Sacred Harp singing is a tradition of sacred choral music that originated in New England and was later perpetuated and carried on in the American South. The name is derived from The Sacred Harp, a ubiquitous and historically important tunebook printed in shape notes. The work was first published in 1844 and has reappeared in multiple editions ever since. Sacred Harp music represents one branch of an older tradition of American music that developed over the period 1770 to 1820 from roots in New England, with a significant, related development under the influence of "revival" services around the 1840s. This music was included in, and became profoundly associated with, books using the shape note style of notation popular in America in the 18th and early 19th centuries.[1]

Sacred Harp music is performed a cappella (voice only, without instruments) and originated as Protestant music.

The music and its notation

[edit]The name of the tradition comes from the title of the shape-note book from which the music is sung, The Sacred Harp. This book exists today in various editions, discussed below.

In shape-note music, notes are printed in special shapes that help the reader identify them on the musical scale. There are two prevalent systems, one using four shapes, and one using seven. In the four-shape system used in The Sacred Harp, each of the four shapes is connected to a particular syllable, fa, sol, la, or mi, and these syllables are employed in singing the notes,[2] just as in the more familiar system that uses do, re, mi, etc. (see solfege). The four-shape system is able to cover the full musical scale because each syllable-shape combination other than mi is assigned to two distinct notes of the scale. For example, the C major scale would be notated and sung as follows:

The shape for fa is a triangle, sol an oval, la a rectangle, and mi a diamond.

In Sacred Harp singing, pitch is not absolute. The shapes and notes designate degrees of the scale, not particular pitches. Thus for a song in the key of C, fa designates C and F; for a song in G, fa designates G and C, and so on; hence it is called a moveable "do" system.

When Sacred Harp singers begin a song, they normally start by singing it with the appropriate syllable for each pitch, using the shapes to guide them. For those in the group not yet familiar with the song, the shapes help with the task of sight reading. The process of reading through the song with the shapes also helps fix the notes in memory. Once the shapes have been sung, the group then sings the verses of the song with their printed words.

Singing Sacred Harp music

[edit]

Sacred Harp groups always sing a cappella, that is to say, without accompanying instruments.[3][4] The singers arrange themselves in a hollow square, with rows of chairs or pews on each side assigned to each of the four parts: treble, alto, tenor, and bass. The treble and tenor sections are usually mixed, with men and women singing the notes an octave apart.

There is no single leader or conductor; rather, the participants take turns in leading. The leader for a particular round selects a song from the book, and "calls" it by its page number. Leading is done in an open-palm style, standing in the middle of the square facing the tenors.

The pitch at which the music is sung is relative; there is no instrument to give the singers a starting point. The leader, or else some particular singer assigned to the task, finds a good pitch with which to begin and intones it to the group. The singers reply with the opening notes of their own parts, and then the song begins immediately.

The music is usually sung not literally as it is printed in the book, but with certain deviations established by custom.

As the name implies, Sacred Harp music is sacred music and originated as Protestant Christian music. Many of the songs in the book are hymns that use words, meters, and stanzaic forms familiar from elsewhere in Protestant hymnody. However, Sacred Harp songs are quite different from "mainstream" Protestant hymns in their musical style: some tunes, known as fuguing tunes, contain sections that are polyphonic in texture, and the harmony tends to deemphasize the interval of the third in favor of fourths and fifths. In their melodies, the songs often use the pentatonic scale or similar "gapped" (fewer than seven-note) scales.

In their musical form, Sacred Harp songs fall into three basic types. Many are ordinary hymn tunes, mostly composed in four-bar phrases and sung in multiple verses. Fuguing tunes contain a prominent passage about 1/3 of the way through in which each of the four choral parts enters in succession, in a way resembling a fugue. Anthems are longer songs, less regular in form, that are sung through just once rather than in multiple verses.[5]

Venues for singing

[edit]Sacred Harp singing normally occurs not in church services, but in special gatherings or "singings" arranged for the purpose. Singings can be local, regional, statewide, or national. Small singings are often held in homes, with perhaps only a dozen singers. Large singings have been known to have more than a thousand participants. The more ambitious singings include an ample potluck dinner in the middle of the day, traditionally called "dinner on the grounds".

Some of the largest and oldest annual singings are called "conventions". The oldest Sacred Harp convention was the Southern Musical Convention, organized in Upson County, Georgia in 1845. The two oldest surviving Sacred Harp singing conventions are the Chattahoochee Musical Convention (organized in Coweta County, Georgia in 1852), and the East Texas Sacred Harp Convention (organized as the East Texas Musical Convention in 1855).

Sacred Harp music as participatory music

[edit]Sacred Harp singers view their tradition as a participatory one, not a passive one. Those who gather for a singing sing for themselves and for each other, and not for an audience. This can be seen in several aspects of the tradition.

First, the seating arrangement (four parts in a square, facing each other) is clearly intended for the singers, not for external listeners. Non-singers are always welcome to attend a singing, but typically they sit among the singers in the back rows of the tenor section, rather than in a designated separate audience location.

The leader, being equidistant from all sections, in principle hears the best sound. The often intense sonic experience of standing in the center of the square is considered one of the benefits of leading, and sometimes a guest will be invited as a courtesy to stand next to the leader during a song.

The music itself is also meant to be participatory. Most forms of choral composition place the melody on the top (treble) line, where it can be best heard by an audience, with the other parts written so as not to obscure the melody. In contrast, Sacred Harp composers have aimed to make each musical part singable and interesting in its own right, thus giving every singer in the group an absorbing task.[6] For this reason, "bringing out the melody" is not a high priority in Sacred Harp composition, and indeed it is customary to assign the melody not to the trebles but to the tenors. Fuguing tunes, in which each section gets its moment to shine, also illustrate the importance in Sacred Harp of maintaining the independence of each vocal part.

History of Sacred Harp singing

[edit]Marini (2003) traces the earliest roots of Sacred Harp to the "country parish music" of early 18th century England. This form of rural church music evolved a number of the distinctive traits that were passed on from tradition to tradition, until they ultimately became part of Sacred Harp singing. These traits included the assignment of the melody to the tenors, harmonic structure emphasizing fourths and fifths, and the distinction between the ordinary four-part hymn ("plain tune"), the anthem, and the fuguing tune. Several composers of this school, including Joseph Stephenson and Aaron Williams, are represented in the 1991 Edition of The Sacred Harp. For further information on the English roots of Sacred Harp music, see West gallery music.[7]

Around the mid-18th century, the forms and styles of English country parish music were introduced to America, notably in a new tunebook called Urania, published 1764 by the singing master James Lyon.[8] This stimulus soon led to the development of a robust native school of composition, signaled by the 1770 publication of William Billings's The New England Psalm Singer, and then by a great number of new compositions by Billings and those who followed in his path. The work of these composers, sometimes called the "First New England School", forms a major part of the Sacred Harp to this day.

Billings and his followers worked as singing masters, who led singing schools. The purpose of these schools was to train young people in the correct singing of sacred music. This pedagogical movement flourished, and led ultimately to the invention of shape notes, which originated as a way to make the teaching of singing easier. The first shape note tunebook appeared in 1801: The Easy Instructor[9] by William Smith and William Little. At first, Smith and Little's shapes competed with a rival system, created by Andrew Law (1749–1821) in his The Musical Primer of 1803. Although this book came out two years later than Smith and Little's book, Law claimed earlier invention of shape notes. In his system, a square indicated fa, a circle sol, a triangle la and a diamond, mi. Law used the shaped notes without a musical staff. The Smith and Little shapes ultimately prevailed.

Shape notes became very popular, and during the first part of the nineteenth century, a whole series of shape note tunebooks appeared, many of which were widely distributed. As the population spread west and south, the tradition of shape note singing expanded geographically. Composition flourished, with the new music often drawing on the tradition of folk song for tunes and inspiration. Probably the most successful shape note book prior to The Sacred Harp was William Walker's Southern Harmony, published in 1835 and still in use today.[10]

Even as they flourished and spread, shape notes and the kind of participatory music which they served came under attack. The critics were from the urban-based "better music" movement, spearheaded by Lowell Mason, which advocated a more "scientific" style of sacred music, more closely based on the harmonic styles of contemporaneous European music. The new style gradually prevailed. Shape notes and their music disappeared from the cities prior to the Civil War, and from the rural areas of the Northeast and Midwest in the following decades. However, they retained a haven in the rural South, which remained a fertile territory for the creation of new shapenote publications.[11]

The arrival of The Sacred Harp

[edit]Sacred Harp singing came into being with the 1844 publication of Benjamin Franklin White and Elisha J. King's The Sacred Harp. It was this book, now distributed in several different versions, that came to be the shape note tradition with the largest number of participants.

B. F. White (1800–1879) was originally from Union County, South Carolina, but since 1842 had been living in Harris County, Georgia. He prepared The Sacred Harp in collaboration with a younger man, E. J. King, (c. 1821–44), who was from Talbot County, Georgia. Together they compiled, transcribed, and composed tunes, and published a book of over 250 songs.

King died soon after the book was published, and White was left to guide its growth. He was responsible for organizing singing schools and conventions at which The Sacred Harp was used as the songbook. During his lifetime, the book became popular and would go through three revisions (1850, 1859, and 1869), all produced by committees consisting of White and several colleagues working under the auspices of the Southern Musical Convention. The first two new editions simply added appendices of new songs to the back of the book. The 1869 revision was more extensive, removing some of the less popular songs and adding new ones in their places. From the original 262 pages, the book was expanded by 1869 to 477. This edition was reprinted and continued in use for several decades.

Origin of the modern editions

[edit]Around the turn of the 20th century, Sacred Harp singing entered a period of conflict over the issue of traditionalism. The conflict ultimately split the community.[12]

B. F. White had died in 1879 before completing a fourth revision of his book; thus the version that Sacred Harp participants were singing from was by the turn of the century over three decades old. During this time, the musical tastes of Sacred Harp's traditional adherents, the inhabitants of the rural South, had changed in important ways. Notably, gospel music – syncopated and chromatic, often with piano accompaniment – had become popular, along with a number of church hymns of the "mainstream" variety, such as "Rock of Ages". Seven-shape notation systems had appeared and won adherents away from the older four-shape system (see shape note for details). As time passed, Sacred Harp singers doubtless became aware that what they were singing had become quite distinct from contemporary tastes.

The natural path to take—and the one ultimately taken—would be to assert the archaic character of Sacred Harp as an outright virtue. In this view, Sacred Harp should be treasured as a time-tested musical tradition, standing above current trends of fashion. The difficulty with adopting traditionalism as a guiding doctrine was that different singers had different opinions about just what form the stable, traditionalized version of Sacred Harp would take.

The first move was made by W. M. Cooper, of Dothan, Alabama, a leading Sacred Harp teacher in his own region, but not part of the inner circle of B. F. White's old colleagues and descendants. In 1902 Cooper prepared a revision of The Sacred Harp that, while retaining most of the old songs, also added new tunes that reflected more contemporary music styles.[13] Cooper made other changes, too:

- He retitled many old songs. These songs were formerly named by their tune, using arbitrarily chosen place names ("New Britain", "Northfield", "Charlestown"). The new names were based on the text; thus "New Britain" became "Amazing Grace", "Northfield" became "How Long, Dear Savior", and so on. The old system was intended in colonial times to permit mixing and matching of tunes and texts, but was unnecessary in a system where the pairing of tune and text was fixed.

- He transposed some songs into new keys. This is thought to have brought the notation closer to actual performing practice.

- He wrote new alto parts for the many songs that originally just had three vocal lines.

The Cooper revision was a success, being widely adopted in many areas of the South, such as Florida, southern Alabama, and Texas, where it has continued as the predominant Sacred Harp book to this day. The "Cooper book", as it is now often called, was revised by Cooper himself in 1907 and 1909. His son-in-law published the book in 1927, including an appendix compiled by revision committee. The Sacred Harp Book Company was formed in 1949, and subsequent revision has been supervised by editorial committees under its instruction. New editions were issued in 1950, 1960, 1992, 2000, 2006 and 2012.

In the original core geographic area of Sacred Harp singing, northern Alabama and Georgia, the singers did not in general take to the Cooper book, as they felt it deviated too far from the original tradition. Obtaining a new book for these singers was made more difficult by the fact that B. F. White's son James L. White, who would have been the natural choice to prepare a new edition, was a non-traditionalist. His "fifth edition" (1909)[14] won little support among singers, while his "fourth edition with supplement" (1911) enjoyed some success in a few areas.[15] Ultimately, a committee headed by Joseph Stephen James produced an edition entitled Original Sacred Harp (1911) that largely satisfied the wishes of this community of singers.[16]

The James edition was further revised in 1936 by a committee under the leadership of the brothers Seaborn and Thomas Denson, both influential singing school teachers. Both died shortly before the project was complete, and the remaining work was overseen by Paine Denson, son of Thomas. This book was entitled Original Sacred Harp, Denson Revision, and was itself revised 1960, 1967, and 1971;[17] a more thorough revision and remodeling of this book, overseen by Hugh McGraw, is known simply as the "1991 Edition", though some singers still call it the "Denson book".

Even the highly traditionalist James and Denson books followed Cooper in adding alto parts to most of the old three-part songs (these alto parts led to an unsuccessful lawsuit by Cooper).[18] Some people (see for instance the reference by Buell Cobb given below) believe that the new alto parts imposed an esthetic cost by filling in the former stark open harmonies of the three-part songs. Wallace McKenzie argues to the contrary, basing his view on a systematic study of representative songs.[19] In any event, there is little support today for abandoning the added alto parts, since most singers give a high priority to giving every side of the square its own part to sing.

It was thus that the traditionalism debate split the Sacred Harp community, and there seems little prospect that it will ever reunite under a single book. However, there have been no further splits. Both the Denson and the Cooper groups adopted traditionalist views for the particular form of Sacred Harp they favored, and these forms have now been stable for about a century.

The strength of traditionalism can be seen in the front matter of the two hymnbooks. The Denson book is forthrightly Biblical in its defense of tradition:

DEDICATED TO

All lovers of Sacred Harp Music, and to the memory of the illustrious and venerable patriarchs who established the Traditional Style of Sacred Harp singing and admonished their followers to "seek the old paths and walk therein".[20]

The Cooper book also shows a warm appreciation of tradition:

May God bless everyone as we endeavor to promote and enjoy Sacred Harp music and to continue the rich tradition of those who have gone before us.

To say that both communities are traditionalist does not mean they discourage the creation of new songs. To the contrary, it is part of the tradition that musically creative Sacred Harp singers should become composers themselves and add to the canon. The new compositions are prepared in traditional styles, and could be considered a kind of tribute to the older material. New songs have been incorporated into editions of The Sacred Harp throughout the 20th century.

Other Sacred Harp books

[edit]Two other books are currently used by Sacred Harp singers. A few singers in north Georgia employ the "White book", an expanded version of the 1869 B. F. White edition edited by J. L. White. African-American Sacred Harp singers, although primarily users of the Cooper book, also make use of a supplementary volume, The Colored Sacred Harp, produced by Judge Jackson (1883–1958) in 1934 and later revised in two subsequent editions. In his book Judge Jackson and The Colored Sacred Harp, Joe Dan Boyd identified four regions of Sacred Harp singing among African-Americans: eastern Texas (Cooper book), northern Mississippi (Denson book), south Alabama and Florida (Cooper book), and New Jersey (Cooper book). The Colored Sacred Harp is limited to the New Jersey and south Alabama–Florida groups. Sacred Harp was "exported" from south Alabama to New Jersey. It appears to have died out among the African-Americans in eastern Texas.

In summary, three revisions of and one companion book to The Sacred Harp are currently in use in Sacred Harp singing:

- The Sacred Harp, 1991 edition (the "Denson book"). Carrollton, Georgia: Sacred Harp Publishing Company.

- The Sacred Harp, Revised Cooper Edition, 2012. Samson, Alabama: The Sacred Harp Book Company.

- The Sacred Harp, J. L. White Fourth Edition, with Supplement (the "White book"). Atlanta, Georgia: J. L. White. Released 1911; republished 2007.

- The Colored Sacred Harp. Ozark, Alabama: Judge Jackson. [3rd revised edition (1992) includes rudiments by H. J. Jackson (son of J. Jackson) and an autobiography of Judge Jackson].

Sacred Harp books generally contain a section on rudiments, describing the basics of music and Sacred Harp singing.

The spread of Sacred Harp singing in modern times

[edit]In recent years, Sacred Harp singing has experienced a resurgence in popularity, as it is discovered by new participants who did not grow up in the tradition.[21] New singers typically strive to follow the original southern customs at their singings. Traditional singers have responded to this need by providing help in orienting the newcomers. For instance, the Rudiments section of the 1991 Denson edition includes information on how to hold a singing; this information would be superfluous in a traditional context, but is important for a group starting up on its own. The tradition of the singing master is still carried on today, and singing masters from traditional Sacred Harp regions often travel outside the South to teach. In recent years an annual summer camp has been established, at which newcomers can learn to sing Sacred Harp.[22]

The U.S. beyond the South

[edit]There are now strong Sacred Harp singing communities in most major urban areas of the United States, and in many rural areas, as well.[23] One of the first groups of singers formed outside the traditional Southern home region of Sacred Harp singing was in the Chicago area.[24] The first Illinois convention was held in 1985, with enthusiastic and strongly proactive support by prominent Southern traditional singers.[24] The Midwest Convention is now acknowledged to be one of the major American conventions, attracting hundreds of singers from all over the US and abroad.[24] Similarly, the Sacred Harp singing community in western New England has become a prominent one in recent years; the late songleader Larry Gordon has been credited with re-popularizing Sacred Harp singing in northern New England.[25] In March 2008, the 2008 Western Massachusetts Sacred Harp Convention attracted over 300 singers from 25 states and a number of foreign countries.[26] Other prominent singing conventions outside the South include, for example, the Keystone Convention in Pennsylvania, the Missouri Convention, and the Minnesota State Convention, which began in 1990.[27]

Sacred Harp Singing beyond the US

[edit]In more recent times Sacred Harp singing has spread beyond the borders of the United States.

The United Kingdom has had an active Sacred Harp community since the 1990s.[28] The first UK Sacred Harp convention took place in 1996.[29] There are regular singings in London,[30][31] the Home Counties, the Midlands, Yorkshire,[32] Lancashire, Manchester, Brighton,[33] Newcastle,[34] southwest England,[35] Bristol,[36] as well as in Scotland.[37]

Canada has a decades-long tradition of Sacred Harp singing, particularly in Southern Ontario and the Eastern Townships of Quebec. Singings have been organized weekly in Montreal, Quebec since 2011, as well as a monthly afternoon sing, and the first Montreal all-day sing took place in the spring of 2016.[38] Sacred Harp singing has happened on a monthly basis for years in Toronto.

Australia has had Sacred Harp singing since 2001, and singings are held regularly in Melbourne,[39] Sydney,[40] Canberra[41] and Blackwood.[42] The first Australian All Day Singing was held in Sydney in 2012.[43]

In January 2009, Sacred Harp singing was introduced to Ireland, by Juniper Hill of University College Cork, spreading quickly from a class module into the wider community. In March 2011 U.C.C. hosted the first annual Ireland Sacred Harp Convention, and the Cork community held their first All-Day Singing on 22 October 2011. There are now also growing Sacred Harp communities in Belfast and Dublin.[44]

In the most recent development, Sacred Harp singing has expanded beyond the limits of English-speaking countries to mainland Europe. In 2008 a singing community was established in Poland (which hosted the first Camp Fasola Europe in September 2012).[45] In Germany there are regular weekly or monthly singings in Bremen,[46] Hamburg,[47] Berlin,[48] Cologne[49] and Munich, most of them with their own annual All-Day singings. Elsewhere in Germany, singers meet irregularly in Frankfurt, Gießen and Nürnberg. Recently groups have started up in Amsterdam,[50] Paris and Clermont-Ferrand,[51] Oslo, Norway, and Uppsala, Sweden.[52] Both the Swedish and Norwegian groups have arranged all-day singings; the 8th Oslo All-Day Singing was held on June 1, 2024 (starting on Friday night May 31, and ending Sunday afternoon June 2).

Regular singings also take place in Israel,[53] and in April 2016, an all-day singing was held in Paris, France.[54]

Use in popular works

[edit]Sacred Harp singing appears as diegetic music in the films Cold Mountain (2004)[55][56] and Lawless (2012), and as background music in The Ladykillers (2004).[57]

The 2010 song "Tell Me Why" by M.I.A. includes a sample of "The Last Words of Copernicus" by Sarah Lancaster, recorded at the 1959 United Sacred Harp Convention in Fyffe, Alabama, by Alan Lomax.[58] The album version of Bruce Springsteen's "Death to My Hometown" (2012) also samples this recording.[59]

Electronic musician Holly Herndon's 2019 track "Frontier" includes a performance of Herndon's music by a singing class in Berlin, Germany.[60]

The 2014 animated miniseries Over the Garden Wall features an original Sacred Harp composition in the second episode, "Hard Times at the Huskin' Bee".[61]

Origins of the music

[edit]The music used in Sacred Harp singing is eclectic. Most of the songs can be assigned to one of four historical layers.

- The oldest of these layers comes from 18th century New England, and represents a rendition in shape notes of the work of outstanding early American composers such as William Billings and Daniel Read, who worked as singing masters.

- A second layer comes from the decades around 1830, following the migration of the shape note tradition to the rural South. Many of the songs in this layer are believed to be originally secular folk tunes, harmonized in parts and given religious lyrics. As one would expect from the folk origin of such music, it often emphasizes the notes of the pentatonic scale. They often employ stark, vivid harmonies based on open fifths. Most of the songs of this layer were originally composed in just three parts (treble, tenor, bass), with the altos added later, as noted above.

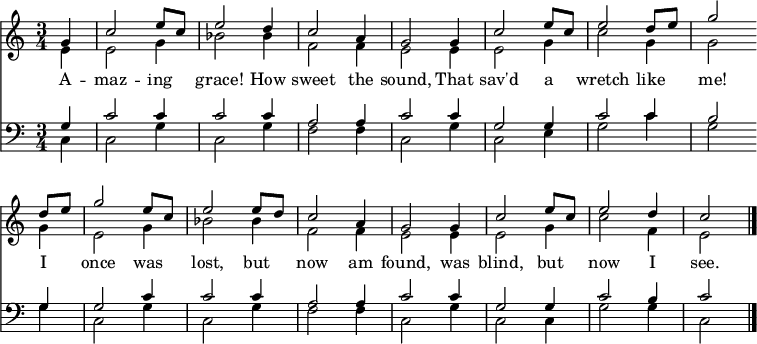

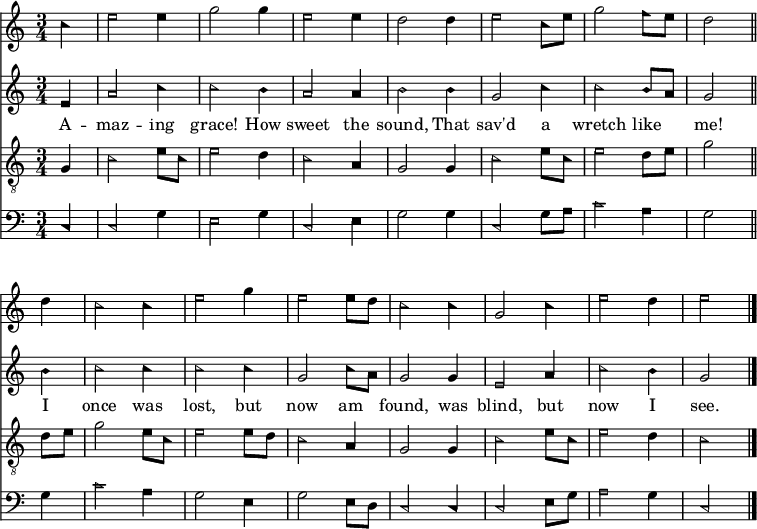

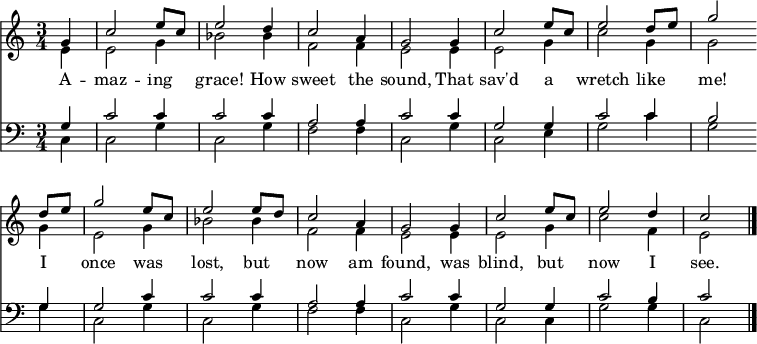

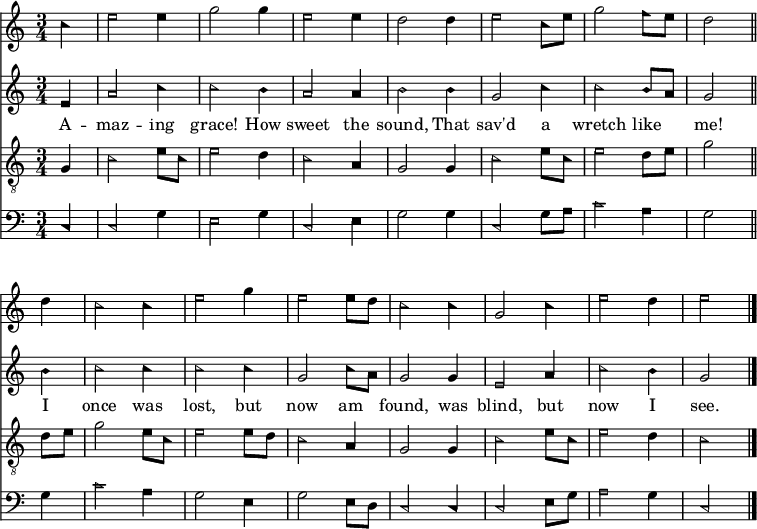

The sound of this musical layer, as well as to some extent The Sacred Harp in general, can be observed by comparing versions of the well-known hymn "Amazing Grace", which is familiar to many Americans in a form such as the following:

In The Sacred Harp (1991 edition), "Amazing Grace" is harmonized quite differently. Note that the "air", or melody, is in the tenor.

- A third layer of Sacred Harp music is from the mid nineteenth century and represents the popular sensibility of that era. A number of these mid-century works have an almost primal simplicity—the harmony is essentially a single extended major chord, and the parts a decoration in slow tempo of that chord.

- The most recent layer consists of the songs that were added to the books during the twentieth century. These are the work of musically creative participants in the Sacred Harp tradition, who strove to create songs that would fit into the existing tradition by adopting the style of one of the earlier periods. About a sixth of the Denson edition is taken up with such compositions, dating from as recently as 1990. The twentieth-century composers often have recycled their lyrics from earlier Sacred Harp songs (or from their sources, such as the work of the 18th-century hymnodist Isaac Watts). A number of these modern compositions have become favorites of the singing community, and it is anticipated that future editions of The Sacred Harp will also include new songs.

There are a few additional songs in The Sacred Harp, 1991 edition that cannot be assigned to any of these four main layers. There are some very old songs of European origin, as well as songs from the English rural tradition that inspired the early New England composers. There are also a handful of songs by European classical composers (Ignaz Pleyel, Thomas Arne, and Henry Rowley Bishop). The book even includes five hymns by Lowell Mason, long ago the implacable enemy of the tradition that The Sacred Harp has preserved to this day.[62]

The description just given is based on The Sacred Harp, 1991 edition, also known as the Denson edition. The widely used "Cooper" edition overlaps considerably (about 60%) in content, but also includes many later songs. A detailed comparison of the two editions has been made by Sacred Harp scholar Gaylon L. Powell.[63]

Other books with the title Sacred Harp

[edit]The Sacred Harp was a popular name for 19th century hymn and tune books, with no fewer than four bearing the title. The first of these was compiled by John Hoyt Hickok and printed in Lewistown, Pennsylvania in 1832. The second was compiled by Lowell and Timothy Mason and printed in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1834, as part of the "better music" movement mentioned above. The publisher released their book as a shape note edition, while they preferred to urbanize their audience by releasing a round note edition.[64][65]

The third Sacred Harp was the one by B. F. White and E. J. King (1844), the origin of today's Sacred Harp singing tradition.

Lastly, according to W. J. Reynolds, writing in Hymns of Our Faith, there was yet a fourth Sacred Harp – The Sacred Harp published by J. M. D. Cates in Nashville, Tennessee in 1867.

Comedic parody

[edit]In order to increase accessibility to the Sacred Harp tunes, Jo Puma – Wild Choir Music was published by the Machinists Union Press in 2013, combining the unaltered Sacred Harp arrangements with new secular lyrics by Secretary Michael.[66]

See also

[edit]- Awake, My Soul: The Story of the Sacred Harp

- Chattahoochee Musical Convention

- East Texas Musical Convention

- List of shape-note tunebooks

- Sacred Harp hymnwriters and composers

- Shape note

- Southwest Texas Sacred Harp Singing Convention

Notes

[edit]- ^ David Warren Steel, "Shape-note hymnody", in Grove Music Online (Oxford University Press: article updated 16 October 2013) Subscription required

- ^ This is a simplified version of Guidonian solmization which was also used in Elizabethan England: see Solfège#Origin

- ^ In particular, no harps are present. The term "Sacred Harp" is sometimes taken by singers to be a metaphor for the human voice Anon. 1940, p. 127.

- ^ On a number of early historical recordings, a piano or parlor organ accompanied the singers. In the ensuing decades, the practice of using such instruments has evidently died out.

- ^ The harmony and form of Sacred Harp music are discussed in Cobb 1978, ch. 2[incomplete short citation] and in more technical detail in Horn 1970.

- ^ Horn 1970, p. 86.

- ^ Sources for this paragraph: Marini 2003, p. 77, Temperley 1983, and the essay "Distant Roots of Shape Note Music" by Keith Willard, posted at the fasola.org web site Archived 16 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Marini 2003, p. 78.

- ^ Dick Hulan writes, "My copy of William Smith's Easy Instructor, Part II (1803) attributes the invention [of shape notes] to 'J. Conly of Philadelphia'."[This quote needs a citation] According to David Warren Steel, in John Wyeth and the Development of Southern Folk Hymnody, "This notation was invented by Philadelphia merchant John Connelly, who on 10 March 1798 signed over his rights to the system to Little and Smith."[citation needed] Andrew Law also laid claim to the invention of the shape note system.

- ^ The shape note systems continued to evolve throughout the 19th century; for a more complete history, see shape note.

- ^ Source for this paragraph: Marini 2003, p. 81. Evidence that Americans outside the rural South were slow, even reluctant, to give up their old music is given in Horn 1970, ch. 12.

- ^ The primary source for this section is Cobb 2001, ch. 4.

- ^ Miller 2004 characterizes Cooper book style thus: it "contains a greater proportion of "camp meeting" songs than the Denson book, with more compressed part-writing, chromatic harmonies, and choruses characterized by call-and-response rather than "fuging" style. Denson book singers generally say that the Cooper book sounds more like "new book or gospel singing".

- ^ This edition may be viewed in digital form at [1] Archived 19 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Cobb 2001, pp. 98–110.

- ^ Cobb 2001, pp. 94–98.

- ^ Cobb 2001, pp. 110–117.

- ^ Cobb 2001, pp. 95–96.

- ^ McKenzie 1989 further judges that the Cooper alto parts were more successful than the Denson ones in retaining the original harmonic style.

- ^ The passage quotes Jeremiah 6:16: "Thus saith the LORD, Stand ye in the ways, and see, and ask for the old paths, where is the good way, and walk therein, and ye shall find rest for your souls."

- ^ For an extended narrative of this spread, see Bealle 1997, ch. 4.

- ^ Clawson 2011, p. 163.

- ^ A guide to singings that demonstrates this dramatic spread may be found at the "fasola.org" web site, under http://fasola.org/singings/ Archived 21 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c Miller 2004

- ^ Lueck, Ellen (2017). "Sacred Harp Singing in Europe: Its Pathways, Spaces, and Meanings". Dissertation. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "Sacred Harp sing draws followers". Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "22nd Annual Minnesota State Sacred Harp Singing Convention". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "UK Sacred Harp Calendar". UK Sacred Harp Calendar. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "Conventions". United Kingdom Sacred Harp & Shapenote Singing. Edwin and Sheila Macadam. Archived from the original on 4 August 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ^ "London Sacred Harp". Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Music". London Sacred Harp. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Sheffield & South Yorkshire Sacred Harp". Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Brighton Shape Note Singing". Archived from the original on 28 June 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Newcastle Sacred Harp". Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ "South West Shape Note (Cornwall, Devon, Somerset, Dorset and Wiltshire)". Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Bristol Sacred Harp". Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ^ "Shapenote Scotland". Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Montreal Sacred Harp Singers". Facebook. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Facebook". Facebook. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Facebook". Facebook. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Facebook". Facebook. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Blackwood Academy". Facebook. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Australia's First Ever Sacred Harp Singing Convention Hits Sydney". Timber and Steel. 17 September 2012. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Cork Sacred Harp". Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Application form for Camp Fasola Europe" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 June 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ "Sacred Harp Bremen". Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- ^ "Sacred Harp Singing in Hamburg – Sacred Harp Hamburg Singing School – Home". Sacred Harp Singing in Hamburg. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Sacred Harp Berlin". Sacred Harp Berlin. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ "Sacred Harp Cologne". Sacred Harp Cologne. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ "Sacred Harp Amsterdam". Archived from the original on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ "Sacred Harp Auvergne". Facebook. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "406 and More, in Sweden". The Sacred Harp Publishing Company. 31 December 2015. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Facebook". Facebook. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Sacred Harp Paris – 1st All Day Singing". Facebook. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ Wurst, Nancy Henderson (4 January 2004). "'Cold Mountain' shows off sacred singing". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Burghart, Tara (13 February 2004). "Via 'Cold Mountain', old music is revived". The Boston Globe. Associated Press.

- ^ "Sacred Harp in contemporary culture". Sacred Harp Australia. 16 August 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ Chris Tinkham (22 March 2012). "Bruce Springsteen: Wrecking Ball (Columbia) | Under the Radar – Music Magazine". undertheradarmag.com. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ^ Plunkett, John; Karlsberg, Jesse P. (28 March 2012). "Bruce Springsteen's Sacred Harp Sample". The Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter. 1 (1).

- ^ Gray, Julia (2 May 2019). "Holly Herndon – "Frontier"". Stereogum. Prometheus Global Media.

- ^ Resler, Chloe (2022). Musical Narrative and Cultural Context in the Animated Miniseries Over the Garden Wall (Thesis). University of North Colorado.

- ^ See the online Index to the Denson edition: http://fasola.org/indexes/1991/?v=composer Archived 11 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ L. Powell, Gaylon. "Comparison Tune Index". resources.texasfasola.org.

- ^ Jackson (1933b, 395)

- ^ Gould 1853, p. 55.

- ^ "Jo Puma - Wild Choir Music". machinistsunion.org. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

Sources

[edit]- Anon. (1940) Georgia: A guide to its towns and countryside. Compiled and written by workers of the Writers' Program of the Works Progress Administration. University of Georgia Press.

- Bealle, John (1997). Public Worship, Private Faith: Sacred Harp and American Folksong. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-1988-0.

- Clawson, Laura (15 September 2011). I Belong to This Band, Hallelujah!: Community, Spirituality, and Tradition Among Sacred Harp Singers. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-10959-6.

- Cobb, Buell E. (2001). The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music.[full citation needed]

- Gould, Nathaniel Duren (1853). History of Church Music in America. Gould and Lincoln. p. 55.

- Horn, Dorothy D. (1970). Sing to me of Heaven: A Study of Folk and Early American Materials in Three Old Harp Books. University of Florida Press.

- Marini, Stephen A. (2003). Sacred Song in America: Religion, Music, and Public Culture. University of Illinois Press. See chapter 3, "Sacred Harp singing".

- McKenzie, Wallace (1989). "The Alto Parts in the 'True Dispersed Harmony' of The Sacred Harp Revisions". The Musical Quarterly. 73 (73): 153–171. doi:10.1093/mq/73.2.153.

- Miller, Kiri (Winter 2004). "'First Sing the Notes': Oral and Written Traditions in Sacred Harp Transmission". American Music. 22 (4): 475–501. doi:10.2307/3592990. JSTOR 3592990.

- Temperley, Nicholas (1983). The Music of the English Parish Church. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27457-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Boyd, Joe Dan (2002) Judge Jackson and The Colored Sacred Harp. Alabama Folklife Association. ISBN 0-9672672-5-0

See also the bibliographic entries under Shape note.

- Campbell, Gavin James (1997) " 'Old Can Be Used Instead of New': Shape-Note Singing and the Crisis of Modernity in the New South, 1880–1920." Journal of American Folklore 110:169–188.

- Cobb, Buell E. (1989). The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-2371-3.

- Cobb, Buell (2013). Like Cords Around My Heart: A Sacred Harp Memoir. Outskirts Press. ISBN 978-1-4787-0462-1.

- Eastburn, Kathryn (2008) A Sacred Feast: Reflections on Sacred Harp Singing and Dinner on the Ground University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1831-4

- Jackson, George Pullen (1933a) White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-486-21425-7

- Jackson, George Pullen (1933b) "Buckwheat notes", The Musical Quarterly XIX(4):393–400.

- Miller, Kiri (ed.) (2002) The Chattahoochee Musical Convention, 1852–2002: A Sacred Harp Historical Sourcebook. The Sacred Harp Museum. ISBN 1-887617-13-2

- Miller, Kiri (2007) Traveling Home: Sacred Harp Singing and American Pluralism. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-03214-4

- Sommers, Laurie Kay (2010) "Hoboken Style: Meaning and Change in Okefenokee Sacred Harp Singing" Southern Spaces ISSN 1551-2754

- Steel, David Warren with Richard H. Hulan (2010) The Makers of the Sacred Harp. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07760-9

- Wallace, James B. (2007) "Stormy Banks and Sweet Rivers: A Sacred Harp Geography" Southern Spaces ISSN 1551-2754

External links

[edit]This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (August 2021) |

- Fasola Home Page, a web site dedicated to Sacred Harp music

- "Sacred Harp Bremen". Includes all the songs in the Sacred Harp book: lyrics, sheet music and the individual parts sung by a synthesised voice, and a beginners guide. In English and German.

- Sacred Harp Singing by Warren Steel, another web site on the Sacred Harp

- Sacred Harp and Related Shape-Note Music Resources, a large and well-annotated collection of resources on shape-note music

- Sacred Harp Publishing Company, songbooks and other resources

- Public-domain editions: The Sacred Harp (1860), (1911, rev. J. S. James et al.) (for other shape note tunebooks see these links)

- "Wiregrass Sacred Harp Singers Era 1980". Musics of Alabama: A Compilation. Alabama Center for Traditional Culture. Archived from the original on 8 January 2013.

- "Shape Note Singing in Florida". Florida Memory. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- Sacred Harp Music, article on Sacred Harp from the Handbook of Texas online

- Sacred Harp singing in Texas, includes composer sketches, including one of B. F. White

- Shape Note Historical Background

- Sacred Harp Singing historical marker

Online media

[edit]- BostonSing, a large collection of shape-note recordings

- BBC Radio 4 programme about Sacred Harp music