| Sabana Formation | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Mid to Late Pleistocene (Ensenadan-Lujanian) ~ | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Underlies | Holocene unconsolidated sediments |

| Overlies | Subachoque Fm., Tilatá Fm. |

| Area | ~4,500 km2 (1,700 sq mi) |

| Thickness | up to 320 m (1,050 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Shale |

| Other | Lignite, sandstone, volcanic ash |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 4°43′02.3″N 74°13′01.2″W / 4.717306°N 74.217000°W |

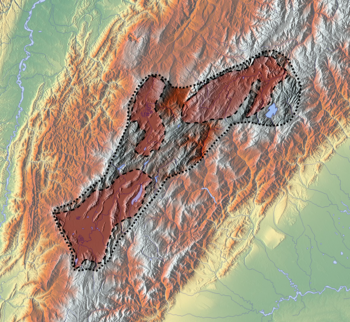

| Region | Bogotá savanna, Altiplano Cundiboyacense Eastern Ranges, Andes |

| Country | |

| Extent | ~90 km × 40 km (56 mi × 25 mi) |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Bogotá savanna |

| Named by | Helmens & Hammen |

| Location | Funza II well |

| Year defined | 1995 |

| Coordinates | 4°43′02.3″N 74°13′01.2″W / 4.717306°N 74.217000°W |

| Region | Cundinamarca |

| Country | |

| Thickness at type section | 317 m (1,040 ft) |

Paleogeography of the Pleistocene by Ron Blakey | |

The Sabana Formation (Spanish: Formación Sabana, Q1sa, QTs) is a geological formation of the Bogotá savanna, Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes. The formation consists mainly of shales with at the edges of the Bogotá savanna lignites and sandstones. The Sabana Formation dates to the Quaternary period; Middle to Late Pleistocene epoch, and has a maximum thickness of 320 metres (1,050 ft), varying greatly across the savanna. It is the uppermost formation of the lacustrine and fluvio-glacial sediments of paleolake Humboldt, that existed at the edge of the Eastern Hills until the latest Pleistocene.

The uppermost sediments of the Sabana Formation were deposited during the Last Glacial Maximum, a time when the first humans populated the Bogotá savanna. These hunter-gatherers used the bones of the still extant Pleistocene megafauna as Notiomastodon platensis, Cuvieronius hyodon and Equus neogeus, of which fossils have been found in the Sabana Formation.

Knowledge about the formation has been provided by geologists Alberto Guerrero, Thomas van der Hammen and others.

Etymology

[edit]The formation was first defined and named after the Bogotá savanna (Sabana de Bogotá) by Hubach in 1957, further described by Van der Hammen in 1973,[1] Guerrero (1992, 1993, 1996) and by Helmens and Van der Hammen in 1995.[2][3][4][5]

Regional setting

[edit]The Bogotá savanna is a slightly undulated montane savanna in the southwestern part of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, a high plateau in the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes. The Altiplano was formed during the latest stage of Andean uplift in the Plio-Pleistocene, exposing rocks of mainly Cretaceous to Paleogene ages at surface. A small massif of Paleozoic age is present in the northern part of the Altiplano; the Floresta Massif around Floresta comprising the fossiliferous formations Floresta and Cuche.

During the Mesozoic, the central part of Colombia was a rift basin to the west of the Guyana Shield, where series of marine platform deposits were deposited. The proto-Caribbean, the result of the break-up of Pangea, formed a long seaway into the South American Plate, up to Bolivia. During the Late Cretaceous, the Western and Central Ranges of the Colombian Andes began rising, while the Eastern Ranges was still absent. The main phase of tectonic uplift of the Eastern Ranges commenced in the Middle Miocene, marked by a change in paleocurrents of the fluvial deposits of the Honda Group, the most fossiliferous stratigraphic unit of Colombia.

Subduction of the Nazca Plate underneath western South America and the resulting compression in the continent created reversal of former extensional faults of the Mesozoic rift basin in the Eastern Ranges. A series of fold and thrust belts, oriented in a north–south to northeast–southwest sense, were formed in the Eastern Andes, uplifting the former marine strata and creating a high plateau between the western and eastern fronts; the Altiplano Cundiboyacense. The tectonic movements of this Andean orogenic phase are reflected in Upper Miocene units as the Marichuela Formation, underlying the Pliocene and Pleistocene sediments of which the Sabana Formation represents the final chapter.

Description

[edit]

Lithologies

[edit]The Sabana Formation consists mainly of horizontally bedded little consolidated grey and greenish shales with lignite and diatomites,[3] and fine to coarse sandstones at the edges of the Bogotá savanna.[6] Numerous volcanic ash deposits are noted in the Sabana Formation.[2] Organic material is preserved in black soils and silts form the terraces of the central part of the savanna.[5] The volcanic ash had as provenance area the Central Ranges of the Colombian Andes, with probably minor influences from the volcanic areas of Boyacá (Paipa–Iza volcanic complex). The diatomites are associated with the ash layers, a common feature in the geological record.[7]

Stratigraphy

[edit]The Sabana Formation in some areas conformably overlies the Subachoque Formation, in other parts unconformably the Tilatá Formation, and is overlain by the alluvium of the Holocene, with the southeasternmost area of the savanna covered and intercalated by the fluvio-glacial deposits of the Tunjuelo Formation.[3] The formation is subdivided into six units of alternating shales and fine sandstones. The age has been estimated to be Middle to Late Pleistocene, based on fission track analysis and radiocarbon dating. The Sabana Formation is time equivalent with the Soatá (upper Sabana),[8] and Sogamoso Formations of the northern Altiplano,[9] and the upper part of the Guayabo Formation of the Llanos Basin.[4]

Depositional environment

[edit]

The depositional environment has been interpreted as lacustrine (Lake Humboldt) and fluvio-deltaic,[2] with a near-continuous deposition since the Late Pliocene. The Sabana Formation represents the uppermost unit of the lacustrine deposition of Lake Humboldt.[5] At the edges of the lake, numerous deltas of fluvio-glacial origin were present, reflected in the coarser sediments. During periods of stormy climate around the lake, coarser sediments were transported to the interior of the lake. The depositional cycles were geologically speaking fast and the water level of the lake fluctuated greatly during its history. Furthermore, the local tectonic activity of the Bogotá savanna, related to movements of the Bogotá Fault, influenced the depositional cycles. The middle unit of the formation shows a drying out of the lake and subaerial erosional surfaces.[10] The upper part of the Sabana sequence is characterised by fluvial deposits around a retreating Lake Humboldt, estimated at an age of around 30,000 years BP. The glacial origin was predominantly the Sumapaz Páramo to the south of the Bogotá savanna, with minor snow-capped peaks in the Eastern Hills of Bogotá.[11]

Present-day, the lakes of Fúquene, Herrera and Suesca are remnants of Lake Humboldt, as well as the many wetlands of Bogotá.[6]

Paleoecology

[edit]The Sabana Formation was deposited during the Pleistocene glaciations and interglacials ("ice ages"). The fluctuations in climate in the Eastern Colombian Andes have been studied around Lake Fúquene at an altitude of 2,540 metres (8,330 ft), to the north of the Bogotá savanna. During the Last Glacial Maximum of the Pleistocene, the paleoecology of the region varied drastically, marking movements of the upper tree line and the types of vegetation. Pollen analysis shows that páramo vegetation was abundant from 30 ka to 17,500 years ago, with an increase in Andean forest frequency dated at 15.6 ka. Between 13,000 and 11,000 years BP, a decrease in Andean forest percentage is observed, indicative of a colder climate than before. This period has been named the Fúquene stadial. The stadial is followed by an interstadial (Guantivá), with an increase in lake levels of Lake Fúquene.[12] The wetter periods of the interstadial covered earlier paleotopography with humic sediments.[13]

During the last phase of deposition of the Sabana Formation, the Bogotá savanna was surrounded by populations of Pleistocene megafauna. Fossils of the ground sloths Megatherium and Eremotherium have been uncovered from Quipile,[14][15] and Fusagasugá and Tocaima respectively, Notiomastodon platensis from Tocaima and Pubenza, accompanied by shells of Neocyclotus cf. cingulatus,[16] to the west of the savanna, and Cuvieronius hyodon and Equus neogeus from the Sabana Formation at Tibitó.[17][18] The migration of fauna was favoured by the existence of a dry corridor from the Magdalena River to the Eastern Ranges.[19] Analysis of the fluorine in a fossil molar of a gomphothere, found in the Sabana Formation at Mosquera, provided an age between the last interglacial and the first stage of the last glacial of the Last Glacial Maximum.[20] The fossils of Pubenza and Tibitó were dated at 16,300 ± 150 and 11,740 ± 110 years BP respectively.[16] Researchers at the Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, UNIRIO propose that all gomphotheres found in Colombia should be reassigned to a single species; Notiomastodon platensis.[21][22][23][24] At the latest age of Tibitó, a páramo ecosystem was dominant.[25]

Human settlement

[edit]The location of the capital of the New Kingdom of Granada (Santafe de) Bogotá is different from its namesake, Bacatá

The latest sedimentation phase of the Sabana Formation, evidenced by the sites El Abra, Tibitó and Tequendama, was accompanied by the first confirmed human settlement in Colombia. Around 12,500 years BP, groups of hunter-gatherers populated the rock shelters surrounding the retreating Lake Humboldt. The people of the area hunted the still extant Pleistocene species, and used their remains for the construction of primitive settlements, as bone tools and the skins as clothing. At this stage, the timber line was 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) lower than today.[26]

During the Holocene, the inhabitants of the Bogotá savanna gradually moved away from the rock shelters as permanent settlements in favour of more open area locations, as Checua and Aguazuque. Around 5000 years BP, agriculture became a more dominant phenomenon and the fertile clays mixed with volcanic ash of the Sabana Formation, combined with the bimodal pattern of seasonal precipitation made the Bogotá savanna an ideal area for growing crops. Pottery was used in the Herrera Period, from around 2800 years BP onwards, and the sediments of the Sabana Formation were used for various styles of ceramics, grouped by researchers based on the colour of the original clays. The northern settlement of Suesca was an important ceramic producing centre for the people. An advanced civilisation developed in the first and second millennia CE, leading to the Muisca Confederation, a loose collection of caciques. The southern Muisca area was centered around the Bogotá savanna with as main settlement Bacatá in the middle of the savanna, the namesake of the current capital of Colombia, Bogotá.[27]

With the expansion in the late colonial and early republican era of the Colombian capital to the west and north of the city, the unconsolidated finer sediments of the Sabana Formation became more and more the foundation for construction, leading to problems due to the differential compaction of the sandy and more clay-rich strata.[28]

Outcrops

[edit]The Sabana Formation is found at its type locality in the Funza II well, and covering most of the Bogotá savanna.[2] The newer parts of Bogotá, especially the neighbourhoods north of the Avenida Chile (Calle 72) in Chapinero and west of the Autopista Norte (Avenida 30), rest upon the Sabana Formation, where the unconsolidated shales cause frequent fissures in the roads constructed in the Colombian capital. The southeastern part of Bogotá, including the historic centre, rests upon the more competent Tunjuelo Formation.[3]

Regional correlations

[edit]- Legend

- group

- important formation

- fossiliferous formation

- minor formation

- (age in Ma)

- proximal Llanos (Medina)[note 1]

- distal Llanos (Saltarin 1A well)[note 2]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Acosta & Garay, 2002, p.65

- ^ a b c d Montoya & Reyes, 2005, p.72

- ^ a b c d Guerrero, 1992, p.6

- ^ a b Guerrero, 1993, p.9

- ^ a b c Guerrero, 1996, p.3

- ^ a b Guerrero, 1996, p.4

- ^ Guerrero, 1996, p.5

- ^ Villarroel et al., 2001, p.84

- ^ Guerrero, 1993, p.7

- ^ Guerrero, 1996, p.10

- ^ Hoyos et al., 2015, p.265

- ^ Urrego et al., 2016, p.703

- ^ Scott & Meyers, 1994, p.390

- ^ De Porta, 1961, p.52

- ^ Bürgl, 1956

- ^ a b Hammen, 1986, p.30

- ^ Correal Urrego, 1990, p.77

- ^ De Porta, 1960

- ^ Correal Urrego, 1993, p.4

- ^ Hammen, 1986, p.29

- ^ Mothé et al., 2016a

- ^ Mothé et al., 2016b

- ^ Mothé & Avilla, 2015

- ^ Mothé et al., 2012

- ^ Cooke, 1988, p.180

- ^ Zonneveld, 1968, p.205

- ^ Gómez Londoño, 2005, p.281

- ^ (in Spanish) Por qué se hunde la Sabana de Bogotá - El Tiempo

- ^ a b c d e f García González et al., 2009, p.27

- ^ a b c d e f García González et al., 2009, p.50

- ^ a b García González et al., 2009, p.85

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Barrero et al., 2007, p.60

- ^ a b c d e f g h Barrero et al., 2007, p.58

- ^ Plancha 111, 2001, p.29

- ^ a b Plancha 177, 2015, p.39

- ^ a b Plancha 111, 2001, p.26

- ^ Plancha 111, 2001, p.24

- ^ Plancha 111, 2001, p.23

- ^ a b Pulido & Gómez, 2001, p.32

- ^ Pulido & Gómez, 2001, p.30

- ^ a b Pulido & Gómez, 2001, pp.21-26

- ^ Pulido & Gómez, 2001, p.28

- ^ Correa Martínez et al., 2019, p.49

- ^ Plancha 303, 2002, p.27

- ^ Terraza et al., 2008, p.22

- ^ Plancha 229, 2015, pp.46-55

- ^ Plancha 303, 2002, p.26

- ^ Moreno Sánchez et al., 2009, p.53

- ^ Mantilla Figueroa et al., 2015, p.43

- ^ Manosalva Sánchez et al., 2017, p.84

- ^ a b Plancha 303, 2002, p.24

- ^ a b Mantilla Figueroa et al., 2015, p.42

- ^ Arango Mejía et al., 2012, p.25

- ^ Plancha 350, 2011, p.49

- ^ Pulido & Gómez, 2001, pp.17-21

- ^ Plancha 111, 2001, p.13

- ^ Plancha 303, 2002, p.23

- ^ Plancha 348, 2015, p.38

- ^ Planchas 367-414, 2003, p.35

- ^ Toro Toro et al., 2014, p.22

- ^ Plancha 303, 2002, p.21

- ^ a b c d Bonilla et al., 2016, p.19

- ^ Gómez Tapias et al., 2015, p.209

- ^ a b Bonilla et al., 2016, p.22

- ^ a b Duarte et al., 2019

- ^ García González et al., 2009

- ^ Pulido & Gómez, 2001

- ^ García González et al., 2009, p.60

Bibliography

[edit]Geology

[edit]- Acosta Garay, Jorge E.; Ulloa Melo, Carlos E. (2002), Mapa Geológico del Departamento de Cundinamarca - 1:250,000 - Memoria explicativa, INGEOMINAS, pp. 1–108, retrieved 2017-05-06

- Guerrero Uscátegui, Alberto Lobo (1996), Estratigrafía del material no-consolidado en el subsuelo del nororiente de Santafé de Bogotá (Colombia) con algunas notas sobre historia geológica, VII Congreso Colombiano de Geología - I Seminario sobre el Cuaternario, pp. 1–23

- Guerrero Uscátegui, Alberto Lobo (1993), Informe sobre la Cuenca Petrolífera de la Sabana de Bogotá, Colombia, Sociedad Colombiana de Ingenieros, pp. 1–29

- Guerrero Uscátegui, Alberto Lobo (1992), Geología e Hidrogeología de Santafé de Bogotá y su Sabana, Sociedad Colombiana de Ingenieros, pp. 1–20

- Montoya Arenas, Diana María; Reyes Torres, Germán Alfonso (2005), Geología de la Sabana de Bogotá, INGEOMINAS, pp. 1–104

Paleoecology and history

[edit]- Bürgl, Hans (1956), Restos de Megatherium y otros fósiles de Quipile, Cundinamarca, INGEOMINAS, pp. 1–14, retrieved 2017-05-06

- Cooke, Richard (1998), "Human settlement of Central America and northernmost South America (14,000-8000 BP)", Quaternary International, 49/50 (1), Pergamon: 177–190, Bibcode:1998QuInt..49..177C, doi:10.1016/S1040-6182(97)00062-1

- Correal Urrego, Gonzalo (1993), "Nuevas evidencias culturales pleistocénicas y megafauna en Colombia", Boletín de Arqueología, 1: 3–12

- Correal Urrego, Gonzalo (1990), "Evidencias culturales durante el Pleistocene y Holoceno de Colombia - Cultural evidences during the Pleistocene and Holocene of Colombia" (PDF), Revista de Arqueología Americana (in Spanish), 1: 69–89, retrieved 2017-05-06

- Gómez Londoño, Ana María (2005), Lo muisca: el diseño de una cartografía de centro. Chigys Mie: el mundo de los muiscas recreado por la condesa alemana Gertrud von Podewils Dürniz in "Muiscas: representaciones, cartografías y etnopolíticas de la memoria", Universidad La Javeriana, pp. 248–291

- Van der Hammen, Thomas (1986), "Cambios medioambientales y la extinción del mastodonte en el norte de los Andes", Revista de Antropología, Universidad de los Andes, II: 27–34

- Hoyos, Natalia; Monsalve, O.; Berger, G.W.; Antinao, J.L.; Giraldo, H.; Silva, C.; Ojeda, G.; Bayona, G.; Escobar, J.; Montes, C. (2015), "A climatic trigger for catastrophic Pleistocene–Holocene debris flows in the Eastern Andean Cordillera of Colombia", Journal of Quaternary Science, 30 (3), John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: 258–270, Bibcode:2015JQS....30..258H, doi:10.1002/jqs.2779

- De Porta, Jaime (1961), "La posición estratigráfica de la fauna de Mamíferos del pleistoceno de la Sabana de Bogotá", Boletín de Geología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, 7: 37–54, retrieved 2017-05-06

- De Porta, Jaime (1960), "Los Equidos fósiles de la Sabana de Bogotá", Boletín de Geología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, 4: 51–78, retrieved 2017-05-06

- Rutter, N.; Coronato, A.; Helmens, K.; Rabassa, J.; Zárate, M. (2012), Glaciations in North and South America from the Miocene to the Last Glacial Maximum, Springer, pp. 1–67

- Scott, David A.; Meyers, Pieter (1994), Archaeometry of Pre-Columbian sites and artifacts, The Getty Conservation Institute, pp. 1–437

- Torres, Vladimir; Vandenberghe, Jeff; Hooghiemstra, Henry (2005), "An environmental reconstruction of the sediment infill of the Bogotá basin (Colombia) during the last 3 million years from abiotic and biotic proxies", Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 226 (1–2), Elsevier: 127–148, Bibcode:2005PPP...226..127T, doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.05.005

- Urrego, Dunia H.; Hooghiemstra, Henry; Rama Corredor, Oscar; Martrat, Belén; Grimalt, Joan O.; Thompson, Lonnie; Bush, Mark B.; González Carranza, Zaire; Hanselman, Bryan Valencia and César Velásquez Ruiz, Jennifer (2016), "Millennial-scale vegetation changes in the tropical Andes using ecological grouping and ordination methods", Climate of the Past, 12 (3): 697–711, Bibcode:2016CliPa..12..697U, doi:10.5194/cp-12-697-2016, hdl:11245.1/a6c73051-96f3-4abc-ab2d-fa66bce407a0

- Villarroel, Carlos; Concha, Ana Elena; Macía, Carlos (2001), "El Lago Pleistoceno de Soatá (Boyacá, Colombia): Consideraciones estratigráficas, paleontológicas y paleoecológicas", Geología Colombiana, 26, Universidad Nacional de Colombia: 79–93

- Zonneveld, Jan Isaak Samuel (1968), Quaternary climatic changes in the Caribbean and N. South America, pp. 203–208

Proposed reclassification of gomphotheres

[edit]- Mothé, Dimila; Dos Santos Avilla, Leonardo; Asevedo, Lidiane; Borges Silva, Leon; Rosa, Mariane; Labarca Encina, Ricardo; Souberlich, Esteban; Soibelzon, José Luis; D. Ríos, Ascanio D. Rincón, Gina Cardoso de Oliveira and Renato Pereira Lopes, Sergio Roman Carrion (2017), "Sixty years after 'The mastodonts of Brazil': The state of the art of South American proboscideans (Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae)", Quaternary International, 443: 52–64, Bibcode:2017QuInt.443...52M, doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2016.08.028, hdl:11336/48585, retrieved 2017-05-07

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mothé, Dimila; Ferretti, Marco P.; Avilla, Leonardo S. (2016b), "The Dance of Tusks: Rediscovery of Lower Incisors in the Pan-American Proboscidean Cuvieronius hyodon Revises Incisor Evolution in Elephantimorpha", PLoS ONE, 11 (1): 1–19, Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1147009M, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147009, PMC 4710528, PMID 26756209

- Mothé, Dimila; Avilla, Leonardo S. (2015), "Mythbusting evolutionary issues on South American Gomphotheriidae (Mammalia: Proboscidea)", Quaternary Science Reviews, 110: 23–35, doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.12.013, retrieved 2017-05-07

- Mothé, Dimila; Avilla, Leonardo S.; Cozzuol, Mário; Winck, Gisele R. (2012), "Taxonomic revision of the Quaternary gomphotheres (Mammalia: Proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae) from the South American lowlands", Quaternary International, 276–277: 2–7, Bibcode:2012QuInt.276....2M, doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.05.018, retrieved 2017-05-07

Maps

[edit]- Buitrago, José Alberto; Terraza M., Roberto; Etayo, Fernando (1998), Plancha 228 - Santafé de Bogotá Noreste - 1:100,000, INGEOMINAS, p. 1, retrieved 2017-06-06

- Gómez, J.; Montes, N.E.; Nivia, Á.; Diederix, H. (2015), Plancha 5-09 del Atlas Geológico de Colombia 2015 – escala 1:500,000, Servicio Geológico Colombiano, p. 1, retrieved 2017-05-06

- Various, Authors (1997), Mapa geológico de Santa Fe de Bogotá – Geological Map Bogotá – 1:50,000 (PDF), INGEOMINAS, p. 1, retrieved 2017-05-06