Cemetery at lunchtime on 12 September 1973.[123] She was beaten around the head seven times with the handle of a pickaxe, which had caused severe head injuries and fractures to her skull.[124] She had also been sexually assaulted. Clark and Tate claimed to have unearthed a pathology report which allegedly indicated that the originally convicted Stephen Downing could not have committed the crime.[125] The Home Office responded by stating that it would send any new evidence to the police.[125] Derbyshire Constabulary dismissed the theory, noting a re-investigation in 2002 had found only that Downing could not be ruled out of the investigation and responded by stating that there was no evidence linking Sutcliffe to the crime.[125]

- 24-year-old prostitute Rosina Hilliard was found on 22 February 1974, at a building site near Humberstone Road, Leicester. She had been hit by a car and suffered extensive head injuries and fractures to her spine and collar bone.[126][127] A post-mortem examination confirmed someone had also attempted to strangle her. Records show Sutcliffe was delivering goods to and from the area at the time.[128]

- One murder that was linked to Sutcliffe in the book, 25-year-old trainee teacher Alison Morris in Ramsey, Essex, on 1 September 1979, took place only six and a half hours before his known killing of Barbara Leach in Bradford, over 200 mi (320 km) away.[102] Morris was stabbed multiple times as she walked down a footpath along the Stour Brook, 250 yards from her home in Wrabness Road.[129] Authors Clark and Tate claimed that Sutcliffe could have been in Essex and still had enough time to drive back to Bradford to kill Leach later.[130] Morris's case remains unsolved.[131]

- Sally Shepherd, 24, was making her way home to Friary Road late at night after getting off a bus in Peckham, South London, on 1 December 1979 when she was clubbed unconscious, sexually assaulted, and beaten to death.[132] Her killer then dragged her body through a wire fence and left her at the back of Peckham Police Station in Staffordshire Street. Sally's murder and Sutcliffe's killing of Yvonne Pearson in January 1978 bore many similarities.[133] Sutcliffe's wife, Sonia, also did a teacher training course in nearby Deptford at the time, and Sutcliffe used to frequently visit her.[134]

Incarceration

[edit]Prison and Broadmoor Hospital

[edit]Following his conviction and incarceration, Sutcliffe chose to use the name Coonan, his mother's maiden name.[135] He began his sentence at HM Prison Parkhurst on 22 May 1981. Despite being found sane at his trial, Sutcliffe was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. Attempts to send him to a secure psychiatric unit were blocked. While at Parkhurst he was seriously assaulted by James Costello, a 35-year-old career criminal with several convictions for violence; on 10 January 1983, he followed Sutcliffe into a recess of F2, the hospital wing at Parkhurst, and plunged a broken coffee jar twice into the left side of Sutcliffe's face, creating four wounds requiring thirty stitches. In March 1984, Sutcliffe was sent to Broadmoor Hospital, under Section 47 of the Mental Health Act 1983.[136]

Sutcliffe's wife obtained a separation around 1989 and a divorce in July 1994.[137] On 23 February 1996, he was attacked in his room in Broadmoor's Henley Ward; Paul Wilson, a convicted robber, asked to borrow a videotape before attempting to strangle Sutcliffe with the cable from a pair of stereo headphones. After an attack with a pen by fellow inmate Ian Kay on 10 March 1997, Sutcliffe lost the vision in his left eye, and his right eye was severely damaged.[138] Kay admitted trying to kill Sutcliffe and was ordered to be detained in a secure mental hospital without limit of time.[139] In 2003, it was reported that Sutcliffe had developed diabetes.[140]

Sutcliffe's father died in 2004 and was cremated. On 17 January 2005, he was allowed to visit Arnside where the ashes had been scattered. The decision to allow the temporary release was initiated by David Blunkett and ratified by Charles Clarke when he became Home Secretary. Sutcliffe was accompanied by four members of the hospital staff. The visit led to front-page tabloid headlines.[141] On 22 December 2007, a fourth attack on Sutcliffe was made by fellow inmate Patrick Sureda, who lunged at him with a metal cutlery knife while shouting, "You fucking raping, murdering bastard, I'll blind your fucking other one!" Sutcliffe flung himself backwards and the blade missed his right eye, stabbing him in the cheek.[142]

On 17 February 2009, it was reported[143] that Sutcliffe was "fit to leave Broadmoor". On 23 March 2010, the Secretary of State for Justice, Jack Straw, was questioned by Julie Kirkbride, Conservative MP for Bromsgrove, in the House of Commons seeking reassurance for a constituent, a victim of Sutcliffe, that he would remain in prison. Straw responded that whilst the matter of Sutcliffe's release was a parole board matter, "that all the evidence that I have seen on this case, and it's a great deal, suggests to me that there are no circumstances in which this man will be released".[144]

Appeal

[edit]An application by Sutcliffe for a minimum term to be set, offering the possibility of parole after that date if it were thought safe to release him, was heard by the High Court on 16 July 2010.[145] The court decided that Sutcliffe would never be released.[146][147] Mitting stated:

This was a campaign of murder which terrorised the population of a large part of Yorkshire for several years. The only explanation for it, on the jury's verdict, was anger, hatred and obsession. Apart from a terrorist outrage, it is difficult to conceive of circumstances in which one man could account for so many victims.[148]

Psychological reports describing Sutcliffe's mental state were taken into consideration, as was the severity of his crimes.[149] Sutcliffe spent the rest of his life in custody. On 4 August 2010, a spokeswoman for the Judicial Communications Office confirmed that Sutcliffe had initiated an appeal against the decision.[150] The hearing for Sutcliffe's appeal against the ruling began on 30 November 2010, at the Court of Appeal.[151] The appeal was rejected on 14 January 2011.[152] On 9 March 2011, the Court of Appeal rejected Sutcliffe's application for leave to appeal to the Supreme Court.[153] In December 2015, Sutcliffe was assessed as being "no longer mentally ill".[154] In August 2016, a medical tribunal ruled that he no longer required clinical treatment for his mental condition, and could be returned to prison. Sutcliffe was reported to have been transferred from Broadmoor to HM Prison Frankland in August 2016.[155][156]

Death

[edit]Sutcliffe died at University Hospital of North Durham, at the age of 74, on 13 November 2020, from diabetes-related complications, after having previously returned to HMP Frankland following treatment for a suspected heart attack at the same hospital two weeks prior. He had a number of underlying health problems, including obesity and diabetes.[26][157][27][158] A private funeral ceremony was held, and Sutcliffe's body was cremated.[159]

Media

[edit]The song "Night Shift" by English post-punk band Siouxsie and the Banshees on their 1981 album Juju is about Sutcliffe.[160]

On 6 April 1991, Sutcliffe's father, John, talked about his son on the television discussion programme After Dark.[161][162]

This Is Personal: The Hunt for the Yorkshire Ripper, a British television crime drama miniseries, first shown on ITV from 26 January to 2 February 2000, is a dramatisation of the real-life investigation into the murders, showing the effect that it had on the health and career of Assistant Chief Constable George Oldfield (Alun Armstrong). The series also starred Richard Ridings and James Laurenson as DSI Dick Holland and Chief Constable Ronald Gregory, respectively. Although broadcast over two weeks, two episodes were shown consecutively each week. The series was nominated for the British Academy Television Award for Best Drama Serial at the 2001 awards.[163]

In 2009, the three TV films Red Riding, also called The Yorkshire Ripper trilogy, depicted some of Sutcliffe's deeds. The third book (and second episodic television adaptation) in David Peace's Red Riding series is set against the backdrop of the Ripper investigation. In that episode, Sutcliffe is played by Joseph Mawle. The 13 May 2013 episode of Crimes That Shook Britain focused on the case.[164]

On 26 August 2016, the police investigation was the subject of BBC Radio 4's The Reunion. Sue MacGregor discussed the investigation with John Domaille, who subsequently served as assistant chief constable in the West Yorkshire Police; Andy Laptew, a young detective who conducted interviews with Sutcliffe; Elaine Benson, a detective who was part of the investigative team; David Zackrisson, who worked on the false leads, the "Wearside Jack" tape and the Sunderland letters; and Christa Ackroyd, a local journalist.[165]

A three-part series of one-hour episodes, The Yorkshire Ripper Files: A Very British Crime Story, by filmmaker Liza Williams aired on BBC Four in March 2019. This included interviews with some of the victims, their families, police and journalists who covered the case. In the series she questions whether the attitude towards women on the part of both the police and society prevented Sutcliffe from being caught sooner.[166] On 31 July 2020, the series won the BAFTA prize for Specialist Factual TV programming.[167]

A play written by Olivia Hirst and David Byrne, The Incident Room, premiered at Pleasance as part of the 2019 Edinburgh Festival Fringe. The play focuses on the police force hunting Sutcliffe. The play was produced by New Diorama.[168]

In December 2020, Netflix released a four-part documentary entitled The Ripper, which recounts the police investigation into the murders with interviews from living victims, family members of victims and police officers involved in the investigation.[169]

In November 2021, American heavy metal band Slipknot released a song titled "The Chapeltown Rag", which is inspired by media reporting on the murders.[170]

In February 2022, Channel 5 released a 60-minute documentary entitled The Ripper Speaks: The Lost Tapes, which recounts interviews, and Sutcliffe speaking about life in prison and in Broadmoor Hospital, as well as crimes he had committed but that had not been seen or treated as "a Ripper killing".[171]

In 2023, the ITV1 drama The Long Shadow focused on Sutcliffe's crimes.[172][173]

See also

[edit]- Gordon Cummins – Blackout Ripper

- Anthony Hardy – Camden Ripper

- Steve Wright – perpetrator of the Ipswich serial murders

- Alun Kyte – Midlands Ripper

- David Smith – also a murderer of sex workers

- List of prisoners with whole-life orders

- List of serial killers in the United Kingdom

- List of serial killers by number of victims

- Murder of Lisa Hession – another infamous Greater Manchester murder four years after the Ripper spree

- Chris Clark – author of Yorkshire Ripper: The Secret Murders, a 2015 book claiming links between Sutcliffe and unsolved murders

Notes

[edit]- ^ The neurosurgeon was Dr. A. Hadi Khalili at Leeds General Infirmary

- ^ The neurosurgeon was Dr. A. Hadi Khalili at Leeds General Infirmary

- ^ In December 2007, McCann's eldest daughter, Sonia, died by suicide, reportedly after years of anguish and depression over the circumstances surrounding her mother's death, and the subsequent consequences to her and her siblings.[37]

- ^ Jordan was born and raised in Motherwell; she had run away from home at age sixteen in early 1973. Shortly thereafter, a young chef named Alan Royle had observed her wandering aimlessly around Manchester Piccadilly station. Upon learning she had no money or friends in Manchester, he invited her to move into his Newall Green flat. Jordan agreed, and the two soon began a relationship.[2]: 92–93

- ^ George Oldfield and other senior individuals involved in the hunt for the Yorkshire Ripper had consulted senior FBI special agents John Douglas and Robert Ressler in an effort to construct a psychological profile of the Yorkshire Ripper in 1979. According to Ressler, after Oldfield played the tape, Ressler said to Oldfield: "You do realise, of course, that the man on the tape is not the killer, don't you?" and Oldfield chose to ignore this observation.[77]

References

[edit]- ^ "Murderers by height". murdermiletours.com. Serial killers.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cross, Roger (1981). The Yorkshire Ripper: The in-depth study of a mass killer and his methods. UK: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-586-05526-7.

- ^ Carter, Claire (13 January 2020). "How Yorkshire Ripper Peter Sutcliffe developed his murderous hatred of women". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ The Yorkshire Ripper files: A very British crime story (TV documentary). BBC TV.

- ^ "The Yorkshire Ripper files: Why Chapeltown in Leeds was the 'hunting ground' of Peter Sutcliffe". The Yorkshire Post. 27 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ a b Dowling, Tim (27 March 2019). "The Yorkshire Ripper files review – a stunningly mishandled manhunt". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ "Sir Lawrence Byford: Yorkshire Ripper report author dies". BBC News (obituary). 12 February 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ "Yorkshire Ripper Peter Sutcliffe 'was never mentally ill' claims detective who hunted him". The Daily Telegraph. 1 December 2015. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ "A Killer 's Mask". trutv.com. Archived from the original on 21 March 2009. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ a b Yallop 2014.

- ^ a b Ch 5, documentary "Born to Kill", broadcast 12.05 am 21 September 2022: a profile of the serial killer.

- ^ https://www.examinerlive.co.uk/news/west-yorkshire-news/yorkshire-ripper-peter-sutcliffes-brother-19265650

- ^ Sunday Mirror – 16 May 1999

- ^ a b c Thornton, Lucy; Dzinzi, Mellissa (12 November 2020). "Yorkshire Ripper Peter Sutcliffe's brother describes disturbing childhood growing up with notorious serial killer". Huddersfield Daily Examiner.

- ^ a b Keppel, Robert D.; Birnes, William J. (2003). The Psychology of Serial Killer Investigations: The grisly business unit. Academic Press. pp. 32. ISBN 9780124042605.

- ^ a b c Jones, Stephen (12 August 2016). "Who is the Yorkshire Ripper Peter Sutcliffe? History of notorious killer who brutally murdered 13 women". The Mirror. MGN Ltd. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ Burn 1993, p. 142.

- ^ Burke, Darren (3 January 2018). "How police caught Yorkshire Ripper Peter Sutcliffe in Sheffield 37 years ago this week". i. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ General Register Office; United Kingdom; Volume: 4; Page: 0531

- ^ Gordon Burn, Somebody's Husband, Somebody's Son, London: Faber, pp. 152–153.

- ^ "Peter Sutcliffe". www.killers.wadum.dk. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ Phillips, Caroline. "How I got Into The Mind Of The Ripper". Evening Standard. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ "Manchester's Vilest: The Yorkshire Ripper". Manchester's Finest. 6 August 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ Steel, Fiona. "Peter Sutcliffe – a killer's mask". Trutv.com. Archived from the original on 21 March 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ^ "Yorkshire Ripper Peter Sutcliffe victims".

- ^ a b Parmenter, Tom; Mercer, David. "Yorkshire Ripper serial killer Peter Sutcliffe dies". Sky News. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Yorkshire Ripper Peter Sutcliffe dies". BBC News. 13 November 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ Brannen, Keith (ed.). "Chart". Execulink.com/~kbrannen.

- ^ "Looking back: The Yorkshire Ripper investigation". The Telegraph and Argus. UK.

- ^ Burn, Chris (26 March 2019). "Restoring reputations of Yorkshire Ripper's victims after decades of victim-blaming". The Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ Yallop 2014, p. 13.

- ^ Steel, Fiona. "Peter Sutcliffe – A Double Life". TruTV.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ a b c Lee, Carol Ann (15 November 2020). "Women who survived Sutcliffe's attacks also had to survive institutional sexism". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ Smith, Joan (30 May 2017). "The Yorkshire Ripper was not a 'prostitute killer' – now his forgotten victims need justice". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ Yorkshire Ripper victim Tracy Browne to tell of her ordeal, Bradford Telegraph and Argus.

- ^ WILMA McCANN, Execulink.

- ^ Stratton, Allegra (27 December 2007). "Daughter of Ripper victim kills herself". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ Macfarlane, Jenna (13 November 2020). "Yorkshire Ripper: Who were serial killer Peter Sutcliffe's victims? When did he get caught? And how did he die?". The Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Finnegan, Stephanie (13 November 2020). "Son of Yorkshire Ripper victim Emily Jackson says 'thank f*** for that' after killer's death". Leeds-Live.co.uk.

- ^ Irene Richardson, Execulink.

- ^ Patricia Atkinson, Execulink.

- ^ "Remembering each of the 13 victims of the Yorkshire Ripper and who they were". www.yorkshireeveningpost.co.uk. February 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Joan (1993) [1989]. Misogynies. London: Faber & Faber. p. 175.

- ^ Burn, Gordon (2010) [1984]. Somebody's Husband, Somebody's Son: The Story of the Yorkshire Ripper. London: Faber & Faber. p. 221. ISBN 9780571265046.

- ^ "The Attacks and Murders: JAYNE MacDONALD". Execulink.com.

- ^ Saunders, Emmeline; Carter, Helen (13 November 2020). "How Coronation Street's Les Battersby actor became a Yorkshire Ripper suspect – Bruce Jones says the mix-up cost him his marriage". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ "The Yorkshire Ripper". Crimes That Shook Britain: Season 4, Episode 4. (6 October 2013).

- ^ a b c Bindel, Julie (15 November 2020). "Peter Sutcliffe murdered 13 women: I was nearly one of them". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 15 November 2020. (subscription required)

- ^ "The Attacks and Murders: Helen Rytka". Execulink.com.

- ^ "The Attacks and Murders: VERA MILLWARD". Execulink.com.

- ^ Hicks, Tim (13 April 2018). "Peter Sutcliffe or "The Harrogate Ripper"?". North Yorks Enquirer. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ "The Attacks and Murders: Ann Rooney". Execulink.com.

- ^ Jagger, David (14 November 2020). "Looking back at the Yorkshire Ripper investigation". Telegraph & Argus. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ "The Attacks and Murders: JOSEPHINE WHITAKER". Execulink.com.

- ^ K. Brannen. "Jack tape - cassette recording". Execulink.com. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ a b Herbert, Ian (21 March 2006). "Wearside Jack: I deserve to go to jail for 'evil' Ripper hoax". The Independent. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ "Yorkshire Ripper hoaxer Wearside Jack dies". BBC News. 20 August 2019.

- ^ "The Attacks and Murders: BARBARA LEACH". Execulink.com.

- ^ Manchester Evening News – 23 May 1981 – Page 4

- ^ a b "The Attacks and Murders: MARGUERITE WALLS". Execulink.com.

- ^ Cocozza, Paula (5 December 2017). "'I've turned the tables on Peter Sutcliffe': artist Mo Lea on why she finally drew her attacker". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "THE ATTACKS AND MURDERS – THERESA SYKES". www.execulink.com. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Summers, Chris. "Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper". Crime Case Closed. BBC. Archived from the original on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ^ "DNA helps police "solve" 1975 Joan Harrison murder". BBC News. 9 February 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ "MP's Ripper prison demand". BBC News. 9 March 2003.

- ^ "Yorkshire Ripper, Peter Sutcliffe's weight-gain strategy in latest bid for freedom". New Criminologist. 25 May 2005. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012.

- ^ Radford, Jill (1992). Femicide : the politics of woman killing. New York Toronto New York: Twayne Maxwell, Macmillan Canada, Maxwell Macmillan International. ISBN 0805790284.

- ^ "1981: Yorkshire Ripper jailed for life". On This Day, 22 May 1981. BBC.

- ^ "Yorkshire Ripper: Tribunal rules Peter Sutcliffe can be sent to mainstream prison". The Guardian. 12 August 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ Ganzoni, John (19 January 1982). The Yorkshire Ripper Case. House of Lords Hansard (Report). Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ "One girl's life in the Ripper years". BBC News. 2 November 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Byford, Lawrence, Sir (December 1981). Report into the Police Handling of the Yorkshire Ripper Case (Report). London: Home Office.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (multiple files) - ^ Tendler, Stewart (2 June 2006). "Six more attacks that the Ripper won't admit". The Times. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ a b c Serial Murderers. Index. 1995. ISBN 1-85435-834-0.

- ^ "Story of Yorkshire Ripper hoaxer "Wearside Jack" to be made into movie". The Guardian. 15 June 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ "The Yorkshire Ripper Hoax Tape".

- ^ Ressler, Robert K.; Shachtman, Tom (1993). Whoever Fights Monsters. Pocket Books. pp. 260–261. ISBN 0-671-71561-5.

- ^ Marriott, Trevor (2007). Jack the Ripper: The 21st century investigation. Kings Road Publishing. p. 204. ISBN 9781843582427.

- ^ Judgments – Brooks (FC) (Respondent) versus Commissioner of Police for the Metropolis (Appellant) and others (Report). House of Lords Publications. 21 April 2005.

- ^ a b Oppenheim, Maya (13 November 2020). "Families of Yorkshire Ripper victims receive police apology for language used during investigation". The Independent. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ Pidd, Helen; Topping, Alexandra (13 November 2020). "'It was toxic': How sexism threw police off the trail of the Yorkshire Ripper". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ Bindel, Julie (2017). The Pimping of Prostitution: Abolishing the sex work myth. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p. ix. ISBN 9781349959471.

- ^ "Remembering the Ripper trial". Law Gazette.

- ^ "Mistakes that left Ripper on the loose". Yorkshire Post. 2 June 2006. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ Evans, Rob; Campbell, Duncan (2 June 2006). "Ripper guilty of additional crimes, says secret report". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ a b c "Ripper may have attacked more". Sydney Morning Herald. Reuters. 3 June 2006. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ Norfolk, Andrew (2 March 2010). "Peter Sutcliffe, the bullied mummy's boy who gave millions nightmares". The Times. London. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ "Ripper tape hoaxer is also a killer, claims new book". Belfast Telegraph. 25 May 1981.

- ^ a b c d e f "BBC - Inside Out - Yorkshire & Lincolnshire - Ripper mystery". BBC Inside Out. BBC. 27 July 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ Clark & Tate 2015, p. 231.

- ^ "Ripper hoaxer 'double killer'". Newcastle Journal. 25 May 1981. p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f "Yorkshire Ripper: The Secret Murders. Episode 1". ITV Hub. ITV. 23 February 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ a b Williams, John (28 March 1978). "'Ripper' May Have an Imitator". The Telegraph.

- ^ Clark & Tate 2015, pp. 231–232.

- ^ Clark & Tate 2015, p. 232.

- ^ Clark & Tate 2015, p. 229.

- ^ Clark & Tate 2015, pp. 230.

- ^ a b c d Clark & Tate 2015.

- ^ Clark & Tate 2015, pp. 230–231.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Glyn Middleton (director and producer) (10 December 1996). Silent Victims: The Untold Story of the Yorkshire Ripper (1996). Yorkshire Television.

- ^ a b c Goodchild, Sophie (24 November 1996). "Yorkshire Ripper 'has admitted more attacks'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d Brannen, K. "Other Yorkshire Ripper Victims?". Yorkshire Ripper website. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ a b Clark & Tate 2015, p. 351.

- ^ Clark & Tate 2015, pp. 335–336.

- ^ a b NEW CLAIMS OF YORKSHIRE RIPPER CRIMES, BBC.

- ^ Meneaud, Marc (9 March 2010). "Bingley bookmaker's daughter fears Peter Sutcliffe killed her dad". Telegraph & Argus. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d Heenan Bhatti (director) (4 March 2021). The Yorkshire Ripper's New Victims. My5: Channel 5. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Operation Painthall". whatdotheyknow.com. 21 December 2017.

- ^ "Police to Quiz Ripper". The Telegraph. 27 May 1981.

- ^ a b c Churchill, Laura (16 April 2017). "The Bristol prostitute murdered as the Yorkshire Ripper hunted red light districts". Bristol Post. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "The Yorkshire Ripper and the unsolved Swedish murders". BBC News. 12 January 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ Smith, Joan (30 May 2017). "The Yorkshire Ripper was not a 'prostitute killer' – now his forgotten victims need justice". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 13 January 2018.