This article needs to be updated. (October 2012) |

The Spanish National Health System (Spanish: Sistema Nacional de Salud, SNS) is the agglomeration of public healthcare services that has existed in Spain since it was established through and structured by the Ley General de Sanidad (the "Health General Law") of 1986. Management of these services has been progressively transferred to the distinct autonomous communities of Spain, while some continue to be operated by the National Institute of Health Management (Instituto Nacional de Gestión Sanitaria, INGESA), part of the Ministry of Health and Social Policy (which superseded the Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs—Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo—in 2009). The activity of these services is harmonized by the Interterritorial Council of the Spanish National Health Service (Consejo Interterritorial del Servicio Nacional de Salud de España, CISNS) in order to give cohesion to the system and to guarantee the rights of citizens throughout Spain.

Article 46 of the Ley General de Sanidad establishes the fundamental characteristics of the SNS:

- a. Extension of services to the entire population.

- b. Adequate organization to provide comprehensive health care, including promotion of health, prevention of disease, treatment and rehabilitation.

- c. Coordination and, as needed, integration of all public health resources into a single system.

- d. Financing of the obligations derived from this law will be met by resources of public administration, contributions and fees for the provision of certain services.

- e. The provision of a comprehensive health care, seeking high standards, properly evaluated and controlled.[1]

Antecedents to the SNS in Spain

[edit]Public intervention in collective health problems has always been of interest to governments and societies, especially in the control of epidemics through the establishment of naval quarantines, the closing of city walls and prohibitions on travel in times of plague, but also in terms of hygienic and palliative measures. Al-Andalus—Muslim-ruled medieval Spain—was distinguished by its level of medical knowledge relative to the rest of Europe, particularly among the physicians of the Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain. In the years after the Reconquista, the Real Tribunal del Protomedicato regulated the practice of medicine in Spain and in its colonies. However, the system of medical faculties at the various universities was very decentralized. Surgery and pharmacy were quite separate from medicine and were considerably less prestigious; the systems of Galen and Hippocrates dominated medical practice during most of the era of the Antiguo Régimen.

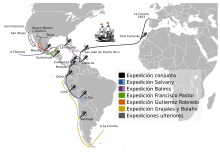

Medicine was one of the principal fields of activity for the novatores of the late 17th century, but their initiatives were individualized and localized. There is some continuity from their work to the broader work during the Age of Enlightenment, such as through the Colegio de Cirugía de San Carlos ("San Carlos College of Surgery") in Madrid. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Balmis Expedition (1803) to administer the smallpox vaccine throughout the Spanish colonies was a public health undertaking of unprecedented geographical scope.

The Cortes of Cádiz debated a sanitary code (the Código Sanitario de 1812), but nothing was approved due to lack of scientific and technical consensus about the actions to be undertaken. During the bienio progresista, the Law of 28 November 1855 established the basis for a General Health Directorate (Dirección General de Sanidad), which was created a few years later and which would last into the 20th century. The Royal Decree of 12 January 1904 approved the General Health Instruction (Instrucción General de Sanidad), which altered little of the 1855 scheme besides the name; the name would later change to General Inspectorate of Health (Inspección General de Sanidad).

After the Spanish Civil War, the Ley de Bases de 1944 perpetuated this . The Law of 14 December 1942 create a system of obligatory health insurance under the already extant National Insurance Institute (Instituto Nacional de Previsión, INP). The system was based on a percentage tax linked to employment. This was further modified by the General Law of Social Security (Ley General de la Seguridad Social) in 1974, toward the end of the Franco regime.[2] Social Security had taken on an increasing number of diseases within its package of services, as well as covering a larger number of individuals and communities.

The General Health Law (Ley General de Sanidad) of 25 April 1986 and the creation of Health Councils (Consejerías de Sanidad) and a Ministry of Health, fulfilled the mandate of the Spanish Constitution of 1978, in particular Articles 43 and 49 which made protection of health a right of all citizens, and Title VIII, which foresaw that purview over matters of health would devolve to the autonomous communities.[3]

Laws

[edit]The General Health Law of 1986

[edit]The General Health Law of 1986 (Ley 14/1986 General de Sanidad) was formulated on two bases. First, it carries out a mandate of the Spanish Constitution, whose articles 43 and 49 establish the right of all citizens to protection of their health. The law recognizes a right to health services for all citizens and for foreigners resident in Spain.

Second, Title VIII of the Constitution confers upon the autonomous communities broad purview in matters of health and health care. The autonomous communities have first-order importance in this area, and the law permits devolution of these functions from the central government to the autonomous communities, in order to provide a health care system sufficient for the needs of their respective jurisdictions. Article 149.1.16 or the Constitution, a further basis for the present law, establishes substantive principles and criteria that allow general and common characteristics to be consistent throughout the new system, providing a common basis for health services throughout Spanish territory.

The administrative device set up by the law is the National Health System. The presumption underlying the adopted model is that in each autonomous community, authorities are adequately equipped with necessary territorial perspective, so that the benefits of autonomy do not conflict with the needs of management efficiency.

The National Health System is thus conceived as the set of health services of the Autonomous Communities properly coordinated.[4]

Thus, the various health services fall under the responsibility of the respective autonomous communities, but also under basic direction and coordination by the central state. The respective health services of the autonomous communities would gradually realize a transfer of health resources from the central government to the autonomous communities.

La ley 15/97 “Nuevas Formas de Gestión”

[edit]The law of 1997 allowed private health care companies to enter the market. It has been argued to be the beginning of deregulation.[5]

Law of Cohesion and Quality, 2003

[edit]The General Health Law was complemented in 2003 by the Law of Cohesion and Quality of the National Health System (Ley 16/2003 de cohesión y calidad del Sistema Nacional de Salud), which maintained the basic lines of the General Health Law, but modified and broadened the articulation of that law to reflect existent social and political reality. By 2003, all of the autonomous communities had gradually assumed purview in matters of health and had established stable models to finance the assumed purview. Meanwhile, in the 17 years since the original law, Spanish society had undergone many cultural, technological and socioeconomic changes that affected people's ways of life and affected the country's patterns of disease and illness. These posed new challenges to the National Health System.

Therefore, the 2003 law establishes coordination and cooperation of public health authorities as a means to ensure citizens the right to health protection, with the common goal of ensuring equity, quality and social participation National Health System. The law defines a core set of functions common to all of the autonomous health services. Without interfering with the diversity of forms of organization, management and services inherent in a decentralized system, it attempts to establish certain basic, common safeguards throughout the country. This law attempts to establish collaboration of public health authorities with respect to benefits provided, pharmacy, health professionals, research, health information systems, and the overall quality of the health system.

Toward these ends, the law created or empowered several specialized organs and agencies, all of which are open to the participation of the autonomous communities. Among these are the Agency of Evaluation of Technologies (Agencia de Evaluación de Tecnologías, Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios), the Human Resources Committee (Comisión de Recursos Humanos), the Committee to Assess Health Research (Comisión Asesora de Investigación en Salud), the Charles III Institute of Health (Instituto de Salud Carlos III), the Institute of Health Information (Instituto de Información Sanitaria), the Quality Agency of the National Health System (Agencia de Calidad del Sistema Nacional de Salud) and the Observatory of the National Health System (Observatorio del Sistema Nacional de Salud).

The basic organ of cohesion is the Interterritorial Council of the Spanish National Health Service (Consejo Interterritorial del Servicio Nacional de Salud de España), which has great flexibility in decision making, as well as mechanisms to build consensus and to bring together the parties taking such decisions. A system of inspection, the Alta Inspección, assures that accords are followed.[6]

Royal Decree-Law of 2012

[edit]The Royal Decree-Law 16/2012[7] was introduced on April 20, 2012. It puts into law severe cuts in the Spanish National Health System, including the following:

- Refusal to give assistance to unregistered foreigners (in effect from September 1, 2012). This hasn't been applied by all the comunidades autónomas.

- Increase of the percentage of medicines paid by the user:[8]

- Senior citizens didn't pay for medicines before the reform, but now they pay 10% (limited to €8/month if their income is ≤€18,000 a year, €18/month if their income is >€18,000 and ≤€100,000 a year, or €60/month if their income is >€100,000 a year).

- Workers now pay 40% if their income is ≤€18,000 a year, 50% if their income is >€18,000 and ≤€100,000 a year, or 60% if their income is >€100,000 a year.

Governing agencies

[edit]Ministry of Health and Social Policy

[edit]

The Ministry of Health and Social Policy develops the policies of the Government of Spain in matters of health, in planning and delivery of services, as well as exercising the purview of the General Administration of the State to assure citizens the right to protection of their health. The ministry has its headquarters on the Paseo del Prado in Madrid, across the street from the Museo del Prado.

The Royal Decree 1041/2009 of 29 June lays out the basic organic structure of the Spanish Ministry of Health and Social Policy. From the date of that decree, the new ministry assumed the functions of, and superseded the former Ministry of Health and Consumption (Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo) and Secretary of State for Social Policy, Family, and Attention to Dependency and Disability (Secretaría de Estado de Política Social, Familia y Atención a la Dependencia y a la Discapacidad).

The objective of this reorganization is to reinforce the role of the single ministry as the instrument of cohesion for the National Health System (SNS), adding to the portfolio of the Secretary General of Health purview in matters of the quality of the SNS by adding to it the Agency of Quality of the National Health System (Agencia de Calidad del Sistema Nacional de Salud) and the General Directorate of Advanced Therapies and Transplants (Dirección General de Terapias Avanzadas y Trasplantes).[9]

Interterritorial Council

[edit]

The General Health Law of 1986 created the Interterritorial Council of the Spanish National Health Service (Consejo Interterritorial del Servicio Nacional de Salud, CISNS) as the organ of general coordination in matters related to health between the central State and the autonomous communities who were given authority in health matters under that law. It is jointly composed, and coordinates the basic lines of health policy in matters affecting contracts; acquisition of health and pharmaceutical products, as well as other related goods and services; as well as basic health personnel policies.

The 2003 Law of Cohesion and Quality of the SNS introduced significant changes in the composition, functioning, and purview of the CISNS. Under this law, the CISNS functions variously as a plenary body, by delegated committees, through technical commissions, and through work groups. It meets as a plenary body at the initiative of its president or at the initiative of one-third of its members; plenary meetings occur at least four times a year. To some extent, this is a formality: resolutions from CISNS commissions are typically adopted by consensus. Cooperation agreements to conduct joint health actions are formalized in CISNS agreements.

Under the Law of Cohesion, CISNS functions mainly through the adoption of and compliance with joint accords, through the political use of the plenary sessions, with each member making an uncompromising defense of the interests of its region.

Presentations, committees, and working groups have been very important, some more than others. Important committees include:[10]

- Public Health Committee (Comisión de Salud Pública)

- Permanent pharmacy committee (Comisión permanente de farmacia)

- Scientific-technical committee of the National Health System (Comisión científico-técnica del sistema Nacional de Salud)

- Committee to monitor the health cohesion fund (Comisión de seguimiento del fondo de cohesión sanitaria)

- Permanent committee on insurance, funding, and benefits (Comisión permanente de aseguramiento, financiación y prestaciones)

- Committee against gender violence (Comisión contra la violencia de género)

- Transplant committee (Comisión de trasplantes)

Articles 69, 70 and 71 of the Law of Cohesion regulate the principal functions of the Interterritorial Council of the SNS. The principal aspects of the Interterritorial Council are:

The Interterritorial Council is constituted by the Minister of Health and Consumer Affairs [now of Health and Social Policy], who holds its presidency, and by the Councilors with purview over matters of health of the autonomous communities. The vicepresidency of the body will be fulfilled by one of the Councilors with purview over matters of health of the autonomous communities, elected by all of the Councilors who make up the body.[11]

The CISNS will come to know, debate among other things, and, as appropriate, make recommendations on the following matters:

- a) The development of the portfolio of services corresponding to the Catalog of Services of the National Health System, as well as its actualization.

- b) The establishment of health services complementary to the basic services of the National Health System on the part of the autonomous communities.

- c) Minimal guarantees of safety and quality for the authorization of the opening and placing into function of the health centers, services and establishments.

- d) The general and common criteria for the development of collaboration between pharmacy offices.

- e) The basic criteria and conditions of the convocations of professionals to assure their mobility throughout the State.

- f) Declaration of the necessity to realize coordinated actions in matters of public health to which this law refers.

- g) General criteria for the public financing of medicines, medical products and their variables.

- h) Establishment of criteria and mechanisms in order to guarantee at all times the financial sufficiency of the system.

The prior functions shall be exercised without prejudice to the legislative purview of the Cortes Generales and, as appropriate, the norms of the General Administration of the State; likewise the normal developmental, executive and organizational purview of the autonomous communities.[12]

Purview of the autonomous communities

[edit]Article 41 of the General Health Law establishes that:

- The autonomous communities exercise the purview assumed in their statutes [of autonomy] and those that the state transfers to them or, as appropriate, delegates to them.

- The public policies and actions foreseen in this Act which are not expressly reserved for the state will be deemed to have been delegated to the autonomous communities.[13]

The State finances, through general taxes, all health benefits and a percentage of pharmaceutical benefits. This tax is shared among the several autonomous communities according to various sharing criteria now that the communities are responsible for health in their respective territories.

Each year the CISNS, after deliberation, establishes the portfolio of services covered by the National Health System, which is published by a Royal Decree of the Ministry of Health. Each autonomous community then establishes its respective portfolio of services, which includes at least the service portfolio of the National Health System.

Purview of local governments

[edit]

Article 42 of the General Health Law sets out that ayuntamientos—municipal governments—have the following responsibilities with respect to health, without prejudice to the purview of other public administrative bodies:

- a) Health control of the environment: air pollution, water supply [and water quality], wastewater treatment, urban and industrial residue.

- b) Health control of industries, activities and services, transport, noise and vibrations.

- c) Health control of buildings and places of human residence or gathering, especially of food centers, hairdressers, saunas and centers of personal hygiene, hotels and residential centers, schools, tourist campsites and areas of physical activity for sports and recreation.

- d) Health control of perishable food distribution and supply, beverages and other products directly or indirectly related to human use or consumption, such as means of transport.

- e) Health control of cemeteries and mortuary health policy.[14]

Territorial organization

[edit]As a consequence of the decentralization contemplated by the Spanish Constitution, each autonomous community has received adequate transfers to create a health service, the administrative structure that manages all of the centers, services and establishments of the community itself, as well as its deputations, municipal governments, and whatever other territorial administrations fall within that community. The Law of Cohesion establishes the Interterritorial Council (CISNS) as the organ of coordination and cooperation of the SNS.

In the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla the corresponding health services are provided by the National Institute of Health Management, INGESA.

| Autonomous community | Royal Decree constituting the Autonomic Health Service[15] | Identification of the Autonomic Health Service | Logo | Population served[16] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1517/1981, 8 July | Servei Català de Salut (CatSalut) | 7,467,423 | ||

| 400/1984, 22 February | Servicio Andaluz de Salud (SAS) |

|

8,285,692 | |

| 1536/1987, 6 November | Osakidetza | 2,155,546 | ||

| 1612/1987, 27 November | Agència Valenciana de Salut |

|

5,094,675 | |

| 1679/1990, 28 December | Servizo Galego de Saúde (SERGAS) | 2,794,796 | ||

| 1680/1990, 28 December | Servicio Navarro de Salud-Osasunbidea | 629,569 | ||

| 446/1994, 11 March | Servicio Canario de la Salud (SCS) |

|

2,075,968 | |

| 1471/2001, 27 December | Servicio de Salud del Principado de Asturias (SESPA) | 1,085,289 | ||

| 1471/2001, 27 December | Servicio Cántabro de Salud (SCS) | 582,138 | ||

| 1473/2001, 27 December | Servicio Riojano de Salud | 321,702 | ||

| 1474/2001, 27 December | Servicio Murciano de Salud (SMS) |

|

436,870 | |

| 1475/2001, 27 December | Servicio Aragonés de Salud (SALUD) |

|

1,326,918 | |

| 1476/2001, 27 December | Servicio de Salud de Castilla-La Mancha (SESCAM) |

|

2,081,313 | |

| 1477/2001, 27 December | Servicio Extremeño de Salud (SES) |

|

1,102,410 | |

| 1478/2001, 27 December | Servei de Salut de les Illes Balears (IB-SALUT) |

|

1,071,221ae | |

| 1479/2001, 27 December | Servicio Madrileño de Salud (SERMAS) |

|

6,271,638 | |

| 1480/2001, 27 December | Sanidad Castilla y León (SACYL) |

|

2,553,301 |

Health coverage in Spain

[edit]Under Chapter III of the 1978 Spanish Constitution, all Spanish citizens are beneficiaries of public health services. Concretely, it establishes that:

- Article 39: The public powers assure social, economic and juridical protection of the family.

- Article 43: The right to health protection is recognized. It is the responsibility of public authorities to organize and act as guardian over public health through preventive measures and the provision of necessary services. The Law will establish the rights and duties of all in this respect. The public powers will promote health education, physical education and sports.

- Article 49. The public powers will bring into existence a policy of prevention, treatment, rehabilitation and integration of those with physical, sensory or psychological disabilities.[17]

Further, the Organic Law 4/2000 (Ley Orgánica 4/2000) establishes the rights and liberties of foreigners resident in Spain. Its effect on the healthcare provision can be seen in the following articles:

- Article 3. Foreigners will enjoy in Spain, in equal conditions with the Spanish, the rights and liberties recognized in Title I of the Constitution and in the laws that develop it, in terms established in this Organic Law.

- Article 10. Foreigners will have the right to engage in remunerated activity in self-employment or working for others, such as access to the Social Security System, in terms foreseen in this Organic Law and in the dispositions that develop it.

- Article 12. Foreigners who are registered in Spain in the municipality in which they are habitually resident have the right to health services on the same conditions as the Spanish. Foreigners who are in Spain have the right to urgent health services in the event of contracting severe illness or having an accident, whatever may be the cause, and the continuity of this care until the time of discharge. Foreign minors of less than 18 years who are in Spain have the right to health care on the same conditions as the Spanish. Pregnant foreigners who are in Spain have the right to health care during the pregnancy, while giving birth, and post partum.[18]

Financing

[edit]Article 10 of the Law of Cohesion establishes that the financing of the Spanish health system is the responsibility of the autonomous communities in conformity with the accords of transfer and the current system of autonomic financing, notwithstanding the existence of a third party liable to pay. Sufficient financing of services is determined by the resources assigned to the autonomous communities in conformity to what is established in the laws of autonomic financing.

Inclusion of a new service in the catalog of services of the National Health System is accompanied by an economic memo that contains the positive or negative financial impact it is expected to imply. This memo is brought up to the Council of Fiscal Policy and Finance for analysis and approval as to whether to proceed.

Fairness in financing

[edit]Prior to 1986, public financing of health care occurred mostly through highly regressive payroll taxes. In 1986, the law that established the Spanish National Health System also shifted financing toward progressive general taxes and away from payroll taxes.[19] In a 2000 report, the World Health Organization ranked Spain 26th of 191 countries in its fairness in financing.[20]

In 1999, reform to income tax deductions allowed high income earners to deduct more for private insurance. Although this reform was intended to decrease overconsumption of health care services, it had the side effect of more regressive financing of public health services. Nevertheless, that same year payroll taxes were completely phased out while higher indirect taxes (on excise goods such as alcohol and tobacco) were earmarked for health care.[21]

Functional organization

[edit]Individual health card

[edit]

Article 57 of the Law of Cohesion establishes that citizens' access to health services will be facilitated by use of an individual health card (tarjeta sanitaria individual), as the administrative document that accredits its holder and provides certain basic data.

In order to best facilitate collaboration, quality, and continuity of services, the each card includes a standardized form of basic identification data for the holder, and indicates in which autonomic health service the person is enrolled. In particular, the cards incorporate a digital form of this information; health facilities throughout Spain have appropriate equipment to read the digital information from the cards. A cardholder should thereby be able to access all the services of all relevant health professionals throughout the country.

Clinical history

[edit]A patient's clinical history is a medical-legal document that arises from the interactions between health professionals and their clients. From a medical and legal point of view, the clinical history is the only document valid to track this history of interactions. In primary care, where methods of health promotion are important, the clinical history document is sometimes known as a "health history" (historia de salud) or "life history" (historia de vida).

Clinical histories in the SNS

[edit]The Clinical History of the [Spanish] National Health System (Historia Clínica Digital del Sistema Nacional de Salud, HCDSNS) is intended to guarantee citizens and health professionals access to whatever clinical information is relevant for medical care of a particular patient. This history should be available at all authorized locations, but nowhere else: except as needed for treatment, the information is considered confidential and access is restricted.[22]

Health Areas

[edit]The term "Health Area" (Área de Salud) refers to an administrative district that brings together a functional and organizational group of health centers and primary care professionals. A Health Area may be exclusively focused on primary care or may include specialists as well. Some autonomous communities use different term, such as Direction of a sector (Dirección de sector), or of a comarca, district, department, or other territorial unit used in that autonomous community.[23]

Basic Health Zones

[edit]

Although the autonomous communities differ among themselves in layering subdivisions of their health areas, all eventually come down to a Health Zone (Zona de Salud) or Basic Health Zone (Zona Básica de Salud) as the unit for a primary health care team. In Andalusia, for example, each existing Basic Health Zone takes care of a population between 5,000 and 20,000 inhabitants. The Basic Health Zone is served by a single general hospital and specialists' center.[24]

Primary Care

[edit]Article 12 of the Law of Cohesion establishes the concept of "primary care," the basic level of patient care that guarantees the comprehensiveness and continuity of care throughout the patient's life, acting as manager and coordinator of cases and regulator of issues. Primary care includes health promotion, health education, prevention of illness, health care, maintenance and recuperation of health, as well as physical rehabilitation and social work. Primary health care includes service provided either on-demand, scheduled, or urgently, both in the clinic as well as in the patient's home.

Specialized care

[edit]Article 13 of the Law of Cohesion regulates characteristics of health care offered in Spain by medical specialists, which is provided at the request of primary care physicians. This may be in-patient hospital care or out-patient consultation at specialist centers or day hospitals. It includes care, diagnosis, therapy, rehabilitation and certain preventive care, as well as health promotion, health education and prevention of illness whose nature makes it appropriate to handle at this level. Specialized care guarantees the continuity of integrated patient care once the capabilities of primary care have been exhausted and until matters can be returned to that level. Insofar as patient condition allows, specialized care is offered in out-patient consultation and in day hospitals. As of 2010, Spain recognizes fifty distinct medical specialties.[25]

Social-health care

[edit]Article 14 of the Law of Cohesion defines social-health care (atención sociosanitaria) as the combination of care for those patients, generally those with a chronic illness, whose would benefit from the simultaneous and synergistic provision of health services and social services to increase their personal autonomy, palliate their limitation or hardships, and facilitate their social reinsertion. This group includes:

- a) Longterm health care.

- b) Health care connected to convalescence.

- c) Rehabilitation after illness

Registered health professionals

[edit]2000 data from the INE (Spain's National Institute of Statistics) counts 616,232 individuals credentialed by a professional association as health care professionals. The largest number of these are nursing professionals; that is also the profession with the highest percentage of women. The following table is a breakdown of some of the INE statistics. No exact breakdown is available to indicate what number of these might be related to mental health and psychotherapy or clinical psychology.

| Type of association | Males | Females | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians | 119,018 | 94,959 | 213,977 |

| Dentists | 14,575 | 11,122 | 25,697 |

| Podiatrists | 2,292 | 2,735 | 5,027 |

| Physiotherapists | 10,102 | 21,127 | 31,229 |

| Nursing professionals | 41,719 | 208,420 | 250,139 |

| Veterinarians | 16,806 | 11,382 | 28,188 |

| Pharmacists | 18,409 | 43,566 | 61,975 |

| Total | 222,922 | 413,321 | 616,232 |

Health establishments

[edit]Healthcare centers

[edit]Royal Decree 1277/2003, of 10 October, establishes the general bases for authorization of health centers, services and establishments. It defines "healthcare center" (centro sanitario) as the organized combination of technical means and installations in which trained professionals, identified by their official certification or professional qualification, undertake basic health care activities with the purpose of improving people's health. These may be integrated into one or more health services, which constitute its healthcare portfolio.[27]

Consultorios

[edit]Certain healthcare centers (centros sanitarios) are referred to as consultorios, a term roughly equivalent to British English "surgery" or American English "doctor's office." These are offices that, while not full-fledged health centers (centros de salud), nonetheless provide care beyond primary care. Some terms used are consultorios rurales, consultorios locales, and consultorios periféricos (respectively, rural, local and "peripheral"; that last means a center located in a community other than the main settlement of a municipality), but other terms may exist, analogous to those that refer to various types of health centers.[28]

According to the 2008 National Catalog of Hospitals (Catálogo Nacional de Hospitales 2008), Spain in 2007 had a total of 10,178 consultorios that allowed health professionals to provide more local services than the health centers in their respective zones, with the purpose of bringing basic services closer to people who reside in nuclei dispersed through rural areas that tend to have an older than average population.[29]

Health centers

[edit]

A health center (centro de salud, distinct from the smaller "healthcare center" centro sanitario) in Spain's SNS is main physical and functional structure devoted to coordinated global, integral, permanent and continuing primary care, based in a team of health care professionals and other professionals who work there as a team.[30]

Health centers basically practice the general medicine or family medicine, providing a unity of care in which a specialist in community and family medicine is responsible to provide preventive care, health promotion, diagnosis and basic treatment on an outpatient basis. According to the 2008 National Catalog of Hospitals (Catálogo Nacional de Hospitales), in 2007 Spain had 2,913 health centers.[31]

Specialized centers

[edit]Specialized centers are healthcare centers where different health care professionals provide services to particular group identified by common pathologies, age, or other common characteristics. Among these are:

- Dental clinics

- Focused on care of the teeth and mouth.

- Centers for assisted human reproduction

- Biomedical teams focused on assisted reproductive technology.

- Centers for voluntary interruption of pregnancy

- Provide abortion services in legally permitted cases.

- Centers for major outpatient surgery

- Provide surgery and subsidiary services including general, local and regional anesthesia and sedation. For surgeries that require only brief post-operative care and therefore do not require overnight hospitalization.

- Dialysis centers

- For patients with failed kidneys.

- Diagnostic centers

- Dedicated to diagnostic, analytic and imaging services.

- Mobile health care centers

- Carry human and technical means for the purpose of health care activities.

- Transfusion centers

- Carry out all activities related to the extraction and verification of human blood and its components, and of treatment, storage, and distribution.

- Tissue banks

- Conserve and guarantee the quality of tissues after they are obtained and until they are used as allografts or autografts.

- Medical inspection centers

- (Centros de reconocimiento médico), where examinations and other tests of ability are carried out for applicants or holders of medical and other health care permits or licenses.

- Mental health centers

- Diagnose and treat mental illness on an outpatient basis.

Specialized health care establishments

[edit]Specialized health care establishments are private centers that provide a suite of health care products, ranging from medicines to sophisticated prostheses. These establishments are grouped by specialty and, on that account, must have accredited or certified technical personnel. Among these establishments are:

- Pharmacies

- Private establishments operated in the public interest, subject to health care planning established by the autonomous communities, which provide the public with basic services recognized in Article 1 of Law 16/1997, of 25 April, that regulates pharmacy services (Ley 16/1997, de 25 de abril, de regulación de los servicios de las oficinas de farmacia).

- Botiquines

- (singular: Botiquín) are authorized to hold, conserve and dispense medicines and health care products in places where there would be special difficulties of accessibility of a pharmacy.

- Optometric offices (Ópticas)

- Evaluate visual capacity using optometric techniques; crafting, sale, verification and control of adequate means for the prevention, detection, protection, and improvement of visual acuity.

- Orthopedia centers

- Dispense orthopedic health care products such as prostheses and orthotics, technical devices to alleviate loss of autonomy, functionality, or physical capacity.

- Audioprosthesis centers

- Dispense health care products, intended for the correction of auditory deficiencies, such as hearing aids, with adaptation individualized to each patient.

Hospitals

[edit]

A hospital is a health care establishment that provides inpatient care and specialized (and other) care, providing such services as are needed in its geographical area. A hospital can be a single structure or a hospital complex, even including branch buildings off of its main campus; it can also integrate any number of specialized centers.[32]

A similar concept to a hospital is a clinic. In Spain, a clinic (clínica) is a health center, typically a private one, where patients can receive health coverage in a broad range of specialties. Some of these clinics include very up-to-date operating theaters capable of providing minimally invasive surgery, and "hospitalization zones" where patients can recuperate on an inpatient basis. In large Spanish cities, there are numerous clinics. These are the facilities that are normally used by health care professionals whose medical societies cover it: ASISA, Adeslas, etc.[33]

The General Health Law of 1986 establishes that the level of specialized care provided in hospitals and their dependent specialty centers will focus care on complex health problems. Hospital centers will develop, besides their functions strictly related to health care, functions of health promotion, prevention of illnesses and investigation and teaching, in accord with the programs of each area of health, with the object of complementing their activities with those developed by the primary care network.[34]

As elsewhere in the world, the size of hospitals in Spain is often gauged by the number of "installed beds" (camas instaladas). This is the number of hospital beds with fixed locations; at any given time, some beds may be out of commission.

General and specialized hospitals

[edit]General hospitals treat a broad range of pathologies and typically provide services including surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, and pediatrics. Other hospitals are more specialized. The following list includes most of the common types of specialized hospitals in Spain, but is not intended to be exhaustive.

|

|

Health care contracts

[edit]Spanish government-run healthcare administrations sign health care contracts (conciertos sanitarios) with privately run entities that provide health care services. They are regulated by the provisions of the General Health Law and the current rules of government contracting. There are some special cases where the relation between the hospital and the managing entity is regulated by a special arrangement called a Convenio de Vinculación or Convenio Singular ("Linkage Convention" or "Singluar Convention").[35] In Catalonia there are also centers integrated into the Network of Hospitals for Public Use (Red de Hospitales de Utilización Pública, XHUP) as outlined in the supplement to Decree 124/2008 of the Department of Health of the Autonomous Government of Catalonia (Anexo del Decreto 124/2008 del Departamento de Salud de la Generalitat de Catalunya).

Patrimonial dependency

[edit]The patrimonial dependency (dependencia patrimonial) of a hospital (or other health care facility) is the individual or other juridical entity that owns, at least, the building occupied by the facility. Hospitals that are under the dependency of Spanish Social Security belong primarily to the General Treasury of Social Security, although there is a special group within Social Security for the Mutuals of Accidents and Occupational Diseases (Mutuas de Accidentes de Trabajo y Enfermedades Profesionales, MATEP). There are also a few cases where patrimony is shared by two or more public entities on a consortium basis.

The 2009 National Catalog of Hospitals contains information about the patrimonial dependency of hospitals, summarized as follows; hospital complexes are each counted here as a single hospital:[36]

| Patrimonial Dependency | Number of centers | Number of beds |

|---|---|---|

| Civil, public (SNS) | 301 | 103,655 |

| Ministry of Defence | 8 | 1,458 |

| MATEP | 22 | 1,741 |

| Private, charitable | 120 | 19,980 |

| Private, non-charitable | 349 | 33,458 |

| TOTAL | 804 | 160,292 |

40 percent of stays in private hospitals are arranged and paid for by the public system.[36]

The 2008 National Catalog of Hospitals gives the following breakdown of types of hospitals.[37]

| Type of care | Number of hospitals | Number of beds | Beds per 100,000 population | Percent in the public system |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute illness | 591 | 131,510 | 290.5 | 72.1% |

| Psychiatric | 90 | 16,028 | 35.5 | 37.5% |

| Geriatric | 119 | 12,945 | 28.7 | 34.2% |

High technology resources

[edit]Health care centers, principally hospitals and specialty centers, have high technology capabilities used primarily to perform better patient diagnoses. The following breakdown of such facilities is based on the 2008 National Catalog of Hospitals.

| Type of equipment | Total | Rate per million inhabitants |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray computed tomography (CTC) | 654 | 14.4 |

| Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | 417 | 9.2 |

| Gamma camera (GAM) | 232 | 5.1 |

| Hemodynamics (HEM) facility | 220 | 4.9 |

| Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) | 46 | 1.0 |

| Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) | 194 | 4.3 |

| Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) | 91 | 2.0 |

| Radiation therapy with cobalt | 40 | 0.9 |

| Medical linear particle accelerator (linac) | 160 | 3.5 |

| Positron emission tomography (PET) | 32 | 0.7 |

| Mammography | 481 | 10.6 |

| Bone Densitometry | 165 | 3.6 |

| Hemodialysis equipment | 3,225 | 71.2 |

Services

[edit]Article 7 of the Law of Cohesion establishes the catalog of services of the National Health System, with the object of guaranteeing the basic and common conditions for an adequate level of integrated, continuous health care. Health care services include prevention, diagnosis, therapy and rehabilitation, as well as promotion and maintenance of citizens' health.

Article 11 of the law establishes the basic lines of public health services:

- 1. The public health service is the ensemble of initiatives organized by public administrations to preserve, protect and promote the health of the population. It is a combination of sciences, capabilities and attitudes directed to the maintenance and improvement of the health of all persons through collective and social acts.

- 2. The services in this ambit include the following activities: Epidemiological information and vigilance. Protection of health. Promotion of health. Vigilance and control of possible health risks derived from the importation, exportation and transit of merchandise and of international travel. Promotion and protection of environmental safety. Promotion and protection of health on the job.

- 3. Public health services are to be exercised with an integral character, from public health structures to administrations and the infrastructure of primary care of the National Health System.[39]

Primary care services

[edit]Primary care services constitute the majority of the services of the SNS; this is true of health promotion and education, prevention of illness, hands-on health care, health maintenance, recuperation, rehabilitation, and social work.

The following catalog demonstrates preventive activities, health promotion and education, family care and community care as performed in primary care centers.[40]

- Inculcate healthy life habits in adolescents with respect to the use of tobacco, alcohol and recreational drugs as well as harmful eating disorders and healthy conduct with respect to sexuality.

- Orientation of women during pregnancy and birth, early diagnosis of gynecological cancers and breast cancer, detection and care of problems related to menopause. Family planning.

- Pediatrics, including infant and child health care, nutrition, general counsel on child development, health education and childhood accidents. Vaccinations.

- Care for adults in risk groups or with chronic conditions. Counsel on healthy life styles and detection of health problems.

- Geriatrics: promotion of health and prevention of illness. Homecare for the housebound.

- Detection of violence against women and domestic abuse, as well as child abuse, elder abuse, and abuse of disabled people.

- Dentistry: Care, diagnosis and therapy, health promotion and education, and illness prevention related to the teeth and mouth.

- Care of terminal patient: integral, individual and continual care either in the home or at a health center.

- Mental health care: prevention and promotion to maintain mental health, in coordination with specialists.

Specialized care

[edit]

At times, patients will require specialized health care services. These may be provided in external consultations, day hospitals, or on an inpatient basis.

Examples of specialized services are intensive and critical care, anesthesia, defibrillation, but also some forms of hemotherapy, rehabilitation, and even nutrition, diet, post-partum treatment, and family planning, especially assisted reproductive technology. Specialized treatment can also be involved in detection, prescription and implementation of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, especially those related to prenatal diagnosis in risk groups, diagnosis by imaging, interventionist radiology, hemodynamics, nuclear medicine, neurophysiology, endoscopy, lab tests, biopsies, radiotherapy, radiosurgery, renal lithotripsy, dialysis, techniques of respiratory therapy, organ transplants and other tissue and cell transplants.[41]

Urgent care

[edit]

Emergency medicine is health care provided in cases where emergency care is needed. Emergency medicine is practiced both in healthcare facilities and at the site of work accidents, traffic accidents, etc. or in the home of a patient whose condition prevents them from getting to a healthcare facility. Emergency medicine is a 24-hour-a-day service provided, in particular, by physicians and other medical professionals in hospital emergency rooms, but also in ambulances, medical evacuation helicopters, etc. en route to such facilities.[42]

Pharmaceutical services

[edit]Medications in Spain are regulated under Law 29/2006 of 26 July, of guarantees and rational use of medications and health care products (Ley 29/2006, de 26 de julio, de garantías y uso racional de los medicamentos y productos sanitarios).[43] One of the SNS's priorities with respect to pharmaceuticals is to teach patients to make rational use of medications and to avoid, insofar as possible, unsupervised self-medication.

Pharmaceutical services include medications and health products are provided to patients according to their clinical needs, in precise doses and over an adequate period at the least cost possible. Medications are dispensed by pharmacies, each of which is headed by a licensed pharmacist.

All medications to be prescribed to patients must either be authorized and registered by the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios), or must be formulations prepared by licensed pharmacists. Exceptions to this requirement are cosmetics, dietetic products, dental products and other sanitary products, as well as drugs classified as advertising, homeopathic medicines, and articles and accessories advertised to the general public and where the purchaser pays the full price (that is, no money comes from SNS-related sources).

Spanish patients make a copayment when they acquire pharmaceuticals. The distribution of the cost is as follows:[44]

- Medications dispensed as part of hospitalization are free to the patient.

- Other prescriptions are financed as follows

- Most pensioners and their beneficiaries receive their medicines for free. Pensioners who were public functionaries and are protected by MUFACE (Mutualidad General de Funcionarios Civiles del Estado) pay 30 percent of prescription cost.

- Non-pensioners pay 40 percent of the price of prescription drugs. Active functionaries protected by MUFACE pay 30 percent.

- Communities affected by toxic oil syndrome and patients with AIDS receive their prescriptions for free.

- Individuals with toxic treatments pay 10 percent, up to a maximum of 2.64 euros per prescription.

Orthoprosthetic and complementary services

[edit]Orthoprosthetic services can be permanent surgically implanted prostheses, external prostheses, special orthoses and prostheses including hearing aids and earmolds for children up to age 16 with bilateral hearing impairments.[45][46]

"Complementary services" include complex dietary therapies, vehicles for invalids, and home oxygen therapy.[45][46]

Health care transport

[edit]

The health care transport infrastructure transports people who are ill, accident victims, or otherwise in need of medical attention. It includes ambulances, as well as air ambulances: helicopters and airplanes whose interiors are specially modified for the purpose. For most purposes, of course, ground transport is preferred, but sometimes distances or the difficulty of reaching particular locations make air transport more practical.

Demographics of Spain

[edit]| Population pyramid 2008[47] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

According to data from the National Institute of Statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, INE), as of January 1, 2018,[48] Spain has a population of 46,659,302, of whom 22,882,286 (49,04%) are male and 23,777,015 (50.96%) female. In recent years, this population has been increasing slowly but progressively. In the last decade, the increase has been largely through immigration: 4,572,055 Spanish residents are foreigners.

These numbers count only citizens and legal immigrants. The health care system must also provide services for thousands of illegal immigrants and for the many tourists who visit Spain each year.

Population pyramid

[edit]Analysis of the population pyramid shows that

- 20 percent of the total population is under 20 years of age.

- 24 percent of the total population is 20 to 40 years of age.

- 31 percent of the total population is 40 to 60 years of age.

- 25 percent of the total population is at least 60 years old.

This structure is typical of a modern demographic regimen, with an evolution toward an aging population and a declining birth rate. This means that Spain has to expect an increase in use of the services that are targeted at older adults. This effect is further exacerbated by a steadily increasing life expectancy.

|

| Graphic from the Spanish-language Wikipedia, based on data from the INE |

See also

[edit]- National Transplant Organization achieved the highest rate of donors in the world in 2006.

- Miguel de Cervantes Health Care Centre

- Social Security in Spain

Notes

[edit]- ^

- a. La extensión de sus servicios a toda la población.

- b. La organización adecuada para prestar una atención integral a la salud, comprensiva tanto de la promoción de la salud y prevención de la enfermedad como de la curación y rehabilitación.

- c. La coordinación y, en su caso, la integración de todos los recursos sanitarios públicos en un dispositivo único.

- d. La financiación de las obligaciones derivadas de esta Ley se realizará mediante recursos de las Administraciones públicas, cotizaciones y tasas por la prestación de determinados servicios.

- e. La prestación de una atención integral de la salud procurando altos niveles de calidad debidamente evaluados y controlados.

- ^ Decreto 2065/1974, de 30 de mayo

- ^ Ley 14/1986, de 25 de abril, General de Sanidad, BOE number 102 of 1986-04-29, pages 15207–15224. (Text of the law, in Spanish.)

- ^ El Sistema Nacional de Salud se concibe así como el conjunto de los servicios de salud de las Comunidades Autónomas convenientemente coordinados. - Preamble to the General Health Law of 1986.

- ^ Francisco José Villar Rojas (2020). "La Ley 15/97,".

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "LEY 16/2003, de 28 de mayo, de cohesión y calidad del Sistema Nacional de Salud". Jefatura del Estado (BOE número 128 de 29/5/2003). Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ^ Available online at http://boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2012-5403

- ^ http://boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2012-5403. Article 2, section Trece. Checked on March 18, 2013.

- ^ "Organización del Ministerio de Sanidad y Política Social (España)". msps.es. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ^ Colectivo El Bosque (2008-10-15). "Qué es, como funciona el Consejo Interterritorial del Sistema Nacional de Salud (CISNS)". e-ras. Revista on.line de información sanitaria. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- ^ El Consejo Interterritorial está constituido por el Ministro de Sanidad y Consumo, que ostentará su presidencia, y por los Consejeros competentes en materia de sanidad de las comunidades autónomas. La vicepresidencia de este órgano la desempeñará uno de los Consejeros competentes en materia de sanidad de las comunidades autónomas, elegido por todos los Consejeros que lo integran. (from Article 70 of the Ley de cohesión y calidad de SNS.)

- ^

El CISNS conocerá, debatirá entre otros aspectos, y, en su caso, emitirá recomendaciones sobre las siguientes materias:

- a) El desarrollo de la cartera de servicios correspondiente al Catálogo de Prestaciones del Sistema Nacional de Salud, así como su actualización.

- b) El establecimiento de prestaciones sanitarias complementarias a las prestaciones básicas del Sistema Nacional de Salud por parte de las comunidades autónomas.

- c) Las garantías mínimas de seguridad y calidad para la autorización de la apertura y puesta en funcionamiento de los centros, servicios y establecimientos sanitarios.

- d) Los criterios generales y comunes para el desarrollo de la colaboración de las oficinas de farmacia.

- e) Los criterios básicos y condiciones de las convocatorias de profesionales que aseguren su movilidad en todo el territorio del Estado.

- f) La declaración de la necesidad de realizar las actuaciones coordinadas en materia de salud pública a las que se refiere esta ley.

- g) Los criterios generales sobre financiación pública de medicamentos y productos sanitarios y sus variables.

- h) El establecimiento de criterios y mecanismos en orden a garantizar en todo momento la suficiencia financiera del sistema.

- ^

- Las comunidades autónomas ejercerán las competencias asumidas en sus estatutos y las que el estado les transfiera o, en su caso, les delegue.

- Las decisiones y actuaciones publicas previstas en esta ley que no se hayan reservado expresamente al estado se entenderán atribuidas a las comunidades autónomas.

- ^

- a) Control sanitario del medio ambiente: Contaminación atmosférica, abastecimiento de aguas, saneamiento de aguas residuales, residuos urbanos e industriales.

- b) Control sanitario de industrias, actividades y servicios, transportes, ruidos y vibraciones.

- c) Control sanitario de edificios y lugares de vivienda y convivencia humana, especialmente de los centros de alimentación, peluquerías, saunas y centros de higiene personal, hoteles y centros residenciales, escuelas, campamentos turísticos y áreas de actividad físico deportivas y de recreo.

- d) Control sanitario de la distribución y suministro de alimentos perecederos, bebidas y demás productos, directa o indirectamente relacionados con el uso o consumo humanos, así como los medios de su transporte.

- e) Control sanitario de los cementerios y policía sanitaria mortuoria.

- ^ "Transferencias del Insalud" (PDF). Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Política Social (Ministry of Health and Social Policy). Retrieved 2010-01-06.

- ^ "Cifras de población referidas al 01/01/2009. Resumen por Comunidades Autónomas". Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spain). Retrieved 2010-01-06.

- ^

- Artículo 39: Los poderes públicos aseguran la protección social, económica y jurídica de la familia.

- Artículo 43: Se reconoce el derecho a la protección de la salud. Compete a los poderes públicos organizar y tutelar la salud pública a través de medidas preventivas y de las prestaciones y servicios necesarios. La Ley establecerá los derechos y deberes de todos a ete respecto. Los poderes públicos fomentarán la educación sanitaria, la educación física y el deporte.

- Artículo 49. Los poderes públicos realizarán una política de previsión, tratamiento, rehabilitación e integración de los disminuidos físicos, sensoriales y psíquicos.

- ^

- Artículo 3. Los extranjeros gozarán en España, en igualdad de condiciones que los españoles, de los derechos y libertades reconocidos en el Título I de la Constitución y en sus leyes de desarrollo, en los términos establecidos en esta Ley Orgánica.

- Artículo 10. Los extranjeros tendrán derecho a ejercer una actividad remunerada por cuenta propia o ajena, así como al acceso al Sistema de la Seguridad Social, en los términos previstos en esta Ley Orgánica y en las disposiciones que la desarrollen.

- Artículo 12. Los extranjeros que se encuentren en España inscritos en el padrón del municipio en el que residan habitualmente, tienen derecho a la asistencia sanitaria en las mismas condiciones que los españoles. Los extranjeros que se encuentren en España tienen derecho a la asistencia sanitaria pública de urgencia ante la contracción de enfermedades graves o accidentes, cualquiera que sea su causa, y a la continuidad de dicha atención hasta la situación de alta médica. Los extranjeros menores de dieciocho años que se encuentren en España tienen derecho a la asistencia sanitaria en las mismas condiciones que los españoles. Las extranjeras embarazadas que se encuentren en España tendrán derecho a la asistencia sanitaria durante el embarazo, parto y postparto.

- ^ Costa-Font, Joan; Gil, Joan (December 2009). "Exploring the pathways of inequality in health, health care access and financing in decentralized Spain". Journal of European Social Policy. 19 (5): 446–458. doi:10.1177/0958928709344289. S2CID 154007289.

- ^ World Health Organisation, World Health Staff, (2000), Haden, Angela; Campanini, Barbara, eds., The world health report 2000 - Health systems: improving performance (PDF), Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation, ISBN 92-4-156198-X

- ^ Puig-junoy, Jaume; Rovira, Joan (June 2004). "Issues raised by the impact of tax reforms and regional devolution on health-care financing in Spain, 1996 - 2002". Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy. 22 (3): 453–464. doi:10.1068/c0236. S2CID 55110733.

- ^ msc.es (ed.). "Historia Clínica Digital del Sistema Nacional de Salud (España)". Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ^ "Catálogo de Centros de Atención Primaria del Sistema Nacional de Salud 2009". msc.es. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ^ "Organización del Sistema Nacional de Salud (España)" (PDF). msps.es. Retrieved 2009-12-28.

- ^ "Especialidades médicas en España". ortopedia.rediris.es. Archived from the original on 2010-01-06. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- ^ "Profesionales sanitarios colegiados por tipo de profesional, años y sexo". INE. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- ^ "Real Decreto 1277/2003, de 10 de octubre, por el que se establecen las bases generales sobre autorización de centros, servicios y establecimientos sanitarios". BOE nº254 23 de octubre de 2003. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

- ^ "Centros de Sanitarios del SNS". msc.es. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ^ "Recursos y actividades del SNS" (PDF). msps.es. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ^ "Real Decreto 1277/2003, de 10 de octubre. ANEXO II Definiciones de centros, unidades asistenciales y establecimientos sanitarios. Centro de salud". BOE nº254 23 de octubre de 2003. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

- ^ "Actividades y recursos del SNS" (PDF). msps.es. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ^ "Definición de hospital". definicionabc.com. Retrieved 2010-01-07.

- ^ "Un nuevo concepto de clínica". clinicastarte.com. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- ^ "Funciones de los hospitales". noticias.juridicas.com. Retrieved 2010-01-07.

- ^ "Ley 2/2002, de 17 de abril, de Salud. Colaboración con la iniciativa privada". noticias.juridicas.com. Retrieved 2010-01-07.

- ^ a b "Recursos y actividades del SNS. Hospitales" (PDF). msps.es Ministerio de Sanidad. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ^ "Recursos y actividades del SNS. Hospitales" (PDF). msps.es Ministerio de Sanidad. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ^ "Recursos sanitarios de alta tecnología" (PDF). msps.es. Retrieved 2010-01-17.

- ^

- 1. La prestación de salud pública es el conjunto de iniciativas organizadas por las Administraciones públicas para preservar, proteger y promover la salud de la población. Es una combinación de ciencias, habilidades y actitudes dirigidas al mantenimiento y mejora de la salud de todas las personas a través de acciones colectivas o sociales.

- 2. Las prestaciones en este ámbito comprenderán las siguientes actuaciones: Información y vigilancia epidemiológica. Protección de la salud. Promoción de la salud. Vigilancia y control de los posibles riesgos para la salud derivados de la importación, exportación o tránsito de mercancías y del tráfico internacional de viajeros. Promoción y protección de la sanidad ambiental. Promoción y protección de la salud laboral.

- 3. Las prestaciones de salud pública se ejercerán con un carácter de integralidad, a partir de las estructuras de salud pública de las Administraciones y de la infraestructura de atención primaria del Sistema Nacional de Salud.

- ^ "Prestaciones sanitarias del Sistema Nacional de Sald. Atención primaria" (PDF). msps.es. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ^ "Prestaciones de la Atención Esppecializada" (PDF). msps.es.

- ^ "Urgencia médica". tuotromedico.com.

- ^ "Ley 29/2006, de 26 de julio, de garantías y uso racional de los medicamentos y productos sanitarios" (PDF). boe.es. BOE. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ "Prestaciones famaceúticas del Sistema Nacional de Salud". seg-social.es. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ a b "Prestaciones complementarias". seg-social.es. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ a b "Prestaciones complementarias". Servei Català de la Salut. Retrieved 2010-08-13.

- ^ "Revisión del Padrón municipal 2008. Datos por municipios. Población por sexo, municipios y edad (grupos quinquenales). España". Instituto Nacional de Estadística, España. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- ^ National Institute of Statistics of Spain (25 June 2018). "Population data as of January 1st, 2018 and Migration statistics" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadística.

- ^ ". Serie histórica de población. España". Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) España. Archived from the original on 2016-10-10. Retrieved 2010-01-15.