The Serapion Brethren (Die Serapionsbrüder) is the name of a literary and social circle, formed in Berlin in 1818 by the German romantic writer E. T. A. Hoffmann and several of his friends. The Serapion Brethren also is the title of a four-volume collection of Hoffmann's novellas and fairytales that appeared in 1819, 1820, and 1821.

The literary circle

[edit]Seraphin Brethren

[edit]In 1814, Hoffmann returned to Berlin from Dresden and Leipzig, where he had been working as an orchestra conductor and opera director, to return to work as a Prussian civil servant. In that year, he and a group of friends formed an association for the purpose of reading from and discussing works of literature (primarily their own). The group first met on October 12, which happened to be the feast day of Saint Seraphin of Montegranaro. The friends therefore decided to refer to their group as an “order” and to give it the name The Seraphin Brethren [Die Seraphinenbrüder]. After about two years of gatherings at Hoffmann's home or the Café Manderlee on the famous boulevard Unter den Linden, the circle gradually dissolved, partly, it is thought, because of the departure of one of its members, Adelbert von Chamisso, for a sailing trip around the world with the Russian Rurik Expedition, which had been organized to find a Northwest Passage (Kremer, 1999, 165).

Serapion Brethren

[edit]On November 13, 1818, Hoffmann's publisher gave him a sizable advance on the publication of a multivolume collection of his novellas and fairytales. To celebrate this happy event (Hoffmann was quite impecunious at the time), the author invited his friends from the old Seraphin Brethren to his home on November 14 for the purpose of celebrating the advance and reviving the literary group. Another reason for celebration was the return of Chamisso from his travels. Hoffmann's wife Micha brought the calendar, and the date was seen to be the feast day of Saint Serapion. Accordingly, the old order was rechristened The Serapion Brethren (Die Serapionsbrüder) (the Catholic list of saints [see “Catholic Online” at WWW.catholic.org]) shows eleven Saint Serapions; the one after which the group was named was probably Saint Serapion the Sindonite, a fourth-century Egyptian hermit and monk) (Kaiser 1988, 64; Pikulik 2004, 135).

The Serapion Brethren included the following members:

- Hoffmann's lifelong friend and occasional benefactor Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel

- Hoffmann's colleague in the civil service and first biographer Julius Eduard Hitzig

- Poet Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué

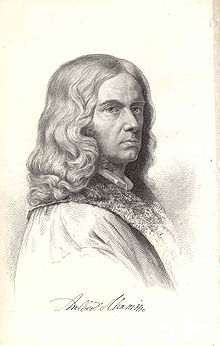

- Novelist Adelbert von Chamisso

- Dramatist, novelist, and merchant Karl Wilhelm Salice-Contessa

- Prussian military officer Friedrich von Pfuel

- Physician David Ferdinand Koreff

- Theologian Johann Georg Seegemund

Others participated from time to time in the group's meetings as guests.

The book title

[edit]In February 1818, the Berlin publisher Georg Reimer offered to publish a compilation of Hoffmann's previously published but scattered novellas and fairytales. Hoffmann suggested uniting the disparate works by presenting them in a fictional framework of readings and conversations among a group of friends in the manner of Ludwig Tieck’s Phantastus (Kremer 1999, 164) (and, although Hoffmann did not say this, in the manner of Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron, albeit in an urban rather than a pastoral setting). For the collection, Hoffmann first suggested to Reimer the title The Seraphin Brethren. Collected Novellas and Fairytales, after the old literary group. Once the group was reconstituted, however, Hoffmann dropped the subtitle and called the compilation simply The Serapion Brethren (Segebrecht 2001, 1213).

In eight meetings, the friends in the fictional framework narrative, Ottmar, Theodor, Lothar, Cyprian, Vinzenz, and Sylvester, orally present a total of 28 stories (only 19 have titles) and comment in some detail on their quality and on whether or not they adhere to a certain “Serapion Principle” that becomes clear to the reader as the narrative progresses. Attempts have been made, especially in older scholarly works, to assign the names of some of the real Serapion Brethren to the fictitious ones. Ellinger (1925, 40), for example, sees Ottmar, Theodor, Sylvester, and Vinzenz, as Hitzig, Hoffmann, Contessa, and Koreff, respectively. In reality, of course, all the narrators are Hoffmann himself, who, after all, was writing fiction (Steinecke 1997, 115).

References

[edit]- Ellinger G., editor. E.T.A. Hoffmanns Werke, Vol. 5, Berlin and Leipzig, Deutsches Verlagshaus Bong & Co., 1925.

- Ewing, Alexander (translator), Hoffmann, Ernst Theodor Wilhelm, The Serapion Brethren (in two volumes), G. Bell & Sons: London, 1886-92.

- Feldges B. & Stadler U., editors. E.T.A. Hoffmann: Epoche-Werk-Wirkung, Munich: C.H. Beck’sche Elementarbücher, 1986. ISBN 3-406-31241-1

- Kaiser G.R., editor. E.T.A. Hoffmann (Sammlung Metzler, Vol. 243), Stuttgart: J.B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1988. ISBN 3-476-10243-2

- Kremer D. E.T.A. Hoffmann. Erzählungen und Romane, Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag, 1999. ISBN 3-503-04932-0

- Pikulik L. Die Serapions-Brüder. In: Saße G., editor. Interpretationen. E. T. A. Hoffmann. Romane und Erzählungen, Stuttgart: Philipp Reclam jun., 2004. ISBN 3-15-017526-7

- Segebrecht W., editor. E.T.A. Hoffmann. Die Serapions-Brüder. In: Steinecke H. & Segebrecht W., editors. E.T.A. Hoffmann. Sämtliche Werke in sechs Bänden, Vol. 4, Berlin: Deutscher Klassiker Verlag, 2001. ISBN 3-618-60880-2

- Steinecke H. E.T.A. Hoffmann, Stuttgart: Philipp Reclam jun., 1997. ISBN 3-15-017605-0