A regular polyhedron is a polyhedron whose symmetry group acts transitively on its flags. A regular polyhedron is highly symmetrical, being all of edge-transitive, vertex-transitive and face-transitive. In classical contexts, many different equivalent definitions are used; a common one is that the faces are congruent regular polygons which are assembled in the same way around each vertex.

A regular polyhedron is identified by its Schläfli symbol of the form {n, m}, where n is the number of sides of each face and m the number of faces meeting at each vertex. There are 5 finite convex regular polyhedra (the Platonic solids), and four regular star polyhedra (the Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra), making nine regular polyhedra in all. In addition, there are five regular compounds of the regular polyhedra.

The regular polyhedra

[edit]There are five convex regular polyhedra, known as the Platonic solids; four regular star polyhedra, the Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra; and five regular compounds of regular polyhedra:

Platonic solids

[edit]

|

|

|

|

|

| Tetrahedron {3, 3} |

Cube {4, 3} |

Octahedron {3, 4} |

Dodecahedron {5, 3} |

Icosahedron {3, 5} |

| χ = 2 | χ = 2 | χ = 2 | χ = 2 | χ = 2 |

Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra

[edit]

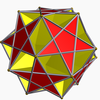

|

|

|

|

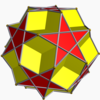

| Small stellated dodecahedron {5/2, 5} |

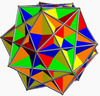

Great dodecahedron {5, 5/2} |

Great stellated dodecahedron {5/2, 3} |

Great icosahedron {3, 5/2} |

| χ = −6 | χ = −6 | χ = 2 | χ = 2 |

Regular compounds

[edit]

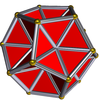

|

|

|

|

|

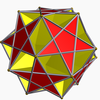

| Two tetrahedra 2 {3, 3} |

Five tetrahedra 5 {3, 3} |

Ten tetrahedra 10 {3, 3} |

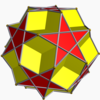

Five cubes 5 {4, 3} |

Five octahedra 5 {3, 4} |

| χ = 4 | χ = 10 | χ = 0 | χ = −10 | χ = 10 |

Characteristics

[edit]Equivalent properties

[edit]The property of having a similar arrangement of faces around each vertex can be replaced by any of the following equivalent conditions in the definition:

- The vertices of a convex regular polyhedron all lie on a sphere.

- All the dihedral angles of the polyhedron are equal

- All the vertex figures of the polyhedron are regular polygons.

- All the solid angles of the polyhedron are congruent.[1]

Concentric spheres

[edit]A convex regular polyhedron has all of three related spheres (other polyhedra lack at least one kind) which share its centre:

- An insphere, tangent to all faces.

- An intersphere or midsphere, tangent to all edges.

- A circumsphere, tangent to all vertices.

Symmetry

[edit]The regular polyhedra are the most symmetrical of all the polyhedra. They lie in just three symmetry groups, which are named after the Platonic solids:

- Tetrahedral

- Octahedral (or cubic)

- Icosahedral (or dodecahedral)

Any shapes with icosahedral or octahedral symmetry will also contain tetrahedral symmetry.

Euler characteristic

[edit]The five Platonic solids have an Euler characteristic of 2. This simply reflects that the surface is a topological 2-sphere, and so is also true, for example, of any polyhedron which is star-shaped with respect to some interior point.

Interior points

[edit]The sum of the distances from any point in the interior of a regular polyhedron to the sides is independent of the location of the point (this is an extension of Viviani's theorem.) However, the converse does not hold, not even for tetrahedra.[2]

Duality of the regular polyhedra

[edit]In a dual pair of polyhedra, the vertices of one polyhedron correspond to the faces of the other, and vice versa.

The regular polyhedra show this duality as follows:

- The tetrahedron is self-dual, i.e. it pairs with itself.

- The cube and octahedron are dual to each other.

- The icosahedron and dodecahedron are dual to each other.

- The small stellated dodecahedron and great dodecahedron are dual to each other.

- The great stellated dodecahedron and great icosahedron are dual to each other.

The Schläfli symbol of the dual is just the original written backwards, for example the dual of {5, 3} is {3, 5}.

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]Stones carved in shapes resembling clusters of spheres or knobs have been found in Scotland and may be as much as 4,000 years old. Some of these stones show not only the symmetries of the five Platonic solids, but also some of the relations of duality amongst them (that is, that the centres of the faces of the cube gives the vertices of an octahedron). Examples of these stones are on display in the John Evans room of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford University. Why these objects were made, or how their creators gained the inspiration for them, is a mystery. There is doubt regarding the mathematical interpretation of these objects, as many have non-platonic forms, and perhaps only one has been found to be a true icosahedron, as opposed to a reinterpretation of the icosahedron dual, the dodecahedron.[3]

It is also possible that the Etruscans preceded the Greeks in their awareness of at least some of the regular polyhedra, as evidenced by the discovery near Padua (in Northern Italy) in the late 19th century of a dodecahedron made of soapstone, and dating back more than 2,500 years (Lindemann, 1987).

Greeks

[edit]The earliest known written records of the regular convex solids originated from Classical Greece. When these solids were all discovered and by whom is not known, but Theaetetus (an Athenian) was the first to give a mathematical description of all five (Van der Waerden, 1954), (Euclid, book XIII). H.S.M. Coxeter (Coxeter, 1948, Section 1.9) credits Plato (400 BC) with having made models of them, and mentions that one of the earlier Pythagoreans, Timaeus of Locri, used all five in a correspondence between the polyhedra and the nature of the universe as it was then perceived – this correspondence is recorded in Plato's dialogue Timaeus. Euclid's reference to Plato led to their common description as the Platonic solids.

One might characterise the Greek definition as follows:

- A regular polygon is a (convex) planar figure with all edges equal and all corners equal.

- A regular polyhedron is a solid (convex) figure with all faces being congruent regular polygons, the same number arranged all alike around each vertex.

This definition rules out, for example, the square pyramid (since although all the faces are regular, the square base is not congruent to the triangular sides), or the shape formed by joining two tetrahedra together (since although all faces of that triangular bipyramid would be equilateral triangles, that is, congruent and regular, some vertices have 3 triangles and others have 4).

This concept of a regular polyhedron would remain unchallenged for almost 2000 years.

Regular star polyhedra

[edit]Regular star polygons such as the pentagram (star pentagon) were also known to the ancient Greeks – the pentagram was used by the Pythagoreans as their secret sign, but they did not use them to construct polyhedra. It was not until the early 17th century that Johannes Kepler realised that pentagrams could be used as the faces of regular star polyhedra. Some of these star polyhedra may have been discovered by others before Kepler's time, but Kepler was the first to recognise that they could be considered "regular" if one removed the restriction that regular polyhedra be convex. Two hundred years later Louis Poinsot also allowed star vertex figures (circuits around each corner), enabling him to discover two new regular star polyhedra along with rediscovering Kepler's. These four are the only regular star polyhedra, and have come to be known as the Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra. It was not until the mid-19th century, several decades after Poinsot published, that Cayley gave them their modern English names: (Kepler's) small stellated dodecahedron and great stellated dodecahedron, and (Poinsot's) great icosahedron and great dodecahedron.

The Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra may be constructed from the Platonic solids by a process called stellation. The reciprocal process to stellation is called facetting (or faceting). Every stellation of one polyhedron is dual, or reciprocal, to some facetting of the dual polyhedron. The regular star polyhedra can also be obtained by facetting the Platonic solids. This was first done by Bertrand around the same time that Cayley named them.

By the end of the 19th century there were therefore nine regular polyhedra – five convex and four star.

Regular polyhedra in nature

[edit]Each of the Platonic solids occurs naturally in one form or another.

The tetrahedron, cube, and octahedron all occur as crystals. These by no means exhaust the numbers of possible forms of crystals (Smith, 1982, p212), of which there are 48. Neither the regular icosahedron nor the regular dodecahedron are amongst them, but crystals can have the shape of a pyritohedron, which is visually almost indistinguishable from a regular dodecahedron. Truly icosahedral crystals may be formed by quasicrystalline materials which are very rare in nature but can be produced in a laboratory.

A more recent discovery is of a series of new types of carbon molecule, known as the fullerenes (see Curl, 1991). Although C60, the most easily produced fullerene, looks more or less spherical, some of the larger varieties (such as C240, C480 and C960) are hypothesised to take on the form of slightly rounded icosahedra, a few nanometres across.

Regular polyhedra appear in biology as well. The coccolithophore Braarudosphaera bigelowii has a regular dodecahedral structure, about 10 micrometres across.[4] In the early 20th century, Ernst Haeckel described a number of species of radiolarians, some of whose shells are shaped like various regular polyhedra.[5] Examples include Circoporus octahedrus, Circogonia icosahedra, Lithocubus geometricus and Circorrhegma dodecahedra; the shapes of these creatures are indicated by their names.[5] The outer protein shells of many viruses form regular polyhedra. For example, HIV is enclosed in a regular icosahedron, as is the head of a typical myovirus.[6][7]

-

The coccolithophore Braarudosphaera bigelowii has a regular dodecahedral structure

-

The radiolarian Circogonia icosahedra has a regular icosahedral structure

In ancient times the Pythagoreans believed that there was a harmony between the regular polyhedra and the orbits of the planets. In the 17th century, Johannes Kepler studied data on planetary motion compiled by Tycho Brahe and for a decade tried to establish the Pythagorean ideal by finding a match between the sizes of the polyhedra and the sizes of the planets' orbits. His search failed in its original objective, but out of this research came Kepler's discoveries of the Kepler solids as regular polytopes, the realisation that the orbits of planets are not circles, and the laws of planetary motion for which he is now famous. In Kepler's time only five planets (excluding the earth) were known, nicely matching the number of Platonic solids. Kepler's work, and the discovery since that time of Uranus and Neptune, have invalidated the Pythagorean idea.

Around the same time as the Pythagoreans, Plato described a theory of matter in which the five elements (earth, air, fire, water and spirit) each comprised tiny copies of one of the five regular solids. Matter was built up from a mixture of these polyhedra, with each substance having different proportions in the mix. Two thousand years later Dalton's atomic theory would show this idea to be along the right lines, though not related directly to the regular solids.

Further generalisations

[edit]The 20th century saw a succession of generalisations of the idea of a regular polyhedron, leading to several new classes.

Regular skew apeirohedra

[edit]In the first decades, Coxeter and Petrie allowed "saddle" vertices with alternating ridges and valleys, enabling them to construct three infinite folded surfaces which they called regular skew polyhedra.[8] Coxeter offered a modified Schläfli symbol {l,m|n} for these figures, with {l,m} implying the vertex figure, with m regular l-gons around a vertex. The n defines n-gonal holes. Their vertex figures are regular skew polygons, vertices zig-zagging between two planes.

| Infinite regular skew polyhedra in 3-space (partially drawn) | ||

|---|---|---|

{4,6|4} |

{6,4|4} |

{6,6|3} |

Regular skew polyhedra

[edit]Finite regular skew polyhedra exist in 4-space. These finite regular skew polyhedra in 4-space can be seen as a subset of the faces of uniform 4-polytopes. They have planar regular polygon faces, but regular skew polygon vertex figures.

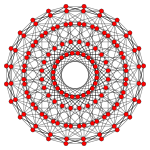

Two dual solutions are related to the 5-cell, two dual solutions are related to the 24-cell, and an infinite set of self-dual duoprisms generate regular skew polyhedra as {4, 4 | n}. In the infinite limit these approach a duocylinder and look like a torus in their stereographic projections into 3-space.

| Orthogonal Coxeter plane projections | Stereographic projection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A4 | F4 | |||

|

|

|

|

|

| {4, 6 | 3} | {6, 4 | 3} | {4, 8 | 3} | {8, 4 | 3} | {4, 4 | n} |

| 30 {4} faces 60 edges 20 vertices |

20 {6} faces 60 edges 30 vertices |

288 {4} faces 576 edges 144 vertices |

144 {8} faces 576 edges 288 vertices |

n2 {4} faces 2n2 edges n2 vertices |

Regular polyhedra in non-Euclidean and other spaces

[edit]Studies of non-Euclidean (hyperbolic and elliptic) and other spaces such as complex spaces, discovered over the preceding century, led to the discovery of more new polyhedra such as complex polyhedra which could only take regular geometric form in those spaces.

Regular polyhedra in hyperbolic space

[edit]

In H3 hyperbolic space, paracompact regular honeycombs have Euclidean tiling facets and vertex figures that act like finite polyhedra. Such tilings have an angle defect that can be closed by bending one way or the other. If the tiling is properly scaled, it will close as an asymptotic limit at a single ideal point. These Euclidean tilings are inscribed in a horosphere just as polyhedra are inscribed in a sphere (which contains zero ideal points). The sequence extends when hyperbolic tilings are themselves used as facets of noncompact hyperbolic tessellations, as in the heptagonal tiling honeycomb {7,3,3}; they are inscribed in an equidistant surface (a 2-hypercycle), which has two ideal points.

Regular tilings of the real projective plane

[edit]Another group of regular polyhedra comprise tilings of the real projective plane. These include the hemi-cube, hemi-octahedron, hemi-dodecahedron, and hemi-icosahedron. They are (globally) projective polyhedra, and are the projective counterparts of the Platonic solids. The tetrahedron does not have a projective counterpart as it does not have pairs of parallel faces which can be identified, as the other four Platonic solids do.

Hemi-cube {4,3} |

Hemi-octahedron {3,4} |

Hemi-dodecahedron {3,5} |

Hemi-icosahedron {5,3} |

These occur as dual pairs in the same way as the original Platonic solids do. Their Euler characteristics are all 1.

Abstract regular polyhedra

[edit]By now, polyhedra were firmly understood as three-dimensional examples of more general polytopes in any number of dimensions. The second half of the century saw the development of abstract algebraic ideas such as Polyhedral combinatorics, culminating in the idea of an abstract polytope as a partially ordered set (poset) of elements. The elements of an abstract polyhedron are its body (the maximal element), its faces, edges, vertices and the null polytope or empty set. These abstract elements can be mapped into ordinary space or realised as geometrical figures. Some abstract polyhedra have well-formed or faithful realisations, others do not. A flag is a connected set of elements of each dimension – for a polyhedron that is the body, a face, an edge of the face, a vertex of the edge, and the null polytope. An abstract polytope is said to be regular if its combinatorial symmetries are transitive on its flags – that is to say, that any flag can be mapped onto any other under a symmetry of the polyhedron. Abstract regular polytopes remain an active area of research.

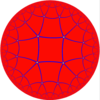

Five such regular abstract polyhedra, which can not be realised faithfully, were identified by H. S. M. Coxeter in his book Regular Polytopes (1977) and again by J. M. Wills in his paper "The combinatorially regular polyhedra of index 2" (1987). All five have C2×S5 symmetry but can only be realised with half the symmetry, that is C2×A5 or icosahedral symmetry.[9][10][11] They are all topologically equivalent to toroids. Their construction, by arranging n faces around each vertex, can be repeated indefinitely as tilings of the hyperbolic plane. In the diagrams below, the hyperbolic tiling images have colors corresponding to those of the polyhedra images.

Polyhedron

Medial rhombic triacontahedron

Dodecadodecahedron

Medial triambic icosahedron

Ditrigonal dodecadodecahedron

Excavated dodecahedronType Dual {5,4}6 {5,4}6 Dual of {5,6}4 {5,6}4 {6,6}6 (v,e,f) (24,60,30) (30,60,24) (24,60,20) (20,60,24) (20,60,20) Vertex figure {5}, {5/2}

(5.5/2)2

{5}, {5/2}

(5.5/3)3

Faces 30 rhombi

12 pentagons

12 pentagrams

20 hexagons

12 pentagons

12 pentagrams

20 hexagrams

Tiling

{4, 5}

{5, 4}

{6, 5}

{5, 6}

{6, 6}χ −6 −6 −16 −16 −20

Petrie dual

[edit]The Petrie dual of a regular polyhedron is a regular map whose vertices and edges correspond to the vertices and edges of the original polyhedron, and whose faces are the set of skew Petrie polygons.[12]

| Name | Petrial tetrahedron |

Petrial cube | Petrial octahedron | Petrial dodecahedron | Petrial icosahedron |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | {3,3}π | {4,3}π | {3,4}π | {5,3}π | {3,5}π |

| (v,e,f), χ | (4,6,3), χ = 1 | (8,12,4), χ = 0 | (6,12,4), χ = −2 | (20,30,6), χ = −4 | (12,30,6), χ = −12 |

| Faces | 3 skew squares

|

4 skew hexagons | 6 skew decagons | ||

|

|

|

| ||

| Image |

|

|

|

|

|

| Animation |

|

|

|

|

|

| Related figures |

{4,3}3 = {4,3}/2 = {4,3}(2,0) |

{6,3}3 = {6,3}(2,0) |

{6,4}3 = {6,4}(4,0) |

{10,3}5 | {10,5}3 |

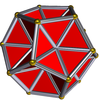

Spherical polyhedra

[edit]The usual five regular polyhedra can also be represented as spherical tilings (tilings of the sphere):

Tetrahedron {3,3} |

Cube {4,3} |

Octahedron {3,4} |

Dodecahedron {5,3} |

Icosahedron {3,5} |

Small stellated dodecahedron {5/2,5} |

Great dodecahedron {5,5/2} |

Great stellated dodecahedron {5/2,3} |

Great icosahedron {3,5/2} |

Regular polyhedra that can only exist as spherical polyhedra

[edit]For a regular polyhedron whose Schläfli symbol is {m, n}, the number of polygonal faces may be found by:

The Platonic solids known to antiquity are the only integer solutions for m ≥ 3 and n ≥ 3. The restriction m ≥ 3 enforces that the polygonal faces must have at least three sides.

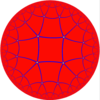

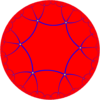

When considering polyhedra as a spherical tiling, this restriction may be relaxed, since digons (2-gons) can be represented as spherical lunes, having non-zero area. Allowing m = 2 admits a new infinite class of regular polyhedra, which are the hosohedra. On a spherical surface, the regular polyhedron {2, n} is represented as n abutting lunes, with interior angles of 2π/n. All these lunes share two common vertices.[13]

A regular dihedron, {n, 2}[13] (2-hedron) in three-dimensional Euclidean space can be considered a degenerate prism consisting of two (planar) n-sided polygons connected "back-to-back", so that the resulting object has no depth, analogously to how a digon can be constructed with two line segments. However, as a spherical tiling, a dihedron can exist as nondegenerate form, with two n-sided faces covering the sphere, each face being a hemisphere, and vertices around a great circle. It is regular if the vertices are equally spaced.

Digonal dihedron {2,2} |

Trigonal dihedron {3,2} |

Square dihedron {4,2} |

Pentagonal dihedron {5,2} |

Hexagonal dihedron {6,2} |

... | {n,2} |

Digonal hosohedron {2,2} |

Trigonal hosohedron {2,3} |

Square hosohedron {2,4} |

Pentagonal hosohedron {2,5} |

Hexagonal hosohedron {2,6} |

... | {2,n} |

The hosohedron {2,n} is dual to the dihedron {n,2}. Note that when n = 2, we obtain the polyhedron {2,2}, which is both a hosohedron and a dihedron. All of these have Euler characteristic 2.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cromwell, Peter R. (1997). Polyhedra. Cambridge University Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-521-66405-5.

- ^ Chen, Zhibo, and Liang, Tian. "The converse of Viviani's theorem", The College Mathematics Journal 37(5), 2006, pp. 390–391.

- ^ The Scottish Solids Hoax.

- ^ Hagino, K., Onuma, R., Kawachi, M. and Horiguchi, T. (2013) "Discovery of an endosymbiotic nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium UCYN-A in Braarudosphaera bigelowii (Prymnesiophyceae)". PLoS One, 8(12): e81749. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0081749.

- ^ a b Haeckel, E. (1904). Kunstformen der Natur. Available as Haeckel, E. Art forms in nature, Prestel USA (1998), ISBN 3-7913-1990-6. Online version at Kurt Stüber's Biolib (in german)

- ^ "Myoviridae". Virus Taxonomy. Elsevier. 2012. pp. 46–62. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-384684-6.00002-1. ISBN 9780123846846.

- ^ STRAUSS, JAMES H.; STRAUSS, ELLEN G. (2008). "The Structure of Viruses". Viruses and Human Disease. Elsevier. pp. 35–62. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-373741-0.50005-2. ISBN 9780123737410. S2CID 80803624.

- ^ Coxeter, The Beauty of Geometry: Twelve Essays, Dover Publications, 1999, ISBN 0-486-40919-8 (Chapter 5: Regular Skew Polyhedra in three and four dimensions and their topological analogues, Proceedings of the London Mathematics Society, Ser. 2, Vol 43, 1937.)

- ^ The Regular Polyhedra (of index two), David A. Richter

- ^ Cutler, Anthony M.; Schulte, Egon (2010). "Regular Polyhedra of Index Two, I". arXiv:1005.4911 [math.MG].

- ^ Regular Polyhedra of Index Two, II Beitrage zur Algebra und Geometrie 52(2):357–387 · November 2010, Table 3, p.27

- ^ McMullen, Peter; Schulte, Egon (2002), Abstract Regular Polytopes, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, vol. 92, Cambridge University Press, p. 192, ISBN 9780521814966

- ^ a b Coxeter, Regular polytopes, p. 12

- Bertrand, J. (1858). Note sur la théorie des polyèdres réguliers, Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Sciences, 46, pp. 79–82.

- Haeckel, E. (1904). Kunstformen der Natur. Available as Haeckel, E. Art forms in nature, Prestel USA (1998), ISBN 3-7913-1990-6, or online at http://caliban.mpiz-koeln.mpg.de/~stueber/haeckel/kunstformen/natur.html

- Smith, J. V. (1982). Geometrical And Structural Crystallography. John Wiley and Sons.

- Sommerville, D. M. Y. (1930). An Introduction to the Geometry of n Dimensions. E. P. Dutton, New York. (Dover Publications edition, 1958). Chapter X: The Regular Polytopes.

- Coxeter, H.S.M.; Regular Polytopes (third edition). Dover Publications Inc. ISBN 0-486-61480-8