Sergei Prokofiev set to work on his Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 16, in 1912 and completed it the next year. However, that version of the concerto is lost; the score was destroyed in a fire following the Russian Revolution. Prokofiev reconstructed the work in 1923, two years after finishing his Piano Concerto No. 3, and declared it to be "so completely rewritten that it might almost be considered [Piano Concerto] No. 4." Indeed, its orchestration has features that clearly postdate the 1921 concerto. Performing as soloist, Prokofiev premiered this "No. 2" in Paris on 8 May 1924 with Serge Koussevitzky conducting. It is dedicated to the memory of Maximilian Schmidthof, a friend of Prokofiev's at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, who had committed suicide in April 1913[1] after having written a farewell letter to Prokofiev.[2]

Movements and scoring

[edit]The work is scored for piano solo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, snare drum, cymbals, tambourine and strings. It consists of four movements lasting some twenty-nine to thirty-seven minutes.

- Andantino—Allegretto (10–12 minutes)

- Scherzo: Vivace (2–3 minutes)

- Intermezzo: Allegro moderato (6–8 minutes)

- Finale: Allegro tempestoso (10–11 minutes)

Premiere and reception

[edit]Prokofiev premiered the work originally on September 5, 1913 (August 23 on the calendar used in Russia at that time), performing the solo piano part, at Pavlovsk.[3] Most of the audience reacted intensely. The concerto's wild temperament left a positive impression on some of the listeners, whereas others were opposed to the jarring and modernistic sound ("To hell with this futurist music!" "What is he doing, making fun of us?" "The cats on the roof make better music!").[4][5]

When the original orchestral score was destroyed in a fire following the Russian Revolution,[6] Prokofiev reconstructed and considerably revised the concerto in 1923; in the process, he made the concerto, in his own words, "less foursquare" and "slightly more complex in its contrapuntal fabric."[6] The finished result, Prokofiev felt, was "so completely rewritten that it might almost be considered [Concerto] No. 4."[1] (Piano Concerto No. 3 had premiered in 1921). He premiered this revised version of the concerto in Paris on May 8, 1924, with Serge Koussevitzky conducting.[1]

It remains one of the most technically formidable piano concertos in the standard repertoire. Prokofiev biographer David Nice noted in 2011, "A decade ago I’d have bet you there were only a dozen pianists in the world who could play Prokofiev’s Second Piano Concerto properly. Argerich wouldn’t touch it, Kissin delayed learning it, and even Prokofiev as virtuoso had got into a terrible mess trying to perform it with Ansermet and the BBC Symphony Orchestra in the 1930s, when it had gone out of his fingers."[7]

Analysis

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2010) |

The first and last movements are each around twelve minutes long and constitute some of the most dramatic music in all of Prokofiev's piano concertos. They both contain long and developed cadenzas with the first movement's cadenza alone taking up almost the entire last half of the movement.

Andantino—Allegretto

[edit]The first movement opens quietly with strings and clarinet playing a two-bar staccato theme which, Prokofiev biographer Daniel Jaffé suggests, "sounds almost like a ground bass passacaglia theme, that musical symbol of implacable fate".[8] The piano takes over, constructing over a left hand accompaniment of breathing undulation a G minor narrante theme which, in the words of Soviet biographer Israel Nestyev, "suggests a quiet, serious tale in the vein of a romantic legend".[9] This opening theme contains a second idea,[10] a rising scalic theme; as Robert Layton observes, when it is later taken up by unison strings as "a broad singing melody, one feels that the example of Rachmaninov has not gone altogether unheeded".[11]

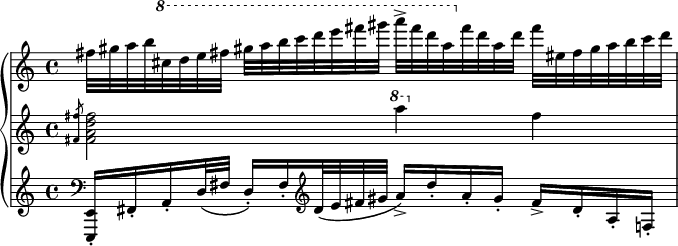

A brief forte, backed by the orchestra, leads to a third, expansive, walking theme performed again by the solo pianist; Layton notes that this "looks forward to its counterpart in the Third Piano Concerto: there is no mistaking its slightly flippant character".[11] The recapitulation section is in effect carried entirely by the soloist's notoriously taxing five-minute cadenza, one of the longer and more difficult cadenze in the classical piano repertoire, taking the listener all the way to the movement's climax. Noted in two staves, the piano plays a reprise of its own opening theme. A third staff, which requires the pianist to perform large jumps with both hands frequently, contains the motif from the earlier orchestral accompaniment.

The accumulated charge is eventually released in a premature climax (G minor), marked fff and colossale, which consists of oscillating triplet semiquaver runs across the upper four octaves of the piano, kept in rhythm by a leaping left-hand crotchet accompaniment. Prokofiev himself describes this as one of the hardest places in the concerto.[12]

The last bars before the absolute climax are marked tumultuoso and reach supreme discord as C sharp minor collides with D minor.

As both hands move apart, to embrace the piano fff in D minor, an accent on every note, the orchestra announces its return, strings and timpani swelling furiously from p to ff. The listener is exposed to the apocalyptic blare of several horns, trombones, trumpets and tuba, which, as Jaffé describes it, "balefully [play] the opening 'fate' theme fortissimo",[8] while piano, flutes and strings still shriek in unison up and down the higher ranges. Two cymbal crashes end the cataclysm in G minor.

A decrescendo brings the music back to an almost spooky piano in which the piano timidly puts forth the second narrante theme, echoes its last notes, repeats it pianissimo, ever fading. Pizzicato strings point several more times to the opening theme, the significance of which has now been revealed.

Scherzo: Vivace

[edit]The scherzo is of an exceptionally strict form considering the piano part. The right and left hand play a stubborn unison, almost 1500 semiquavers each, literally without a moment's pause: Robert Layton describes the soloist in this movement being like "some virtuoso footballer who retains the initiative while the opposing team (the orchestra) all charge after him".[11] At around ten notes a second and with hardly any variations in speed, this movement lasts circa two-and-a-half minutes and is an unusual concentration challenge to the pianist. It displays the motor line of the five "lines" (characters) Prokofiev describes in his own music. (Other such pieces include Toccata in D minor and the last movement of Piano Sonata No. 7.) One fleeting motif, to make a major appearance in the final movement, appears (fig. 39 in the score) in the cellos' part – "a chromatically inflected triplet plus quaver, played twice before tailing off".[8] Unlike the other three movements, it is mainly in D minor.

Intermezzo: Allegro moderato

[edit]Instead of a lyrical slow movement which might have been expected after a scherzo (cf Brahms's Second Piano Concerto), Prokofiev provides a fast-paced, menacing Intermezzo.[11] Layton characterises this movement as "in some ways the most highly characterized of all four movements, with its flashes of sardonic wit and forward-looking harmonies".[11]

The movement starts with a heavy-footed walking bass theme – directed to be played heavily (pesante) and fortissimo. The music has returned to G minor. Strings, bassoon, tuba, timpani and gran cassa (bass drum) march along with moody determination. Trombones sharply pronounce a D, followed by tuba and oboe in a sudden diminuendo. For several bars, the orchestra issues ever waning threats, at the same time making inexorably for the tonic, at which point the piano enters and the music immediately gains force. The march of the introduction continues as the piano modulates into new harmonic territory. There is one moment of respite from this "sarcastically grotesque procession" with the single appearance of "an introverted theme of numbed lyricism".[8] After a restatement of the earlier material, the music ventures into a new lyrical theme in D minor, marked pp and dolce, un poco scherzando. The piano and flutes gracefully glide up and down the upper octaves. Then, the piano repeats the theme by itself, humorous and secco, before being joined by the orchestra. The tension builds and the music ascends until it reaches a climax, when the opening theme returns with baleful trombones and crashing chords at the top of the piano. The woodwinds bring the intensity back down and the movement ends quietly with a final stroke of wit.

Finale: Allegro tempestoso

[edit]Five octaves above the intermezzo's end note, a fortissimo tirade pounces out of the sky, written in 4

4 but with a repeating pattern seven quavers long (accented as 4+3). After six bars it settles down in the vicinity of middle C. Running up to an acid semitonal acciaccatura in both hands, the piano goes over into a sprint of octave-chords and single notes, jumping manically up and down the keyboard twice a bar. An audible theme is picked out, and during a piano and staccato repetition of the theme, the strings and flutes rush up, bringing the music to the briefest of halts. A moment later the piano goes back to forte and the sprint sets off anew. It is repeated three more times in total before the piano performs a stormy gallop of triads (tempestoso), the hands flying apart more or less symmetrically, while the strings throw in a frantic accompaniment of regular staccato eighths. The piano puts a momentary end to its own fury with a barely feasible manoeuvre, both hands jumping up three or four octaves simultaneously and fortissimo in the time of a semiquaver. But by then the sprint has transformed into a "fearful pursuit with an obsessively repeated triplet motif [first heard fleetingly in the Scherzo movement] overshadowed by the baleful roars of tuba and trombones".[8] Only moments later, the orchestra has reached a halt and the piano, unaccompanied, plays soft but dissonant chords which, Jaffé suggests, are "reminiscent of the bell-like chords which open the final piece in Schoenberg's Six Little Piano Pieces, Op. 19" which were composed in homage to Mahler shortly after his death. (Jaffé points out that Prokofiev had introduced Schoenberg's music to Russia by playing the Op. 11 pieces, and suggests that Prokofiev may have known and been inspired by Schoenberg's Op. 19 to use a similar bell motif to commemorate Schmidthof.)[8]

The piano stands aside for eight bars while the strings, still mf, embark on a new episode. The soloist then plays a wistful theme in D minor similar in character to the first movement's piano opening theme, characterised by Jaffé as a "lullaby" while noting (as does Nestyev)[13] its affinity to Mussorgsky. The bassoons take up the wandering piano-theme, while the piano itself goes over into a pp semiquaver accompaniment. The music eventually winds down, with "a despondent-sounding version of the lullaby theme on bassoon abruptly cut off by a sharply articulated and very final sounding cadence from the orchestra".[8] But, as Jaffé notes, "The pianist won't let things rest... but hammers out the 'pursuit' theme", so initiating "not so much a cadenza... but a post-cadential meditation on the 'bell' chords".[8] The orchestra joins in after some time, reintroducing the piano's "lullaby" theme, while the soloist's part still flows across the octaves. The key regularly changes from A minor to C minor and back again, the music becomes ever broader and harder to play. Rhythm and tune then fall into an abrupt piano, no less threatening than the previous forte. Trundling chromaticism has the music roll up to a fortissimo, the orchestra still proclaiming the originally wistful piano-theme. This is the only place outside the andantino where the piano exceeds the older range of seven octaves, jumping two octaves up to B7 just one single time.

A long diminuendo of gliding piano rushes brings the volume to a minimum pp (Prokofiev does not once use a ppp in the concerto's piano part). Then a ferocious blast (ff) from the orchestra starts off the ferocious reprise.

Recordings

[edit]The first recording of the concerto was made in November 1953 and released the next year on Remington Records: R-199-182. The pianist was Jorge Bolet, the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra was led by Thor Johnson, and Laszlo Halasz and Don Gabor supervised. Bolet's performance set a standard by which several later recordings were judged: Shura Cherkassky and Herbert Menges (HMV mono); Nicole Henriot and Charles Munch (with a bad cut in the first movement; RCA stereo); and Malcolm Frager and René Leibowitz (also RCA stereo). Tedd Joselson, then 19 years old, launched his recording career with this work in a 1973 partnership with the Philadelphia Orchestra and conductor Eugene Ormandy (again on RCA).

List

[edit]| Year | Pianist | Orchestra | Conductor | Mvt 1 | Mvt 2 | Mvt 3 | Mvt 4 | Label | Catalog |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | Bolet | Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra | Johnson | 10:42 | 2:25 | 5:50 | 11:03 | Remington | R-199-182 |

| 1954 live | Scarpini | New York Philharmonic | Mitropoulos | 11:29 | 2:33 | 6:07 | 11:43 | Music & Arts | CD-1214 |

| 1955 | Cherkassky | Philharmonia Orchestra | Menges | 10:52 | 2:34 | 5:38 | 11:03 | HMV | ALP 1349 |

| 1957 | Henriot | Boston Symphony Orchestra *omits orchestra's exposition |

Munch | 9:31* | 2:35 | 5:39 | 11:50 | RCA | LM-2197 |

| 1958 live | Ashkenazy | New York Philharmonic | Bernstein | 11:51 | 2:32 | 5:59 | 10:36 | NYPO Special Editions | NYP 2003 |

| 1959 | Zak | USSR Radio Symphony Orchestra | Sanderling | 11:11 | 2:33 | 7:09 | 10:24 | Апрелевский Завод (Aprelevsky Zavod) | ГОСТ 5289-56 |

| 1960 | Frager | Paris Conservatoire Orchestra | Leibowitz | 10:44 | 2:44 | 6:06 | 10:55 | RCA | LSC-2465 |

| 1961 live | Ashkenazy | USSR State Symphony Orchestra | Rozhdestvensky | 11:31 | 2:40 | 6:42 | 10:36 | Brilliant Classics | 9098-30 |

| 1961 | Wührer | Südwestfunk Orchester Baden-Baden | Gielen | 13:00 | 3:01 | 7:48 | 13:10 | Vox | PL 12.100 |

| 1963 | Baloghová | Czech Philharmonic | Ančerl | 12:14 | 2:45 | 7:22 | 11:19 | Supraphon | SUA ST 50551 |

| 1965 | Browning | Boston S.O. | Leinsdorf | 10:49 | 2:36 | 6:51 | 11:03 | RCA | LSC-2897 |

| 1969 | Rösel | Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra | Bongartz | 11:17 | 2:29 | 7:04 | 10:44 | Edel | CCC 01072 |

| 1972 | Bolet | Nürnberger Symphoniker | Cox | 10:58 | 2:28 | 6:05 | 11:07 | Genesis | GCD-104 |

| 1972 | Tacchino | Orchestre de Radio Luxembourg | de Froment | 10:56 | 2:49 | 6:07 | 10:46 | Candide | CE 31075 |

| 1973 | Joselson | Philadelphia Orchestra | Ormandy | 12:08 | 2:30 | 7:07 | 12:25 | RCA | ARL1-0751 |

| 1974 | Béroff | Gewandhaus Orchestra | Masur | 10:19 | 2:33 | 5:46 | 10:43 | EMI Pathé Marconi | 2C-069-02764 |

| 1974 | Ashkenazy | London Symphony Orchestra | Previn | 12:08 | 2:36 | 6:22 | 11:26 | Decca | SXL 6767 |

| 1976 | Krainev | Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra | Kitaenko | 12:13 | 2:30 | 6:54 | 11:10 | Melodiya | С10-17139-40 |

| 1977 | Alexeev | Royal Philharmonic Orchestra | Temirkanov | 11:58 | 2:44 | 7:54 | 11:30 | EMI | ASD 3871 |

| 1978 live | El Bacha | Orchestre National de Belgique | Octors | 11:23 | 2:33 | 6:31 | 11:00 | Deutsche Grammophon | 2531 070 |

| 1983 | Postnikova | USSR Ministry of Culture Symphony Orchestra | Rozhdestvensky | 12:40 | 2:43 | 7:36 | 12:01 | Melodiya | С10-23893-006 |

| 1983 | Lapšanský | Slovak Philharmonic | Košler | 12:33 | 2:40 | 6:55 | 12:07 | Opus | 9110 1510 |

| 1984 live | Gutiérrez | Berlin Philharmonic | Tennstedt | 11:29 | 2:36 | 6:59 | 11:44 | Testament | SBT2 1450 |

| 1988 | Feltsman | London Symphony Orchestra | Tilson Thomas | 11:45 | 2:41 | 7:00 | 11:16 | CBS | MK 44818 |

| 1990 | Gutiérrez | Concertgebouw Orchestra | Järvi | 10:59 | 2:29 | 6:42 | 10:59 | Chandos | CHAN 8889 |

| 1991 | Paik | Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra | Wit | 12:40 | 2:24 | 6:36 | 11:46 | Naxos | 8.550565 |

| 1991 live | Cherkassky | London Philharmonic Orchestra | Nagano | 11:56 | 2:48 | 6:38 | 12:59 | BBC Legends | BBCL 4092-2 |

| 1991 live | Petrov | USSR Ministry of Culture Symphony Orchestra | Rozhdestvensky | 11:40 | 2:34 | 7:39 | 11:08 | Melodiya | RCID18529725 |

| 1992 | Krainev | Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra | Kitaenko | 11:30 | 2:33 | 6:42 | 10:56 | Teldec | 4509-99698-2 |

| 1993 | Bronfman | Israel Philharmonic Orchestra | Mehta | 11:04 | 2:28 | 6:20 | 10:50 | Sony | SK 58966 |

| 1995 live | Toradze | Kirov Orchestra | Gergiev | 13:23 | 2:20 | 7:34 | 12:59 | Philips | 462 048-2 |

| 1995 | Demidenko | London Philharmonic Orchestra | Lazarev | 12:28 | 2:39 | 8:35 | 11:48 | Hyperion | CDA 66858 |

| 1996 live | Takao | Sydney Symphony Orchestra | Tchivzhel | 11:47 | 2:25 | 6:40 | 11:49 | ABC Classics | 454 975-2 |

| 2001 | Marshev | South Jutland Symphony Orchestra | Willén | 14:01 | 2:33 | 7:36 | 13:11 | Danacord | DACOCD 585 |

| 2002 | Rodrigues | Saint Petersburg Philharmonic | Serov | 11:51 | 2:32 | 7:25 | 12:59 | Northern Flowers | NFPMA 09 019 |

| 2004 live | El Bacha | Orchestre Symphonique de la Monnaie | Ōno | 11:33 | 2:35 | 6:24 | 10:58 | Fuga Libera | FUG 505 |

| 2004 live | Hill | Sydney Symphony Orchestra | Fürst | 11:44 | 2:50 | 7:48 | 13:08 | ABC Classics | 476 433-1 |

| 2007 live | YUNDI | Berlin Philharmonic | Ozawa | 11:09 | 2:17 | 5:41 | 11:02 | Deutsche Grammophon | 477 659-3 |

| 2008 live | Kissin | Philharmonia Orchestra | Ashkenazy | 11:56 | 2:24 | 6:35 | 11:38 | EMI | 2-64536-2 |

| 2008 | Kempf | Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra | Litton | 12:09 | 2:29 | 5:56 | 11:30 | BIS | BIS-1820 SACD |

| 2009 | Vinnitskaya | Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin | Varga | 12:07 | 2:26 | 7:42 | 11:03 | Naïve | V-5238 |

| 2009 | Gavrilyuk | Sydney Symphony Orchestra | Ashkenazy | 12:23 | 2:42 | 5:58 | 11:46 | Triton | EXCL-00044 |

| 2010 live | Kozhukhin | Orchestre National de Belgique | Alsop | 12:37 | 2:40 | 7:35 | 12:59 | Off The Records | QEC 2010 |

| 2010 live | Bronfman | New York Philharmonic | Gilbert | 10:25 | 2:31 | 6:08 | 10:45 | Apple iTunes | n/a |

| 2013 live | Wang | Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra | Dudamel | 11:01 | 2:21 | 6:34 | 10:59 | Deutsche Grammophon | 479 130-4 |

| 2013 | Bavouzet | BBC Philharmonic | Noseda | 11:09 | 2:31 | 6:19 | 11:22 | Chandos | CHAN 10802 |

| 2014 | Gerstein | Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin | Gaffigan | 10:59 | 2:36 | 6:48 | 10:53 | Myrios | MYR 016 |

| 2014 | Shelest | Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra | Muus | 11:51 | 2:30 | 6:52 | 12:20 | Sorel | SOLR 006 |

| 2015 | Kholodenko | Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra | Harth-Bedoya | 12:10 | 2:39 | 6:42 | 11:55 | Harmonia Mundi | HMU 807631 |

| 2015 | Rana | Orchestra of Santa Cecilia | Pappano | 11:40 | 2:26 | 6:07 | 11:48 | Warner | 08256 46009 091 |

| 2016 live | Matsuev | Mariinsky Orchestra | Gergiev | 11:21 | 2:20 | 6:30 | 11:38 | Mariinsky | MAR 0599 |

| 2017 | Mustonen | Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra | Lintu | 11:58 | 2:59 | 7:04 | 12:10 | Ondine | ODE 12882 |

| 2018 | Zhang | Lahti Symphony Orchestra | Slobodeniouk | 11:24 | 2:31 | 6:33 | 11:33 | BIS | BIS-2381 SACD |

| 2020 | Trifonov | Mariinsky Orchestra | Gergiev | 11:52 | 2:31 | 6:55 | 11:12 | Deutsche Grammophon | 483 533-1 |

Recommendations

[edit]The Prokofiev Page, a website by Sugi Sorensen, recommended the recording by Gutiérrez with Järvi and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra;[14] this received more acclaim when reissued in 2009.[15][16] The recording by Yundi Li with Ozawa and the Berlin Philharmonic in 2007 is widely praised:[17] [18][19][20] The New York Times recommended and regarded it as year‘s most notable,[21] while it is listed in The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music 3 Stars.[22] More recently the Grammy-winning recording by Kissin, with Ashkenazy now conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra, has received praise, as has that by Wang and Dudamel.[23][24]

In 2016 Beatrice Rana's recording with the Orchestra of L'Accademia di Santa Cecilia di Roma conducted by Antonio Pappano, received Gramophone Magazine's Editor's Choice, and BBC Magazine's Record of the Month.

The concerto's scherzo provides the musical score for Swiss animator Georges Schwizgebel's animated short, Jeu.[25][26]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Steinberg, M. The Concerto: A Listener's Guide, pp. 344–347, Oxford (1998).

- ^ Naxos.com: online liner notes

- ^ Jaffé 2008, p. 35.

- ^ "Sergei Prokofiev Foundation".

- ^ "San Francisco Symphony Program Notes". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27.

- ^ a b Nice 2003, p. 94

- ^ Nice, David. "Review: Anna Vinnitskaya recording of Prokofiev Piano Concerto No. 2.", BBC Music Magazine, February 2011

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jaffé (Danacord)

- ^ Nestyev 1961, p. 73.

- ^ Matthew-Walker.

- ^ a b c d e Layton 1996, p. 206

- ^ Prokofiev, Sergey (1992). Soviet diary, 1927, and other writings. Oleg Prokofiev, Christopher Palmer. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 61. ISBN 1-55553-120-2. OCLC 25130975.

- ^ Nestyev 1961, p. 74.

- ^ Sorensen,Sugi; Choi, Lionel. "Piano Concerto No 2 in G minor, Op 16". The Prokofiev Page. Sugi Sorensen. Archived from the original on 30 November 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ Morrison, Bryce (September 2009). "Review". Gramophone. Retrieved 17 July 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Parry, Tim (August 2009). "Review". BBC Music Magazine. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Michael Cookson. "Yundi Li Prokofiev / Ravel Piano Concertos /Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor CD Review". MusicWeb International. Retrieved 2023-12-22.

- ^ "Prokofiev Piano Concerto No 2; Ravel Piano Concerto Power and brilliance, and enchantment too, from a marvellous young pianist". Gramophone. Retrieved 2023-12-22.

- ^ Colin Anderson (3 June 2008). "Yundi Li – Prokofiev & Ravel Piano Concertos/Seiji Ozawa". The Classical Source. Retrieved 2023-12-22.

- ^ Rolf Kyburz (8 Sep 2014). "Sergei Prokofiev Piano Concerto No.2 in G minor, op.16 Media Review / Comparison". Rolf’s Music Blog.

- ^ "Strings and Things: Classical's Best and Brightest". The New York Times. 30 Nov 2007.

- ^ March, Ivan; Greenfield, Edward; Layton, Robert. The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music 2010: The Key Classical Recordings on CD, DVD and SACD. Penguin Books. p. 575.

- ^ "Classical Net Review – Prokofieff/Rachmaninoff – Piano Concerto #2/Piano Concerto #3". Classical Net. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- ^ "Rachmaninov: Piano Concerto No. 3; Prokofiev: Piano Concerto No. 2 – Yuja Wang, Gustavo Dudamel – Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- ^ Townsend, Emru (August 24, 2006). "Jeu: Georges Schwizgebel's Game Without Frontiers". Frames per Second. Montreal. Archived from the original on December 18, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- ^ Schwizgebel, Georges (2006). "Jeu". National Film Board of Canada. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

References

[edit]- Jaffé, Daniel (2008). Sergey Prokofiev. London: Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-4774-0.

- Jaffé, Daniel. Booklet note to Prokofiev 5 Piano Concertos, recorded by Oleg Marshev with South Jutland Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Niklas Willén: Danacord DACOCD 584–585.

- Layton, Robert (1996). "Russia after 1917". In Robert Layton (ed.). A Guide to the Concerto. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-288008-X.

- Matthew-Walker, Robert. Booklet note to Prokofiev Piano Concerto No. 2, recorded by Nikolai Demidenko with London Philharmonic, conducted by Alexander Lazarev: Hyperion CDA 66858.

- Nestyev, Israel (1961). Prokofiev. Oxford University Press.

- Nice, David (2003). Prokofiev: From Russia to the West 1891–1935. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09914-2.

External links

[edit]- Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 16 (Prokofiev): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- The Prokofiev Page (including Catalog of Prokofiev works)

- Online version of Liner Notes from Recording on Naxos

- Video (32:06) on YouTube, Yuja Wang, Berlin Philharmonic, Paavo Järvi, 2015