Ste. Genevieve, Missouri | |

|---|---|

City | |

Maison Bequette-Ribault, c. 1805; privately owned | |

| Nickname: "The Mother City of the West"[1] | |

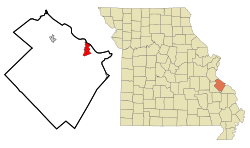

Location of Ste. Genevieve, Missouri | |

U.S. Census Map | |

| Coordinates: 37°58′32″N 90°02′52″W / 37.97556°N 90.04778°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Missouri |

| County | Ste. Genevieve |

| Township | Ste. Genevieve |

| Incorporated | 1805 |

| Named for | Saint Genevieve |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Brian Keim |

| Area | |

• Total | 3.90 sq mi (10.11 km2) |

| • Land | 3.90 sq mi (10.10 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 427 ft (130 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 4,999 |

| • Density | 1,282.12/sq mi (495.00/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| Zip code | 63670 |

| Area code | 573 |

| FIPS code | 29-64180[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2396523[3] |

| Website | http://www.stegenevieve.org/ |

Ste. Genevieve (French: Sainte-Geneviève [sɛ̃t ʒənvjɛv]) is a city in Ste. Genevieve Township and is the county seat of Ste. Genevieve County, Missouri, United States.[5] The population was 4,999 at the 2020 census.[6] Founded in 1735 by French Canadian colonists and settlers from east of the river, it was the first organized European settlement west of the Mississippi River in present-day Missouri. Today, it is home to Ste. Genevieve National Historical Park, the 422nd unit of the National Park Service.

History

[edit]Founded around 1740 by Canadian settlers and migrants from settlements in the Illinois Country just east of the Mississippi River, Ste. Geneviève is the oldest permanent European settlement in Missouri. It was named for Saint Genevieve (who lived in the 5th century AD), the patron saint of Paris, the capital of France. While most residents were of French-Canadian descent, many of the founding families had been in the Illinois Country for two or three generations. It is one of the oldest colonial settlements west of the Mississippi River.[7]

This area was known as New France, Illinois Country, or the Upper Louisiana territory. Traditional accounts suggested a founding of 1735 or so, but historian Carl Ekberg has documented a more likely founding about 1750. The population to the east of the river needed more land, as the soils in the older villages had become exhausted. Improved relations with hostile Native Americans, such as the Osage, made settlement possible.[8]

Prior to arrival of French Canadian settlers, indigenous peoples of succeeding cultures had lived in the region for more than one thousand years. The best known prior to the historic tribes were the Mississippian culture, which developed complex earthworks at such sites as Cahokia, and had a broad cross-continental trading network along the Mississippi-Ohio river waterways, from the south to near the Great Lakes.

At the time of European settlement, however, no Indian tribe lived nearby on the west bank. Jacques-Nicolas Bellin's map of 1755, the first to show Ste. Genevieve in the Illinois Country, showed Kaskaskia natives on the east side of the river, but no Indian village on the west side within 100 miles of Ste. Genevieve.[9] Osage hunting and war parties did enter the area from the north and west. The region had been relatively abandoned by 1500, likely due to environmental exhaustion, after the peak of Mississippian culture civilization at Cahokia, the largest city of this culture.

At the time of its founding by ethnic French, Ste. Genevieve was the last of a triad of French Canadian settlements in this area of the mid-Mississippi Valley. About five miles northeast of Ste. Genevieve on the east side of the river was Fort de Chartres (in the Illinois Country); it stood as the official capital of the area. Kaskaskia, which became Illinois's first capital upon statehood, was located about five miles southeast. Prairie du Rocher and Cahokia, Illinois (an independent settlement not attached to the ancient Mississippian site) were other early local French colonial settlements on the east side of the river.

Following defeat by the British in the French and Indian War, in 1762 under the Treaty of Fontainebleau, France secretly ceded the area of the west bank of the Mississippi River to Spain, which formed Louisiana (New Spain). The Spanish moved the capital of Upper Louisiana from Fort de Chartres fifty miles upriver to St. Louis. They ruled with a light hand and often through mostly French-speaking officials. Although under Spanish control for more than 40 years, Ste. Genevieve retained its French language, customs and character. Like other European colonists, the French held enslaved African Americans as workers. Most slaveholders had a few such workers, as they had relatively small farms. Some slaves were used as workers in lead mining.

In 1763, the French ceded the land east of the Mississippi to Great Britain in the Treaty of Paris that ended Europe's Seven Years' War, also known on the North American front as the French and Indian War. French-speaking people from Canada and settlers east of the Mississippi went west to live beyond British rule; they also flocked to Ste. Genevieve after George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763. This transformed all of the captured French land between the Mississippi and the Appalachian Mountains, except Quebec, into an Indian reserve. The king required settlers to leave or get British permission to stay. These requirements were regularly violated by European-American settlers, who resented efforts to restrict their expansion west of the Appalachians.

During the 1770s, bands of Little Osage and Missouri tribes repeatedly raided Ste. Genevieve to steal settlers' horses. But the fur trade, marriage of French-Canadian men with Native American women, and other commercial dealings created many ties between Native Americans and the Canadiens. During the 1780s, some Shawnee and Lenape (Delaware) migrated to the west side of the Mississippi following rebel American victory in its Revolutionary War. The tribes established villages south of Ste. Genevieve. The Peoria also moved near Ste. Genevieve in the 1780s but had a peaceful relationship with the village. It was not until the 1790s that the Big Osage pressed the settlement harder; they conducted repeated raids, and killed some settlers. In addition, they attacked the Peoria and Shawnee.[10]

While at one point Spanish administrators wanted to attack the Big Osage, there were not sufficient French settlers to recruit for a militia to do so. The Big Osage had 1250 men in their village, and lived in the prairie. In 1794 Francisco Luis Héctor de Carondelet, the Spanish governor at New Orleans, appointed brothers Pierre Chouteau and Auguste Chouteau of St. Louis to have exclusive trading privileges with the Big Osage. They built a fort and trading post on the Osage River in Big Osage territory. While the natives did not entirely cease their raids on Ste. Genevieve, commercial diplomacy and rewards of the fur trade eased some relations.[10]

Le Vieux Village (Old Ste. Genevieve c. 1750)

[edit]Following the great flood of 1785, the town moved from its initial location on the floodplain of the Mississippi River, to its present location two miles north and about a half mile inland. It continued to prosper as a village devoted to agriculture, especially wheat, maize and tobacco production. Most of the families were yeomen farmers, although there was a wealthier level among the residents. The village raised sufficient grain to send many tons of flour annually for sale to Lower Louisiana and New Orleans. This was essential to the survival of the southern colonies, which could not grow sufficient grain in their climate. In 1807, Frederick Bates, the secretary of the Louisiana Territory after the United States made the Louisiana Purchase, noted Ste. Genevieve was "the most wealthy village in Louisiana" (meaning the full Territory).[11]

1852 Ste. Genevieve Stampede

[edit]On 4th September 1852, eight enslaved men, including five from Ste. Genevieve, tried to escape enslavement by crossing the Mississippi River towards Sparta, Illinois, "widely reputed as a haven for freedom seekers". They had been working in mines owned by the Valle family of Ste. Genevieve, some because they were held ("owned") by the Valles. On 9th September, slaveholders put out a $1600 reward for the return of the men who were all recaptured.[12]

Architecture

[edit]The oldest surviving buildings of Ste. Genevieve, described as "French Creole colonial", were all built during the period of Spanish rule in the late 18th century. The most distinctive buildings of this period were the "vertical wooden post" constructions. Walls of buildings were built based on wood "posts" either dug into the ground (poteaux en terre) or set on a raised stone or brick foundation (poteaux sur solle). This was different from the log cabin style associated with the Anglo-American frontier settlements of the United States northeast, mid-Atlantic and Upper South, for which logs are stacked horizontally.

The most distinctive of the vertical post houses are poteaux en terre ("posts-in-the-ground"), where the walls made of upright wooden posts do not support the floor. The floor is supported by separate stone pillars. As the wooden posts were partially set into dirt, the walls of such buildings were extremely vulnerable to flood damage, termites and rot. Three of the five surviving poteaux en terre houses in the nation are in Ste. Genevieve. The other two are located in Pascagoula, Mississippi and near Natchitoches, Louisiana.

Most of the oldest buildings in the city are poteaux sur solle ("posts-on-a-sill"). One of the oldest structures is the Louis Bolduc House built in 1792, which has been designated as a National Historic Landmark. Louis Bolduc originally built a smaller house in 1770 at Ste. Genevieve's first riverfront location. Although much of the house was severely damaged by flooding, parts were dismantled and moved north as the community developed the new site in 1785. Bolduc incorporated these materials into his new and larger house, built in 1792–1793. The three large ground-floor rooms expressed Bolduc's wealth. Other structures of note are the 1806 La Maison de Guibourd Historic House, the 1818 Felix Vallé House State Historic Site, the 1792 Beauvais-Amoureux House, the 1790s Bequette-Ribault House, and the 1808 Old Louisiana Academy, all of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Culture

[edit]For decades, Ste. Genevieve was primarily an agricultural community. The habitants raised chiefly wheat and corn (maize), as well as tobacco. They produced more wheat than residents of St. Louis, and their grain products were shipped south, critical to survival of the French community at New Orleans, which had the wrong climate to cultivate such grains.

The village followed traditional practices: most of the townspeople lived on lots in town. They farmed land held in a common large field. This land was assigned and cultivated in the French style, in long, narrow strips that extended back from the river to the hills (at the first location) so that each settler would have some waterfront. Only the exterior of the Grand Champ (Big Field) was fenced, but each owner of land was responsible for fencing his portion, to keep out livestock.[13] The habitants used the same types of implements and plows as did farmers in 18th-century France. They used teams of oxen to pull the wheeled plows.

After the Louisiana Purchase in 1804, Anglo-Americans as well as German immigrants migrated to the village. It became more oriented to trade and merchants, but villagers retained many of their French cultural ways. The Sisters of St. Joseph, a French teaching order, established a convent in the town, whose sisters taught in a Catholic school. The current Ste. Genevieve Catholic Church was built in 1876 and modeled after the Gothic style of those in France. It was the third Catholic church built by the villagers.

Ste. Genevieve continues to celebrate its French cultural heritage with numerous annual events. Among them are La Guiannée, a celebration associated with Christmas; French Fest; Jour de Fête;[14] King's Ball, and many others. Heritage tourism is important to the economy.

Late 19th century to present

[edit]By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Ste. Genevieve also had numerous lime kilns and quarries, important to the industrialization of nearby cities. The city had numerous African-American families who had long been residents of the community, including people of color of partial French and German ancestry. Like the ethnic European French, most of these African-American families were members of the Catholic church in the town, and some were educated and property owners. Some had also been French speakers in the colonial period.[15]

As the lime kilns and quarries were expanded, African-American migrant workers, mostly men, came from Tennessee, Mississippi, and Arkansas to take jobs in these industries. They tended to belong to Protestant sects, if they were religiously affiliated. From quite different cultural backgrounds, the two groups of African Americans did not intermingle much. The migrant workers lived in poorer areas of town or outside in company housing. They tended to congregate in a neighborhood referred to as The Shacks.[15]

Race riot of 1930

[edit]By 1930 Ste Genevieve had about 2662 residents, of whom 170 were African American and the remainder European American. Another 170 African Americans lived outside the town in the county, closer to the work sites. The riot was a four day disturbance, long shrouded in secrecy, during which vigilantes drove away most of the town's black residents, many of whom were recent arrivals recruited to work in local lime kilns and stone quarries.

Greene, Kremer and Holland (1993) state, “In 1930 state troopers were twice called into the little town of Ste. Genevieve to prevent a triple lynching. The entire black population, with the exception of two families, left town after the threatened lynchings.”[16]

The "French Connection"

[edit]The Ste. Genevieve-Modoc Ferry across the Mississippi River to Illinois is nicknamed the "French Connection". This refers to the 1971 film of the same name and, more directly, to the ferry's link to other French colonial sites in the area, such as Fort de Chartres and Fort Kaskasia State Historic Sites, and the Pierre Menard home. It runs daily year-round, unless the river is flooding. It can carry vehicles, walk-on passengers, and travelers with bicycles.

Geography

[edit]Ste. Genevieve is located along the west bank of the Mississippi River near the Illinois state line along Interstate 55, U.S. Route 61, and Missouri Route 32, approximately 46 mi (74 km) south-southeast of St. Louis and 196 mi (315 km) north-northwest of Memphis, Tennessee.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 4.11 square miles (10.64 km2), of which 4.10 square miles (10.62 km2) is land and 0.01 square miles (0.03 km2) is water.[17] It has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen: Cfa) and average monthly temperatures range from 32.4 °F (0.2 °C) in January to 78.6 °F (25.9 °C) in July. [1]

Nearby communities

[edit]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 718 | — | |

| 1860 | 1,277 | 77.9% | |

| 1870 | 1,521 | 19.1% | |

| 1880 | 1,422 | −6.5% | |

| 1890 | 1,586 | 11.5% | |

| 1900 | 1,707 | 7.6% | |

| 1910 | 1,967 | 15.2% | |

| 1920 | 2,046 | 4.0% | |

| 1930 | 2,662 | 30.1% | |

| 1940 | 2,787 | 4.7% | |

| 1950 | 3,992 | 43.2% | |

| 1960 | 4,443 | 11.3% | |

| 1970 | 4,468 | 0.6% | |

| 1980 | 4,481 | 0.3% | |

| 1990 | 4,411 | −1.6% | |

| 2000 | 4,476 | 1.5% | |

| 2010 | 4,410 | −1.5% | |

| 2020 | 4,999 | 13.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] 2020[19] | |||

2010 census

[edit]As of the census[20] of 2010, there were 4,410 people, 1,824 households, and 1,087 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,075.6 inhabitants per square mile (415.3/km2). There were 2,018 housing units at an average density of 492.2 per square mile (190.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 95.78% White, 1.59% Black or African American, 0.39% Native American, 0.63% Asian, 0.02% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 0.18% from other races, and 1.41% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.18% of the population.

There were 1,824 households, of which 27.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.6% were married couples living together, 11.5% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.4% had a male householder with no wife present, and 40.4% were non-families. 34.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.28 and the average family size was 2.94.

The median age in the city was 43 years. 21.8% of residents were under the age of 18; 8.2% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 22.2% were from 25 to 44; 27.3% were from 45 to 64; and 20.5% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.4% male and 51.6% female.

2000 census

[edit]As of the census[4] of 2000, there were 4,476 people, 1,818 households, and 1,154 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,076.7 inhabitants per square mile (415.7/km2). There were 1,965 housing units at an average density of 472.7 per square mile (182.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 96.07% White, 2.14% African American, 0.58% Native American, 0.31% Asian, 0.25% from other races, and 0.65% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.12% of the population.

There were 1,818 households, out of which 27.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.7% were married couples living together, 10.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.5% were non-families. 32.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 19.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.29 and the average family size was 2.90.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 21.9% under the age of 18, 7.7% from 18 to 24, 25.0% from 25 to 44, 21.8% from 45 to 64, and 23.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.8 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $33,929, and the median income for a family was $43,125. Males had a median income of $31,546 versus $19,804 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,361. About 7.8% of families and 9.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.8% of those under age 18 and 10.2% of those age 65 or over.

Education

[edit]Public education in Ste. Genevieve is administered by Ste. Genevieve R-II School District.[21]

Ste. Genevieve has a public library, the Ste. Genevieve Branch Library.[22]

Government

[edit]| Year | Democratic | Republican | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 36.20% 660 | 62.40% 1,138 | 1.50% 27 |

| 2016 | 36.00% 673 | 56.20% 1,069 | 6.70% 126 |

| Mayor | Took office | Left office | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|

Firmin A. Rozier Sr.

|

1851[24] | He raised a company of troops for the Mexican-American War, and was later appointed major-general of the Southeast Missouri Militia. In 1856, he was elected to the Missouri House of Representatives. In 1872, he was elected to the Missouri senate. He was also a bank president. His brother Charles Constant Rozier was also mayor of Ste. Genevieve. | |

Charles Constant Rozier

|

1860 | 1862[25] | He became a member of the board of regents for State Normal School.[26] |

Charles Constant Rozier

|

1872[25] | (He previously served as mayor.) | |

Anton Samson

|

|||

| Joseph Weiler | c. 1917–1918 | ||

Peter H. Weiler

|

1930 | He was mayor during the October 1930 race riot, a four-day disturbance by whites that resulted in most African Americans being expelled from the town. He twice requested National Guard assistance from the governor to reduce confrontations. Longtime residents and property owners were invited to return, but the threats of violence disrupted the African-American community. It remained disproportionately small compared to early decades.[15] | |

| Ellis J. LaHay | 1945 | 1947 | |

| Francis J. Grieshaber | 1947 | 1951 | |

| Max Okenfuss | 1951 | 1953 | |

| Ralph Beckman | 1953 | 1955 | |

William Scherer

|

1955 | 1971 | |

| Ervin M. Weiler | 1971 | 1975 | |

Larry J. Forhan

|

1975 | c. 1978 | He also served as mayor of Scott City, Missouri, 1992–1996.[27][28] |

| Ervin M. Weiler | c. 1978 | 1985 | (He previously served as mayor.) |

| Richard M. Huck | 1985 | c. 1989 | |

| William E. Anderson | c. 1997 | ||

| Michael Jokerst[29] | c. 1997 | c. 1998 | |

| Ralph Beckerman[30] | c. 1998 | 1999 | |

| Kathy Waltz[31] | 2002 | ||

| Richard Greminger[32] | 2002 | 2017 | |

| Paul Hassler[33] | 2017 |

Media

[edit]The Ste. Genevieve Herald[34] is a weekly newspaper that has served Ste. Genevieve County since May 1882.

Notable people

[edit]- Steve Bieser - Head Baseball Coach at the University of Missouri

- Lewis Vital Bogy - U.S. Senator from Missouri

- Henry Brackenridge - lived here as a boy with an ethnic French family, and wrote about them, the town, and the Osage in his memoir

- Firmin Rene Desloge - nephew of Jean Ferdinand Rozier, arrived 1822, progenitor of the Desloge Family in America[35]

- Augustus Caesar Dodge - US Senator from Iowa

- Henry Dodge - US Senator from Wisconsin

- Laurent Durocher - member of the Michigan Senate and House of Representatives

- Pierre Gibault - 18th-century French Jesuit priest and missionary

- Lewis Fields Linn - U.S. Senator from Missouri

- William Pope McArthur - American naval officer and hydrologist

- Robert Moore - Oregon pioneer and founder of Linn City, Oregon

- Charles Nerinckx - founder of the Sisters of Loretto religious order

- Nathaniel Pope - US Representative from the Illinois Territory

- Philippe-François de Rastel de Rocheblave - French military and French-Canadian political figure in the 18th century

- Prospect K. Robbins - surveyor who established the Fifth Principal Meridian[36]

- Frank Rolfe - real estate investor; owner of the Ste. Genevieve Academy

- Jean Ferdinand Rozier - 19th-century businessman and partner of artist and naturalist John James Audubon

- François Vallé - 18th-century pioneer, mine owner, and land-holder

- John Hardeman Walker - US Congressman

- Matthew E. Ziegler - American Artist

Gallery of notable people

[edit]-

Felix Rozier

(1822–1908),

prominent business figure whose father, Jean Ferdinand Rozier, became business partners with John James Audubon

Historical flags

[edit]-

Flag of New France

to 1763 -

Flag of New Spain

1763–1803 -

15 star-15 stripe US flag

1804–1818 -

Flag of Missouri

from 1913

Sister cities

[edit]Galleries

[edit]Recent

[edit]-

Louis Bolduc House Museum, c. 1785

-

Maison Bequette-Ribault, c. 1789

-

Felix Vallé State Historic Site, c. 1818

-

John Price "Old Brick" Building, c. 1804

-

Joseph Bogy House, c. 1870

-

Dr. Fenwick House, c. 1805

-

Southern Hotel, c. 1820

-

Jesse Robbins house, c. 1867

-

A German style building

-

A Victorian house

-

A small shop

-

The Lasource-Durand Cabin

-

An interesting house

-

A house near Gabouri Creek

-

An old house

-

A 19th-century house

-

Memorial Cemetery, established 1787 and Missouri's oldest

-

The tug Holly J

Archival

[edit]-

Indian trading post

Shaw House

MDNR -

Cabin c. 1936

Bauvais-Amoureux House

MDNR -

Circa 1937

Maison Bequette-Ribault -

Sleeping quarters

Bolduc House

NSCDA/MO -

French style barn

Jean Baptiste Vallé House -

City's first post office

See also

[edit]- Louisiana (New France)

- Louisiana Purchase

- Illinois Country

- Ohio Country

- New France

- New Spain

- French in the United States

- Timeline of New France history

- Three Flags Day

- A few acres of snow

- French colonization of the Americas

- French colonial empire

- List of North American cities founded in chronological order

- Sainte Geneviève

- List of commandants of the Illinois Country

- Historic regions of the United States

References

[edit]- ^ "The Ste. Genevieve Herald tagline "Printed in the Mother City of the West since 1882"". Retrieved September 10, 2014.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Ste. Genevieve, Missouri

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Explore Census Data".

- ^ Carl J. Ekberg, Colonial Ste. Genevieve: An Adventure on the Mississippi Frontier, Gerald, MO: The Patrice Press, 1985, pp. 15-20

- ^ Ekberg (1985), Colonial Ste. Genevieve, p. 25

- ^ Ekberg (1985), Colonial Ste. Genevieve, p. 87

- ^ a b Ekberg (1985), Colonial Ste. Genevieve, pp. 87-104

- ^ Ekberg (1985), Colonial Ste. Genevieve, p. 177

- ^ "The 1852 Ste. Genevieve Stampede". Slave Stampedes on the Southern Borderlands. Dickinson College. June 21, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ Ekberg (1985), Colonial Ste. Genevieve, p. 130-132

- ^ Jour de Fête

- ^ a b c Huber, Patrick (January 2021). "Remembering the Ste. Genevieve Race Riot of 1930: Historical Memory and the Expulsion of African Americans from a Small Missouri Town". Missouri Historical Review.

- ^ "Comments". justice.tougaloo.edu. 1993. p. 153. Archived from the original on July 14, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data".

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ^ "Homepage". Ste. Genevieve County R-Ii School District. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ "Missouri Public Libraries". PublicLibraries.com. Archived from the original on June 10, 2017. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ "Election Information". www.stegencounty.org.

- ^ "The Bolduc House Museum". Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ a b "Welcome to Ste. Genevieve County, Missouri: Biographies "R"". Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ History of Southeast Missouri: Embracing an Historical Account of the Counties of Ste. Genevieve, St. Francois, Perry, Cape Girardeau, Bollinger, Madison, New Madrid, Pemiscot, Dunklin, Scott, Mississippi, Stoddard, Butler, Wayne and Iron. Chicago: The Goodspeed Publishing Company. 1888. p. 611.

- ^ "Larry J. Forhan". February 17, 2003. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ "Larry Forhan". Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ Jim Grebing (ed.). Official Manual State of Missouri 1997-1998. p. 843.

- ^ Julius Johnson (ed.). Official Manual State of Missouri 1999-2000. p. 823.

- ^ "Ste. Genevieve to get aircraft repair facility". Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ "Welcome to the City of Ste. Genevieve!". Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ "City of Ste. Genevieve MO". www.stegenevieve.org.

- ^ Ste. Genevieve Herald Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Christopher Desloge, Desloge Chronicles - Tale of Two Continents, lulu, 2010

- ^ "Surveyors Challenge" Archived 2010-07-06 at the Wayback Machine, Big Muddy, Southeastern Missouri University

Further reading

[edit]- Ekberg, Carl J. Colonial Ste. Genevieve: An Adventure on the Mississippi Frontier (Gerald, MO: The Patrice Press, 1985)

- Ekberg, Carl J. François Vallé And His World: Upper Louisiana Before Louis and Clark (University of Missouri Press, 2002) 316 pp.

- Stepenoff, Bonnie. From French Community to Missouri Town: Ste. Genevieve in the Nineteenth Century (University of Missouri Press, 2006) 232 pp.

External links

[edit]- United states 2010 census map

- Foundation for Restoration of Ste. Genevieve, Inc. Guibourd Historic House & Mecker Research Library

- Ste. Genevieve County Historical and Genealogical Resources

- Sainte Genevieve Chamber of Commerce

- Felix Vallé State Historic Site Missouri Department of Natural Resources

- Ste. Genevieve Herald

- Historic maps of Ste. Genevieve in the Sanborn Maps of Missouri Collection at the University of Missouri

- Sainte Geneviève National Historical Park (NPS, est. 2019)