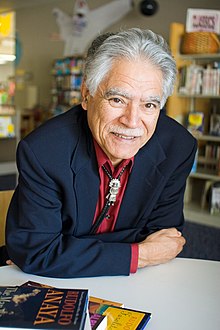

Rudolfo Anaya | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 30, 1937 Pastura, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Died | June 28, 2020 (aged 82) Albuquerque, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | American |

| Notable works | Bless Me, Ultima Alburquerque |

| Notable awards | |

| Spouse | Patricia Lawless |

Rudolfo Anaya (October 30, 1937 – June 28, 2020) was an American author. Noted for his 1972 novel Bless Me, Ultima, Anaya was considered one of the founders of the canon of contemporary Chicano and New Mexican literature.[1][2] The themes and cultural references of the novel, which were uncommon at the time of its publication, had a lasting impression on fellow Latino writers. It was subsequently adapted into a film and an opera.

Early life and education

[edit]Rudolfo Anaya was raised in Santa Rosa, New Mexico. His father, Martín Anaya, was a vaquero from a family of cattle workers and sheepherders. His mother, Rafaelita (Mares), was from a family composed of farmers from Puerto De Luna in the Pecos Valley of New Mexico.[3] Anaya grew up with two half-brothers, from his mother's previous marriage, and four sisters. The beauty of the desert flatlands of New Mexico, referenced as the llano in Anaya's writings, had a profound influence on his early childhood.[4]

Anaya's family relocated from rural New Mexico to Albuquerque in 1952, when he was in the eighth grade.[5] He attended Albuquerque High School, graduating in 1956.[4] This experience later appeared as an autobiographical allusion in his novel Tortuga.[3] When he was 16 he sustained a spinal cord injury which left him temporarily paralyzed.[6] Following high school, he earned a B.A. in English and American Literature from the University of New Mexico in 1963. He went on to complete two master's degrees at the University of New Mexico, one in 1968 for English and another in 1972 for guidance and counseling.[3] While earning his master's degrees, Anaya worked as a high school English teacher in the Albuquerque public schools from 1963 until 1968.[4][7] In 1966, he married Patricia Lawless, who continued to support his writing.[3]

Career

[edit]He began writing his best-known work Bless Me, Ultima in 1963, with the manuscript completed and published by Quinto Sol in 1972.[3] Initially, Anaya faced tremendous difficulty getting his work published by mainstream publishing houses because of its unique combination of English and Spanish language, as well as its Chicano-centric content.[8] Independent publishing house Quinto Sol quickly published the book after awarding it the Premio Quinto Sol in 1971 for best novel written by a Chicano.[3] The book went on to sell over 300,000 copies in 21 printings.[9] The themes and cultural references touched on in the novel were uncommon at the time of its publication. Consequently, it ended up having a lasting impact on a generation of Latino writers.[10]

Following the book's success, Anaya was invited to join the English faculty at the University of New Mexico in 1975, where he taught until his retirement in 1993.[8]

Anaya traveled extensively through both China in 1984, and South America following his retirement. His experiences in China are chronicled in his travel journal, A Chicano in China, published in 1986.[3][4]

During the 1990s, Anaya found an even wider audience as mainstream publishing house Warner books signed him on for a six-book deal beginning with the novel Alburquerque. He subsequently created the Sonny Baca mystery series which included Zia Summer, Rio Grande Fall, Jalamanta: A Message from the Desert, and Shaman Winter. The Anaya Reader, a collection of his works, followed.[4][9][11]

Bless Me, Ultima was released as a feature film on February 22, 2013.[12] It was subsequently adapted into an opera three years later.[13] Anaya also published a number of books for children and young adults. His first children's book was The Farolitos of Christmas, published in 1995.[4]

Anaya's non-fiction work has appeared in many anthologies. In 2015, 52 of his collected essays exploring identity, literature, immigration, and politics were published as The Essays with Open Road Media.[14] In summarizing his career, Anaya stated "What I’ve wanted to do is compose the Chicano worldview—the synthesis that shows our true mestizo identity—and clarify it for my community and for myself."[15]

Anaya lived in Albuquerque, where each day he spent several hours writing.[4][16] He died at his home on June 28, 2020, at the age of 82.[17][18] He had been suffering from a long illness in the time leading up to his death.[10]

Bibliography

[edit]Fiction

[edit]- Bless Me, Ultima (1972), ISBN 0-446-67536-9

- Heart of Aztlan (1976), ISBN 0-915808-18-8

- Tortuga (1979), ISBN 0-915808-34-X

- Silence of the Llano: Short Stories (1982), ISBN 0-89229-009-9

- The Legend of La Llorona: A Short Novel (1984), ISBN 0-89229-015-3

- Lord of the Dawn: the Legend of Quetzalcóatl (1987), ISBN 0-8263-1001-X

- Alburquerque (1992), ISBN 0-8263-1359-0[19]

- Jalamanta: A Message from the Desert (1996), ISBN 0-446-52024-1

- Serafina's Stories (2004), ISBN 0-8263-3569-1

- The Man Who Could Fly and Other Stories (2006), ISBN 0-8061-3738-X

- Randy Lopez Goes Home: A Novel (Chicana & Chicano Visions of the Americas Series) (2011), ISBN 0806141891

- The Old Man's Love Story (Chicana & Chicano Visions of the Americas series) (2013), ISBN 0806143576

- The Sorrows of Young Alfonso (Chicana & Chicano Visions of the Americas series) (2016), ISBN 978-0806152264

Sonny Baca series

[edit]The occult detective fiction series following the titular character Sonny Baca.

- Zia Summer (1995), ISBN 0-446-51843-3

- Rio Grande Fall (1996), ISBN 0-446-51844-1

- Shaman Winter (1999), ISBN 0-446-52374-7

- Jemez Spring (2005), ISBN 0-8263-3684-1

Books for children

[edit]- The Farolitos of Christmas: A New Mexico Christmas Story (1987), ISBN 0-937206-05-9

- Maya's Children: The Story of La Llorona (1996), illustrated by Maria Baca, ISBN 0-7868-0152-2

- Farolitos for Abuelo (1998), illustrated by Edward Gonzalez, ISBN 0-7868-0237-5

- My Land Sings: Stories from the Rio Grande (1999), illustrated by Amy Córdova, ISBN 0-688-15078-0

- Elegy on the Death of César Chávez (2000), illustrated by Gaspar Enriquez, ISBN 0-938317-51-2

- Roadrunner's Dance (2000), illustrated by David Diaz, ISBN 0-7868-0254-5

- The Santero's Miracle: A Bilingual Story (2004), illustrated by Amy Córdova, Spanish translation by Enrique Lamadrid, ISBN 0-8263-2847-4

- The Curse of the ChupaCabra (2006), ISBN 0-8263-4114-4

- The First Tortilla (2007), illustrated by Amy Córdova, Spanish translation by Enrique Lamadrid, ISBN 0-8263-4214-0

- ChupaCabra and the Roswell UFO (2008), ISBN 0-8263-4469-0

Non-fiction and anthologies

[edit]- Voices from the Rio Grande: Selections from the First Rio Grande Writers Conference (1976)

- Cuentos: Tales from the Hispanic Southwest (1980), with Jose Griego y Maestas, ISBN 0-89013-111-2

- A Ceremony of Brotherhood, 1680–1980 (1981), edited with Simon J. Ortiz

- Cuentos Chicanos: A Short Story Anthology (rev. ed. 1984), edited with Antonio Márquez, ISBN 0-8263-0772-8

- A Chicano in China (1986), ISBN 0-8263-0888-0

- Voces: An Anthology of Nuevo Mexicano Writers (1987, 1988), editor, ISBN 0-8263-1040-0

- Aztlán: Essays on the Chicano Homeland (1989), edited with Francisco A. Lomelí, ISBN 0-929820-01-0

- Tierra: Contemporary Short Fiction of New Mexico (1989), editor, ISBN 0-938317-09-1

- Flow of the River (2nd ed. 1992), ISBN 0-944725-00-7

- Descansos: An Interrupted Journey (1995), with Denise Chávez and Juan Estevan Arellano, ISBN 0-929820-06-1

- Muy Macho: Latino Men Confront Their Manhood, edited and introduction by Ray Gonzales, ISBN 0-385-47861-5

- Chicano/a Studies: Writing into the Future (1998), edited with Robert Con Davis-Undiano

Poetry

[edit]- Adventures of Juan Chicaspatas (1985), ISBN 0-934770-45-X

Published or performed plays

[edit]- The Season of La Llorona[20]

- Ay, Compadre! (1994)[20]

- The Farolitos of Christmas (1987)[20]

- Matachines (1992)[20]

- Billy the Kid (1995)[20]

- Who Killed Don Jose? (1995)[20]

- Rosa Linda (2013)[21]

- Bless Me, Ultima (2018)[13]

Bibliographical Resources

[edit]- works and editions: https://faculty.ucmerced.edu/mmartin-rodriguez/index_files/vhAnayaRudolfo.htm

Musical adaptations

[edit]- "La Llorona" (2002) an opera based on his play The Seasons of La Llorona. Libretto by Rudolfo Anaya. Composer, Daniel Steven Crafts Premiere 2008 National Hispanic Cultural Center

- "Cancion al Rio Grande" (2007) an orchestral setting of his poem of the same name, written for inclusion into the work for tenor and orchestra, From a Distant Mesa composed by Daniel Steven Crafts. Premiere 2012, New Mexico Philharmonic.

Awards and honors

[edit]Source:[22]

- Premio Quinto Sol literary award, for Bless Me, Ultima, 1970

- NM Governor's Public Service Award, 1978, 1980

- Natl Chicano Council on Higher Education fellowship, 1978–79

- NEA fellowships, 1979, 1980

- American Book Award, Before Columbus Foundation, for Tortuga, 1980

- D.H.L., Univ. of Albuquerque, 1981

- Corporation for Public Broadcasting script development award, for "Rosa Linda," 1982

- Award for Achievement in Chicano Literature, Hispanic Caucus of Teachers of English, 1983

- Kellogg Foundation fellowship, 1983–85

- D.H.L., Marycrest Coll., 1984

- Mexican Medal of Friendship, Mexican Consulate of Albuquerque, 1986

- PEN-West Fiction Award, 1992, for Alburquerque[14][23]

- NEA National Medal of Arts Lifetime Honor, 2001[24][25]

- Outstanding Latino/a Cultural Award in Literary Arts or Publications, American Association of Hispanics in Higher Education (AAHHE), 2003

- People's Choice Award, 2007 New Mexico Book Awards[26]

- Notable New Mexican 2007[27]

- Robert Kirsch Award 2011[28]

- Lifetime Achievement Award in Literature from the Paul Bartlett Re Peace Prize, 2014[29][30]

- Inducted into Albuquerque's Wall of Fame, 2014[31]

- 2015 National Humanities Medal[32]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cesar A. Gonzales-T., The Ritual and Myth of Experience in the Works of Rudolfo A. Anaya, published in A Sense of Place: Rudolfo A. Anaya: An Annotated Bio-Bibliography (2000).

- ^ Garcia, Annemarie Lynette (2010). A culture of divisions : cultural representations of La Bruja and La Curandera in Nuevo Mexicano folklore and literature. OCLC 727743507.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fernandez Olmos, Margarite. "The Life of Rudolfo A. Anaya." Rudolfo A. Anaya: A Critical Companion. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 1999. ABC-CLIO eBook Collection. Web. February 20, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Gale – Free Resources – Hispanic Heritage – Biographies – Rudolfo Anaya". Archived from the original on January 7, 2008. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ Con Davis-Undiano, Robert. "Author profile: Rudolfo A. Anaya." World Literature Today 79.3–4 (2005): 88. Academic OneFile. Web. 20 Feb. 2013.

- ^ Romero, Simon (July 3, 2020). "Rudolfo Anaya, a Father of Chicano Literature, Dies at 82". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ^ Anaya, R.A.; Dick, B.; Sirias, S. (1998). Conversations with Rudolfo Anaya. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781578060788. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ a b Clark, William. "Rudolfo Anaya: 'the Chicano worldview.'(Interview)." Publishers Weekly, June 5, 1995: 41+. Academic OneFile. Web. February 20, 2013.

- ^ a b Clark, William. "The mainstream discovers Rudolfo Anaya." Publishers Weekly, March 21, 1994: 24. Academic OneFile. Web. February 20, 2013.

- ^ a b "Rudolfo Anaya, 'godfather' of Chicano literature, dies at 82". Associated Press. July 1, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "'Bless Me, Ultima,' a New Mexico classic of Chicano literature". Taos News. November 21, 2018.

- ^ "Bless Me, Ultima The Movie". blessmeultima.com. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ a b Zavoral, Linda (April 18, 2018). "Opera Cultura to present classic 'Bless Me, Ultima'". The Mercury News. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Anaya, Rudolfo (November 24, 2015). The Essays. Open Road Media. ISBN 9781480442856.

- ^ Smith, Harrison (July 1, 2020). "Rudolfo Anaya, novelist who helped launch Chicano literary movement, dies at 82". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Library renamed in author Rudolfo Anaya's honor". KOB4. March 15, 2018.

- ^ "Beloved NM author Rudolfo Anaya passes away". June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Famed Chicano author Rudolfo Anaya dies at age 82". June 30, 2020.

- ^ Anaya, Rudolfo (January 2, 2024). Alburquerque: A Novel: Rudolfo Anaya: 9780826340597: Amazon.com: Books. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0826340597.

- ^ a b c d e f Fernández Olmos, Margarite (1999). Rudolfo A. Anaya: A Critical Companion. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 151. ISBN 9780313306419.

- ^ Olmstead, Donna (April 14, 2013). "Anaya play looks at life in old N.M." Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Gale – Free Resources – Hispanic Heritage – Biographies – Rudolfo Anaya". Archived from the original on January 7, 2008. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- ^ "Rudolfo Anaya Digital Archive Fund". University of New Mexico Foundation. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Rudolfo Anaya". National Endowment for the Arts. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Lifetime Honors – National Medal of Arts". National Endowment for the Arts. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "New Mexico Book Awards – Winners & Finalists". New Mexico Book Co-op. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "The Notable New Mexican Program". Albuquerque Museum Foundation. Archived from the original on January 1, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "2011 Los Angeles Times Book Prize Winners". Los Angeles Times. April 20, 2012. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "2014 Paul Ré Peace Prize Winners Selected for Outstanding Peace Promotion Activities". University of New Mexico Foundation. June 11, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "The Paul Bartlett Ré Peace Prize". The Paul Ré Archives. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Bush, Mike (September 29, 2014). "ABQ Wall of Fame's newest member is Rudolfo Anaya". Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "President Obama to Award 2015 National Humanities Medals". National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). Retrieved September 12, 2020.

External links

[edit]- Western American Literature Journal: Rudolfo Anaya

- Rudolfo A. Anaya Papers (MSS 321), Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections, University of New Mexico Libraries.

- "Bless Me, Ultima" Official Trailer (2013)