This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

Voivode Todor Aleksandrov | |

|---|---|

A portrait of Aleksandrov with an autograph and dedication to Yavorov (Sofia, 1912). | |

| Native name | Тодор Александров Попорушев |

| Birth name | Todor Alexandrov Poporushev |

| Born | 4 March 1881 Novo Selo, Kosovo Vilayet, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 31 August 1924 (aged 43) Sugarevo, Tsardom of Bulgaria |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Unit | Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps |

| Battles / wars | |

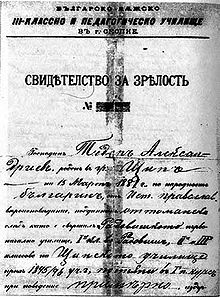

| Alma mater | Bulgarian Pedagogical School of Skopje Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki |

| Spouse(s) | Vangelia Aleksandrova |

| Children | Alexander Aleksandrov Maria Aleksandrova |

Todor Aleksandrov Poporushov, best known as Todor Alexandrov (Bulgarian/Macedonian: Тодор Александров), also spelt as Alexandroff (4 March 1881 – 31 August 1924), was a Macedonian Bulgarian[1][2][3] revolutionary, Bulgarian army officer, politician and teacher. He favored initially the annexation of Macedonia to Bulgaria,[4][5][6] but later switched to the idea of an Independent Macedonia as a second Bulgarian state on the Balkans.[7][8][9] Alexandrov was a member of the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organisation (IMARO) and later of the Central Committee of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation (IMRO).[10][11][12]

In North Macedonia, Aleksandrov, who was previously dismissed by the post-WWII Yugoslav Macedonian historiography as a controversial Bulgarophile and national traitor,[13] was added to the country's historical heritage as an ethnic Macedonian.[14] Though, this has caused political and public controversies.[15]

Life

[edit]Aleksandrov was born in Novo Selo, Kosovo vilayet, the Ottoman Empire (present-day suburb of Štip, North Macedonia) to Aleksandar Poporushev and Marija Aleksandrova. In 1898, he finished the Bulgarian Pedagogical School in Skopje and became a Bulgarian teacher consecutively in the towns of Kočani, Kratovo, the village of Vinica, and Štip. He attended the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki.

In 1903, Aleksandrov distinguished himself as an extraordinary leader and organizer of the Kočani Revolutionary District. He was arrested by the Ottoman authorities on 3 March 1903 and sent to Skopje under enforced police escort during the same night. He was sentenced to five years of solitary confinement by the extraordinary court there. In April 1904, he was released after an amnesty. Soon afterwards, he was appointed a head teacher in the Second high-school in Štip. Aleksandrov, in co-operation with Todor Lazarov and Mishe Razvigorov, worked day and night to organize the Štip Revolutionary District. The results of his activities were detected by the Ottoman authorities and in November 1904 he was forbidden to teach. On 10 January 1905, Aleksandrov's house was surrounded by numerous troops but he succeeded in breaking through the military cordoned and immediately joined the cheta (band) of Mishe Razvigorov where he became its secretary. Aleksandrov attended the First Congress of the Skopje Revolutionary Region as a delegate from the Štip district.[citation needed]

His deteriorating health led him to become a teacher in Bulgaria — the Black Sea town of Burgas in 1906, but after learning about the death of Mishe Razvigorov, he abandoned his work as a teacher and returned to Macedonia at once. In November 1907, Aleksandrov was elected as a district vojvoda (commander) by the Third Congress of the Skopje Revolutionary District.[citation needed]

On 2 August 1909, the Ottomans made another attempt to arrest him but failed again. In the spring of 1910, he and his cheta traversed the Skopje region and organized the revolutionary activities. In early 1911, Aleksandrov became a member of the Central Committee of the IMARO. In 1912, he became a vojvoda in the Kilkis and Thessaloniki districts where he carried out a number of sabotages against Ottoman targets, facilitating this way the Bulgarian cause in the First Balkan War. He supported the Bulgarian Army.[citation needed]

In 1913, he was at the headquarters of the Third Brigade of the Macedonian Militia in the Bulgarian army. After 1913 he organized the IMARO resistance against other nationalities, such as Serbs and Greeks. With the inclusion of Bulgaria in the First World War in October 1915, Todor Alexandrov was mobilized. At that time, the structures of the Military Defense Forces completely merged into the structure of the Bulgarian army. Aleksandrov himself made considerable efforts to organize the administration in the territories occupied by Sabia. On 4 November 1919, Aleksandrov was arrested by the government of Aleksandar Stamboliyski but he succeeded in escaping nine days later. In the spring of 1920, Aleksandrov went with a cheta (band) to Vardar Macedonia where he restored the revolutionary organization and attracted the world's attention to the unsolved Macedonian question. At the end of 1922, there was a bounty of 250,000 dinars placed on him by the Serbian authorities in Belgrade.[citation needed]

In 1924 IMRO entered negotiations with the Comintern about collaboration between the communists and the creation of a united Macedonian movement. The idea for a new unified organization was supported by the Soviet Union, which saw a chance to use this well-developed revolutionary movement to spread revolution in the Balkans and destabilize the Balkan monarchies. Alexandrov defended IMRO's independence and refused to concede on practically all points requested by the Communists. No agreement was reached besides a paper "Manifesto" (the so-called May Manifesto of 6 May 1924), in which the objectives of the unified Macedonian liberation movement were presented: independence and unification of partitioned Macedonia, fighting all the neighbouring Balkan monarchies, forming a Balkan Communist Federation and cooperation with the Soviet Union.[citation needed]

Failing to secure Alexandrov's cooperation, the Comintern decided to discredit him and published the contents of the Manifesto on 28 July 1924 in the "Balkan Federation" newspaper. Todor Aleksandrov and Aleksandar Protogerov promptly denied through the Bulgarian press that they have ever signed any agreements, claiming that the May Manifesto was a communist forgery. Shortly after, Alexandrov was assassinated in unclear circumstances, when a member in his cheta shot him on 31 August 1924 in the Pirin Mountains. He had a wife called Vangelia and two children (Alexander and Maria; a strong proponent of her father's ideals and IMRO's charter).[16]

View about the Macedonian Question

[edit]

IMRO and Alexandrov himself aimed at an autonomous Macedonia, with its capital at Salonika and prevailing Macedonian Bulgarian element. He took into consideration the decomposition of Greece and the incorporation into the autonomous Macedonia of the Macedonian territory which was under the Greek dominion. The part of Macedonia which was in Bulgaria was also foreseen to be incorporated into the autonomous Macedonia.[citation needed]

Legacy

[edit]The Macedonian historiography in the Yugoslav era regarded Aleksandrov as part of a group of "bulgarianized renegades of the Macedonian revolutionary and liberation movement".[19] After the independence of present-day North Macedonia, efforts were made by Macedonian politicians and historians to rehabilitate Aleksandrov.[20] Most Macedonian historians have regarded him as "the biggest traitor to the Macedonian cause" due to his pro-Bulgarian views for a long time, while other historians have called him out for his alleged involvement in many assassinations of other VMRO members and other political and military figures of the time. On the other hand, other historians have referred to him as "the soul and the brain of the Macedonian resistance" and as "Macedonia’s Robin Hood", attributing to him remarkable organizational skills and will.[13]

A local association of Bulgarians raised a monument of the revolutionary on 2 February 2008 in the city of Veles.[21][22] After the local administration refused to provide a place for the bust, it was raised in the yard of a local Bulgarian resident.[23] In the following night the resident received a number of threats and the monument was twice thrown down by unknown individuals.[24] Soon after, the monument was removed at the insistence of local authorities, as an unlawful construction. This incident caused Bulgarian president Georgi Parvanov to call upon the Macedonian government to review the history of Alexandrov's deeds on his meeting with Branko Crvenkovski in the town of Sandanski.[25]

In June 2012, a new statue called “Macedonian Equestrian Revolutionary” was erected in Skopje. As a consequence, an outcry among older residents erupted almost immediately when they noted the anonymous rider’s similarity to the historical figure.[26] Earlier the same month the opposition Social Democrats took to the streets to protest the changing of hundreds of street names, including a bridge that was to be named after Aleksandrov.[27] In October, a few months after the setting of the monument, on it appeared a board with the name of Todor Aleksandrov.[28]

In March 2021, the new Skopje municipal council majority by the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia decided to rename the names of many local sites. Thus, the bridge named after Alexandrov and the street named after the organization he led - IMRO, were renamed.[29] The former Skopje Mayor from VMRO-DPMNE Koce Trajanovski reacted that his successor Petre Šilegov has deleted part from the Macedonian history at the request of Bulgaria.[30]

A monument of Aleksandrov was erected in his birthplace of Novo Selo, Štip, in August 2024.[31]

Aleksandrov Peak on Graham Land, Antarctica, is named after Todor Aleksandrov.

Memorials

[edit]-

Monument of Alexandrov in Kyustendil, Bulgaria.

-

Monument of Alexandrov in Burgas, Bulgaria.

-

Monument of Alexandrov in Veles, Macedonia, demounted in 2008.

-

Bust of Todor Aleksandrov in Sofia, Bulgaria.

See also

[edit]References and notes

[edit]- ^ "Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) | History, Leaders, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-09-09.

- ^ Ivo Banac (2015). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. pp. 321–322. ISBN 9781501701931.

- ^ Rumen Daskalov; Tchavdar Marinov, eds. (2013). Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. Brill. pp. 308, 485. ISBN 9789004250765.

- ^ Wojciech Roszkowski, Jan Kofman (2016) Biographical Dictionary of Central and Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century. Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9781317475941, p. 883.

- ^ Dmitar Tasić (2020) Paramilitarism in the Balkans Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and Albania, 1917-1924, OUP Oxford, ISBN 9780191899218, p. 165.

- ^ Robert Gerwarth, John Horne, War in Peace. Paramilitary Violence in Europe After the Great War. (2013) OUP Oxford, ISBN 9780199686056, p. 150.

- ^ J. Pettifer as ed., The New Macedonian Question, St Antony's Series, Springer, 1999, ISBN 0230535798, p 68.

- ^ Marina Cattaruzza, Stefan Dyroff, Dieter Langewiesche as ed., Territorial Revisionism and the Allies of Germany in the Second World War: Goals, Expectations, Berghahn Books, 2012, ISBN 085745739X, p. 166.

- ^ Spyros Sfetas, The Birth of ‘Macedonianism’ in the Interwar Period p. 287. in the History of Macedonia, ed. Ioannis Koliopoulos, Museum of the Macedonian struggle, Thessaloniki, 2010; pp. 286-303.

- ^ Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question by Victor Roudometof, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002; ISBN 0275976483, pg. 99.

- ^ Crown of Thorns: The Reign of King Boris III of Bulgaria, 1918–1943 by Stephane Groueff, Rowman & Littlefield, 1998, ISBN 1568331142,p. 118.

- ^ Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900–1996 (by Chris Kostov), Peter Lang, 2010; ISBN 3034301960, pg. 78.

- ^ a b "Nameless Statue Causes Stir in Macedonia". Balkan Insight (BIRN). 28 June 2012.

- ^ Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, p. 140.

- ^ In 2021, the name of the Todor Alexandrov Bridge in Skopje, which was given to it in 2012 and provoked protests then, was changed back again. For more see: Зоре Нацева, Град Скопје ги врaќа старите имиња на Ленинова, Железничка, Мексичка, 4 Јули и други. Инфомах, March 25, 2021.

- ^ Македоно-одринското опълчение 1912-1913 г. : Личен състав по документи на Дирекция „Централен военен архив“. София, Главно управление на архивите, Дирекция „Централен военен архив“ В. Търново, Архивни справочници № 9, 2006. ISBN 954-9800-52-0. с. 16.

- ^ "Тодор Александров от Ново село, Щип, Вардарска Македония - "Писмо до Владимир Карамфилов от 6 юли 1919 г.", публикувано в "Сè за Македонија: Документи: 1919-1924", Скопје, 2005 година". Онлайн Библиотека Струмски. Retrieved 2022-09-19.

- ^ "ИСТИНАТА ЗА АВТОНОМИЯТА НА МАКЕДОНИЯ ВЪВ ВИЖДАНИЯТА НА ВМОРО И НА ТОДОР АЛЕКСАНДРОВ". www.sitebulgarizaedno.com. Retrieved 2022-09-19.

- ^ Boeckh, Katrin; Rutar, Sabine, eds. (2017). The Balkan Wars from Contemporary Perception to Historic Memory. Springer International Publishing. p. 301. ISBN 9783319446424.

- ^ Cvete Koneska (2016). After Ethnic Conflict: Policy-making in Post-conflict Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia. Taylor & Francis. p. 67. ISBN 9781317183976.

- ^ Sociétés politiques comparées 25 May 2010; Tchavdar Marinov, Université de Sofia ‘St. Kliment Ohridski’; New Bulgarian University - Historiographical revisionism and rearticulation of memory in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, p.3, note #5. Archived 15 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Nameless Statue Causes Stir in Macedonia", BalkanInsight.com, 28 June 2012.

- ^ Paul Reef, Macedonian Monument Culture Beyond ‘Skopje 2014’. From the journal Comparative Southeast European Studies https://doi.org/10.1515/soeu-2018-0037

- ^ "News.bg — ВМРО откри паметник на Тодор Александров в Македония". news.ibox.bg. 2 March 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ "News.bg — Македония и България са с обща история, обяви Първанов". news.ibox.bg. 5 March 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ Нова статуа ги разбуди старите расправии во Македонија. BIRN, July 13, 2012.

- ^ Martin Laine, Hero or villain? "New Skopje statue sparks controversy", Digital Journal, 29 June 2012.

- ^ Утрински вестик, „Војводата на коњ“ и официјално Тодор Александров. Archived 2012-10-22 at the Wayback Machine, 18 October 2012.(in Macedonian)

- ^ Советот на град Скопје ја усвои одлуката за промена на имињата на улиците, опозицијата најавува судска разврска. „Мета.мк“, 31 март 2021.

- ^ Коце Трајановски: Шилегов го брише Тодор Александров на барање на Бугарија. Mar 26, 2021, Faktor.mk.

- ^ "Тодор Александров доби споменик во родното штипско Ново Село, на 100 годишнината од неговата смрт". Telma. 31 August 2024.