Robert Persons SJ (24 June 1546 – 15 April 1610),[1] later known as Robert Parsons, was an English Jesuit priest. He was a major figure in establishing the 16th-century "English Mission" of the Society of Jesus.

Early life

[edit]Robert Persons was born at Nether Stowey, Somerset, to yeoman parents. Through the favour of local parson named John Hayward, a former monk, he was educated in 1562 at St. Mary's Hall, Oxford. After completing his degrees with distinction, he became a fellow and tutor at Balliol in 1568.[2]

College fellow and priest

[edit]As a Fellow of Balliol College, Persons clashed with the Master there, Adam Squire, and also the academic and Roman Catholic priest Christopher Bagshaw.[1] On 13 February 1574, he was subsequently forced to resign. Through discussion and encouraged by pupillage with Father William Good, SJ, he travelled overseas to become a Jesuit priest at St Paul's, Rome on 3 July 1575.

English mission: 1580–1581

[edit]Persons accompanied Edmund Campion on his mission to fellow English Catholics in 1580. The Jesuit General, Everard Mercurian, had been reluctant to involve the Society directly in English ecumenical affairs. He was persuaded by an Italian Jesuit provincial, and later by Superior General Claudio Acquaviva, after William Cardinal Allen had found Mercurian resistant to change in October 1579.[3] Persons fast tracked English recruits to the Jesuits, and planned to set up cooperation with the remaining English secular clergy. He became impatient with Father Good's approach to the situation. Campion was much less of an enthusiast than he was.[4]

The mission was immediately compromised as the pope had sent a separate group to the Jesuit mission[clarification needed], to support the Irish rebel, James FitzMaurice FitzGerald. Persons and Campion only learned of this event in Reims while they were en route to England. After the initial invasion force under the mercenary Thomas Stukley had achieved nothing successful in 1578, the intervention under FitzGerald caused the English authorities to monitor the recusants closely, and try to finance the campaign against the papal forces with exactions from them.[5] Campion and Persons crossed separately into England.[3]

In June 1580 Thomas Pounde, then in the Marshalsea Prison, went to speak to Persons[how?]. This action then resulted in a petition from Pounde to the Privy Council to allow a disputation where the Jesuits would take on Robert Crowley and Henry Tripp, who used to preach to the Marshalsea inmates. Campion and Persons also prepared their own personal statements, to be kept in reserve. The immediate consequence was that Pounde was then transferred to Bishop's Stortford Castle; but the prepared statement by Campion was later circulated soon after his capture.[6]

Much of the time Persons spent in England was taken up with covert printing, and pamphleteering. He made his negative view on church papism clear to the local Catholic clergy, before a synod in Southwark. The secret printing press needed to be relocated, moving it in early 1581 to Stonor Park. Campion was captured in July of that year; and then Stephen Brinkley, who ran the printing press, was taken captive in August. Quite soon after that date Persons left for France.[3] His underlying strategy of trying to embarrass the English government by demanding a forum for his ideals was consistent with the general approach of Allen and Persons, but met with much criticism from the Catholic members. Allen and Parsons persisted with their demand for another two years, but Jesuit opinion was against further confrontation. Campion was forced into disputation in the Tower of London under adverse conditions.[7] When Persons left England, he was never to return.[1]

To the Armada

[edit]Robert Persons spent the winter of 1581–82 at Rouen, and embarked on writing projects. He was in close contact with Henry I, Duke of Guise, and through the Duke founded a school for English boys at Eu, on the coast to the north-east. Father William Creighton, SJ, was on the way to Scotland. He arrived in January 1582 and was briefed by Persons and the duke. In April Creighton returned with word from Esmé Stewart, 1st Duke of Lennox; and they went to Paris to confer with William Allen, James Beaton and Claude Mathieu, Jesuit provincial in France, on his military plans and the imprisoned Mary, Queen of Scots. The scheme, which Persons supported confidently, advanced further, but was stopped after the raid of Ruthven of August 1582. One consequence was that Allen was made Cardinal, as Persons had recommended.[1]

A new enterprise was projected for September 1583, this time through England. Persons was sent by the Duke of Guise with written instructions to Rome. He returned to Flanders, and stayed for some time at the court of the Duke of Parma. The discovery of the Throckmorton Plot disrupted the plan, and the Duke of Guise became absorbed in French domestic affairs. Philip II of Spain took over the lead, placed the Duke of Parma in charge, and limited involvement to Persons, Allen, and Hew Owen.[1]

It was during this period that Persons was involved in the work later known as Leicester's Commonwealth. Distributed covertly, it came to light in 1584. Persons is now generally thought not to be the author.[3] The British historian John Bossy of the University of York was inclined to disagree.[8]

There is a scholarly consensus that the intention was to affect French domestic politics, strengthening the Guise faction against Anglophiles. Correspondingly his[whose?] own standing suffered in some quarters.[3] Claudio Acquaviva by the end of the year was concerned that the Jesuit strategies for France and the English mission would turn out to be inconsistent in the longer term, and consulted Pope Gregory XIII on the matter. Persons as his subordinate had been told to drop plans to assassinate Elizabeth.[9]

In September 1585, Persons and Allen went to Rome after Pope Sixtus V succeeded Pope Gregory XIII. Persons was still there when the Spanish Armada sailed in 1588. At this period Allen and Persons made a close study of the succession to Elizabeth I of England, working with noted genealogist Robert Heighinton.[1] Persons took his vows of final profession in the Jesuits in Rome on 7 May 1587.

Later life

[edit]Robert Persons was sent to Spain at the close of 1588 to conciliate Philip II of Spain, who was offended[why?] with Claudio Acquaviva. Persons was successful, and then made use of the royal favour to found the seminaries of Valladolid, Seville, and Madrid (1589, 1592, 1598) and the residences of San Lucar and of Lisbon (which became a college in 1622). He then succeeded in establishing at St Omer (1594) a larger institution to which the boys from Eu were transferred. It is the institutional ancestor of Stonyhurst College.[2]

In 1596, in Seville, he wrote Memorial for the Reformation of England, which gave in some detail a blueprint for the kind of society England was to become after its return to the faith. He had hoped to succeed Allen as Cardinal on the latter's death.

Persons was, in 1605, the year of the Gunpowder Plot, the leading Jesuit priest in England. As religious tensions escalated, and Edward Coke pressed to establish the supremacy of the common law over the ecclesiastical jurisdiction, Robert Persons published his polemical response An Answere to the Fifth Part of the Reports, disputing the historical accuracy of Coke's claims about the common law in his report on Caudry's Case, especially the claim that a Tudor era statute asserting the Supremacy of the Crown was based on pre-Conquest common law, pointing to a lack of evidence for authoritative statutes before the reign of Henry III.[10]

He had hoped to succeed Allen as Cardinal on the latter's death. Unsuccessful, he was rewarded with the rectorship of the English College in Rome, where he died at the age of 63. John Donne's Pseudo Martyr (1610) engages critically with Persons' views.

Works

[edit]Robert Persons's published works were:[1]

- A brief discovrs contayning certayne reasons why Catholiques refuse to goe to Church . . . dedicated by I. H. to the queenes most excellent Maiestie. Doway, John Lyon [London], 1580. This work was published through a clandestine printing press in London, printed as a consequence of decisions at a synod at Southwark held not long after Frs. Persons and Campion landed. It was aimed at implementing a 1563 declaration of Pope Pius IV that Catholics should not mix with heretics.[11]

- A Discouerie of I. Nicols, minister, misreported a Jesuite, latelye recanted in the Tower of London. Doway [London], 1580. Printed by Persons at Stonor Park, it concerned a renegade Catholic priest.[12] In a poem which begins, Gwrandewch ddatcan, meddwl maith ("Hear a song, a great thought,"), St. Richard Gwyn, who was Canonized in 1970 as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales, both summarized Fr. Persons' work and rendered it into a work of Welsh poetry in strict meter. All of the reasons given by Fr. Persons for Catholics to refuse to attend Anglican services were listed by St. Richard Gwyn in the poem, "but of course only in brief poetic way."[13]

- A briefe censure upon two bookes written in answer to M. Edmund Campians offer of disputation. Doway, John Lyon [really at Mr. Brooke's house near London], 1581. Against William Charke and Meredith Hanmer, who had engaged in controversy with Campion.[12]

- De persecvtione Anglicana commentariolus a collegio Anglicano Romano hoc anno 1582 in vrbe editus et iam denuo Ingolstadii excusus . . . anno eodem. Also, De persecutione Angl. libellus, Romæ, ex typogr. G. Ferrarii, 1582.

- A Defence of the censvre gyven vpon tvvo bookes of William Charke and Meredith Hanmer, mynysters, 1582.

- The first booke of the Christian exercise, appertayning to Resolution [Rouen], 1582. Preface signed R. P. Afterwards much enlarged, under the title of A Christian Directorie, guiding men to their saluation, devided into three books, anno 1585, and often reprinted (40 editions by 1640). This was a major devotional work in English, and was soon adapted by Edmund Bunny to Protestant needs.[14]

- Relacion de algunos martyres ... en Inglaterra, traduzida en Castellano, 1590. William Thomas Lowndes considered that Persons was the probable author of this work on the English martyrs, as well as its translator into Spanish.[15]

- Elizabethæ Angliæ reginæ hæresim Calvinianam propvgnantis sævissimvm in Catholicos sui regni Edictvm . . . promulgatum Londini 29 Nouembris 1591. Cum responsione ad singula capita . . . per D. Andream Philopatrum, presb. ac theol. Romanum, Lvgduni, 1592. This Latin work was a detailed rebuttal of a proclamation of Elizabeth I of October 1591, against seminary priests and Jesuits.[16] It was published under the pseudonym Andreas Philopater.[17]

- A Conference abovt the next svccession to the crowne of Ingland, divided into tvvo partes. . . . Where vnto is added a new & perfect arbor or genealogie.... Published by R. Doleman. Imprinted at N. [St. Omer] with licence, 1594. The book suggests Isabella Clara Eugenia of Spain as the proper successor.[18]

- A Memoriall for the Reformation of England conteyning certayne notes and advertisements which seeme might be proposed in the first parliament and nationall councell of our country after God of his mercie shall restore it to the catholique faith [...]; gathered and set downe by R. P., 1596. Left in manuscript, the circulation having included Isabella Clara Eugenia.[3] It was first published in 1690 by Edward Gee, as Jesuits Memorial for the intended Reformation of England.

- A Temperate Ward-word to the turbulent and seditious Wach-word of Sir Francis Hastinges, knight, who indevoreth to slander the whole Catholique cause.... By N. D. 1599. Controversy with Sir Francis Hastings.[19]

- The Copie of a letter written by F. Rob. Persons, the jesuite, 9 Oct 1599, to M. D. Bis[op] and M. Cha[rnock], two banished and consigned priests... for presuming to goe to Rome in the affaires of the Catholicke church. This was printed in Copies of certain Discourses, Roane, 1601, pp. 49–67, edited by William Bishop, one of the appellants in the Archpriest controversy; the other appellant named is Robert Charnock.[20][21]

- A Briefe Apologie or Defence of the Catholike ecclesiastical hierarchie & subordination in England, erected these later yeares by our holy Father ... and impugned by certayne libels printed ... by some vnquiet persons under the name of priests of the seminaries. Written ... by priests vnited in due subordination to the right rev. Archpriest [early in 1602]. Anti-appellant work in the Archpriest controversy.[22]

- An Appendix to the Apologie lately set forth for the defence of the hierarchie [1602]. A Latin translation of the 'Appendix' was also published in the same year.

- A Manifestation of the great folly and bad spirit of certayne in England calling themselves secular priestes, who set forth dayly most infamous and contumelious libels against worthy men of their own religion. By priests liuing in obedience, 1602. Anti-appellant work in the Archpriest controversy.[12]

- The Warn-word to Sir F. Hastings Wastword: conteyning the issue of three former treatises, the Watchword, the Ward-word, and the Wastword . . . Whereunto is adjoyned a brief rejection of an insolent . . . minister masked with the letters O. E. (i.e. Matthew Sutcliffe). By N. D., 1602.

- A Treatise of Three Conversions of England ... divided into three parts. The former two whereof are handled in this book. . . . By N. D., author of the Ward-word, 1603. Polemical work against John Foxe's anti-Catholic reading of history.[23]

- The Third part of a treatise intituled of the Three Conversions of England. Conteyning an examen of the Calendar or Catalogue of Protestant saints . . . devised by Fox. By N. D. (preface dated November 1603).

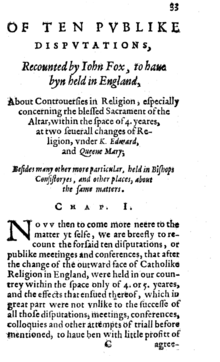

- A Review of ten pvblike dispvtations or conferences held within the compasse of foure yeares vnder K. Edward and Qu. Mary. By N.D., 1604 (separately paged but issued with third part of 'Three Conversions).

- A Relation of the triall made before the king of France upon the yeare 1600 betweene the bishop of Évreux and the L. Plessis Mornay. Newly reviewed . . . with a defence thereof against the impugnations both of the L. Plessis in France and O. E. in England. By N. D., 1604. On the debate at Fontainebleau on 4 May 1600 between Jacques-Davy Duperron and Philippe de Mornay.[24]

- An Ansvvere to the fifth part of Reportes lately set forth by Syr Edward Cooke knight, the King's attorney generall, concerning the ancient and moderne municipal lawes of England, which do appertayne to spiritual power and jurisdiction. By a Catholick Deuyne [St. Omer], 1606. Polemical work against Sir Edward Coke's anti-Catholic reading of the common law.[23]

- Quæstiones duæ: quarum 1a est, an liceat Catholicis Anglicanis . . . Protestantium ecclesias vel preces adire: 2da utrum non si precibus ut concionibus saltem hæreticis . . . licite possint interesse easque audire [St. Omer], 1607. Pope Paul V had repeated the declaration against Catholics attending Protestant churches.[25]

- A treatise tending to mitigation tovvards Catholicke-subiectes in England. . . . Against the seditious wrytings of Thomas Morton, minister. By P. R., 1607 (the first part is on rebellion, the second concerns the doctrine of equivocation). Written in the aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot, the work argues for religious toleration in England.[26]

- The Judgment of a Catholicke Englishman liuing in banishment for his religion . . . concerning a late booke [by K. James] entituled: Triplici nodo triplex cuneus, or an apologie for the oath of allegiance. . . . wherin the said oath is shewn to be vnlawful. . . . 1608. Contribution to the allegiance oath controversy.[27]

- Dutifull and respective considerations upon foure severall heads . . . proposed by the high and mighty Prince James ... in his late book of Premonition to all Christian princes. . . . By a late minister and preacher in England, St. Omer, 1609 (written by Persons for Humphrey Leech, under whose name it appeared). Argues for tolerance for Catholicism in its integrity.[28]

- A quiet and sober reckoning with M. Thomas Morton, somewhat set in choler by his advesary P. R. ... There is also adioyned a peece of reckoning with Syr Edward Cooke, now LL. Chief Justice, 1609. Against Thomas Morton, who had argued that recusant Catholics were necessarily disloyal, Persons argued that Catholicism could co-exist peacefully with the Church of England.[3]

- A Discussion of the answer of M. William Barlow, Doctor of Diuinity, to the book intituled, The Judgment of a Catholic Englishman, St. Omers, 1612 (published after Persons's death, with a supplement by Thomas Fitzherbert). Reply to William Barlow in the allegiance oath controversy.[27]

- Epitome controversiarum hujus temporis was a manuscript preserved in Balliol College.[1]

Misattributed

[edit]An Apologicall Epistle: directed to the right honourable lords and others of her majesties privie counsell. Serving as well for a preface to a Booke entituled A Resolution of Religion [signed R. B.], Antwerp, 1601, is by Richard Broughton rather than Persons (as the Dictionary of National Biography says).[29] Some works against Thomas Bell were thought to be by Persons (as in the DNB), but were in fact by Philip Woodward.[30][31][32]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Lee, Sidney, ed. (1895). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 43. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ a b Pollen, John Hungerford. "Robert Persons." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 25 March 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g Houliston, Victor. "Persons, Robert". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21474. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ McCoog 1996, p. 124 n. 22.

- ^ McCoog 1996, p. 259.

- ^ McCoog, Thomas M. "Pounde, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/69038. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ McCoog 1996, pp. 137–8.

- ^ McCoog 1996, p. 146.

- ^ McCoog 1996, pp. 155–7.

- ^ Brooks, Christopher W. (2009). Law, Politics and Society in Early Modern England. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 121. ISBN 9780521323918.

- ^ Peter Lake; Michael C. Questier (2000). Conformity and Orthodoxy in the English Church: c. 1560 - 1660. Boydell & Brewer. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-85115-797-9. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ a b c Victor Houliston (1 January 2007). Catholic Resistance in Elizabethan England: Robert Persons's Jesuit Polemic, 1580-1610. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7546-5840-5. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ Collected and Edited by John Hungerford Pollen, S.J. (1908), Unpublished Documents Relating to the English Martyrs. Volume I: 1584-1603. Pages 93-95.

- ^ Robert Parsons (1998). Robert Persons S.J.: The Christian Directory (1582): The First Booke of the Christian Exercise, Appertayning to Resolution. BRILL. p. xi. ISBN 978-90-04-11009-0. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ William Thomas Lowndes (1834). The Bibliographer's Manual of English Literature: L - R. Pickering. p. 1227. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Ethelred Luke Taunton, The History of the Jesuits in England, 1580-1773 (1901), p. 148; archive.org.

- ^ Houliston, Victor (1 June 2001). "The Lord Treasurer and the Jesuit: Robert Person's Satirical Responsio to the 1591 Proclamation". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 32 (2): 383–401. doi:10.2307/2671738. ISSN 0361-0160. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ Clark Hulse (2003). Elizabeth I: Ruler and Legend. University of Illinois Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-252-07161-4. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Victor Houliston (1 January 2007). Catholic Resistance in Elizabethan England: Robert Persons's Jesuit Polemic, 1580-1610. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-7546-5840-5. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Thomas Graves Law, A Historical Sketch of the Conflicts between Jesuits and Seculars in the Reign of Queen Elizabeth (1889), p. lxxxvi; archive.org.

- ^ Thomas Graves Law, The Archpriest Controversy vol. 1 (1838), p. 235 note; archive.org.

- ^ Victor Houliston (1 October 2007). Catholic Resistance in Elizabethan England Robert Persons's Jesuit Polemic 1580-1610. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-7546-8668-2. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ a b Victor Houliston (1 January 2007). Catholic Resistance in Elizabethan England: Robert Persons's Jesuit Polemic, 1580-1610. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-7546-5840-5. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Mack P. Holt (1 January 2007). Adaptations of Calvinism in Reformation Europe: Essays in Honour of Brian G. Armstrong. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-7546-8693-4. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Peter Lake; Michael C. Questier (2000). Conformity and Orthodoxy in the English Church: C. 1560 - 1660. Boydell & Brewer. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-85115-797-9. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Roger D. Sell; Anthony W. Johnson (1 April 2013). Writing and Religion in England 1558-1689: Studies in Community-Making and Cultural Memory. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4094-7559-0. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ a b Victor Houliston (1 January 2007). Catholic Resistance in Elizabethan England: Robert Persons's Jesuit Polemic, 1580-1610. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 142–3. ISBN 978-0-7546-5840-5. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Victor Houliston (1 January 2007). Catholic Resistance in Elizabethan England: Robert Persons's Jesuit Polemic, 1580-1610. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-7546-5840-5. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Molly Murray (15 October 2009). The Poetics of Conversion in Early Modern English Literature: Verse and Change from Donne to Dryden. Cambridge University Press. p. 89 note 77. ISBN 978-0-521-11387-8. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Michael C. Questier (13 July 1996). Conversion, Politics and Religion in England, 1580-1625. Cambridge University Press. p. 48 note 42. ISBN 978-0-521-44214-5. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Suellen Mutchow Towers (2003). The control of religious printing in early Stuart England. Boydell Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-85115-939-3. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Frederick Wilse Bateson (1940). The Cambridge bibliography of English literature. 2. 1660-1800. CUP Archive. p. 327. GGKEY:QNELW3AWW36. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

Sources

[edit]- Hogge, Alice (2006). God's Secret Agents: Queen Elizabeth's Forbidden Priests and the Hatching of the Gunpowder Plot. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0007156382.

- Thomas M. McCoog; Campion Hall (University of Oxford) (1996). The Reckoned Expense: Edmund Campion and the Early English Jesuits: Essays in Celebration of the First Centenary of Campion Hall, Oxford (1896-1996). Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-590-6.

- Sullivan, Ceri (1995). Dismembered Rhetoric: English Recusant Writing, 1580 to 1603. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-1611471168.

Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney, ed. (1895). "Parsons, Robert (1546-1610)". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 43. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney, ed. (1895). "Parsons, Robert (1546-1610)". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 43. London: Smith, Elder & Co.