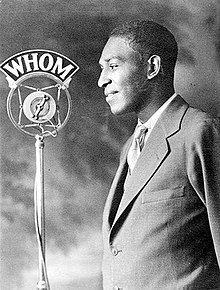

Sherman Maxwell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 18, 1907 |

| Died | July 16, 2008 (aged 100) |

| Occupation | Sportscaster |

Sherman Leander "Jocko" Maxwell (December 18, 1907 – July 16, 2008) was an American sportscaster and chronicler of Negro league baseball.[1] Many veteran journalists of his day, including Sam Lacy of the Baltimore Afro-American, believed that Maxwell was the first African American sports broadcaster in history.[2] It was an assertion that many in the mainstream press also accepted,[3] and Maxwell himself sometimes stated that he had in fact been the first.[4] For much of his life, he was known by the nickname of Jocko.[3] Despite his many accomplishments over a broadcasting career of more than four decades, Maxwell was rarely paid by the radio stations he worked for during his career.[1][3]

Early life

[edit]Sherman Leander Maxwell was born on December 18, 1907, in Newark, New Jersey, where he resided for most of his life.[3] His parents, Bessie and William, named him after the Civil War general, William Tecumseh Sherman.[5] His father was a journalist, one of the few black men of his era to rise to an editorial position at a predominantly white newspaper, The Star-Ledger.[6] He graduated from Central High School in Newark, though he was such a fan of baseball that he intentionally failed high school final exams so he could remain at the school for one more year in order to play for his high school baseball team.[1] He wanted to go to college; but the school of his choice, Panzer College of Physical Education in East Orange (NJ) did not accept black students.[7] He received his nickname of "Jocko" when he was a teenager. He had been passionate about baseball ever since childhood, although he never thought he was good enough to play professionally.[5] One day, Maxwell climbed a tree while watching a baseball game, in an attempt to catch a fly ball; someone yelled, "Hey, look at Jocko!" [3] Jocko The Monkey was the name of a popular performer in 1920s era films and the name stuck.[3]

He later served in the United States Army in Europe during World War II.[3] He served with the Army Special Service Department, a unit that entertained the troops, serving until 1945.[8] Prior to being sent overseas, he married his long-time sweetheart, Mamie Bryant, a social worker, in June 1943.[9] They had two children, a son and a daughter.[10]

Sports broadcasting career

[edit]Maxwell reportedly began his broadcasting career in 1929 at the age of 22 when he began doing a five-minute weekly sports report on WNJR, a radio station based in Newark.[1] (There are some discrepancies as to which station Maxwell first began working at, but most sources point to WNJR).[3] WNJR was known as the "voice of Newark" during the 1920s and was owned by Herman Lubinsky, the co-founder of Savoy Records.[3] However, at the time Jocko went to work there in 1929, the station was known as WNJ; when that station went defunct, it returned to the air later as WNJR.[11] It is believed by many authors and historians of the radio era that Maxwell became the first African American sports reporter.[3] In fact, the black press of the 1930s and early 1940s regularly asserted that Maxwell was the first and only black sportscaster on radio,[12] although some newspapers qualified it by saying he was the only black sports announcer in the East, or in any major city.[13] Maxwell was broadcasting on stations throughout northern New Jersey, and was also heard in New York City, beginning in the early 1930s.[1] He was a sports commentator at station WHOM in Jersey City, where he hosted a program called Sport Hi Lites, and also reported about area teams.[14] He later hosted a sports report called, "Runs, Hits and Errors" on WRNY, a station based in Coytesville, New Jersey, which had a studio in Manhattan at the Roosevelt Hotel.[3] His reports gradually expanded to include interviews with Negro league baseball players.[3] In 1938, he joined station WWRL, where his "Five Star Sports Final" program became very popular; on it, he interviewed some of the biggest stars in pro sports, including Hank Greenberg, Sid Luckman, and Dixie Walker. By 1942, he had been promoted to the station's sports director.[15]

Maxwell later became the public address sports announcer at Ruppert Stadium for the Negro leagues team the Newark Eagles.[3] He initially announced for games only on Sundays.[1] Maxwell continued broadcasting for both games and radio stations until 1967.[3]

Maxwell also founded and managed the Newark Starlings, a mixed race, semi-professional baseball team.[1] He also became a contributing writer to Baseball Digest, where he wrote about subjects ranging from the integration of baseball to Jackie Robinson.[3] In 1940, Maxwell authored a book of interviews with players entitled, Thrills and Spills in Sports.[3] He also submitted stories on the Newark Eagles to the Ledger in Newark, which is the predecessor of The Star-Ledger newspaper.[1] In the 1950s and 1960s, he wrote historical articles about the Negro Leagues; his work was syndicated in a number of black newspapers, thus keeping the players' names alive for a new generation.[16]

He was inducted into the Newark Athletic Hall of Fame in 1994.[1] In 2001, Maxwell achieved his lifelong dream by visiting the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, when he was 93 years old,[3] though he was not inducted into the Hall of Fame during his lifetime.

Death

[edit]Sherman Maxwell died on July 16, 2008, of complications of pneumonia at Chester County Hospital in West Chester, Pennsylvania.[1][3] He was 100 years old. He was survived by his sister, Berenice Maxwell Cross, of West Caldwell, New Jersey, and his son, Bruce Maxwell, of West Chester, Pennsylvania.[3] His wife, Mamie, and daughter, Lisa, had died previously.[1]

In an interview after Maxwell's death, Bob Kendrick, the director of marketing for the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Missouri said that Maxwell had been well known by Negro league players as someone who preserved records and scores that would have been lost without him.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Legendary black sportscaster Maxwell dies at 100". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. 2008-07-17. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- ^ Christine V. Baird, "Sherman Maxwell, Sportscasting Pioneer." Newark (NJ) Star-Ledger, July 17, 1998, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Weber, Bruce (2008-07-19). "Sherman L. Maxwell, 100, Sportscaster and Writer, Dies". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- ^ Jocko Maxwell. "1st Negro Sportscaster Sends Congrats." (New York City) Amsterdam News, December 11, 1954, p. 4.

- ^ a b Christine V. Baird. "Breaking Racial Barriers on Radio." Newark (NJ) Star-Ledger, October 15, 1998, p. 1.

- ^ "Bury Deejay's Mother in Evergreen Cem." (New York City) Amsterdam News, February 1, 1964, p. 26.

- ^ Christine V. Baird. "Sherman Maxwell, Sportscasting Pioneer." Newark (NJ) Star-Ledger, July 17, 208, p. 20.

- ^ "Jocko Maxwell Now Out; Broadcasts." (New York City) Amsterdam News, December 29, 1945, p. 10.

- ^ "Service Man Weds Newark Socialite." Pittsburgh Courier, June 26, 1943, p. 10.

- ^ Christine V. Baird. "Sherman Maxwell, Sportscasting Pioneer." Newark (NJ) Star-Ledger. July 17, 2008, p. 20.

- ^ "Jocko Maxwell Made Sports Director of WWRL." Chicago Defender, April 11, 1942, p. 20.

- ^ "Jocko Maxwell in Big Sportscasting Rise." Atlanta Daily World, March 30, 1942, p. 5.

- ^ Romeo L. Dougherty. "Sport Commentator Over Air." (New York City) Amsterdam News, July 9, 1934, p. 10.

- ^ "Sport Commentator Featured on WHOM." (New York City) Amsterdam News, April 21, 1934, p. 10.

- ^ "Jocko Maxwell Made Sports Director of Station WWRL." Chicago Defender, April 11, 1942, p. 20.

- ^ Jocko Maxwell. "Old-Time Negro Baseball Players – A Major League Loss." Norfolk (VA) New Journal and Guide, September 10, 1966, p. 22.

Further reading

[edit]- Clair, Michael (December 18, 2023). "Jocko Maxwell, the forgotten sports broadcasting great". MLB.com.