Republican Congress An Chomhdháil Phoblachtach | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founder | Peadar O'Donnell |

| Founded | 1934 |

| Dissolved | 1936 |

| Split from | Irish Republican Army |

| Paramilitary wing | Connolly Column (1936) Irish Citizen Army |

| Ideology | Factions: |

| Political position | Far-left |

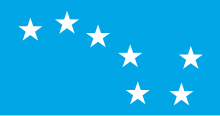

| Colours | Blue and white |

| Party flag | |

Starry Plough of the Congress | |

| Part of a series on |

| Irish republicanism |

|---|

|

The Republican Congress (Irish: An Chomhdháil Phoblachtach) was an Irish republican political organisation founded in 1934, when pro-communist republicans left the Anti-Treaty Irish Republican Army. The Congress was led by such anti-Treaty veterans as Peadar O'Donnell, Frank Ryan and George Gilmore. In their later phase they were involved with the Communist International and International Brigades paramilitary; the Connolly Column.

The group claimed: "We believe that a republic of a united Ireland will never be achieved except through a struggle which uproots capitalism on its way."[1] They were not a political party as such, but rather an extraparliamentary organisation dedicated to creating a "workers' republic," which leaned towards the Communist Party of Ireland. They split mostly over whether they should be a party in their own right.

History

[edit]Background

[edit]A group of republicans had founded a party, Saor Éire, in 1931, but it was banned later in the year. Despite this, many figures on the left wing of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) felt that the creation of a new party remained a priority, as they feared that supporters would otherwise turn to Fianna Fáil and the Communist Party of Ireland. The IRA organised a convention of its members in March 1934, which voted against creating a new party by a majority of one.[2] The supporters of a new party, including Ryan, Michael Price, Gilmore, O'Donnell and Mick Fitzgerald, then walked out, and proceeded to create a new organisation.[3]

Establishment

[edit]On 8 April 1934, the founding conference of the Republican Congress party was held in Athlone, and a head office was established on Pearse Street in Dublin. The IRA published a statement which described the new party as "an attack by Republicans [which] can only assist the campaign of the Capitalist and Imperialist elements", and stating that they expected the party would soon drop abstentionism towards the Dáil. The former IRA members in the party leadership were expelled from the paramilitary organisation, but some less prominent figures, including Sheila Humphreys, Eithnie Coyle, Charles Reynolds, Seamus de Burca and George Leonard withdrew once they saw the IRA statement. However, other IRA members were won over and joined the Congress, including Liam Kelly, Joseph Doyle, Nora Connolly O'Brien and Roddy Connolly.[3]

During this time, those involved in the Republican Congress developed the concept of a "triple alliance" that would need to unite to advance the workers' cause in Ireland: A socialist Party, a paramilitary force and one big union. The socialist party would, of course, be the Republic Congress itself whilst the "One Big Union" (a concept taken from Industrial Workers of the World) would be ITGWU. As for the paramilitary force, the Republican Congress set about reviving James Connolly's Irish Citizen Army which had been largely inactive since 1919. Frank Ryan and Michael Price were amongst Congress members set to the task and they quickly made headway, with an estimated 300 members brought under the ICA banner in 1934.[4]

Two councillors were elected as Republican Congress candidates in Westmeath and Dundalk in 1934. At the Republican rally at Bodenstown in 1934, clashes occurred between Republican Congress supporters and IRA members. Congress supporters among the crowd of about 17,000 were estimated at between 600 and 2,000. The IRA leadership did not authorise banners other than its own and ordered the Congress banners to be seized. The clash was given a sectarian element by the attack on 36 Congress members from the predominantly Loyalist parts of West Belfast – they formed the Shankill Road branch – who carried a banner reading, "Unite Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter to break the connection with Capitalism".

Infighting and Demise

[edit]Following moderate success in agitating on behalf of the workers the Congress split at its first annual conference held in Rathmines Town Hall on September 8–9, 1934. The split occurred mainly due to organisational disunity between two factions. One side, which included the likes of Peadar O'Donnell,[5] Frank Ryan and George Gilmore[6] believed that a popular front of left-wing republicans could challenge the dominance of the mainstream political parties and form a "republic". The opposing faction, which included Roddy Connolly[7] and Michael Price, believed that a political party should be formed in order to fight for a "workers' republic". Those calling for a Popular Front won a vote on the matter and in response, those calling for a "Workers' Republic", including Price, withdrew their support and left the Congress.[3]

The group went into decline thereafter. An attempt to form a 100-member military-style organisation to infiltrate the political, social and trade union movements came to nothing, and in 1936 the party ran out of money. It briefly replaced its weekly newspaper, Republican Congress, with a new publication, the Irish People, but this made no difference, and the party office closed down. Despite this, the remaining leaders worked with the Community Party of Ireland to hold a series of public meetings, led by Willie Gallacher from the Communist Party of Great Britain, but following crowd trouble, these were abandoned, and the group undertook no public activities after November 1936.[3]

The Congress had its last hurrah on the battlefields of the Spanish Civil War when a group of Irishmen fought for the Second Spanish Republic as part of the Communist International Brigades.

Members

[edit]- Roddy Connolly

- Nora Connolly O'Brien

- Eithne Coyle - Joined the Congress but quickly resigned after members of Cumann na mBan expressed contention

- Peter Daly

- Charles Donnelly

- Frank Edwards

- George Gilmore

- Victor Halley

- Sheila Humphreys - Joined the Congress but quickly resigned after members of Cumann na mBan expressed contention

- William McCullough

- Seán McLoughlin

- William McMullen - Cited in some sources as Chairman[8]

- Peter O'Connor

- Gearóid Ó Cuinneagáin - Served as an editorial writer of the Republican Congress's Irish language newspaper An tÉireannach. However, he resigned after a few months and later came to renounce socialism in favour of Fascism. Would go on to found Ailtirí na hAiséirghe.

- Peadar O'Donnell

- Michael O'Riordan

- Thomas Patten

- Mick Price

- Frank Ryan

- Jack White

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Athlone Manifesto (8 April 1934), quoted in Republican Congress 5 May 1934

- ^ MacEoin, Uinseann (1997). The IRA in the Twilight Years: 1923–1948. Dublin: Argenta. p. 10. ISBN 9780951117248.

- ^ a b c d Tim Pat Coogan, The IRA, pp.79-84

- ^ "The Irish Citizens' Army". SIPTU.ie. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ White, Lawrence William (July 2005). "Peadar O'Donnell, 'Real Republicanism' and The Bell". Retrieved 24 March 2021.

Republican Congress divided at its first national conference between those who wished to launch a new socialist political party seeking as an immediate objective a 'workers' republic' and those who, following O'Donnell, wished the new venture to remain what it was: a congress, a coming together of all republican opinion representing disparate organisations, to pursue the common objective of 'the republic'.

- ^ Diarmaid Ferriter (October 2009). "Gilmore, George Frederick". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ Byrne, Patrick. "The Irish Republican Congress Revisited". Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ "McMullen, William". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- Brian Hanley, The IRA 1926-1936

- Sean Cronin, Frank Ryan: The Search for the Republic

- Donal O'Drisceoil, Peadar O'Donnell

- Paddy Bryne - "Memoirs of the Republic Congress"

- Eugene Downing, a CPI member was interviewed and describes the Bodenstown episode of 1934