This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2012) |

| Shipton-on-Cherwell train crash | |

|---|---|

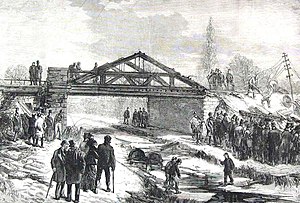

Engraving from the Illustrated London News, 1874 | |

| Details | |

| Date | 24 December 1874 ~12:30 |

| Location | Shipton-on-Cherwell, Oxfordshire |

| Country | England |

| Line | Cherwell Valley Line |

| Operator | Great Western Railway |

| Incident type | derailment |

| Cause | wheel defect |

| Statistics | |

| Trains | 1 |

| Passengers | ~260 |

| Deaths | 34 |

| Injured | 69 |

| List of UK rail accidents by year | |

The Shipton-on-Cherwell train crash was a major disaster which occurred on the Great Western Railway. It involved the derailment of a long passenger train at Shipton-on-Cherwell, near Kidlington, Oxfordshire, England, on Christmas Eve, 24 December 1874, and was one of the worst disasters on the Great Western Railway.

Colonel William Yolland of the Railway Inspectorate led the investigation and chaired the subsequent Court of Enquiry of the Board of Trade. Its report highlighted several safety problems, including wheel design, braking, and communications along trains. The accident came in a decade which saw many terrible accidents on the rail network, and which culminated in the Tay Rail Bridge disaster of 1879.

Accident

[edit]The accident happened a few hundred yards from the village of Hampton Gay and close to Shipton-on-Cherwell. The train, with 13 carriages and two engines, had left Oxford station for Birmingham Snow Hill at 11:40.[1] It was approximately 30 minutes behind schedule and travelling at about 40 miles per hour (64 km/h) when, after 6 miles (9.7 km), the tyre of the wheel on a third-class carriage broke. The carriage left the track for about 300 yards (270 m) but stayed upright, crossing a bridge over the River Cherwell.

After the bridge and before a similar bridge across the Oxford Canal, the carriage ran down an embankment, taking other carriages with it, which broke up as they crossed the field.[1] Three carriages and a goods wagon carried on over the canal bridge, and another fell into the water. The front section of the train carried on for some distance.[1]

The owner and men from the Hampton Gay paper mill close to the accident site tried to assist the injured in the snow. Telegrams were sent to local stations to summon medical help but it took an hour and a half for a doctor to appear. A special train was used to move the injured back to hospitals in Oxford.[1] At least 26 died at the scene while four others were dead by the time the special train arrived at Oxford station. At least one other died in hospital. The canal was dragged, but no bodies were found.[1]

Causes

[edit]

The basic cause was found to be a broken tyre on the carriage just behind the locomotive, but that failure was worsened by the inadequate braking system fitted to the train. When a passenger warned the fireman of the problem, by waving from the carriage window, it was still being pulled along intact between the rails. The driver braked immediately, and sounded the whistle to alert the guard in the van at the rear of the train to apply his brake, but the guard didn't hear the whistle and so there was no check on the speed of the carriages. The braking of the engine caused the leading carriage to become detached, and it left the rails completely just after crossing the Oxford Canal. It was crushed by the carriages behind as they also derailed and ran down an embankment. Others fell into the canal. There were 34 deaths, and 69 people were seriously injured in the carriages which fell from the bridge over the canal.[2]: 4

Inquiry

[edit]The inquiry that followed quickly established the root causes. The tyre was on the wheel of an old carriage and was of an obsolete design. The fracture started at a hole where a rivet attached the tyre to the wheel, possibly due to metal fatigue, although that was not specifically recognised by the inquiry. The weather was very cold that day, with freezing temperatures and snow blanketing the fields, another factor that hastened the tyre failure. The Railway Inspectorate recommended that railway companies adopt Mansell wheels, a type of wooden composite wheel, because that design had a better safety record than the alternatives. There had been a long history of failed wheels causing serious accidents, especially in the previous decade.[2]: 7–10 The problem of broken wheels was not resolved until cast steel monobloc wheels were introduced.

The disaster led to a reappraisal of braking systems and methods, and the eventual fitting of continuous automatic brakes to trains, using either the Westinghouse air brake or a vacuum brake.

The Inspectorate was also critical of the communication method between the locomotive and the rest of the train using an external cord connected to a gong on the locomotive, suggesting that a telegraphic method should be adopted instead.[2]: 11

Inquest

[edit]An inquest was opened on 26 December 1874, using the manor house at Hampton Gay. The 26 bodies found at the scene were laid out in two rows in a large paper store in the paper mill for the court to view and seek formal identification, and the wreckage was also examined.[3] The coroner and jury decided to re-convene in Oxford and permission was given to move the wreckage, but only one carriage was moved to Oxford for further examination.[3]

The following week, the coroner returned to Hampton Gay to further identify bodies, as well as those which had been kept in the third class waiting room at the Oxford Railway Station and one at Radcliffe Infirmary.[4]

Related incident

[edit]Showell's Dictionary of Birmingham, discussing the accident, notes that:[5]

In the excitement at Snow Hill Station, a young woman was pushed under a train and lost both her legs, though her life was saved, and she now has artificial limbs.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Terrible Railway Accident." Times [London, England] 25 Dec. 1874: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 1 Dec. 2013.

- ^ a b c Yolland, Col. W (27 February 1875). Report of the Court of Enquiry into the Circumstances Attending the Accident on the Great Western Railway which occurred near Shipton-on-Cherwell on the 24th December 1874. Railways Archive.

- ^ a b "The Shipton Railway Accident." Times [London, England] 28 Dec. 1874: 9. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 1 Dec. 2013.

- ^ "The Shipton Accident." Times [London, England] 29 Dec. 1874: 8. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 1 Dec. 2013.

- ^ Showell's Dictionary of Birmingham. Cornish Brothers. 1885. p. 5.

Sources and further reading

[edit]- Adams, Charles Francis (1979). "Chapter II The Angola and Shipton Accidents". Notes on Railway Accidents. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Lewis, P.R. (2007). Disaster on the Dee: Robert Stephenson's Nemesis of 1847. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. p. not cited. ISBN 978-0-7524-4266-2.

- Lewis, Peter R; Nisbet, Alistair (2008). Wheels to Disaster!: The Oxford train wreck of Christmas Eve, 1874. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7524-4512-0.

- Nisbet, Alistair F (December 2006). "The Christmas Eve Derailment". BackTrack. Easingwold: Pendragon Publishing. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- Rolt, L.T.C. (1998) [1955]. Red for Danger: the classic history of British railway disasters. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. pp. not cited. ISBN 0750920475.

- Yolland, Col. W (27 February 1875). Report of the Court of Enquiry into the Circumstances Attending the Accident on the Great Western Railway which occurred near Shipton - on - Cherwell on the 24th December 1874. Railways Archive.

External links

[edit]- "Train crash exhibition under way". BBC News. 21 December 2004. Retrieved 20 August 2012.