Smoking in Australia is restricted in enclosed public places, workplaces, in areas of public transport and near underage events, except new laws in New South Wales that ban smoking within ten metres of children's play spaces.

In particular, the most common form of smoking in Australia is tobacco smoking which is practised in a myriad of types. Data collected by the Cancer Council of Victoria and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare's National Drug Strategy Household Surveys, explicate that the majority form of tobacco in Australia that was smoked, was factory made cigarettes.[1] Likewise, a study conducted by the International Tobacco Control (ITC) established the prevalence of "Roll your own tobacco", was being utilised by 9% of the population, constituting mostly of males having a demographics of a lower level of income, and poor education.[2] Unbranded loose tobacco (chop-chop) is also smoked by smokers, sold without government taxation, being a cheaper option and therefore utilised as an alternative to factory made cigarettes.[3] 'Chop-chop' is prevalent among young Australian adults, as stated by the recent surveys conducted by the National Drug Strategy Household, which concluded that in 2016, 3.8% of smokers aged 14+ used unbranded loose tobacco. This survey also identified other forms of smoking such as the e-cigarettes being utilised by 9% of the population and finally water-pipe tobacco (shishas, hookahs and argillas).[4]

Cannabis is also another drug which is smoked rolled in a cigarette. The usage of cannabis in 2016 among the Australia population is 10.4%.[5]

History

[edit]

In the early 1700s, tobacco smoking was introduced to the north dwelling indigenous communities through the visitation of the Indonesian fishermen.[6] However, the British customs and behaviour of the utilisation of tobacco was introduced into the Australian culture in 1788,[7] due to the colonisation of Australia by the Europeans, and evidently, these tobacco related behaviours rapidly spread throughout the Aboriginal community, the free settlers and the convicts from Britain.[8] When first introduced within Australia, the supply of tobacco was restricted within the Australian community,[9] however by the 1800s tobacco was a fundamental item being used as a reward for a servants labour, or antagonistically used as a punishment for convicts, due to its addictive side effects.[1] Eventually, by 1819, 80 to 90 percent of the labour force were smokers.[1]

By the 1880s the production of cigarettes were completely mechanised, however was often chosen over dandies and larrikins.[10] More importantly, the cheapness and ease of accessibility of these manufactured cigarettes, revolutionised the way Australians smoke tobacco.[1] This cigarette was prevalent in the World War 1, as 60% of the tobacco rations donated to the trenches, were in the cigarette form. Cigarette use also rapidly increased up to 70% during World War 1, in contrast to the usage before the war.[11]

In the 1920s, societal views began to transition of women partaking in smoking behaviours and thus over the next several decades companies began to advertise smoking to women.[12] The introduction of women in the workforce, led to greater freedom of women, and hence smoking rates within Australia increased.[12]

By the 1930s the Australian Government began assisting the tobacco industry by introducing the Local Leaf Content Scheme, which required local tobacco to be used up in the manufacturing of cigarettes in Australia.[13] However, in the 1990s the Industry Commission Inquiry found that tobacco had the greatest subsidisation in agriculture within Australia, and thus the Local Leaf Content Scheme was abolished.[14] As a result, the tobacco industry within Australia declined to the oncoming threat of international competition. Currently, no commercial farming of tobacco occurs within Australia, and all tobacco products are imported from overseas.[15]

Smoking patterns in Australia

[edit]Decline in smoking

[edit]Daily tobacco smoking in Australia has been declining since 1991, where the smoking population was 24.3%.[4] Correspondingly, in 1995 23.8% of adults smoked daily. This figure also decreased in 2001, where 22.4% of the population used to smoke.[16] This constant trend of the reduction of daily smoking has continued within these past 2 decades, with 16.1% of adults smoking in 2011–12, and finally 14.5% of the population smoking daily in 2014–15, which constitutes 2.6 million adults within Australia.[16] However, most recently it was found that the smoking population of Australia in 2016 was 12.2%,[17] and thus, the smoking population in Australia has almost halved since 1991.[18]

Conversely, the rate of decline for smoking has become steady among recent years,[19] with some sources arguing that the smoking percentage within Australia did not decline between the years of 2013 and 2016.[20]

Decline of smoking in Australia from 1991 to 2016[17][18]

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Smoking prevalence in all states and territories

[edit]The daily smoking percentage in Northern Territory, has typically had the highest smoking rates within Australia.[21] The high smoking rates within Northern Territory resonates with the high percentage of Indigenous individuals living there, as the smoking prevalence of the Indigenous in 2014–15 was 39%.[22] Further, 26% of the Northern Territory population consists of individuals with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage, which is 5% less in all the other states and territories within Australia.[23] However, since 1995 Northern Territory has had the largest decrease in daily smoking rates in comparison to all other states, from 35.6% to 21% in 2014–15.[24]

| Percentages for daily smoking (%) | |

|---|---|

| New South Wales | 14 |

| Victoria | 14 |

| Queensland | 16 |

| South Australia | 13 |

| Western Australia | 14 |

| Tasmania | 18 |

| Northern Territory | 21 |

| Australian Capital Territory | 12 |

Smoking rates between males and females

[edit]The smoking percentage of men in 2016 is 16%, while the smoking percentage of women is 12%.[25] Men have consistently shown to have a higher tendency to smoke daily than women. However, daily smoking percentage for both males and females were 27.3% and 20.3% respectively in 1995, expounding a significant reduction in smoking prevalence for both genders.[1]

In 2017–18, men aged 18–24 years, around 17.5% of that age bracket smoked daily.[1] This percentage remained constant for all age groups until the age of 55–64, were the daily smoking percentage dropped to 16.5%. This figure for daily smoking, further decreased for men at the age of 75+, dropping to a percentage of 5.1%.[19]

Conversely, in 2017–18 it was found that women between the ages of 18 and 24, had a daily smoking percentage of 17.5%.[25] This figure increased to 14.7% of women between the ages of 45 and 54, and eventually decreasing to 7.5% for women between the ages of 65 and 74. Finally, this percentage further dropped to 3.7%, to women 75+.[19]

Deaths and health related risk factors caused by smoking in Australia

[edit]

Smoking is the direct cause of the greatest number of preventable deaths in Australia,[26] with a death toll of 15,500 every year.[27] Smoking has a causative association with a myriad of other types of diseases, such as heart disease, diabetes, stroke and different forms of cancers. In particular, cancers were found to be the leading cause of tobacco-related deaths.[28] Of all deaths caused by smoking in Australia,Lung cancer is the most common cause.[29] In 2003, tobacco was found to be responsible for 7.8% of disease and injury that occurred within Australia.[30]

| Disease | Percentage of total burden attributable to tobacco |

|---|---|

| Lung cancer | 30.6 |

| COPD | 29.7 |

| Coronary heart disease | 12.4 |

| Stroke | 3.9 |

| Oesophageal cancer | 3.2 |

| Asthma | 2.6 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 2.6 |

| Mouth and pharyngeal cancer | 2 |

| Bowel cancer | 1.8 |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 1.6 |

| Liver cancer | 1.5 |

| Bladder cancer | 1.4 |

| Diabetes | 0.9 |

| Atrial fibrillation and flutter | 0.9 |

| Leukaemia | 0.8 |

| Stomach cancer | 0.8 |

| Kidney cancer | 0.8 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 0.7 |

| Other respiratory disease | 0.7 |

| Aortic aneurysm | 0.5 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.2 |

| Hypertensive heart disease | 0.2 |

| Cervical cancer | 0.2 |

| Lower respiratory infections | 0.1 |

| Tuberculosis | 0.0 |

| Influenza | 0.0 |

| Otitis media | 0.0 |

Underage smoking

[edit]Smoking prevalence of underage adults

[edit]The smoking prevalence of underage adults in Australia has oscillated over time.[31] During the 1980s, smoking rates among young adults began to decrease, but increased during the early 1990s, while finally in the 1996, this percentage began to decrease again.[1][31] Most recently, in 2017, the underage smoking population in Australia was found to be lowest ever recorded.[1]

The downward trend of the reduction of smoking amongst underage individuals from the late 1990s, was accompanied with the introduction of the National Tobacco Campaign.[32] Although failing, to reduce the smoking prevalence amongst adults within Australia,[33] the campaign proved to be a success in reducing smoke rates amongst young adults.[34] Factors such tobacco taxes and stricter laws to restrict tobacco sales to minors, also played a huge role in decreasing the smoking prevalence amongst the youth.[35] Likewise, the decline in smoking rates from 2011 to 2014 came in light of the establishment of the National Tobacco Strategy[36] in 2012, and a myriad of other factors such as the new plain packaging laws, and introducing more smoke free environments.[37] The slow decline of smoking rates among underage individuals, in recent years can be from a result of less government funded media campaigns and the introduction of new tobacco products within Australia, that entice young adults to smoke.[38]

Smoking percentage of young adults between 16 and 17 that smoked in the past week[39]

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Smoking percentage of young adults between 12 and 15 that smoked in the past week[39]

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Accessibility of cigarettes to young adults

[edit]In 1996, it was found that 35% of males and 40% of females aged 12–17, most commonly obtained cigarettes through their friends.[40] This way of young adults accessing cigarettes remained as the main source of cigarette accessibility for males, whilst decreasing with age for females.[1] Nonetheless, for male and female young adults between the ages of 16 and 17, the primary source of cigarette accessibility was through illegal purchases in stores, as 45% of females and 55% of males in this age category reported to have purchased their own cigarettes.[41]

The second most frequent way that young adults between the ages of 12 and 15 acquired cigarettes was from older individuals who obtained the cigarettes for them.[40]

Underage Australian students who participated in smoking purchased cigarettes most commonly from outlets such as retail markets and service stations.[42] It was found that 29% of smokers aged 12 obtained cigarettes from vending machines, in comparison to 5% of older teenagers who obtained cigarettes in this manner.[43]

The purchase of single cigarettes was also a common way that underage smokers obtained cigarettes, with 21% of males and 12% of females purchasing single cigarettes regardless of the illegality of individual sale.[40] Rates of purchase of individual cigarettes decreases as the purchaser's age increases, with 29% of 12 year old smokers reporting purchase of single cigarettes in comparison to 5% of individuals between 16 and 17 years of age purchasing single cigarettes.[1]

| Percentage of high school students (%) | |

|---|---|

| Electronic cigarettes | 20.8 |

| Cigarettes | 8.1 |

| Cigar | 7.6 |

| Smokeless tobacco | 5.9 |

| Hookahs | 4.1 |

| Pipe tobacco | 1.1 |

Underage smoking laws

[edit]Western Australia

[edit]

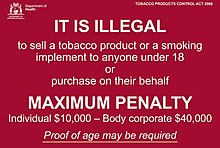

The Tobacco Products Control Act (2006), prohibits the sale and supply of cigarettes to minors.[44] The power to monitor and enforce this act lies with the Health Department of Western Australia.[45] This department aims to reduce children's access to tobacco by investigating possible breaches of this act and increasing community aid to educate minors.[40]

New South Wales

[edit]New South Wales has adopted a comprehensive program following the amendments to the Public Health Act 1991, in 1996, due to the rising rate of underage smoking, and their ease in accessing tobacco products.[40] This program ensured that tobacco retailers asked for identification to ensure that customers were above the age of 18, and finally an educational strategy to increase general awareness about the requirements legislated under the Public Health Act 1991.[46] The responsibility of monitoring the compliance of the Public Health Act 1991, falls with the Environmental Health Officers, who prosecute retailers when this legislation is breached.[47]

South Australia

[edit]The measures implemented by South Australia to prevent and minimise the supply of tobacco to underage individuals are enacted through the Tobacco and E-Cigarette Products Act 1977 (the Tobacco Product Regulation Act 1997 prior to 31 March 2019), which ultimately increased penalties for breaches of legislation.[48]

Victoria

[edit]Underage access to tobacco in Victoria is handled through a combination of domestic laws and local projects.[40] The Tobacco Act 1987, makes it illegal for tobacco retailers in Victoria to sell tobacco products to individuals under the age of 18.[49] Educational programs run by QUIT Victoria, assists in informing retailers and making them aware about legislative issues.[50] The amendments to the Tobacco Act 1987, that have been passed recently has also increased the fines for violation of tobacco laws.[40] Unlike other states there is no current statewide compliance program.[40] However, a high number of councils within Victoria undertake their own compliance testing as the Department of Health and Human Services provides a password protected, educational and enforcement resources online, to assist them in understanding the obligations set by The Tobacco Act 1987, and therefore enforcing and ensuring retailers are compliant.[51]

Tasmania

[edit]The smoking age in Tasmania was raised up to 18 years of age in February 1997, to tackle the increasing rates of underage smoking within the state.[40] The provisions that separated tobacco from confectionery in Tasmania were introduced through the enactment of the Public Health Act 1977.[40] This legislation also allows the government to prosecute retailers or seize tobacco products from underage individuals who are found to be smoking.[52] However, Tasmanian laws doesn't require the identification of age as the only justification to sell tobacco to individuals under the age of 18, as is the circumstance in some states.[53]

Northern Territory

[edit]Between the period of 1996 and 1997, compliance surveys of retailers were conducted throughout Northern Territory, which concluded that 22% of tobacco retailers were fine with selling tobacco products to customers of the age of 15.[40] Due to these results, from 1996 to 1999, educational campaigns were introduced to educate retailers of their responsibilities and ensure that they comply with the Tobacco Act.[40]

The Tobacco Control Act 2002 outlaws the supply of tobacco products to individuals under the age of 18.[54] This act was amended in 2019, coming into effect on 1 July 2019, which legislated that tobacco vending machines will not be allowed to be placed in a liquor licensed area, were an individual under the age of 18 can enter and easily access it.[55]

Future plans to stop underage smoking in Northern Territory, includes The Tobacco Action Plan 2019–2023, which aims to acknowledge the standards under the National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health (NPAPH) and ultimately control tobacco supply to children under the age of 18, by implementing distinctive activities to improve underage smoking rates in Northern Territory.[56]

Queensland

[edit]Due to the increasing underage smoking rates in Queensland, the Queensland Tobacco Products (Prevention of Supply to Children) Act 1998 was introduced, raising the legal age of purchasing tobacco from 16 to 18 years old of age.[40] The Queensland government also provides training to employees who work at tobacco retailers to ensure that underage individuals can't purchase tobacco from there.[57]

| Western Australia | New South Wales | South Australia | Victoria | Tasmania | Northern Territory | Queensland | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legislation preventing sales to minors | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Legislation preventing supply to minors | YES | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Legislation regulating the possession of tobacco by a minor | NO | NO | NO | YES | NO | NO | NO |

| Defence about proof of age | NO | YES | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Monitoring the compliance of measures | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | NO |

| Legal proceedings | 57 | 121 | 2 | 11 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Selling | 50 | 121 | 2 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Supplying | 7 | nil | nil | nil | 1 | nil | nil |

Tobacco-controlling campaigns

[edit]The National Campaign against drug abuse

[edit]In 1995, the Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy (MCDS) was created, consisting of a myriad of political leaders and ministers all around Australia.[58] The MCDS introduced the National Campaign Against Drug Abuse, later renamed as the National Drug Strategy.[59]

In 1990, the National Campaign Against Drug Abuse, launched a $2 million advertisement, 'Smoking - who needs it?', which was aimed at young girls.[60] This advertisement followed an increase in the percentage of young women adults wanting to reduce their daily smoking rates.[61]

The National Tobacco Campaign

[edit]In 1997, a nationwide campaign was introduced, involving all the Quit campaigns in all states and territories, and the Commonwealth of Australia.[1]

During the initial phase of The National Tobacco Campaign $4.5 million was allocated to the campaign for advertising, while the Quit campaigns around Australia contributed $3.29 million.[62] It was concluded that during this period the National Tobacco Campaign decreased the smoking prevalence within Australia by 1.4%, with an estimated reduction by 10,000 in lung cancer diagnoses, and an estimated reduction in the number of smoking-related strokes by 2,500.[62][63] It was also found that this campaign allowed 55,000 deaths to be avoided.[63]

The advertising conducted by this campaign essentially focused on smokers between the ages of 18 and 40, and was considered highly successful due to co-operation between state governments, federal governments, and focus groups.[40] The advertisements recognised that smokers could be encouraged to give up smoking by accentuating that in ceasing tobacco use, ex-smokers gain more from the act than they sacrifice.[64]

The campaign introduced 6 media campaigns (entitled 'Artery', 'Lung', 'Tumour', 'Brain', 'Eye' and 'Tar') between the years of 1997 and 2000, intending to appeal to people of lower socioeconomic status by illustrating that individuals in this cross section of society had the highest smoking rates and suffered the highest levels of smoking related disease.[65]

Cigarette packaging

[edit]During 2006 new regulations for packaging of tobacco products were introduced, consisting of graphical warnings about the consequences of smoking.[62] Since March 2006, items containing tobacco which were imported for sale or manufactured within Australia need to display the confronting images, warning individuals about the dangers of smoking.[66]

Similarly, legislation requiring plain packaging was enacted through the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 and the Tobacco Plain Packaging Regulations 2011, which stipulate the use of a particular colour (Pantone 448C), typeface and font sizes, presence and specification of an image depicting disease, and material type and package construction for tobacco products.[67]

Australia's packaging specifications for tobacco and tobacco-relate products are outlined under the Competition and Consumer (Tobacco) Information Standard (2011), which requires that graphical images about the negative effects of smoking on the body must cover 75% of the front and 90% of the back of a cigarette packet. The standard also states that these images must also cover 75% of the back of non-tobacco smoking products.[68]

The intention of implementing plain packaging and requiring the use of an unappealing packet colour, and preventing the use of graphical and stylistic elements to differentiate between brands is to reduce the appeal of tobacco products, and to eliminate packaging as a form of promotion or advertising for the product. Plain packaging also prevents the use of misleading terms, and reduces subsequent erroneous beliefs held by smokers.[69]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Winstanley, Margaret (2015). "Tobacco in Australia". Cancer Council Victoria.

- ^ O’Connnor, R. J.; Yong, H.-H.; Devlin, E.; Cummings, K. M.; Hammond, D.; Borland, R.; Young, D. (1 June 2006). "Prevalence and attributes of roll-your-own smokers in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey". Tobacco Control. 15 (suppl 3): iii76–iii82. doi:10.1136/tc.2005.013268. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 2593057. PMID 16754951.

- ^ "Administration of Tobacco Excise". www.anao.gov.au. 26 January 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b "National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "Alcohol, tobacco & other drugs in Australia, Cannabis". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ Brady, Maggie (2002). "Health Inequalities: Historical and cultural roots of tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 26 (2): 120–124. doi:10.1111/j.1467-842X.2002.tb00903.x. ISSN 1753-6405. PMID 12054329.

- ^ Walker, R. B. (1984). Under fire : a history of tobacco smoking in Australia. Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0522842798. OCLC 13328911.

- ^ Jankowiak, William R.; Bradburd, Daniel (2003). Drugs, labor, and colonial expansion. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0816523517. OCLC 52055786.

- ^ Walker, R. B. (1 October 1980). "Tobacco smoking in Australia, 1788–1914". Historical Studies. 19 (75): 267–285. doi:10.1080/10314618008595638. ISSN 0018-2559.

- ^ Read "Ending the Tobacco Problem: A Blueprint for the Nation" at NAP.edu. 2007. doi:10.17226/11795. ISBN 978-0-309-10382-4.

- ^ "Smoking in the First World War". Centenary of WW1 in Orange. 4 July 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ a b Haglund, Margaretha; Amos, Amanda (1 March 2000). "From social taboo to "torch of freedom": the marketing of cigarettes to women". Tobacco Control. 9 (1): 3–8. doi:10.1136/tc.9.1.3. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 1748294. PMID 10691743.

- ^ "The Tobacco Growing and Manufacturing Industries – Industry Commission Inquiry Report". www.pc.gov.au. 29 June 1994. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ "The Tobacco Growing and Manufacturing Industries" (PDF). Industry Commission. 1994.

- ^ "Tobacco". myVMC. 3 August 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Kalisch, David W (2015). "National Health Survey" (PDF). Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ a b "Alcohol, tobacco & other drugs in Australia, Introduction". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Smoking rates". www.quit.org.au. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ a b c "Main Features – Smoking". www.abs.gov.au. 7 February 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Australian Institute of Health and Welfare". AIHW.

- ^ "Northern Territory misses an opportunity to reduce smoking rates". ATHRA. 27 November 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "Details – Key findings". www.abs.gov.au. 28 April 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Main Features – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Population Data Summary". www.abs.gov.au. 28 June 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Main Features – Smoking". www.abs.gov.au. 7 February 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Smoking statistics". www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "quitnow – Smoking – A Leading Cause of Death". www.quitnow.gov.au. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ "Smoking and tobacco control – Cancer Council Australia". www.cancer.org.au. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Smoking statistics". www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Better Health Victoria". Better Health.

- ^ "Main Features – Smoking". www.abs.gov.au. 8 December 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Adolescents and Tobacco: Trends". HHS.gov. 23 September 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "NLA Australian Government Web Archive". webarchive.nla.gov.au. Archived from the original on 1 August 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ "NLA Australian Government Web Archive". webarchive.nla.gov.au. Archived from the original on 1 August 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ Hill, David; White, Victoria; Effendi, Yuksel (2002). "Measuring Prevalence: Changes in the use of tobacco among Australian secondary students: results of the 1999 prevalence study and comparisons with earlier years". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 26 (2): 156–163. doi:10.1111/j.1467-842X.2002.tb00910.x. ISSN 1753-6405. PMID 12054336.

- ^ "National Drug Strategy – National Drug Strategy". www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ "National Tobacco Strategy 2012–2018". www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ "Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011". www.legislation.gov.au. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ "Tobacco in Australia: time to get back to basics". InsightPlus. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ a b Guerin, Nicola. "Australian Secondary School Students' Use of Tobacco, Alcohol, Over the-counter Drugs, and Illicit Substances". Cancer Council Victoria.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o 1. Overview of young people's access to tobacco products, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, retrieved 7 June 2019

- ^ Hill, David; White, Victoria; Letcher, Tessa (1999). "Tobacco use among Australian secondary students in 1996". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 23 (3): 252–259. doi:10.1111/j.1467-842X.1999.tb01252.x. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30096569. ISSN 1753-6405. PMID 10388168.

- ^ Freeman, Becky (2014). "Evidence of the impact of tobacco retail policy initiatives" (PDF). Health NSW.

- ^ a b "Youth and Tobacco Use". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 February 2019. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ "Western Australian Legislation – Tobacco Products Control Act 2006". www.legislation.wa.gov.au. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "Tobacco control legislation in Western Australia". ww2.health.wa.gov.au. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "NSW Legislation". legislation.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "REVIEW OF THE Public Health Act 1991" (PDF). NSW Health Department.

- ^ "Smoking, the rules and regulations :: SA Health". www.sahealth.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ "Victorias tobacco laws". www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Information for professionals". www.quit.org.au. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Councils – tobacco reform". www2.health.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Public Health Act and Associated Guidelines". www.dhhs.tas.gov.au. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "View – Tasmanian Legislation Online". www.legislation.tas.gov.au. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Legislation Database". legislation.nt.gov.au. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "Tobacco". health.nt.gov.au. 15 December 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Northern Territory Tobacco Action Plan 2019–2023". digitallibrary.health.nt.gov.au. 29 May 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Tobacco retailing | Tobacco laws in Queensland". www.health.qld.gov.au. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "National Drug Strategy 2010–2015 A framework for action on alcohol, tobacco and other drugs" (PDF). National Drug Strategy. 2011.

- ^ National Campaign Against Drug Abuse. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. 1985. ISBN 9780644043014.

- ^ Crofton, J (1 July 1990). "The Seventh World Conference on Tobacco and Health". Thorax. 45 (7): 560–562. doi:10.1136/thx.45.7.560. ISSN 0040-6376. PMC 462589. PMID 2396235.

- ^ "Offensive Market Research", Offensive Marketing, Elsevier, 2004, pp. 323–345, doi:10.1016/b978-0-7506-7459-1.50016-3, ISBN 9780750674591

- ^ a b c "How to quit smoking". Australian Government Department of Health. 27 March 2019. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ a b Matthews, J. P.; Hurley, S. F. (1 December 2008). "Cost-effectiveness of the Australian National Tobacco Campaign". Tobacco Control. 17 (6): 379–384. doi:10.1136/tc.2008.025213. hdl:10072/22388. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 18719075. S2CID 10634585.

- ^ Carroll, T.; Hill, D. (1 September 2003). "Australia's National Tobacco Campaign". Tobacco Control. 12 (suppl 2): ii9–ii14. doi:10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii9. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 1766100. PMID 12878768.

- ^ "Preventing Chronic Disease: A Strategic Framework" (PDF). Health Victoria. 2001.

- ^ "Health Warnings". The Department of Health. 2018.

- ^ Introduction of tobacco plain packaging in Australia, Australian Government Department of Health, retrieved 9 June 2019

- ^ "WHO | Plain packaging of tobacco products: evidence, design and implementation". WHO. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ "Plain packaging of tobacco products: evidence, design and implementation". World Health Organization. 30 May 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Lillard, Dean R. and Rebekka Christopoulo, eds. Life-Course Smoking Behavior: Patterns and National Context in Ten Countries (Oxford University Press, 2015); covers Australia, Canada, and UK among others.

- Walker, R. Under Fire: A History of Tobacco Smoking in Australia. (Melbourne University Press, 1984).

- Walker, R. B. "Tobacco smoking in Australia, 1788–1914". Historical Studies (1980). 19 (75): 267–285. doi:10.1080/10314618008595638. ISSN 0018-2559.

- Winstanley, M., S. Woodward, and N. Walker. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and Issues (2nd ed. 1995).