Risk communication is a complex cross-disciplinary academic field that is part of risk management and related to fields like crisis communication. The goal is to make sure that targeted audiences understand how risks affect them or their communities by appealing to their values.[1][2]

Risk communication is particularly important in disaster preparedness,[3] public health,[4] and preparation for major global catastrophic risk.[3] For example, the impacts of climate change and climate risk effect every part of society, so communicating that risk is an important climate communication practice, in order for societies to plan for climate adaptation.[5] Similarly, in pandemic prevention, understanding of risk helps communities stop the spread of disease and improve responses.[6]

Risk communication deals with possible risks and aims to raise awareness of those risks to encourage or persuade changes in behavior to relieve threats in the long term. On the other hand, crisis communication is aimed at raising awareness of a specific type of threat, the magnitude, outcomes, and specific behaviors to adopt to reduce the threat.[7]

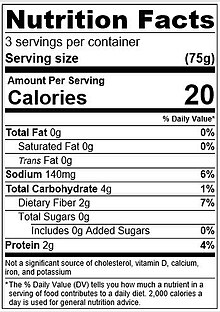

Risk communication in food safety is part of the risk analysis framework. Together with risk assessment and risk management, risk communication aims to reduce foodborne illnesses. Food safety risk communication is an obligatory activity for food safety authorities[8] in countries, which adopted the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures.

Risk communication also exists on a smaller scale. For instance, the risks associated with personal medical decisions have to be communicated to that individual along with their family.[9]

Types

[edit]Risk communication takes place on different scales, of which have different features and methods.

Community risk communication

[edit]Risk communication on a community-wide scale mainly falls into specific categories. Some of the most well-studied areas of risk communication are climate change, nutrition, and natural disasters like floods.[10]

With the rise of COVID-19 in 2019, risk communication strategies utilized by governments to their communities were heavily critiqued.[11] In the modern day, most people in groups get their information from the internet before anything else, so the sending of risk communication messages has methodologically changed.[12]

Individual risk communication

[edit]One of the most common causes for the enactment of risk communication is medical-based personal issues. In a 2015 study, risk communication to people who had family members with dementia took place, and a model was developed that heavily features shared decision-making processes.[9] In these cases where families of patients are involved, there is no general message that is sent out to the public. Instead, what often happens is that an intervention takes place between the medical experts and the family.[13]

Methods

[edit]Risk communication and community engagement

[edit]Risk communication and community engagement (RCCE) is a method that draws heavily on volunteers, frontline personnel and on people without prior training in this area.[14] The World Health Organization advocated for this approach during the early recommendations for public health mitigation of the COVID-19 pandemic.[15]

Substantive harm analysis

[edit]Another way to do risk communication analysis is to test the risks. Specifically, testing on the four main types of harm outlined by Löfstedt. These four types of harm, in relation to risk communication, are death, illness or injury, lack of resources, and injury to social status. The next step is then to test those risks of harm in three different fields to get a sense of the overall scope of the possible harm.[16]

Challenges

[edit]Problems for risk communicators involve how to reach the intended audience, how to make the risk comprehensible and relatable to other risks, how to pay appropriate respect to the audience's values related to the risk, how to predict the audience's response to the communication, etc. A main goal of risk communication is to improve collective and individual decision making.

Some experts coincide that risk is not only enrooted in the communication process but also it cannot be dissociated from the use of language.[17] Though each culture develops its own fears and risks, these construes apply only by the hosting culture. These differences stem from epistemological barriers, as well as social construction ones.[18] When there are varying community-based beliefs in a situation, the importance of the risk at hand is also varied, as different communities have different perceptions of how impactful a result might be.[18]

Government risk communication

[edit]

Some challenges with risk communication by governments stems from whether or not the communities being communicated to even want to know about the risks they are facing. In a 2013 study, Canadian citizens reacted positively when their government communicated risks they had individual control over, but found communicating minute risks that had no individual control over irrelevant and unnecessary.[19] When someone is irritated by a risk communication message, it is likely that their "gut feeling" is impacted, leading to a possible misunderstanding of the situation.[20]

Nutrition risk communication

[edit]Unlike other risk communication areas, there is not a definite unambiguous relationship between the intake of food and the effect on the human body. This has led to conflicts between suppliers and consumers when a controversy comes to light. Among professional nutritionists, there is debate on whether certain diets or foods are in fact good or bad for humans, as everyone's body can react differently to food intake.[21] Studies have retained that nutrition risk communication has been poor over time, as the strategies employed may be too similar to those employed in nuclear disaster situations.[22] When this strategy is employed, those who receive the risk communication messages can become irritated, as they feel the actual scope of the danger does not match the message.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ Risk Communication Primer—Tools and Techniques. Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center

- ^ Understanding Risk Communication Theory: A Guide for Emergency Managers and Communicators. Report to Human Factors/Behavioral Sciences Division, Science and Technology Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security (May 2012)

- ^ a b Rahman, Alfi; Munadi, Khairul (2019). "Communicating Risk in Enhancing Disaster Preparedness: A Pragmatic Example of Disaster Risk Communication Approach from the Case of Smong Story". IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 273 (1): 012040. Bibcode:2019E&ES..273a2040R. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/273/1/012040. S2CID 199164028.

- ^ Motarjemi, Y.; Ross, T (2014-01-01), "Risk Analysis: Risk Communication: Biological Hazards", in Motarjemi, Yasmine (ed.), Encyclopedia of Food Safety, Waltham: Academic Press, pp. 127–132, ISBN 978-0-12-378613-5, retrieved 2021-11-12

- ^ "Risk communication in the context of climate change". weADAPT | Climate change adaptation planning, research and practice. 2011-03-25. Retrieved 2021-11-12.

- ^ "RISK COMMUNICATION SAVES LIVES & LIVELIHOODS Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Framework" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2015.

- ^ REYNOLDS, BARBARA; SEEGER, MATTHEW W. (2005-02-23). "Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication as an Integrative Model". Journal of Health Communication. 10 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1080/10810730590904571. ISSN 1081-0730. PMID 15764443. S2CID 16810613.

- ^ Kasza, Gyula; Csenki, Eszter; Szakos, Dávid; Izsó, Tekla (2022-08-01). "The evolution of food safety risk communication: Models and trends in the past and the future". Food Control. 138: 109025. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2022.109025. ISSN 0956-7135. S2CID 248223805.

- ^ a b Stevenson, Mabel; Taylor, Brian J. (2018-06-03). "Risk communication in dementia care: family perspectives". Journal of Risk Research. 21 (6): 692–709. doi:10.1080/13669877.2016.1235604. ISSN 1366-9877. S2CID 152134132.

- ^ Snel, Karin A. W.; Witte, Patrick A.; Hartmann, Thomas; Geertman, Stan C. M. (2019-07-04). "More than a one-size-fits-all approach – tailoring flood risk communication to plural residents' perspectives". Water International. 44 (5): 554–570. Bibcode:2019WatIn..44..554S. doi:10.1080/02508060.2019.1663825. ISSN 0250-8060. S2CID 211381061.

- ^ Krause, Nicole M.; Freiling, Isabelle; Beets, Becca; Brossard, Dominique (2020-08-02). "Fact-checking as risk communication: the multi-layered risk of misinformation in times of COVID-19". Journal of Risk Research. 23 (7–8): 1052–1059. doi:10.1080/13669877.2020.1756385. ISSN 1366-9877. S2CID 219097127.

- ^ Chesser, Amy; Drassen Ham, Amy; Keene Woods, Nikki (2020). "Assessment of COVID-19 Knowledge Among University Students: Implications for Future Risk Communication Strategies". Health Education & Behavior. 47 (4): 540–543. doi:10.1177/1090198120931420. ISSN 1090-1981. PMID 32460566. S2CID 218976132.

- ^ Edwards, A.; Elwyn, G. (2001-09-01). "Understanding risk and lessons for clinical risk communication about treatment preferences". BMJ Quality & Safety. 10 (suppl 1): i9 – i13. doi:10.1136/qhc.0100009. ISSN 2044-5415. PMC 1765742. PMID 11533431.

- ^ "Risk Communication and Community Engagement (RCCE) Considerations: Ebola Response in the Democratic Republic of the Congo". WHO. 2018. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19 Global Risk Communication and Community Engagement Strategy – interim guidance". www.who.int. Retrieved 2021-11-12.

- ^ Löfstedt, Ragnar; Perri (2008). "What environmental and technological risk communication research and health risk research can learn from each other". Journal of Risk Research. 11 (1): 141–167. doi:10.1080/13669870701797137. ISSN 1366-9877. S2CID 143576155.

- ^ Kerr, Richard A. (2007-06-08). "Pushing the Scary Side of Global Warming". Science. 316 (5830): 1412–1415. doi:10.1126/science.316.5830.1412. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17556560. S2CID 153495152.

- ^ a b Stoffle, Richard; Minnis, Jessica (2008-01-01). "Resilience at risk: epistemological and social construction barriers to risk communication". Journal of Risk Research. 11 (1–2): 55–68. doi:10.1080/13669870701521479. hdl:10150/292434. ISSN 1366-9877. S2CID 53618514.

- ^ Markon, Marie-Pierre L.; Crowe, Joshua; Lemyre, Louise (2013-06-01). "Examining uncertainties in government risk communication: citizens' expectations". Health, Risk & Society. 15 (4): 313–332. doi:10.1080/13698575.2013.796344. ISSN 1369-8575. S2CID 56501360.

- ^ a b Visschers, Vivianne; Meertens, Ree; Passchier, Wim; de Vries, Nanne (2008-01-01). "Audiovisual risk communication unravelled: effects on gut feelings and cognitive processes". Journal of Risk Research. 11 (1): 207–221. doi:10.1080/13669870801947954. ISSN 1366-9877. S2CID 144040392.

- ^ Renn, Ortwin (2006-12-01). "Risk Communication – Consumers Between Information and Irritation". Journal of Risk Research. 9 (8): 833–849. doi:10.1080/13669870601010938. ISSN 1366-9877. S2CID 56239032.

- ^ Lofstedt, Ragnar E. (2006-12-01). "How can we Make Food Risk Communication Better: Where are we and Where are we Going?". Journal of Risk Research. 9 (8): 869–890. doi:10.1080/13669870601065585. ISSN 1366-9877. S2CID 216091121.