The following is a timeline of the history of the city of Indianapolis, Indiana, United States.

19th century

[edit]1800s–1840s

[edit]- 1816

- The U.S. Congress authorizes a state government for Indiana and donates federal land to establish a permanent seat of government for the new state.[1]

- 1818

- Under the terms of the Treaty of St. Mary's, the Delaware Nation cede their lands in Indiana to the U.S. government and agree to leave central Indiana by 1821.[2]

- 1820

- On January 11 the Indiana General Assembly authorizes a selection committee to choose a permanent site for the new state capital. On June 7 the commissioners select four sections of land along west fork of the White River, on its eastern bank, two miles (3.2 km) northwest of Indiana's geographic center.[3][4]

- 1821

Plat of the Town of Indianapolis from December 1821

Sign on the Indianapolis City County Building commemorating the founding of Indianapolis - On January 6 the Indiana General Assembly ratifies the site selection on the White River in central Indiana as the permanent state capital of Indiana and names it Indianapolis, the state's new seat of government.[5][6]

- Alexander Ralston and Elias Pym Fordham are appointed to survey the site selected for the new state capital.[7]

- The town's first two justices of the peace are appointed on January 9.[8]

- Several hundred cases of illness and twenty-five fatalities, most of them children, are reported in Indianapolis after heavy rains fall during June, July, and August.[9]

- The town's first property lots are offered for sale on October 8.[10]

- Local residents erect the town's first log schoolhouse; however, the town's first permanent school is not established until 1824.[11]

- A town cemetery is established near the White River. The site is renamed Greenlawn Cemetery in 1862.[12]

- Marion County, Indiana, is established on December 31, 1821, with Indianapolis named as the county's seat of government.[13]

- Issac Wilson builds a gristmill, a predecessor to the Acme-Evans Company, along the White River. Archer Daniels Midland acquires the company in 1988, and changes its name to the Acme-Evans/ADM Milling Company. Its downtown buildings are demolished in 1994, after the company moves to the city's south side.[14]

- 1822

- Indianapolis Gazette, the city's first newspaper, begins publication.[15][16]

- Indianapolis's first postmaster is appointed.[17]

- The first election of Marion County government officials is held.[18]

- The state legislature appropriates funds to build state roads to Indianapolis, while the Marion County government begins construction of county roads.[19]

- The first session of the Fifth Judicial Circuit Court in Marion County is held in a local resident's log home.[20]

- A militia is organized in central Indiana.[21]

- The town's first jail is built.[22]

- Methodists organize their first Indianapolis congregation. They meet for worship services in a log structure until their new church is erected in 1829. Wesley Chapel is built in 1846. The congregation's Meridian Street Methodist Episcopal Church, dedicated in 1871, is destroyed by fire in 1904; its replacement is built at Meridian and Saint Clair streets.[23] The congregation merges with the Fifty-first Street Methodist Church in 1945, and the combined congregation erects Meridian Street Methodist Church, which opens in 1952.[24]

- Baptists organize the city's first Baptist congregation on October 10. The group first meets in a log schoolhouse. The First Baptist Church is completed in 1831.[25][26][27] Two replacement churches are destroyed by fire, one in 1861 and the other in 1904. Their replacement, built at Meridian and Vermont streets, is dedicated in 1906;[28] it is vacated in 1960 and a new church is constructed at North College Avenue and 86th Street.[29]

- 1823

- The Western Censor and Emigrant's Guide begins publication. Its name is changed to the Indiana Journal in 1825. It becomes a permanent daily newspaper and is renamed the Indianapolis Daily Journal in 1854. The Journal merges with The Indianapolis Star on June 8, 1904.[30][31]

- The Indiana Central Medical Society is formed to license physicians to practice medicine.[32][33]

- The town's first theatrical performance takes place at a local tavern.[34]

- Presbyterians establish Indianapolis's First Presbyterian Church congregation on July 23. Its first church is completed in 1824. The congregation merges with the Meridian Highlands Presbyterian Church in 1970, establishing the First-Meridian Highland Church congregation.[35][36][37][38]

- The Indianapolis Sabbath School Union is established.[39]

- 1824

- Marion County courthouse is completed; it also houses the Indiana General Assembly until a new Indiana Statehouse is completed in 1835.[40]

- The town's first training school for militia officers and soldiers is established.[41]

- A series of severe spring storms flood waterways and set high water marks for Indianapolis.[42]

- 1825

- Indiana's state government relocates to Indianapolis from Corydon, Indiana, effective January 1.[40]

- A U.S. District Court is established in the city; Benjamin Parke is its presiding judge.[43]

- Indiana State Library is established.[44]

- Indianapolis Journal newspaper begins publication.[15]

- The first Marion County courthouse is completed in January.[45]

- The first session of the state legislature in Indianapolis begins in January at the newly completed county courthouse.[46]

- The Indiana State Library is founded.[47]

- The Marion County Agricultural Society is organized.[48]

- 1826

- The Indianapolis Fire Company, the town's first volunteer fire company, is organized in June.[49]

- The town's first rifle and artillery companies are formed.[50]

- 1827

- A governor's mansion is erected on Governor's Circle. The residence is sold in 1857 and demolished.[51][52]

- 1828

- The town's first cavalry company is organized.[53]

- The Indianapolis Steam Mill Company, the town's first incorporated business, builds a new mill along the White River. The mill is completed in 1831, but it proves unprofitable and closes in 1835.[54]

- The Marion County Temperance Society is formed.[55]

- 1829

- Indiana Colonization Society is formed.[56]

- 1830 – Indiana population estimate: 1,900.[57]

- Indiana Historical Society is organized on December 11. Benjamin Parke serves as its first president.[58][59]

- The Indiana Democrat begins publication and consolidates operations with the Gazette. The Democrat becomes the Indiana State Sentinel in 1841. The Sentinel becomes the town's first permanent daily newspaper in 1851; it is discontinued in 1906.[31]

- The Indianapolis Female School, the town's first school for young women, opens in March.[60]

- 1831

1831 map of Indianapolis in Marion County, originally drawn by surveyor B. F. Morris - Town officials appoint Indianapolis's first board of health when the town experiences its first case of smallpox.[58]

- The steamboat Robert Hanna arrives in town on April 11. After it departs from Indianapolis the boat runs aground along the White River; no steamboat successfully returns to the capital city.[61]

- 1832

- The town is incorporated and local government is placed under the direction of five elected trustees.[62]

- The first election for town officials is held in September. Samuel Henderson serves as first president of the town's board of trustees.[63]

- The state legislature authorizes the establishment of the Marion County Seminary, which opens in 1834.[64][65]

- The town's first foundry is established; it begins operations in 1833.[66]

- 1833

- The town's first market house is built. The structure becomes known as the Indianapolis City Market.[58][67]

- The town's first Church of Christ (Disciples of Christ) congregation is organized. Its first church building is erected in 1837. Christian Chapel, completed in 1852, is renamed Central Christian Church in 1879.[68] The congregation dedicates a new church at Delaware and Walnut Street in 1893.[69]

- 1834

- The town's first brewery is established.[70]

- The State Bank of Indiana is chartered and establishes its main office and one of its first sixteen branch locations in Indianapolis.[65]

- Union Cemetery is established.[71] After additional acreage is acquired, the 25-acre (10 ha) cemetery becomes known as Greenlawn Cemetery in 1862.[72]

- 1835

- Construction of a Greek Revival-style Indiana Statehouse is completed.[73]

- The Indiana State Board of Agriculture is established in February.[74]

- The Marion County Board of Agriculture is formed in June. The first Marion County fair is held on October 30–31.[74]

- The Indianapolis Benevolent Society is established in November.[75]

- The town purchases its first hand engine for its volunteer firefighters.[76]

- The Young Men's Literary Society is established; it is incorporated as the Union Literary Society in 1847.[77]

- 1836

- The Indiana General Assembly appropriates funds to begin construction on the Indiana Central Canal and build rail lines from Madison to Lafayette through Indianapolis as part of the Mammoth Internal Improvement Act.[78][79]

- Indianapolis is incorporated with a revised charter.[80]

- The city's first insurance company is organized on March 15.[81]

- Four constables are sworn in to enforce town ordinances.[82]

- The city's oldest African Methodist Episcopal Church congregation is organized. In 1869 the congregation adopts the name Bethel A.M.E. Church.[57][83]

- 1837

- The National Road arrives in Indianapolis.[84]

- Indianapolis Female Institute opens.[85]

- Marion Guards become Indianapolis's first militia company.[86]

- The town erects a new firehouse on the north side of the Circle.[70]

- The First English Lutheran Church congregation (also known as Mount Pisgah Evangelical Lutheran Church) is organized. Its first church is erected in 1838.[87]

- Holy Cross, the city's oldest Catholic parish, is formed in November. The Chapel of the Holy Cross, the parish's first church, is completed in 1840. Its second church, completed in 1850, is named Saint John the Evangelist Catholic Church. It is replaced with Saint John's Cathedral in 1871.[68][88]

- The town's Episcopal congregation organizes and begins construction of its first Christ Church on the Circle. Christ Church Cathedral, completed in 1859, replaces the earlier church and is built on the same site.[89]

- 1838

- Indianapolis reincorporates with a new charter and a new town council formation.[90]

- The city's Second Presbyterian Church congregation organizes on November 19. Its first church building is dedicated in 1840.[91]

- 1839

- The state's bankruptcy halts Central Canal construction after nine miles (14 km) are opened for traffic.[57]

- The Indiana General Assembly appropriates funds to purchase a home at Illinois and Meridian streets to serve as the official governor's residence. It is sold in 1865 and later demolished.[92]

- 1840 – Indianapolis population: 2,692.[57]

- 1841

- Zion's Church, the city's first German-speaking Evangelical congregation, is organized on April 18. Its first church is dedicated in 1845. The church is renamed Zion Evangelical United Church of Christ in 1957, when it merges with other congregations.[68]

- 1842

- Indianapolis's Methodists divide into two congregations. One group remains at the Methodist church on the Circle; the other establishes Roberts Chapel in 1843.[93]

- 1843

- Roberts Chapel becomes the city's eastside Methodist congregation. Its first church is dedicated in 1846. The congregation dedicates its new church, named Robert Park Methodist Episcopal Church, in 1876.[68]

- 1844

- The state government assumes responsibility for William Willard's private school for the deaf, established in 1843,[57][85] and renames it the Indiana State Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb. Construction of its new facility in Indianapolis is completed in 1850.[94][95]

- Saint Paul's Evangelical Lutheran Church, a German Lutheran congregation, is organized. Its first church is dedicated in 1845.[96]

- The city's first United Brethren Church is organized.[29]

- The town's first Universalist Church Society is organized, but it exists only briefly.[97]

- The Indiana Freeman, an antislavery newspaper, appears in November.[98]

- The Marion County Library is established in the basement of the county courthouse.[99][100]

- 1845

- July 4: Lynching of John Tucker occurs near the intersection of Illinois and Washington streets.

- The city's first Methodist congregation is divided a second time to create a western congregation, whose first church is known as Strange Chapel. The congregation erects Saint John's Methodist Episcopal Church in 1871.[101]

- 1846

- 1847

- Heavy rains from December 1846 cause record flooding in January, the city's most significant flood since 1824. In November 1847 a flood nearly equal to the one in January damages property in Indianapolis and West Indianapolis, the National Road, and the Indiana Central Canal.[104][105]

- Samuel Henderson is elected the city's first mayor on April 24.[57][106]

- Indianapolis voters approve a charter to make Indianapolis an incorporated city effective March 30.[57]

- City voters approve taxes to establish free public schools.[107]

- The Locomotive begins publication on August 16. It discontinues operations in 1861 and consolidates with the Sentinel.[108]

- The Indiana Institute for the Education of the Blind opens in October. Construction of the main building on its new site is completed in 1853. It is demolished in 1909 to make space for a new facility.[85][109]

- Construction is completed on the main building of the Indiana Hospital for the Insane.[85][110]

- Madison and Indianapolis Railroad, the first steam railroad in Indiana, begins operations and arrives in Indianapolis on October 1.[57]

- 1848

- The Central Plank Road Company is chartered to construct plank roads connecting Indianapolis to nearby towns.[111]

- The city's first telegraph lines link Indianapolis to Dayton, Ohio.[112]

- The Indiana Volksblatt, the city's first German-language newspaper, begins publication in September.[15][57] It is discontinued in 1907.[113][114]

- Indianapolis and Bellefontaine Railroad in operation.[115]

- Free Soil Banner begins publication.[116]

- The Indiana Central Medical College is organized on November 1.[117]

- Another smallpox scare alarms city residents.[118]

- 1849

1850s–1890s

[edit]- 1850 – Indianapolis population: 8,091[120]

- Construction on the Grand Lodge of the Free Masons, the city's first public hall, is completed.[121]

- North Western Christian University, renamed Butler University in 1877, receives its charter from the state legislature. The university opens for classes in 1855. The school relocates to Irvington in 1875–76, and moves to a new location, known as Fairview Park, in 1928.[122][123][124]

- The city's first United Brethren in Christ congregation is organized. Its first church opens in 1851.[125]

- Indianapolis Business University is established.[44]

- The Union Track Railway Company Company is organized to erect a connecting line between railroads serving Indianapolis.[111][126]

- 1851

- Indianapolis's first gasworks is completed.[127]

- Indianapolis Gas Light and Coke Company is chartered by the state legislature in March. The company begins supplying city residents with natural gas for lighting in 1852.[128][129]

- The Indianapolis Turngemeinde, the first of the city's German clubs and cultural societies, is established on July 28. It merges with other German clubs and becomes known as the Indianapolis Social Turnverein, or Turners.[130][131]

- The Indiana Female College, established by the city's Methodists, receives its charter from the state legislature.[132]

- The Indianapolis Widows and Orphans Friends' Society, predecessor to the Children's Bureau of Indianapolis, is incorporated. The Society erects the first Indianapolis Widows' and Orphans' Asylum in 1855. It is renamed the Indianapolis Orphans' Asylum in 1875. The orphanage is closed in 1941.[133][134]

- Several members of the city's First Presbyterian Church establish the Third Presbyterian Church congregation, whose first church building is dedicated in 1859. Renamed Tabernacle Presbyterian Church in 1883, the congregation begins construction on a new church in 1886, and in 1921 relocates to 34th Street and Central Avenue, where a new church is dedicated in 1929.[135]

- Members of the city's Second Presbyterian Church organize the Fourth Presbyterian Church congregation, whose first church building is dedicated in 1857. The congregation dedicates a new church in 1874, and erects a new church at Nineteenth and Alabama streets in 1895.[136]

- 1852

- The City Guards militia is organized.[137]

- The Center Township Library opens in the Center Township Trustee's office.[138]

- The McLean Female Seminary, a boarding and day school for girls, is established. In 1865 its facility is sold to the Indiana Female Seminary.[139][140]

- The first Indiana State Fair is held on October 19–25, on the grounds of what becomes known as Military Park, west of downtown Indianapolis.[112][120]

- Indiana and Illinois Central Railway is established.[141]

- The First German Reformed Church of Indianapolis congregation is organized. Their first church is dedicated on June 24.[142]

- 1853

- The Mechanic Rifles militia is organized.[137]

- Indianapolis's first Union Depot, the first of its kind in the United States to serve competing railroad lines, opens on September 28.[143][144] It is demolished in 1887 to make space for the Indianapolis Union Station, a new passenger depot that is completed in 1888.[145]

- Indianapolis and Cincinnati Railroad in operation.[citation needed]

- Indianapolis Union Railway in operation.[citation needed]

- Voters approve a new city charter that provides for an elected mayor and a fourteen-member city council.[90]

- Freie Presse von Indiana, a weekly German-language newspaper, begins publication in Indianapolis.[146]

- The city's free public schools establish operations under a common school system and open for enrollment. The city's first free public high school opens in the old Marion County Seminary;[147] however, it closes in 1858, when the Indiana Supreme Court declares the local school tax unconstitutional.[148]

- The first Bates House hotel opens for business.[149] It is replaced at the turn of the century.[150]

- A new Universalist church congregation is organized in the city. The congregation's First Universalist Church is erected in 1860.[97][151][152]

- Construction begins on Odd Fellows Hall.[85][153] It is completed in 1855.[132]

- The city contracts with the Indianapolis Gas Light and Coke Company to illuminate several blocks of Washington Street with gaslight street lamps.[154]

- 1854

- The city council establishes Indianapolis's first regular, paid police department.[155]

- Indianapolis YMCA is organized.[155]

- The Indianapolis Maennerchor, the city's oldest German-language musical club, is established.[156]

- The Society of Friends (Quakers) organizes the First Friends Church of Indianapolis. The Society builds its first meetinghouse and school in 1856.[157][158]

- 1855

- Construction begins on City Hospital, the city's first hospital. It is completed in 1859.[85][159][160]

- North Western Christian University opens in November.[120]

- Indianapolis, Pittsburgh and Cleveland Railroad in operation.[citation needed]

- Smallpox cases are reported in the city.[161]

- 1856

- The Indiana Republican Party holds its first state convention in Indianapolis.[120]

- The Indianapolis National Guards organize.[137]

- A Hebrew cemetery is established on three acres (1.2 ha), three miles (4.8 km) south of the city's center.[162]

- The Indianapolis Hebrew Congregation organizes on November 2. Its East Market Street temple is dedicated in 1868. A new temple at Saint Joseph (Tenth) and Delaware streets is dedicated in 1899;[163] its Meridian Street temple is dedicated in 1958.[162][164][165]

- Saint Marienkirche, the city's first German-language Catholic parish, is established. Its first church and school open in 1858.[166]

- 1857

- The Metropolitan Theater, the first in the city to be built for that purpose, is completed. The theater opens in 1858 and is later renovated and renamed the Park.[167]

- The City Grays militia is organized.[137]

- Plymouth Congregational Church, the city's first Congregational church, is organized. Its church is dedicated in 1871. The congregation merges with North Congregational Church in 1906 and Mayflower Congregational Church in 1908. The consolidated congregation is renamed the First Congregational Church.[168][169]

- 1858

- The Indianapolis Female Institute, a Baptist-affiliated boarding school and day school for girls, is established. It opens for classes in 1859 and closes in 1872.[170][171]

- After the Supreme Court of Indiana declares a local school tax is unconstitutional, the city's public schools struggle for funding and suspend operations until 1861.[172][148]

- 1859

- The city council members vote to establish the city's first regular, paid fire department, and disband the city's volunteer fire companies.[173][174]

- The City Grays Artillery is organized.[175]

- The city's German-English School is founded. It closes in 1882.[176][177]

- The Sisters of Providence of Saint Mary-of-the-Woods establish Saint John's Academy for Girls, the city's first Catholic school.[85][120] The school closes 1959. Its buildings are demolished between 1959 and 1963.[178] A Catholic boys' school, under the direction of the Brothers of the Sacred Heart, opens in 1867.[179]

- 1860 – Indianapolis population: 18,611[120]

- A rapidly moving tornado passes through southeast Indianapolis on May 29; however, the most significant destruction occurs east and west of the city.[180]

- The city's Independent Zouaves and Zouave Guards militia are organized.[137][175]

- A new location for the state fairgrounds is established on approximately 38 acres (15 ha) along Alabama Street, north of the city.[181]

- The city's second Universalist church is organized.[182]

- Land for a Catholic cemetery, which becomes the Holy Cross and St. Joseph cemeteries, is acquired south of the city.[183]

- 1861

- On February 12 Abraham Lincoln makes a stop in Indianapolis en route to Washington, D.C. to be sworn in as the sixteenth president of the United States.[184]

- The Indianapolis National Guards, City Grays, Independent Zouaves, Zouave Guards, and one additional group from Indianapolis are assigned to the Eleventh Regiment during the Civil War.[185]

- Camp Morton is set up as a mustering ground for Union troops on the state fairgrounds at Alabama Street. The camp's first soldiers arrive on April 17.[186]

- A local manufacturer begins production of ammunition near the Indiana Statehouse. The arsenal is relocated about one and a half miles (2.4 km) east of downtown Indianapolis.[187]

- Indianapolis Public Schools, the city's free public school system, reorganizes. Its elementary schools reopen in 1862; however, the city's public high school remains closed until 1864. In December 1867 the school board purchases the former Second Presbyterian Church building on the Circle and uses it as the city's public high school.[107][188]

- Hebrew Benevolent Society is organized.[189]

- Gilbert Van Camp founds Van Camp Packing Company, a canning business in the city. The company merges with Stokely Brothers and Company in 1933 to become Stokely-Van Camp, and establishes its corporate headquarters in Indianapolis. The company incorporates in 1994, but it no longer operates in the city.[190]

- 1862

- Camp Morton is converted to a prisoner-of-war camp for Confederate soldiers. The site returns to its original purpose as a fairgrounds after the war.[186]

- Congress passes legislation to establish a permanent federal arsenal at Indianapolis.[187] Approximately 76 acres (31 ha) of land are purchased east of town in 1863. Construction on the facility is completed in 1868.[174]

- The Indiana Sanitary Commission establishes its headquarters in Indianapolis.[191]

- Eighteen acres (7.3 ha) of land is purchased to establish Saint John Catholic Cemetery, two miles (3.2 km) south of the city. It is renamed Holy Cross Cemetery in 1891.[192]

- Young Men's Literary and Social Union is organized.[189]

- Indiana State Museum is established.[citation needed]

- Indianapolis and Madison Railroad is in operation.[citation needed]

- 1863

- The Battle of Pogue's Run, a political confrontation at the state's Democratic convention, occurs in May.[193]

- Kingan Brothers, renamed Kingan and Company in 1875, opens its first packing facility in Indianapolis.[194]

- The city's first central watch tower and alarm bell, an early fire warning system, is established.[195] The city's first electric fire alarm system is installed in 1868.[196]

- An Indianapolis Home for Friendless Women is initially built on seven acres (2.8 ha) of donated land south of the city; however, it is never completed. The home is reestablished closer to the city's center in 1867.[197]

- Crown Hill Cemetery is established.[44] The site is dedicated on June 1, 1864.[198]

- Indianapolis, Rochester and Chicago Railroad in operation.[citation needed]

- 1864

- Indianapolis Board of Trade is organized.[85]

- Indianapolis, Peru and Chicago Railway is in operation.[citation needed]

- Indianapolis High School, renamed Shortridge High School in 1897, opens in two rooms of a ward (elementary) school.[116][199]

- The Citizen's Street and Railway Company begins operating the city's first mule-drawn streetcar line from the Union railway depot in June.[200]

- Saint Peter's Catholic parish is established. Its first church opens in 1865. It is renamed Saint Patrick's parish in 1870 and construction begins on a new church that is completed in 1871. The parish maintains separate parochial schools for boys and girls.[201][202]

- Formation of the Twenty-Eighth Colored Infantry, which begins in Indianapolis and becomes known as the 28th Regiment U.S. Colored Troops, is mustered into the U.S. Army on March 31.[203]

- 1865

- April 30 – Lincoln funeral train arrives in Indianapolis.[204]

- The state legislature establishes the Criminal Circuit Court of Marion County in Indianapolis on December 20.[205]

- The German-language Taglicher Telegraph, a weekly newspaper, and the Spottsvigel, a Sunday edition of the Telegraph, begin publication. The Telegraph becomes the city's first daily German-language newspaper in 1866.[15][206][207][208]

- Indianapolis and Vincennes Railroad is in operation.[citation needed]

- Construction begins on a boys' school at Saint John the Evangelist Catholic Church. In 1867 the school opens under the direction of the Brothers of the Sacred Heart. It closes in 1929, and its building is demolished in 1979.[209]

- 1866

- Jeffersonville, Madison and Indianapolis Railroad in operation.

- Citizens Gaslight and Coke Company is established.[210]

- City Hospital is equipped and staffed to begin treatment of civilian patients.[159]

- The Allen African Methodist Episcopal Church congregation is organized and occupies its first church building.[211]

- Saint Paul's Episcopal Church parish is organized. Its first church building is dedicated in 1869.[89][212]

- The city's Second Christian Church, its first African American Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) congregation, is founded. It is renamed Light of the World Christian Church in 1982.[29]

- The first Union soldiers' bodies that had been buried elsewhere in the city during the Civil War are reinterred in a tract of land at Crown Hill Cemetery.[213]

- Indianapolis hosts the first national Grand Army of the Republic encampment in November.[214]

- 1867

- State Law Library is founded.[215]

- Indianapolis, Cincinnati and Lafayette Railway is in operation.[citation needed]

- Indianapolis and St. Louis Railroad in operation.[citation needed]

- The German Protestant Orphan Asylum is organized. A new orphanage is erected on the south bank of Pleasant Run in 1869.[216]

- Governor's Circle is renamed Circle Park.[217]

- 1868

- Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati and Indianapolis Railroad is in operation.[citation needed]

- Indianapolis, Crawfordsville and Danville Railroad is in operation.[citation needed]

- Indianapolis Library Association is formed.[215]

- The first Unitarian Society of Indianapolis is organized.[152]

- The city's Third Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) congregation is organized. Its first church is dedicated in 1870 and its second church in 1888. Its third church, at Seventeenth and Broadway streets, is completed in 1914.[218]

- 1869

- Indianapolis, Bloomington and Western Railway is in operation.[citation needed]

- John H. Holliday founds the Indianapolis News, an evening daily newspaper. Its first issue appears on December 7.[219][220][221]

- The city establishes its first sewage system.[222]

- The Waterworks Company of Indianapolis is incorporated.[128]

- Mayflower Congregational Church, the city's second Congregational church, is organized. Its church is dedicated in 1870. The congregation consolidates with Plymouth Congregational Church in 1908.[223]

- South Street Baptist Church is organized.[166]

- The Indiana Medical College is organized.[224]

- The city's first German Reform Church congregation is organized.[225]

- The Indianapolis Library Association, a private, subscription–based library, is formed on March 18. In 1872 the association offers to transfer its collection of more than 4,000 books to help create a free public library in the city.[226] A new main public library opens on April 9, 1873, and its first branch library opens in 1896.[227]

- 1870 – Indianapolis population: 48,244.[221]

- The city's first Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA) branch is organized.[228]

- A Lutheran cemetery is established south of the city on twenty-five acres (10 ha) of land.[225]

- The Society of Friends (Quakers) establishes the Indianapolis Asylum for Friendless Colored Children, the state's only orphanage for African American children.[229]

- Irvington, an eastside residential suburb, is platted. It is annexed to Indianapolis in 1902.[230][231]

- 1871

- Indianapolis YMCA builds a new facility on North Illinois Street; a new building was constructed at the same location in 1887.[85][221]

- The Water Works Company of Indianapolis, chartered in 1869 and acquired by Indianapolis Water Company in 1881, delivers the first water supplied from a central waterworks to city residents.[232]

- 1872

- Indianapolis, Delphi and Chicago Railroad in operation.[citation needed]

- A free public Library is established in the city. Its first library opens in the city's high school in 1873.[233] The library moves to larger quarters in 1875 and in 1880. A new main library opens in 1893. Its first four branches open in 1896. A new main library building is dedicated in 1917.[234][235]

- Woodruff Place, a new suburban development, is established on October 2. The community is annexed to Indianapolis in 1962.[236][237]

- Lyman S. Ayres acquires controlling interest in N.R. Smith and Ayres, the successor to the N.R. Smith and Company, Trade Palace. The dry goods store first appears as L. S. Ayres and Company in 1874. By 2006 the final stores in the Ayres department store chain are either sold, converted to Macy's stores, or closed.[238]

- 1873

- Indianapolis Sun newspaper begins publication.[15]

- Indianapolis, Cincinnati and Lafayette Railroad in operation.[citation needed]

- Saint Joseph, an Irish Catholic parish, is organized on the city's east side. In 1880 the parish builds a new church, while the Sisters of Providence establish its parochial school. A new school building is erected on the parish's property in 1881.[201][239]

- The Indiana Reformatory Institution for Women and Girls opens in the city. It is renamed the Indiana Woman's Prison in 1904, and is later named the Indiana Women's Prison.[240]

- 1875

- Indianapolis, Decatur and Springfield Railway in operation.[citation needed]

- The Church of the Sacred Heart, the city's second German Catholic parish, is established on the city's south side. The parish replaces its original church in 1885 and again in 1894.[241][242]

- The Indianapolis Woman's Club is founded.[243]

- 1876

- The Indianapolis Benevolent Society is founded. It is reorganized as the Charity Organization Society in 1879.[244][245]

- Colonel Eli Lilly establishes a pharmaceutical manufactory on Pearl Street that becomes Eli Lilly and Company.[246]

- The Flower Mission is organized; it is incorporated in 1892.[247]

- Citizens Gas Light and Coke Company begins operation, but its gasworks explodes in 1877.[248]

- The Chevro Bene Jacob Orthodox Hebrew congregation is founded. Its name is changed to Sharah Tefilla in 1882. The group merges with Knesses Israel and Ezras Achim congregations in 1962 to form the United Orthodox Hebrew Congregation.[249]

- 1877

- Robert Bruce Bagby elected as first African American to serve on the Indianapolis City Council.[250]

- Indianapolis and Sandusky Railroad in operation.[citation needed]

- Regal Manufacturing Company, formerly Emil Wulschner and Son, a music dealer, is in business.[251][252]

- Indianapolis's first telephone service begins operations.[253]

- The Union Railroad Transfer and Stock Yards Company opens. Its name is changed to the Indianapolis Belt Railroad and Stockyard Company in 1881. Renamed Indianapolis Stockyards Company, Inc., it moves to another site in the city in 1961.[254]

- Central Avenue Methodist Episcopal Church, a consolidation of Trinity and Massachusetts Avenue Methodist churches, is organized.[255]

- The Indianapolis Literary Club is founded.[256]

- 1878

- Indianapolis's Belt Railroad, established in 1873, is completed.[257]

- 1879

- Woman's Temperance Publishing Association is formed.

- Boston School of Elocution and Expression is established.[44]

- Indiana Bee Keepers' Association is formed.[44]

- Indianapolis and Danville Railroad in operation.[citation needed]

- Members of the city's German community establish the Independent Turnverein.[258] The group remodels the former Third Presbyterian Church into a meeting hall, which is dedicated in 1885. A new building is erected on an adjacent lot in 1897.[259]

- The Benjamin D. Bagby and Company begin publishing the Indianapolis Leader in August; it is discontinued in 1890.[257][260]

- The city's Charity Organization Society is formed with the merger of several Indianapolis charities.[261]

- 1880 – Indianapolis population: 75,056.[257]

- The English Opera House, a lavishly decorated theater on the Circle, opens on September 27.[116][167]

- Indianapolis and Evansville Railroad in operation.[citation needed]

- Indianapolis and Ohio State Line Railway in operation.[citation needed]

- Chicago and Indianapolis Air Line Railway in operation.[citation needed]

- Saint Bridget, an Irish Catholic parish, is organized and construction is completed on its church. The parish's parochial school is erected in 1881.[262][263]

- 1881

- Eli Lilly and Company is incorporated.[citation needed]

- Garfield Park is created.[citation needed]

- William R. Holloway establishes The Indianapolis Times, a morning daily newspaper. The first issue appears on July 15.[264]

- The Indianapolis Brush Electric Light and Power Company is the first to provide the city with electricity for lighting and power.[265] The city's first incandescent light is used in 1888. In 1892 the Indianapolis Light and Power Company is established with the merger of the Brush Electric Company and the Marmon-Perry Light Company.[266]

- The Daughters of Charity of the St. Vincent de Paul Society establish St. Vincent's Infirmary, later renamed St. Vincent Hospital.[267]

- The fifteenth national Grand Army of the Republic encampment is held in the city in June.[268]

- Saint Francis de Sales parish is established.[269]

- 1882

- May Wright Sewall and her husband, Theodore Lovell Sewell, establish the Girls' Classical School. The college preparatory school continues operations until 1907.[270]

- 1883

- The Art Association of Indianapolis is founded and holds its first art exhibit.[271][272]

- A Lutheran-affiliated home for orphaned children and aged adults, a predecessor to the Lutherwood Children's Home, is founded in the city.[273]

- Eliza A. Blaker establishes the Kindergarten Normal Training School. In 1905 it becomes the Teachers College of Indianapolis; in 1926 it becomes affiliated with Butler University.[274]

- 1884

- The city's German community establishes an industrial training program in the German-English School. The Indianapolis Public Schools establishes its vocational training program at Shortridge High School in 1888.[275]

- William Hayden English completes the first section of a grand hotel adjacent to the English Opera House. The hotel's second section is added in 1896.[276]

- Congregation Ohev Zedek organizes. The Hungarian Hebrew congregation purchases the Indianapolis Hebrew Congregation's temple on Market Street in 1899. The congregation merges with the Beth-El congregation in 1927; the Market Street temple is demolished in 1933.[277]

- 1885

- Chess Club and Hendricks Club is organized.[44]

- 1886

- Indianapolis City Market opens.[278]

- Saint Anthony Catholic parish is established; its first church is dedicated in 1891; construction of a new church is completed in 1904.[279]

- 1887

- Indianapolis and Wabash Railway in operation.[citation needed]

- Indianapolis Camera Club is organized.[280]

- Construction on a new Indianapolis Union Station begins.[85][278]

- 1888

- Consumers Gas Company begins operation.[281]

- The city's first Seventh-day Adventist Church congregation is organized. The congregation dedicates a new church erected at Central Avenue and East Twenty-Third Street in 1905. In 1962 the congregation moves to Rural Avenue and East 62nd streets, where the church becomes known as the Glendale Church.[282]

- The Indianapolis Propylaeum, a women's cultural organization, is incorporated on June 6. The group erects a meeting hall in 1889.[283][284]

- Construction is completed on a Renaissance Revival-style Indiana Statehouse to replace an earlier structure built at the same location.[285]

- Construction on the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument begins. Its installation is completed in 1902. The monument is dedicated on May 15, 1902.[286]

- The Sun begins publication on March 12. It is renamed the Indiana Daily Times in 1914.[287] It was renamed the Indianapolis Times in 1922.

- Indianapolis Freeman newspaper begins publication.

- Indianapolis, Decatur and Western Railway in operation.[citation needed]

- Columbia Club is organized. The Republican-oriented private membership club, incorporated in 1889, opens its new ten-story building on the Circle in 1925.[288]

- 1889

- Indiana School of Art is established on the northwest corner of the Circle and Market Street.[289] It closes in 1897, when the Art Association of Indianapolis begins plans to establish the John Herron Art Institute on Talbott Street.[290]

- A Salvation Army establishes a chapter in the city.[291]

- The city's first Church of Christ, Scientist group is organized. In 1897 it is formally established as the First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Indianapolis.[292]

- Knesses Israel, a Russian Orthodox Hebrew congregation organizes.[293]

- 1890 – Indianapolis population: 105,436[294]

- The Commercial Club of Indianapolis is organized. The club becomes the Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce in 1912.[295]

- The city's first electric-powered streetcar service begins on June 18.[296]

- Indianapolis Natural Gas Company is formed with the merger of the Indianapolis Gas Light and Coke Company and the Indianapolis Natural Gas Company.[297]

- Arthur C. Newby, Edward C. Fletcher, and Glenn G. Howe establish the Indianapolis Chain and Stamping Company, a bicycle chain manufacturer that becomes known as the Diamond Chain Company.[298]

- 1891

- 1892

- The Indiana State Fair relocates to a new site on Thirty-eighth Street.[300]

- Saints Peter and Paul Catholic parish is organized. In 1905 construction begins on its cathedral, which is dedicated in December 1906.[239][301]

- 1893

- Construction begins on the Das Deutsche Haus (The German House), the city's center for German culture.[302] The east wing is completed in 1894. The remainder is completed over the next four years.[259] The finished building is dedicated in 1898, and renamed the Athenæum during World War I.[303]

- The Southside Turnverein is established.[258] The group dedicates its new Prospect Street facility in 1901.[259]

- John H. Holliday founds the Union Trust Company. It merges with the Indiana National Bank in 1950.[304]

- 1894

- First basketball played in the city at the Illinois Street YMCA.[294]

- The Indiana Dental College opens.[305]

- The Church of the Assumption parish is established in west Indianapolis.[301]

- 1895

- Emmerich Manual Training High School opens as the state's first public vocational education high school.[294][306]

- The Art Association of Indianapolis receives a bequest from John Herron to build an art school and art museum in the city.[307]

- 1896

- George P. Stewart and William H. Porter establish the Indianapolis Recorder.[308]

- William H. Block founds a retail department store on Washington Street.[309] The business is incorporated in 1907. Construction begins on a new eight-story building in 1910.[310]

- A new Holy Cross Catholic parish is established on Indianapolis's east side, reviving the name of the city's first Catholic church.[311]

- 1897

- Indianapolis annexes Haughville, Stringtown, and West Indianapolis.[294]

- Chicago, Indianapolis and Louisville Railway in operation.[citation needed]

- 1898

- The Catholic Diocese of Vincennes is renamed the Catholic Diocese of Indianapolis.[217] It is elevated to the Archdiocese of Indianapolis in 1944.[312]

- Flanner Guild, an African American social services agency, is established. It is incorporated in 1903 and renamed Flanner House in 1912.[313]

- The Newby Oval, a local quarter-mile oval bicycling track is built.[314]

- 1899

- Indianapolis and Louisville Railway,[citation needed] Indianapolis Southern Railway,[citation needed] and Central Railroad of Indianapolis in operation.[citation needed]

20th century

[edit]1900s

[edit]- 1900

- Indianapolis population: 169,164.[315]

- The first interurban arrives in the city on January 1, from Columbus, Indiana.[316]

- 1901

- The first Church of the Brethren in Indianapolis holds it first services; it is formally organized in 1906. After several name changes, it becomes the Northview Church of the Brethren in 1955.[317]

- 1902

- October: St. Elmo Steak House in business.[318]

- Indiana Central University, later known as the University of Indianapolis, is chartered by the Church of the United Brethren in Christ.[319]

- John Herron Art Institute opens on Talbott Street.[320] Its new building, completed in 1906, also includes an art museum.[321] The building is remodeled in 1929, and the art school becomes part of Indiana University's campus at Indianapolis in 1967.[322]

- Indianapolis Indians baseball team active.[citation needed]

- Nordyke and Marmon, which becomes known as the Marmon Motor Car Company, begins manufacturing cars in Indianapolis.[319]

- 1903

- George F. McCullough begins publication of The Indianapolis Star newspaper on June 6.[319][323]

- A train wreck on October 31, known as the Purdue Wreck, kills sixteen people traveling to Indianapolis from Lafayette to attend a Purdue University football game.[324]

- Indiana University begins development of the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis.[319]

- The United Hebrew Congregation is organized.[325]

- The city's Second Church of Christ, Scientist, is founded.[326]

- All Souls Unitarian Church is organized.[151]

- The state's first juvenile court is established in the city.[327]

- 1904

- The Indianapolis Traction and Terminal Company, established in 1902, erects the Indianapolis Traction Terminal, the city's interurban terminal on West Market Street; it opens on September 12.[328]

- The U.S. Army establishes Fort Benjamin Harrison in Lawrence township, northeast of the city.[329]

- 1905

- U.S. District Courthouse, which also includes the city's main U.S. post office, is built on Ohio Street between 1903 and 1905. Additions are made between 1935 and 1938.[330]

- The United Brethren of Christ founds Indiana Central University, which opens on September 26. The school is named the University of Indianapolis in 1986.[331]

- The Jewish Federation of Indianapolis, later renamed the Jewish Federation of Greater Indianapolis, is established.[332]

- Anna Stover and Edith Surbey establish Christamore, a settlement house, in the city.[333]

- 1906

- Citizens Gas Company is incorporated. It is renamed Citizens Gas and Coke Utility in 1935.[281]

- Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church, the state's first Greek Orthodox church, is established. The congregation moves into a converted home in 1915, and relocates to a new church building in 1960.[334]

- Carl G. Fisher, James A. Allison, and P. C. Avery found Concentrated Acetylene Company, the predecessor to Presto-O-Lite. The company is sold to Union Carbide in 1917.[335]

- The Big Four Railroad, a subsidiary of the New York Central Railroad, purchases land to establish a railcar repair facility at Beech Grove.[336]

- American Motor Car Company in business.[citation needed]

- The city's Slovenian community establishes the Church of the Holy Trinity, a Catholic parish in Haughville. The parish church is dedicated in 1907.[337]

- Frank Flanner establishes Flanner House, a social services agency.[338]

- 1907

- Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral dedicated on December 21.[339]

- University Heights is incorporated. It is annexed by the city in 1923.[340]

- Earliest record of Industrial Workers of the World Industrial Union No. 96.[341]

- 1908

- Construction on the city's first Methodist Hospital building is completed.[342]

- 1909

- Local businessmen Carl Fisher, James A. Allison, Frank H. Wheeler, and Arthur Newby, purchase land west of Indianapolis to establish the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, which opens in September.[343]

- Parry Auto Company in business.[citation needed]

- The Cole Motor Car Company, established in 1909, builds high-quality automobiles at its Indianapolis factory to compete with Cadillac models from General Motors.[344]

- The city's Italian community establishes Holy Rosary Catholic parish.[345]

- Garfield Thomas Haywood founds Christ Temple Apostolic Faith Assembly. Its Pentecostal church is built on Fall Creek Parkway in 1924.[346]

- George Kessler, an urban planner and landscape architect, completes the Indianapolis park and boulevard plan.[339]

1910s

[edit]- 1910

- Indianapolis population: 233,560.[339]

- May: Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument is installed at Greenlawn Cemetery.[347]

- Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company relocates to Indianapolis.[339]

- Indiana University Medical Center is established.[339]

- Ezras Achim, an Orthodox Hebrew congregation, is founded on the city's south side. It merges with Knesses Israel and Sharah Tefilla congregations in 1962 to form the United Orthodox Hebrew Congregation and moves to a temple at Central Avenue and Kessler Boulevard.[348]

- 1911

- May 30: Ray Harroun wins the inaugural Indianapolis 500 motor race.[339]

- Ideal Motor Car Company in business.[citation needed]

- Episcopal Church of All Saints dedicated.[citation needed]

- 1912

- May 12-18: Indianapolis hosts the 1912 Convention of the Socialist Party of America.

- Arsenal Technical High School is established as a technical training school.[349]

- The Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce is established following the merger of the Commercial Club of Indianapolis with five other organizations.[295]

- 1913

- March 23-26: Great Flood of 1913 strikes several areas of the city.[350]

- October 31–November 7: Indianapolis streetcar strike of 1913.[349][351]

- The 17-story Barnes and Thornburg Building (originally Merchants National Bank Building) is completed; tallest building in the city until 1962.[352][353]

- James A. Allison establishes a machine shop, the forerunner to the Allison Engineering Company, and later named Allison Gas Turbine and Allison Transmission. General Motors acquires the company in 1929. In 1937 the company begins a $5 million expansion of its Indianapolis facility.[354]

- Congregation Sephard of Monastir is established. Its name is later changed to Etz Chaim Congregation.[355]

- Senate Avenue YMCA opens.[356]

- 1914

Downtown Indianapolis, c. 1914 - Robert W. Long Hospital is dedicated.[357]

- 1915

- June: Flag of Indianapolis's first design is adopted.[358]

- The state legislature establishes the Indiana Historical Commission.[359]

- Congregation Beth El is organized; its first synagogue is completed in 1925.[360]

- 1916

- August: Circle Theatre opens.[349][361]

- Holliday Park, established on the former estate of John H. Holliday and his wife, is deeded to the city. It becomes a part of the city park system in 1932.[362]

- 1917

- October 8: Indianapolis Public Library's Central Library opens.[363]

- Broad Ripple Park Carousel installed.[citation needed]

- 1918

- The city's first Assemblies of God congregation is established.[364]

- Pentecostal evangelist Maria Woodworth-Etter establishes the Woodworth-Etter Tabernacle, which is later renamed the Lakeview Christian Center.[365]

- Cathedral High School first opens in a Catholic grade school at 13th and Pennsylvania streets. Its new building at 14th and Meridian streets is completed in 1927. The high school relocates to the former Ladywood-St. Agnes campus on East 56th Street in 1976.[366]

- Elaborate Armistice Day celebrations are held in November.[367]

- Saint Rita parish, established to serve the city's African American Catholics, dedicates it first church. A new church built on Martindale Avenue is dedicated in 1959.[368]

- 1919

- The headquarters for the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World is moved from Portland, Oregon, to Indianapolis.[369]

- A Welcome Home parade in May celebrates the arrival of World War I veterans in the city.[367]

- July: Garfield Park riot of 1919[370]

1920s

[edit]- 1920

- Dusenburg Automobile and Motors Company is established. It is dissolved in 1937.[371]

- Indianapolis Athletic Club is founded.[372]

- September: Indianapolis hosts the 54th Grand Army of the Republic encampment.[372]

- Indiana Bell is organized to provide telephone service in the state.[373]

- 1921

- May 18: Taggart Baking Company (acquired by Continental Baking Company in 1925) debuts Wonder Bread.[374]

- December 31: Indianapolis's first radio station, 9ZJ (later WLK), goes on air.[375]

- Indianapolis hosts the 55th Grand Army of the Republic encampment.[372]

- Cadle Tabernacle, a site for large-scale religious gatherings, is built at Ohio and New Jersey streets.[376][377]

- 1922

- March 16: Lynching of George Tompkins[378]

- 1923

- Indianapolis Convention and Publicity Bureau, a forerunner to the Indianapolis Convention and Visitors Association (later known as Visit Indy), is established.[372]

- 1924

- Construction on the Indiana World War Memorial Plaza begins.[379]

- Riley Hospital for Children is completed.[376]

- 1925

- Mary Stewart Carey founds Children's Museum.[379]

- November 3: John L. Duvall is elected mayor.[380]

- 1927

- Crispus Attucks High School opens.[379]

- Indiana Theatre, Rivoli Theater, and Walker Building and Theatre open.

- Cox Field, the city's first airport is established. It is renamed Stout Army Air Field in 1929.[381]

- William H. Coleman Hospital for Women is completed.[357]

- Indianapolis Power and Light Company is established with the consolidation of the city's two remaining electric utilities.[281]

- Indiana World War Memorial Plaza cornerstone is laid on July 4, but construction is not completed until the 1930s.[382]

- Mormons dedicate their first Indianapolis chapel.[383]

- Congregation Beth El Zedeck is formed from the merger of Beth El and Ohev Zedeck Hebrew congregations. In 1958 the congregation moves to its new temple at Spring Mill Road and 56th Street.[384]

- The Jewish Welfare Fund is established. It merges with the Jewish Federation of Indianapolis to form the Jewish Welfare Federation of Indianapolis in 1948.[385]

- October 27: Mayor Duvall resigns following conviction on state corruption charges; Lemuel Ertus Slack is appointed to complete the remainder of Duvall's term on November 8.[380]

- October 31: Inaugural Historic Irvington Halloween Festival.[386]

- 1928

- Butler University relocates its campus from Irvington to Fairview Park, which it purchased in 1922 from the Indianapolis Street Railway Company.[387]

- Goodwill Industries opens a facility in the city.[388]

- 1929

- Scottish Rite Cathedral is completed.[389]

- Ferdinand Schaefer establishes the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra.[389]

- Jehovah's Witnesses build a Kingdom Hall at College Avenue and 27th Street; a second hall was established approximately ten years later.[390]

- Hinkle Fieldhouse, built on Butler University's Fairview Park campus, is completed.[391]

- May 25: Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument is rededicated in Garfield Park.[347]

- November 5: Reginald H. Sullivan is elected to first term as mayor.

1930s

[edit]- 1930

- Indianapolis population: 364,161.[389]

- The Art Deco-style Circle Tower, the city's first high-rise building to employ setbacks, is completed.[392]

- November 2: Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra performs its inaugural concert at Shortridge High School.[393]

- 1931

- Indianapolis Indians play first game in the new Perry Stadium.[389]

- September 25: Indianapolis Municipal Airport (forerunner to Indianapolis International Airport) is dedicated on the city's southwest side.[394]

- 1934

- Indiana State Library and Historical Bureau building is dedicated on December 7.[389]

- The Indianapolis Art Center (originally the Indianapolis Art League) is founded.[395]

- Nannette Dowd is first woman elected to Indianapolis Common Council.[396]

- 1936

- Construction begins on the city's Naval Reserve Armory. Completed in 1938, it is renamed Heslar Naval Armory in 1965.[397]

- The Sisters of Saint Francis acquire the James A. Allison estate and merge Saint Francis Normal School with Immaculate Conception Junior College to form Marian College. Classes begin classes on the Allison estate in 1937. It becomes the first Catholic co-educational college in Indiana in 1954.[398]

- 1937

- International Harvester builds a new engine plant. A foundry is added in 1939.[399]

- Lilly Endowment is established.[400]

- 1938

- Lockefield Gardens public housing project opens.[389]

- 1939

- Corteva Coliseum (originally Indiana State Fairgrounds Coliseum) opens.[citation needed]

1940s

[edit]- 1940

- 1943

- Geist Reservoir is completed.[402]

- 1945

- July 30: In the waning weeks of World War II, the 1,196-man crew of the USS Indianapolis heavy cruiser is torpedoed by an Imperial Japanese Navy submarine. Some 900 servicemen survive the initial attack; however, only 316 are rescued four days later. It is among the deadliest disasters in U.S. naval history.[403]

- November 14: Businessman Tony Hulman purchases the shuttered Indianapolis Motor Speedway.[404]

- 1947

- November 4: Al Feeney is elected mayor.

- 1949

- May 30: WFBM-TV, the city's first commercial television station, debuts.[405]

- August 31: Indianapolis hosts the final national Grand Army of the Republic encampment in August with six American Civil War veterans in attendance.[406]

1950s

[edit]- 1950

- Indianapolis population: 427,173

- 1951

- November 6: Alex Clark is elected mayor.

- 1953

- The city's First Southern Baptist Church is established.[407]

- 1954

- Jim Jones establishes the Peoples Temple in the city. Jones and 140 church members relocate to California in 1965.[408]

- 1955

- November 8: Philip Bayt is elected to a second (non-consecutive) term as mayor.

- November 15: An F2 tornado hits downtown Indianapolis, injuring two.[409]

- Morse Reservoir is built.[402]

- 1957

- Indiana Herald-Times which originated as the Hoosier Herald in 1949, begins publication.[15] The newspaper's name was shortened to the Indiana Herald in 1960.[410]

- 500 Festival is established.[386]

- 1958

- January 30: Tomlinson Hall is destroyed by fire.

- December 9: John Birch Society is founded.[411]

- 1959

- November 3: Charles Boswell is elected mayor.

1960s

[edit]- 1960

- December 20: Indiana Government Center North is completed.[412]

- Indianapolis population: 476,258.[413]

- 1962

- City-County Building is completed.[413]

- Indianapolis Airport Authority is established.[414]

- Woodruff Place is annexed by Indianapolis following a legal battle that was decided by the Indiana Supreme Court.[415]

- 1963

- May 20: Flag of Indianapolis's third design is adopted, replacing 1915 flag.[416]

- October 31: Propane gas explosion kills 81 and injures 400 during an ice show at the Indiana State Fairgrounds Coliseum.[417]

- November 5: John J. Barton is elected mayor.

- Slippery Noodle Inn in business.[418]

- 1964

- April 18: Indianapolis Zoo opens in Washington Park.[413]

- 1965

- October 11: Indianapolis Times newspaper ceases publication.[419]

- October 26: Murder of Sylvia Likens.[420]

- 1966

- Indianapolis Early Music established.[421]

- 1967

- January 31: Indiana State Museum opens in old Indianapolis City Hall.[422]

- November 7: Richard Lugar elected to first term as mayor.

- Indiana Pacers professional basketball team is formed.[423]

- 1968

- April 4: Robert F. Kennedy's speech on the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. is delivered in the city.[424]

- April 30: First enclosed shopping mall, Lafayette Square Mall, opens on the city's northwest side.[425]

- 1969

- Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) is established after the two universities merge operations of their Indianapolis campus extensions.[424]

- Indiana Medical History Museum established.[426]

- Governor Edgar Whitcomb signs Unigov Act to form a new administrative structure called Unigov to streamline operations of city and Marion County government;[424] however, there were many exceptions to the local government consolidation.[427]

- June 5–7: 1969 Indianapolis riots occur.

1970s

[edit]- 1970

- Indianapolis population: 744,624.[424][428]

- Indianapolis City–County Council is established.[429]

- The Art Association of Indianapolis opens a new art museum on the grounds of Oldfields, an estate donated by Josiah K. Lilly Jr.; it is later named the Indianapolis Museum of Art.[307]

- Indiana National Bank completes a 37-story modern office tower, the tallest building in the state at the time, at One Indiana Square.[430][424]

- Riverside Amusement Park closes.[431]

- 1971

- May 25–28: Indianapolis hosts international delegation for the NATO Conference on Cities.[432]

- August 18: Federal judge Samuel Hugh Dillin finds Indianapolis Public Schools guilty of de jure racial segregation.[433]

- November 2: Richard Lugar elected to second term as mayor.

- Indiana Black Expo begins.[424]

- 1972

- June 10: Eagle Creek Park opens.[434]

- September 13: Castleton Square shopping mall opens.

- College Life Insurance Company's Pyramids are completed on city's northwest side by famed architect Kevin Roche.

- Indiana Convention Center opens.

- Indiana Repertory Theatre is founded.[435]

- 1973

- City-County Council establishes the Indianapolis Public Transportation Corporation (Metro) and assumes the debts of Indianapolis Transit System Inc., a private company.[436]

- November 5: W. T. Grant fire.

- 1974

- April: Washington Square shopping mall opens.

- September 15: Market Square Arena opens.[437]

- 1975

- November 4: William Hudnut elected to first term as mayor.

- 1976

- Weir Cook Airport is renamed Indianapolis International Airport.[436]

- 1977

- February 8–10: Tony Kiritsis hostage situation.

- June 26: Elvis Presley performs final live concert at Market Square Arena.[438]

- Indianapolis Monthly lifestyle magazine is published.

- Martin University is founded by Boniface Hardin.

- 1978

- January: Indianapolis records its greatest monthly snowfall total (30.6 inches (780 mm)); Mayor Hudnut declares a three-day snow emergency during the Great Blizzard of 1978, the longest in the city's history.[439]

- Sister city relationship established with Taipei, Taiwan.[440]

- 1979

- White River State Park is established.[441]

- November 6: William Hudnut elected to second term as mayor.

1980s

[edit]- 1980

- Indianapolis population: 700,807

- Gleaners Food Bank is established.

- Indianapolis Business Journal is founded.

- Baptist Bible College of Indiana is founded in the city.[442]

- 1981

- Indianapolis Public Schools begins court-ordered desegregation busing in Marion County.[433]

- 1982

- July: City hosts the National Sports Festival.

- July: Major Taylor Velodrome opens.[443]

- International Violin Competition of Indianapolis debuts.

- Carroll Track & Soccer Stadium opens on the IUPUI campus.

- American United Life Insurance Company completes 38-story AUL Tower; it becomes the tallest building in the state at the time.[444]

- 1983

- March 7: The Bob and Tom Show debuts on Indianapolis radio station WFBQ.

- November 8: William Hudnut elected to third term as mayor.

- Phoenix Theatre is founded.

- CP Morgan is founded.

- 1984

- March 29: Baltimore Colts professional football franchise relocates to Indianapolis and becomes the Indianapolis Colts.[445]

- May 26: Indianapolis hosts the 1984 Summer Olympics torch relay during the 500 Festival Parade.[446]

- August 5: Hoosier Dome opens.[445]

- Circle City Classic debuts.[386]

- 1985

- June 12: Community Hospital North opens on the city's north side near Castleton.[447]

- 1986

- Indianapolis Union Station reopens after extensive renovation into festival marketplace.[448]

- 1987

- April: The Damien Center is founded to provide health and counseling services to people with HIV/AIDS.

- August 7–23: City hosts tenth Pan American Games.[445]

- October 20: A plane crash near Indianapolis International Airport kills ten people.[449]

- November 3: William Hudnut elected to fourth term as mayor.

- Kuntz Memorial Soccer Stadium opens.

- 1988

- June 11: Indianapolis Zoo opens its new facility at White River State Park.[450]

- Sister city relationship established with Cologne, Germany.[440]

- 1989

1990s

[edit]- 1990

- Indianapolis population: 741,952.[451]

- March 14: NUVO alternative weekly is founded.[452]

- April 8–11: Ryan White dies of complications from AIDS at Riley Hospital for Children.[453] More than 1,500 attend White's funeral service at Second Presbyterian Church which is broadcast to an international audience.[454]

- Bank One, Indianapolis, completes 51-story skyscraper, the state's tallest building; later renamed Salesforce Tower.[451]

- 1991

- November 5: Stephen Goldsmith elected to first term as mayor.

- Heartland International Film Festival debuts.[386]

- 1992

- January: L. S. Ayres closes its flagship department store at the corner of Meridian and Washington streets downtown.[455]

- September 11: A mid-air collision between two private planes 10 miles (16 km) south of downtown results in six fatalities, including the two pilots and prominent civic leaders Robert V. Welch, Frank McKinney, John Weliever, and Michael Carroll.[456]

- 1993

- 1994

- January 19: Indianapolis reaches a record low temperature of −27 °F (−33 °C) during the 1994 North American cold wave.[457]

- August 6: Indianapolis Motor Speedway hosts 250,000 spectators for NASCAR's inaugural Brickyard 400. As of February 2021[update], the event remains NASCAR's highest-attended race.[458]

- 1995

- August 2: USS Indianapolis National Memorial is dedicated.

- September 8: Circle Centre Mall opens.

- November 7: Stephen Goldsmith elected to second term as mayor.

- Franciscan Health Indianapolis opens new hospital on the city's south side in Franklin Township.[459]

- Indianapolis Artsgarden opens.

- Indy Pride is established.

- 1996

- June 4–5: Indianapolis hosts the 1996 Summer Olympics torch relay.[460]

- July 11: Victory Field opens at White River State Park.

- Indianapolis Firefighters Museum opens.[116]

- Sister city relationship established with Scarborough, Canada.[461][462]

- City website online (approximate date).[463][chronology citation needed]

- 1998

- May 1: Crispus Attucks Museum is established.

- Sister city relationship with Scarborough, Canada dissolved due to 1998 amalgamation of Toronto.[462]

- 1999

- May 28: Medal of Honor Memorial is dedicated.

- June 7: Women's National Basketball Association awards Indianapolis an expansion franchise; the Indiana Fever women's professional basketball team debuts on June 1, 2000.[464]

- June: White River Gardens opens at the Indianapolis Zoo.

- July 26: National Collegiate Athletic Association relocates its headquarters to Indianapolis from Kansas City, Missouri.[465]

- October 1: Indianapolis News evening newspaper ceases publication.

- November 2: Bart Peterson elected to first term as mayor.

- November 6: Gainbridge Fieldhouse (originally Conseco Fieldhouse) opens.[466]

- Indy Jazz Fest debuts.[386]

21st century

[edit]2000s

[edit]- 2000

- Indianapolis population: 781,926

- March: NCAA Hall of Champions opens.[465]

- September 24: Indianapolis Motor Speedway hosts its first United States Grand Prix; the track hosted the Formula One race annually between 2000 and 2007.[467]

- October 29: Indiana AIDS Memorial is dedicated at Crown Hill Cemetery as the first permanent memorial to AIDS victims in the Midwest.[468]

- November 28: City of Indianapolis v. Edmond is decided by the U.S. Supreme Court.

- 2001

- June 6: Indiana Law Enforcement and Firefighters Memorial is dedicated.[469]

- July 8: Market Square Arena is imploded.[470]

- Harrison Center (originally Harrison Center for the Arts) is founded.[471]

- Sister city relationship established with Piran, Slovenia.[440]

- 2002

- January 7–8: Indianapolis hosts the 2002 Winter Olympics torch relay.[472]

- May 22: Indiana State Museum relocates to modern facility at White River State Park.[473]

- September 20: National Weather Service issues a rare tornado emergency for Marion County. An F3 tornado results in 130 injuries and US$156 million in property damage, but zero fatalities.[474]

- Consulate of Mexico opens in Indianapolis.[475]

- 2003

- June 28: Indiana University Health People Mover begins service.

- September 1: City records highest single-day rainfall total (7.2 inches (180 mm)) after remnants of Tropical Storm Grace stall over central Indiana.[457]

- November 4: Bart Peterson elected to second term as mayor.

- First five Indianapolis Cultural Districts are designated: Broad Ripple Village, Canal and White River State Park, Fountain Square, Mass Ave, and the Wholesale District.[476]

- 2004

- Indy Film Fest (originally the Indianapolis International Film Festival) debuts.[386]

- Final phase of the Monon Trail, the city’s first rail trail, is completed.[477]

- 2005

- Inaugural Indianapolis Theatre Fringe Festival.[386]

- 2006

- February 5: Hindu Temple of Central Indiana opens.[478]

- March 27: Conrad Indianapolis opens; tallest building completed in city during the 2000s.

- June 1: Hamilton Avenue murders.

- 2007

- January 1: Indianapolis Police Department and Marion County Sheriff's Department law enforcement division consolidate, establishing the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department (IMPD).[479]

- February 4: Indianapolis Colts defeat the Chicago Bears 29–17 in Super Bowl XLI.[480]

- November 6: Greg Ballard elected to first term as mayor.[481]

- December 9: Central Library reopens after extensive renovation and expansion.[482]

- Construction begins on the Indianapolis Cultural Trail.[479]

- Central Indiana Regional Transportation Authority is established.[483]

- 2008

- April 28: U.S. Supreme Court upholds the constitutionality of Indiana’s voter identification law in Crawford v. Marion County Election Board. Bill Crawford, state representative for Indianapolis (1972–2012), served as plaintiff.[484]

- August 16: Lucas Oil Stadium opens.[485]

- November 12: Indianapolis International Airport debuts $1.1 billion midfield terminal, completing largest building project in city history.[486]

- December 20: RCA Dome (originally the Hoosier Dome) is imploded.

- Sister city relationship established with Hangzhou, China.

- Inaugural Indianapolis Monumental Marathon is held.

- 2009

- Sister city relationships established with Campinas, Brazil, and Northamptonshire, United Kingdom.[440]

2010s

[edit]- 2010

- Indianapolis population: 829,718

- June 20: Virginia B. Fairbanks Art & Nature Park: 100 Acres opens.[487]

- Sister city relationship established with Hyderabad, India.[440]

- 2011

- January: Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library opens.[488]

- February 4: JW Marriott Indianapolis opens;[489] tallest building completed in city during the 2010s.

- April: Indianapolis sells its water and wastewater utilities to Citizens Energy Group, a public charitable trust.[490]

- August 13: Indiana State Fair stage collapse kills seven and injures 58 spectators.[491]

- September 11: Indiana 9/11 Memorial is dedicated.[492]

- November 8: Greg Ballard elected to second term as mayor.[493]

- November 8: Zach Adamson elected to first term as first openly gay member of Indianapolis City-County Council.[494]

- 2012

- February 5: Lucas Oil Stadium hosts Super Bowl XLVI.

- October 21: Indiana Fever defeat the Minnesota Lynx 3–1 to earn their first WNBA title.

- November 10: Richmond Hill explosion kills two, injures seven, and damages or destroys some 80 homes.[495]

- 2013

- January 26: Indy Eleven professional soccer team established.[496]

- May 10: Indianapolis Cultural Trail is completed.[497]

- August 12: Marian University opens the Tom and Julie Wood College of Osteopathic Medicine.

- November 11: Indy Fuel minor league ice hockey team established.[498]

- December 6: Sidney & Lois Eskenazi Hospital opens, replacing Wishard Memorial Hospital.[499]

- 2014

- April 22: Indiana Pacers Bikeshare launched as the city's first public bicycle-sharing system.[500]

- 2015

- November 3: Joe Hogsett elected to first term as mayor.[501]

- 2016

- February 10: United Technologies announces plans to offshore its Indianapolis Carrier manufacturing operations to Monterrey, Mexico.[502]

- May 29: 100th running of the Indianapolis 500 draws an estimated 350,000 spectators to Indianapolis Motor Speedway.[503]

- June 26: IndyGo's Julia M. Carson Transit Center opens.[504]

- September 12: The Indianapolis Star breaks the USA Gymnastics sex abuse scandal.[505]

- Indianapolis Public Schools's desegregation busing mandate expires; between 1981 and 2016, some 19,000 African American students were bused from IPS to neighboring township school districts.[433]

- 2017

- 2019

- February 6: Indiana University Health People Mover ends service.[507]

- March 20: NeuroDiagnostic Institute opens, replacing Larue D. Carter Memorial Hospital.[508]

- September 1: IndyGo's Red Line opens as the city's first bus rapid transit service.[509]

- November 5: Joe Hogsett elected to second term as mayor.[510]

2020s

[edit]- Sometime between 2020 and 2023, Marion County's population becomes majority non-white.[511]

- 2020

- Indianapolis population: 887,642[512]

- January 6: Roger Penske acquires Indianapolis Motor Speedway and IndyCar Series from Hulman & Company.[513][514]

- March 6: Indianapolis resident is Indiana's first confirmed COVID-19 case.[515] Stay-at-home restrictions are issued on March 23 by state and local officials in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Indiana.[516]

- May 29: George Floyd protests begin in the city.

- June: Celebrations begin in commemoration of the city's bicentennial.[517]

- June 8: Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument is dismantled.[347]

- August: Black Lives Matter street mural is installed on Indiana Avenue.

- 2021

- March–April: Indianapolis hosts entire 2021 NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament.[518]

- April 15: A mass shooting at a FedEx facility on the city's southwest side kills nine and injures seven.[519][520]

- 2022

- May 16: Community Justice Campus opens, site of Marion County Sheriff's Office, new courthouse, jail, and other facilities.[521]

- 2023

- January: Sister city relationship established with Querétaro, Mexico.[522]

- July 14: City adopts General Ordinance 34, a trigger law that would enact various local gun control measures if Indiana's state preemption law is repealed or struck down.[523]

- November 7: Joe Hogsett elected to third term as mayor.[524]

- 2024

- April 8: Indianapolis experiences total solar eclipse.[525]

- July 1: IUPUI is dissolved, creating the separate institutions of Indiana University Indianapolis and Purdue University in Indianapolis.[526]

- July 17–21: Indianapolis hosts the U.S. Catholic Church's 10th National Eucharistic Congress.[527]

- October 13: IndyGo's Purple Line begins service.[528]

Images

[edit]-

Advertisements, 1862

-

Indiana State Fair, Indianapolis, 1874

-

G.A.R. Review, 1893

-

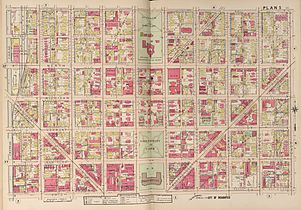

Map of part of Indianapolis, 1908

-

Map of part of Indianapolis, 1916

See also

[edit]- History of Indianapolis

- List of mayors of Indianapolis

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Center Township, Marion County, Indiana

Notes

[edit]- ^ A. C. Howard (1857). A. C. Howard's Directory for the City of Indianapolis: Containing a Correct List of Citizens' Names, Their Residence and Place of Business, with a Historical Sketch of Indianapolis from its Earliest History to the Present Day. Indianapolis: A. C. Howard. p. 3.

- ^ Howard, p. 2.

- ^ M. Teresa Baer (2012). Indianapolis: A City of Immigrants (PDF). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-87195-299-8.

- ^ Howard, p. 1.

- ^ Howard, p. 4.

- ^ Jacob Piatt Dunn (1910). Greater Indianapolis: The History, the Industries, the Institutions, and the People of a City of Homes. Vol. I. Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Company. p. 26.

- ^ William A. Browne Jr. (Summer 2013). "The Ralston Plan: Naming the Streets of Indianapolis". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. 25 (3). Indianapolis, Ind.: Indiana Historical Society: 8.

- ^ Ignatius Brown (1868). Logan's History of Indianapolis from 1818. Indianapolis: Logan and Company. p. 4.

- ^ Berry R. Sulgrove (1884). History of Indianapolis and Marion County Indiana. Philadelphia: L. H. Everts and Company. p. 30.

- ^ Dunn, Greater Indianapolis, p. 31–32.

- ^ Dunn, Greater Indianapolis, p. 90–91.