| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for the better regulating of the future Marriages of the Royal Family. |

|---|---|

| Citation | 12 Geo. 3. c. 11 |

| Territorial extent | |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 1 April 1772 |

| Other legislation | |

| Amended by | |

| Repealed by | Succession to the Crown Act 2013[2] |

Status: Repealed | |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

| Revised text of statute as amended | |

The Royal Marriages Act 1772 (12 Geo. 3. c. 11) was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which prescribed the conditions under which members of the British royal family could contract a valid marriage, in order to guard against marriages that could diminish the status of the royal house. The right of veto vested in the sovereign by this Act provoked severe adverse criticism at the time of its passage.[3][4]

It was repealed as a result of the 2011 Perth Agreement, which came into force on 26 March 2015. Under the Succession to the Crown Act 2013, the first six people in the line of succession need permission to marry if they and their descendants are to remain in the line of succession.

Provisions

[edit]The Act said that no descendant of King George II, male or female, other than the issue of princesses who had married or might thereafter marry "into foreign families", could marry without the consent of the reigning monarch, "signified under the great seal and declared in council". That consent was to be set out in the licence and in the register of the marriage, and entered in the books of the Privy Council. Any marriage contracted without the consent of the monarch was to be null and void.

However, any member of the royal family over the age of 25 who had been refused the sovereign's consent could marry one year after giving notice to the Privy Council of an intention so to marry, unless both houses of Parliament expressly declared their disapproval. There was, however, no instance in which the sovereign's consent in Council was formally refused, though there was one where it was sought but the request ignored and others where it was not sought because it was likely to be refused.

The Act further made it a crime to perform or participate in an illegal marriage of any member of the royal family. This provision was repealed by the Criminal Law Act 1967.[5]

Rationale

[edit]The Act was proposed by George III as a direct result of the marriage in 1771 of his brother, Prince Henry, Duke of Cumberland and Strathearn, to the commoner Anne Horton, widow of Christopher Horton and daughter of the first Lord Irnham, MP. Royal assent was given to the Act on 1 April 1772,[6] and it was only on 13 September following that the king learned that another brother, Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh, had in 1766 secretly married Maria, the illegitimate daughter of Sir Edward Walpole and the widow of the 2nd Earl Waldegrave.[7] Both alliances were considered highly unsuitable by the king, who "saw himself as having been forced to marry for purely dynastic reasons".[8]

Couples affected

[edit]

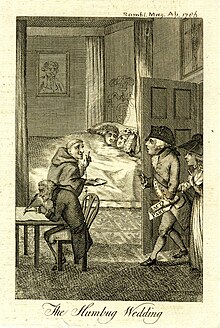

- On 15 December 1785, the King's eldest son George, Prince of Wales, married privately and in contravention of this Act the twice-widowed Maria Anne Fitzherbert, a practising Catholic, at her house in Park Lane, London, according to the rites of the Church of England. This marriage was invalid under the Act. Had the marriage been valid, it would have excluded the Prince from succession to the throne under the terms of the Act of Settlement 1701, and made his brother Prince Frederick, Duke of York, the heir-apparent.

- On 29 September 1791, the King's second son Prince Frederick, Duke of York, married Princess Frederica Charlotte of Prussia, at Charlottenburg, Berlin, but the ceremony had to be repeated in London on 23 November 1791 as, although consent had been given at the Privy Council on 28 September, it had proved impossible to obtain the Great Seal in time and doubt had thus been thrown on the legality of the marriage.[9]

- On 4 April 1793, Prince Augustus, the sixth son of the King, married Lady Augusta Murray, in contravention of the Act, first privately and without witnesses, according to the rites of the Church of England at the Hotel Sarmiento, Rome, and again, after banns, on 5 December 1793, at St George's, Hanover Square, London. Both marriages were declared null and void by the Court of Arches on 14 July 1794, and the two resulting children were subsequently considered illegitimate.[10]

- After the death of Lady Augusta Murray, Prince Augustus, now Duke of Sussex, apparently married (no contemporary evidence survives), again in contravention of the Act, about 2 May 1831, at her house in Great Cumberland Place, London, Lady Cecilia Buggin, who on that day had taken the surname Underwood in lieu of Buggin and who, on 10 April 1840, was created Duchess of Inverness by Queen Victoria (the Duke being Earl of Inverness). The Queen had thereby, as Lord Melbourne wrote, "recognized the moral and religious effect of whatever has taken place whilst she avoided the legal effects of a legal marriage which was what her Majesty was most anxious to do".[11] Acceptance of the marriage would have meant acceptance of the Duke's earlier marriage and the legitimacy of his two children. However, the couple cohabited and were socially accepted as husband and wife.

- On 8 January 1847, the Queen's first cousin Prince George of Cambridge married, by licence of the Faculty Office but in contravention of this Act, Sarah Fairbrother, a pregnant actress with four illegitimate children (two by himself and two by other men), at St James, Clerkenwell. From about 1858, Fairbrother took the name Mrs FitzGeorge. The marriage was invalid, not a morganatic marriage as many have called it.[12] It is also incorrect to say that Queen Victoria refused to consent to this marriage, as no application was made to her under the Act,[13] it being very apparent that no consent would be given.

- After Charles Edward, Duke of Albany was deprived of his British titles under the Titles Deprivation Act 1917 due to his German loyalties during World War I, his descendants married without consent from the British monarch (the earliest in 1932[citation needed]). As Charles Edward was a male-line grandson of Queen Victoria, application of the Royal Marriages Act as written renders null and void for the purposes of British law the marriages of his children, despite having been lawfully contracted in Germany.[a]

- The only known case in which permission to marry was withheld by the British sovereign despite a formal request under the Royal Marriages Act is that of Prince George William of Hanover, a German citizen descended from King George III, whose father and grandfather were deprived of their British titles under the Titles Deprivation Act 1917 due to their German loyalties during World War I. On 23 April 1946, George William married Princess Sophie of Greece and Denmark, who was about to become a kinswoman to the British royal family as her brother Prince Philip was courting the future Queen Elizabeth II. Their request for permission from King George VI received no response due to sensitivity over the fact that a state of war still existed between the United Kingdom and Germany,[b] and it was held by British officials at the time that the marriage and its issue would not be legitimate in the United Kingdom despite being legal in Germany.[14]

Broad effects

[edit]The Act rendered void any marriage wherever contracted or solemnised in contravention of it. A member of the royal family who contracted a marriage that violated the Act did not thereby lose his or her place in the line of succession,[8] but the offspring of such a union were made illegitimate by the voiding of the marriage and thus lost any right to succeed.

The Act applied to Catholics, even though they are ineligible to succeed to the throne.[8] It did not apply to descendants of Sophia of Hanover who are not also descendants of George II, even though they are still eligible to succeed to the throne.

It had been claimed that the marriage of Prince Augustus had been legal in Ireland and Hanover, but the Committee of Privileges of the House of Lords ruled (in the Sussex Peerage Case, 9 July 1844) that the Act incapacitated the descendants of George II from contracting a legal marriage without the consent of the Crown, either within the British dominions or elsewhere.

All European monarchies, and many non-European realms, have laws or traditions requiring prior approval of the monarch for members of the reigning dynasty to marry. But Britain's was unusual because it was never modified between its original enactment and its repeal 243 years later, so that its ambit grew rather wide, affecting not only the British royal family, but more distant relatives of the monarch.

Farran exemption

[edit]In the 1950s, Charles d'Olivier Farran, Lecturer in Constitutional Law at Liverpool University, theorised that the Act could no longer apply to anyone living, because all the members of the immediate royal family were descended from British princesses who had married into foreign families. The loophole is due to the Act's wording, whereby if a person is, through one line, a descendant of George II subject to the Act's restriction, but is also, separately through another line, a descendant of a British princess married into a foreign family, the exemption for the latter reads as if it trumps the former.[16]

Many of George II's descendants in female lines have married back into the British royal family. In particular, Queen Elizabeth II and other members of the House of Windsor descend through Queen Alexandra from two daughters of King George II, Princesses Mary and Louise, who married foreign rulers, respectively Landgrave Frederick II of Hesse-Kassel and King Frederick V of Denmark, and through Queen Mary from a third, Princess Anne, who married Prince William IV of Orange. Queen Mary herself was a product of such a marriage; her parents were Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge, a granddaughter of George III and Francis, Duke of Teck, a minor German prince of the House of Württemberg. Moreover, King Charles III, his issue, siblings, and their issue descend from yet another such marriage, that of Princess Alice, a daughter of Queen Victoria, to Grand Duke Louis IV of Hesse, through their great-grandson Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

This so-called "Farran exemption" met with wide publicity, but arguments against it were put forward by Clive Parry, Fellow of Downing College, Cambridge,[17] and Farran's interpretation has since been ignored.[18] Consent to marriages in the royal family (including the distantly related House of Hanover) continued to be sought and granted as if none of the agnatic descendants of George II were also his cognatic descendants.

Parry argued that the "Farran exemption" theory was complicated by the fact that all the Protestant descendants of the Electress Sophia of Hanover, ancestress of the United Kingdom's monarchs since 1714, had been entitled to British citizenship under the Sophia Naturalization Act 1705 (if born prior to 1949, when the act was repealed). Thus, some marriages of British princesses to continental monarchs and princes were not, in law, marriages to foreigners. For example, the 1947 marriage of Princess Elizabeth to Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, by birth a Greek and Danish prince but descended from the Electress Sophia, was a marriage to a British subject even if he had not been previously naturalised in Britain. This would also mean theoretically, for example, that the present royal family of Norway was bound by the Act, for the marriage of Princess Maud, a daughter of King Edward VII, to the future King Haakon VII of Norway, was a marriage to a "British subject", since Haakon descended from the Electress Sophia.

Exemption of the former Edward VIII

[edit]In 1936 the statute His Majesty's Declaration of Abdication Act 1936 specifically excluded Edward VIII from the provisions of this Act upon his abdication, allowing him to marry the divorcée, Wallis Simpson. The wording of the statute also excluded any issue of the marriage both from being subject to the Act, and from the succession to the throne; no marriages or succession rights were ultimately affected by this language, as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor had no children.[19]

Perth Agreement

[edit]In October 2011 David Cameron wrote to the leaders of the other Commonwealth realms proposing that the Act be limited to the first six people in line to the throne.[20] The leaders approved the proposed change at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting held in Perth, Western Australia.[21]

The legislation in a number of Commonwealth realms repeals the Royal Marriages Act 1772 in its entirety. It was, in the United Kingdom, replaced by the Succession to the Crown Act 2013, which stipulates a requirement for the first six people in the line of succession to obtain the sovereign's consent before marrying in order to remain eligible. Article 3(5) of the new Act also provides that, except for succession purposes, any marriage that would have been void under the original Act "is to be treated as never having been void" if it did not involve any of the first six people in the line of succession at the time of the marriage; royal consent was never sought or denied; "in all the circumstances it was reasonable for the person concerned not to have been aware at the time of the marriage that the Act applied to it"; and no one has acted on the basis that the marriage is void. New Zealand's Royal Succession Act 2013 repealed the Royal Marriages Act and provided for royal consent for the first six people in the line of succession to be granted by the monarch in right of the United Kingdom.[22]

Other legislation

[edit]The Regency Act 1830, which provided for a regency in the event that Queen Victoria inherited the throne before she was eighteen, made it illegal for her to marry without the regent's consent. Her spouse and anyone involved in arranging or conducting the marriage without such consent would be guilty of high treason. This was more serious than the offence created by the Act of 1772, which was equivalent to praemunire. However, the Act never came into force, as Victoria had already turned 18 a few weeks before becoming queen.

Consents for marriages under the Act

[edit]Consents under the Act were entered in the Books of the Privy Council but have not been published. In 1857 it became customary to publish them in the London Gazette and notices appear of consents given in Council at Courts held on the following dates. Not all consents were there and gaps in the list have been filled by reference to the Warrants for Royal Marriages in the Home Office papers (series HO 124) in The National Archives:[23]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ According to a Home Office memorandum on the matter, "All the descendants of a British prince require the consent, even if he has become a foreign Sovereign and his family have lived abroad for generations. Thus the Hanoverian Royal Family, who are descended from George III's son, the Duke of Cumberland, who succeeded to the throne of Hanover on the accession of Queen Victoria, have regularly obtained the King's consent to their marriages: in 1937 Princess Frederica of Hanover, great-great granddaughter of George III and 3rd cousin once removed of the King, asked his consent to her wedding with the Crown Prince of Greece. It seems absurd that the King's consent should be obtained for a purely foreign marriage of this kind; one can only suppose that as the marriage would not be valid in the British Dominions without it, the object is to secure the position of the issue as Princes or Princesses of Great Britain (which rank is much valued on the Continent) and possibly to retain their place in the line of succession to the British Throne. Obviously the absence of the Royal Consent required by British law could not affect the validity of a marriage contracted abroad so far as the law of the country of domicile of the parties is concerned. It should be noted here that the Act applies to all marriages in which one of the parties is a descendant of George II, whether contracted in Great Britain or abroad. See as to this the decision of the House of Lords, given after taking the opinion of the Judges, in the Sussex Peerage case (xi Clark and Finelly, 85 ff.)"[14]

- ^ After consultations with the Foreign Office, Home Office and King George VI's private secretary, Sir Alan Lascelles, a ciphered telegram dated 18 April 1946 and crafted by Sir Albert Napier, permanent secretary to the Lord Chancellor, was transmitted from the British Foreign Office to the Foreign Adviser to the British Commander in Chief at Berlin: "The Duke of Brunswick has formally applied to The King by letter of March 22nd for the consent of His Majesty under the Act 12 Geo. III, cap. 11 to the marriage of his son Prince George William with Princess Sophia Dowager Princess of Hesse. The marriage is understood to be taking place on April 23rd. Please convey to the Duke an informal intimation that in view of the fact that a state of war still exists between Great Britain and Germany, His Majesty is advised that the case is not one in which it is practicable for His consent to be given in the manner contemplated by the Act."[15]

References

[edit]- ^ The citation of this Act by this short title was authorised by the Short Titles Act 1896, section 1 and the first schedule. Due to the repeal of those provisions it is now authorised by section 19(2) of the Interpretation Act 1978.

- ^ "Section 3 – Succession to the Crown Act 2013". Legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ C. Grant Robertson, Select statutes, cases and documents to illustrate English constitutional history (4th edn. 1923) pp. 245–247

- ^ Lord Mackay of Clashfern, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, ed. Halsbury's Laws of England (4th edn. 1998), volume 21 (1), p. 21

- ^ Criminal Law Act 1967, Section 13 and Schedule 4.

- ^ "No. 11236". The London Gazette. 4 April 1772. p. 1.

- ^ Matthew Kilburn, William Henry, Prince, first duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh (1743–1805), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2011

- ^ a b c Bogdanor, Vernon (1997). The Monarchy and the Constitution. Oxford University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-19-829334-7.

- ^ A. Aspinall, ed., The later correspondence of George III, vol. 1 (1966) pp. 567–671. The statement in Michel Huberty, Alain Giraud, F. and B. Magdelaine, L'Allemagne Dynastique, vol. 3: Brunswick-Nassau-Schwarzbourg (1981) p. 146, that the first marriage was by procuration (or proxy) is incorrect.

- ^ This marriage, being invalid, was not morganatic as is frequently stated, e.g. by Michael Thornton, Royal Feud (1985) p. 161.

- ^ Mollie Gillen, Royal Duke (1976) p. 223.

- ^ e.g. Compton Mackenzie, The Windsor tapestry (1938) page 344; Michael Thornton, Royal Feud (1985) pp. 161–162, and many other authorities.

- ^ As stated in Brian Inglis, Abdication (1966) p. 265, and many other authorities.

- ^ a b Eagleston, Arthur J. The Home Office and the Crown. pp. 9–14. The National Archives (UK)|TNA, HO 45/25238, Royal Marriages.

- ^ Marriage of Prince George William, son of the Duke of Brunswick, with Princess Sophia, Dowager Princess of Hesse. Request for The King's consent. The National Archives (UK) LCO 2/3371A.

- ^ Modern Law Review, volume 14 (1951) pp. 53–63;

- ^ in 'Further Considerations on the Prince of Hanover's Case' in International & Comparative Law Quarterly (1957) pp. 61 etc.

- ^ Farran replied to Mr Parry in Appendix I, 'The Royal Marriages Act Today', in Lucille Iremonger, Love and the Princesses (1958) pp. 275–280.

- ^ His Majesty's Declaration of Abdication Act 1936 (c.3), full text online at statutelaw.gov.uk

- ^ "David Cameron proposes changes to royal succession". BBC News. 12 October 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ "Girls equal in British throne succession". BBC News. 28 October 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ "Certain people excluded from succession to the Crown on marrying without consent of Sovereign". Royal Succession Act 2013 (Public Act No. 149). New Zealand. 17 December 2013. s 8. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ "Discovery". The National Archives. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ Email from the Privy Council Office dated 11 January 2013: "We do not have any record available as to the omission of the consent in the London Gazette, but I can confirm that consent was given by Her Majesty in Council on 27th March 1981."