The Archives of the Planet (French: Les archives de la planète) was a project undertaken from 1908 to 1931 to photograph human cultures around the world. It was sponsored by French banker Albert Kahn and resulted in 183,000 meters of film and 72,000 color photographs from 50 countries. Beginning on a round-the-world trip that Kahn took with his chauffeur, the project grew to encompass expeditions to Brazil, rural Scandinavia, the Balkans, North America, the Middle East, Asia, and West Africa, among other destinations, and documented historical events such as the aftermath of the Second Balkan War, World War I in France, and the Turkish War of Independence. It was inspired by Kahn's internationalist and pacifist beliefs. The project was halted in 1931 after Kahn lost most of his fortune in the stock market crash of 1929. Since 1990, the collection has been administered by the Musée Albert-Kahn, and most of the images are available online.

History

[edit]

In November 1908, Albert Kahn, a French banker from a Jewish family who had made a fortune by speculating on emerging markets,[1] set off on a round-the-world-trip with his chauffeur, Alfred Dutertre.[2] Dutertre took photographs of the places they visited using a technique called stereography, which was popular with travelers as its photographic plates were small and required short exposure times.[1] He also brought a Pathé film camera and a few hundred color plates.[2] They stopped first in New York City, followed by Niagara Falls and Chicago. After a brief stay in Omaha, Nebraska, Dutertre and Kahn went on to California, where Dutertre captured images of the ruins from the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.[3] On 1 December, the two boarded a steamship to Yokohama in Japan. On the way, they spent nineteen hours on a layover in Honolulu, Hawaii.[4] They crossed the International Date Line on 12 December and arrived at Yokohama six days later.[5] After Japan, their voyage in Asia took them through China, Singapore, and Sri Lanka.[6]

When he returned to France, Kahn hired two professional photographers, Stéphane Passet and Auguste Léon, the latter of whom likely[7] came with Kahn on a trip to South America in 1909,[1] on which Rio de Janeiro and Petrópolis were photographed in color.[7] Other early expeditions included a visit by Léon to rural Norway and Sweden in 1910.[8]

The Archives of the Planet officially began in 1912, when Kahn appointed geographer Jean Brunhes to direct the project, in exchange for a chair at the Collège de France endowed by Kahn. Stereography was replaced with the autochrome process, which yielded color photographs but demanded long exposure times, and motion pictures were added.[9] Kahn conceived of the project as an "inventory of the surface of the globe inhabited and developed by man as it presents itself at the start of the 20th Century",[10] and hoped that the project would further his internationalist and pacifist ideals, as well as document disappearing cultures.[11] The philosopher Henri Bergson, a close friend of Kahn's, was a strong influence on the project.[12]

In 1912, Passet was sent to China (the first official mission of the project)[13] and Morocco, while Brunhes went with Léon to Bosnia-Herzegovina and then to Macedonia in 1913. The expedition was interrupted by the Second Balkan War; when the war ended, Passet traveled to the region to document its aftermath.[14]

Léon, the longest-serving photographer on the project, went on two trips to Great Britain in 1913, photographing London landmarks such as Buckingham Palace and St. Paul's Cathedral, as well as scenes in rural Cornwall. In the same year, Marguerite Mespoulet, the only woman to serve as a photographer for the Archives, travelled to the west of Ireland.[15] After Britain, Léon went on to Italy, accompanied by Brunhes.[16] In the same year, Passet returned to Asia. He went to Mongolia first, and then on to India, where in January 1914 the British authorities denied him passage through the Khyber Pass to Afghanistan, where he wanted to photograph the Afridi people.[17] Later that year, army officer and volunteer photographer Léon Busy arrived in French Indochina, where he would stay until 1917.[18]

The outbreak of World War I forced a change in the project's focus; Kahn, a French patriot despite his internationalist leanings, sent his photographers to capture the effects of the war on France and allowed the photographs to be used as propaganda,[19] although most of the photographers were kept away from the frontline.[20] Kahn negotiated a deal in 1917 with the army for two of their photographers to help capture images for his archive. Photographs from the war would eventually make up 20% of the collection.[21]

In the 1920s, photographers were sent to Lebanon, Palestine, and Turkey in the Middle East, where they documented the French occupation of Lebanon and the Turkish War of Independence.[22] Frédéric Gadmer was sent to Weimar Germany in 1923; among the scenes he shot was the aftermath of a failed separatist insurrection in Krefeld.[23] The last trip to India was made in 1927, where photographer Roger Dumas captured the golden jubilee of Jagatjit Singh, the ruler of Kapurthala State. The previous December, Dumas had been in Japan for the funeral of Emperor Yoshihito.[24]

Kahn's photographers returned to the Americas several times in the 1920s. Lucien Le Saint made films of French fisherman in the North Atlantic in 1923, and Brunhes and Gadmer travelled for three months across Canada in 1926, visiting Montreal, Winnipeg, Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver, among other places.[25] In 1930, Gadmer mounted the project's first and only major expedition to sub-Saharan Africa, to the French colony of Dahomey (modern-day Benin).[26]

By the time that the project was halted in 1931, in the aftermath of the stock market crash of 1929 that bankrupted Kahn, Kahn's cameramen had visited 50 countries and collected 183,000 meters of film, 72,000 autochrome color photographs, 4,000 stereographs, and 4,000 black-and-white photographs.[10][27]

Contents

[edit]

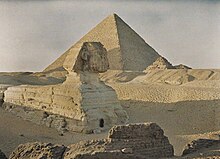

David Okuefuna describes the Archive as a "monumentally ambitious attempt to produce a photographic record of human life on Earth",[28] and the contents of the Archive are highly varied in subject.[15] On the early expeditions to Europe, Brunhes instructed the photographers to capture the geography, architecture, and local culture of the places they visited, but also gave them the freedom to photograph other things that caught their eyes.[29] Images in the Archive include landmarks like the Eiffel Tower,[30] the Great Pyramid of Giza,[31] Angkor Wat,[32] and the Taj Mahal,[33] as well as numerous portraits of working-class people in Europe[34] and of members of traditional societies in Asia and Africa.[35] In many cases, Kahn's operators captured some of the earliest color photographs of their destinations.[36] Due to the long exposure time required by the autochrome process, the photographers were largely limited to shooting stationary or posed subjects.[37]

About a fifth of the photographs in the Archive were concerned with the First World War.[21] These included images of the home front, military technology like artillery guns and ships, portraits of individual soldiers (including some from France's colonial empire), and buildings damaged by shelling.[38] Only a handful of images explicitly depict dead soldiers.[39]

Some of the content in the Archives was controversial, in particular a film shot by Léon Busy of an adolescent Vietnamese girl undressing.[40] Busy had instructed the girl to go through her daily dressing ritual; he shot the film out of focus to obscure her nudity.[41] Other footage shot in Casablanca in 1926 featured prostitutes baring their breasts.[42]

The Archives also include thousands of portrait photographs, mostly shot at Kahn's estate in Boulogne-Billancourt. Subjects include statesmen such as British prime minister Ramsay MacDonald and French prime minister Léon Bourgeois, British physicist J. J. Thomson, French writers Colette and Anatole France, Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore, and American aviator Wilbur Wright, among many others.[43]

The collection has been administered by the Musée Albert-Kahn since 1990, which has made most of images available to the public online.[44]

Photographers

[edit]- Léon Busy (1874–1950) was a French army officer who volunteered for the Archives on the strength of winning first prize in the Société française de photographie's photography competition.[45]

- Paul Castelnau (1880–1944) and Fernand Cuville (1887–1927) were French soldiers who served as photographers during World War I.[46] Castelnau later became a member of the French Geographic Society.[47]

- Roger Dumas (1891–1972) took photographs and films in Japan and India in 1926 and 1927.[48]

- Alfred Dutertre was Kahn's chauffeur who accompanied him on his first round-the-world trip in 1908, taking the earliest photographs in the Archives.[2]

- Frédéric Gadmer (1878–1954) was sent to Germany in 1923,[23] and to Canada in 1926,[49] ultimately becoming one of the Archives' most experienced photographers.[50]

- Lucien Le Saint (1881–1931) was a cinematographer who shot motion picture films for the project.[49]

- Auguste Léon (1857–1942) was the longest-serving photographer on the project.[29] From Bordeaux, he had previously worked as a postcard photographer.[7] He also oversaw work at the photocinematographic laboratory for the project.[51]

- Marguerite Mespoulet (1880–1965) was an academic and amateur photographer who was the only woman to take pictures for the Archives.[52]

- Stéphane Passet (1875 – c. 1943[53]) was one of the first photographers hired by Kahn,[1] and undertook an expedition to the Balkans.[54]

- Camille Sauvageot was a motion-picture operator who served between 1919 and 1932. He later worked on the 1949 film Jour de fête.[55]

Gallery

[edit]-

Eiffel Tower and the Trocadéro (Paris, 1912)

-

Porte Saint-Denis (Paris, 1914)

-

Family (Paris, 1914)

-

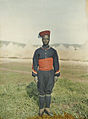

Senegalese sniper (Fez, Morocco, 1913)

-

Market scene (Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina, 1912)

-

Market scene (Krusevac, Serbia, 1913)

-

Wooden houses in Beyoğlu (Istanbul, Turkey, 1912)

-

Inner Mongolia, 1912

-

Buddhist lama (Mongolia, 1913)

-

Prisoner (Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 1913)

-

Sadhus (Bombay, India, 1913)

-

Sadhu and brahmin (Lahore, Pakistan, 1914)

-

Temple officiant (Ahmedabad, India, 1913)

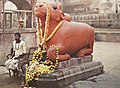

-

Bull statue (Varanasi, India, 1914)

See also

[edit]- Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, a photographer who made color photographs of the Russian Empire in the early 20th century

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d de Luca 2022, pp. 265–267.

- ^ a b c Okuefuna 2008, p. 81.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, p. 84.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, p. 185.

- ^ de Luca 2022, p. 267.

- ^ a b c Okuefuna 2008, p. 85.

- ^ de Luca 2022, p. 273.

- ^ de Luca 2022, pp. 267–268.

- ^ a b Lundemo 2017, pp. 218–219.

- ^ de Luca 2022, p. 261.

- ^ Amad 2010, pp. 99–101.

- ^ Amad 2010, p. 51.

- ^ de Luca 2022, pp. 275–276.

- ^ a b Okuefuna 2008, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, pp. 191–194.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, pp. 229–233.

- ^ de Luca 2022, pp. 262–263.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, p. 131.

- ^ a b de Luca 2022, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Johnson 2012, p. 92.

- ^ a b Okuefuna 2008, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, pp. 87–87.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, pp. 286–287.

- ^ de la Bretèque 2001, p. 156.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, p. 13.

- ^ a b Okuefuna 2008, p. 20.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, pp. 29.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, p. 300.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, p. 258.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, p. 222.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, pp. 28–80.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, pp. 208–211, 242–253, 306–309.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, pp. 222, 287, 300.

- ^ Amad 2010, p. 55.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, pp. 140–179.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, p. 175.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, p. 232.

- ^ Amad 2010, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, pp. 310–319.

- ^ de Luca 2022, p. 263.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, p. 229.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, p. 134.

- ^ Bloom 2008, p. 169.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, p. 194.

- ^ a b Okuefuna 2008, p. 86.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, p. 286.

- ^ Bloom 2008, p. 168.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, p. 99.

- ^ Okuefuna 2008, pp. 99–101.

- ^ Amad 2010, p. 307.

Works cited

[edit]- Amad, Paula (2010). Counter-Archive: Film, the Everyday, and Albert Kahn's Archives de la Planète. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13500-9.

- de la Bretèque, François (April–June 2001). "Les archives de la planète d'Albert Kahn". Vingtième Siècle. Revue d'histoire (in French) (70): 156–158. doi:10.2307/3771719. JSTOR 3771719.

- Bloom, Peter J. (2008). French Colonial Documentary: Mythologies of Humanitarianism. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-4628-9.

- Johnson, Brian (Summer 2012). "Review: Middle East: the Birth of Nations—Albert Kahn's Archive of the Planet". Review of Middle East Studies. 46 (1): 92–93. doi:10.1017/S2151348100003062. JSTOR 41762489.

- de Luca, Tiago (2022). "A Disappearing Planet". Planetary Cinema: Film, Media and the Earth. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 259–298. doi:10.2307/j.ctv25wxbjs.11. JSTOR j.ctv25wxbjs.11. S2CID 245373654.

- Lundemo, Trond (2017). "Mapping the World: Les Archives de la Planète and the Mobilization of Memory". Memory in Motion: Archives, Technology and the Social. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 213–236. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1jd94f0.12. ISBN 9789462982147. JSTOR j.ctt1jd94f0.12.

- Okuefuna, David (2008). The Dawn of the Color Photograph: Albert Kahn's Archives of the Planet. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13907-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Amad, Paula (2001). "Cinema's 'Sanctuary': From Pre-Documentary to Documentary Film in Albert Kahn's "Archives de la Planète" (1908–1931)". Film History. 13 (2): 138–159. doi:10.2979/FIL.2001.13.2.138. JSTOR 3815422.

- Bourguignon, Hélène (January–March 2009). "Les Archives de la planète". Vingtième Siècle. Revue d'histoire (in French) (101): 203–207. JSTOR 20475560.

- Jakobsen, Kjetil Ansgar; Bjorli, Trond Erik, eds. (2020). Cosmopolitics of the Camera: Albert Kahn's Archives of the Planet. Intellect Books. ISBN 978-1-78938-190-0.

- McGrath, Jacqueline (30 March 1997). "A Philosophy in Bloom". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- Winter, Jay (2006). Dreams of Peace and Freedom: Utopian Moments in the Twentieth Century. Yale University Press.