A Ukrainian fairy tale, "Kazka" (Ukrainian: казка, pronounced [ˈkazkɐ] ⓘ), is a fairy tale from Ukraine. The plural of казка is казки (kazky). In times of oral tradition, they were used to transmit knowledge and history.[1]

Description

[edit]Ukrainian folk literature is vast.[2][3] Many Ukrainian fairy tales feature forests and grassy plains, with people working as farmers or hunters.[1] Many Ukrainian fairy tales feature animals.[4] There are often parallels with other regional traditions such as Russia, Turkey, and Poland.[5] One purpose of Ukrainian fairy tales was to teach children about dangers, and also the importance of growing crops for survival the following year.[1][4] Though teaching children was an important purpose of Ukrainian fairy tales, Ukrainian fairy tales were not exclusively for children.[6][7]

Characters in Ukrainian fairy tales often feature warriors, princes, and peasants.[5] Common features of narrative transition in Ukrainian kazky include mediators (objects, actions, notions, events, or conditions), magic helpers (objects, things, or supernatural beings, as in Mare's Head), and triggers (signs or prohibitions).[6] These elements perform a linking function in the narrative and provide motivation for the main character to move from one setting to another.[6]

Collection of fairy tales while under occupation

[edit]Professor of Folklore at the University of Alberta, Natalie Kononenko writes that while historically often under occupation of foreign powers, folklore was one of the few means of cultural expression allowed to Ukrainian authors and scholars.[8]

Russian Empire and Austria-Hungary

[edit]When eastern Ukraine was under the rule of the Russian Empire, activities thought to promote feelings of Ukrainian nationalism or pride were banned, but folklore, seen as the province of a rural, ignorant people, was thought to be harmless.[8] Because folklore was considered to advance a perception that Ukraine (called “Little Russia” by the Russian Empire) was a backward, border place, research and study of Ukrainian folklore was even considered beneficial for the subjugation of Ukrainians.[8] It is in part due to this permissive view on Ukrainian folklore that scholarly work on Ukrainian folklore from the 1800s is available today.[8]

Under the hierarchy of the Russian Empire, Russia considered itself “Great Russia”, Belarus “White Russia”, and Ukraine to be “Little Russia”.[8] As a result of this enforced hierarchy under the Russian Empire, much Ukrainian folklore was not initially published as Ukrainian folklore, but instead labeled as Russian folklore.[8] Thus, some folklore labeled as Russian folklore was subsumed Ukrainian folklore along with folklore from Belarus.[4] When Ukrainian folklore has been labeled as Russian, Ukrainian folk tales can be discerned from Russian folklore from the language used, and often with indications of a place where the folk tale was collected.[4] While a similar situation existed in western Ukraine under control of Austro-Hungary, there was less attempt to assimilate Ukrainian people and culture into a larger dominant political group.[8][9]

Soviet Union

[edit]Under Soviet Union rule encompassing both east and west Ukraine, folklore was treated more suspiciously by authorities.[9] The Soviet government realized the effectiveness of folklore and sought to replace traditional folklore with new Soviet folklore that promoted principles the Soviet government considered desirable such as submissiveness and collectivism.[9][10] Thus, Soviet rule censored older Ukrainian folklore and tales of aspects deemed threatening such as references to religion, or ideas which might encourage thoughts of Ukrainian pride or nationalism, including references particularly Ukrainian such as pysanky.[9]

Ukrainian fairy tales in modern culture

[edit]

Collections and modern retellings

[edit]Ukrainian language

[edit]- In 1900, Maria Hrinchenko wrote a collection of Ukrainian fables and folk tales entitled, "Из уст народа" (From the Mouths of the People).[11]

- In the early 1900's, Ukrainian writer, Lesya Ukrainka, wrote a three act play entitled The Forest Song based on the folk mythology surrounding Mavka.[12] In 2023, an animated version entitled "Mavka: The Forest Song" was released.[13][14]

- Professor of folklore, Lidiia Dunayevska, compiled a series of Ukrainian folk tales between 1983 and 2004.[15]

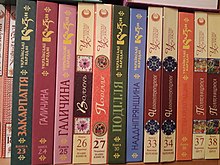

- Ukrainian folklorist, Mykola Zinchuk, collected, edited and published 40 volumes of Ukrainian fairy tales, published by the publishing house, Bukrek between 2003-2019.[16][17]

- Children's book author, Zirka Menzatyuk, uses historical Ukrainian fairy tales as an inspiration for newer writing.[18]

- Edited by Ivan Malkovych, between 2005 and 2012, Ukrainian publisher, A-ba-ba-ha-la-ma-ha, published three volumes of Ukrainian fairy tales in a series called "100 Kazok" (100 fairy tales). Each volume contained 100 fairy tales. 130,000 copies were printed of the first two volumes, and the 2005 volume was a book of the year.[19][20][21]

English language

[edit]- Irina Zheleznova translated a collection of Ukrainian fairy tales into English, entitled Ukrainian Folk Tales, first published by Dnipro Publishers in 1981.[22]

- A 1996 retelling of the Ukrainian fairy tale, The Mitten, by children's author Jan Brett, has become a best-selling classic.[23]

- In 1996, Christina Oparenko retold collected Ukrainian fairy tales in Ukrainian Folk-tales for the series Oxford Myths and Legends.[24]

- In 1997, Barbara Suwyn retold collected Ukrainian fairy tales in The Magic Egg and Other Tales from Ukraine with editing and an introduction by Natalie Kononenko.[25]

- Between 1994 and 2003, Canadian author, Danny Evanishen, wrote and published eleven books containing Ukrainian folk tales retold in English.[26][27][28][29][30]

- In 2024, Harvard University Press will release a translation of Lesya Ukrainka's The Forest Song, with English language translation by Virlana Tkacz and Wanda Phipps.[31]

Other usage in culture

[edit]Some Ukrainian fairy tales have been featured on stamps of Ukrposhta, the national postal service of Ukraine.[32] Many have been retold in Ukrainian animation.[33] The Ukrainian pop band, Kazka, takes its name from the Ukrainian word for fairy tale.[34] Some fairy tale characters have been created in sculpture, such as the statue of Ivasyk-Telesyk in Lviv, Ukraine's Stryiskyi Park.[35]

See also

[edit]- Fairy tale

- Ukrainian Folklore

- History of Ukrainian Animation

- Category:Ukrainian fairy tales

- Russian fairy tale

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Oparenko, Christina (1996). Oxford Myths and Legends: Ukrainian Folk-tales. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0192741683.

- ^ Suwyn 1997, pp. ix-xi

- ^ Suwyn 1997, p. xxiii

- ^ a b c d Suwyn 1997, p. xv-xxiii

- ^ a b Suwyn 1997, p. ix-xi

- ^ a b c Stepanenko, K. (2019-11-25). "Means of Transition between the Worlds (based on English and Ukrainian Fairy Tales)". Science and Education a New Dimension. VII(211) (62): 54–57. doi:10.31174/send-ph2019-211vii62-13. ISSN 2308-5258.

- ^ Bloom, Mia; Moskalenko, Sophia. "How fairy tales shape fighting spirit: Ukraine's children hear bedtime stories of underdog heroes, while Russian children hear tales of magical success". The Conversation. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g Suwyn, Barbara (1997). The Magic Egg and Other Tales from Ukraine. Retold by Barbara J. Suwyn; drawings by author; edited and with an introduction by Natalie O. Kononenko. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited, Inc. p. xxi. ISBN 1563084252.

- ^ a b c d Suwyn 1997, p. xxii.

- ^ Kononenko, Natalie (2011-10-01). "The Politics of innocence: Soviet and Post-Soviet Animation on Folklore topics". Journal of American Folklore. 124 (494): 272–294. doi:10.5406/jamerfolk.124.494.0272. ISSN 0021-8715.

- ^ Lashko, M.V. (July 20, 2023). "До 155 – річчя М. Грінченко" (PDF). Kyiv University named after B. Hrinchenko. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ^ Halley, Catherine (2022-04-15). "Lesya Ukrainka: Ukraine's Beloved Writer and Activist". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 2024-01-12.

- ^ "Mavka's magic. How Ukrainian cartoon fascinated the whole world and why this is just the beginning". RBC-Ukraine. Retrieved 2024-01-12.

- ^ "Mavka: The Forest Song". FILM REVIEW. Retrieved 2024-01-12.

- ^ Астаф’єв, О. Г. (2008). Дунаєвська Лідія Францівна (in Ukrainian). Vol. 8. Інститут енциклопедичних досліджень НАН України. ISBN 978-966-02-2074-4.

- ^ Karpenko, Svitlana (2021-05-24). "АСПЕКТИ ВИВЧЕННЯ УКРАЇНСЬКОЇ НАРОДНОЇ КАЗКИ В ОСТАННЮ ТРЕТИНУ ХХ СТОЛІТТЯ: ФОРМУВАННЯ НОВОЇ ШКОЛИ КАЗКОЗНАВСТВА". Bulletin of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. Literary Studies. Linguistics. Folklore Studies (in Ukrainian). 1 (29): 10–13. ISSN 2709-8494.

- ^ "Видавничий дім "Букрек" - News". bukrek.net. Retrieved 2023-06-04.

- ^ "international literature festival odesa" (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 2023-06-04.

- ^ "100 Fairy Tales. Vol. 1 - "A-BA-BA-GA-LA-MA-GA" Publishers". ababahalamaha.com.ua. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ "100 Fairy Tales. Vol. 2 - "A-BA-BA-GA-LA-MA-GA" Publishers". ababahalamaha.com.ua. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ "100 Fairy Tales. Vol. 3 - "A-BA-BA-GA-LA-MA-GA" Publishers". ababahalamaha.com.ua. Retrieved 2023-06-08.

- ^ Zheleznova, Irina (1985). Ukrainian Folk Tales. Kyiv: Dnipro Publishers.

- ^ "The Mitten 20th Anniversary Edition by Jan Brett". www.penguin.com.au. Retrieved 2023-05-29.

- ^ "Ukrainian folk-tales | WorldCat.org". www.worldcat.org. Retrieved 2023-06-04.

- ^ "The magic egg and other tales from Ukraine | WorldCat.org". www.worldcat.org. Retrieved 2023-06-04.

- ^ "Danny Evanishen". Canadian Books & Authors. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- ^ "Danny Evanishen's home page". www.ethnic.bc.ca. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- ^ Herald, Special to The (2022-03-30). "Rock star volunteer, meet Danny Evanishen". Penticton Herald. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- ^ "Nash Holos Ukrainian Roots Radio: Nash Holos Vancouver 2022-0402 on Apple Podcasts". Apple Podcasts. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- ^ "The Raspberry Hut and Other Ukrainian Folk Tales Retold in English · Canadian Book Review Annual Online". cbra.library.utoronto.ca. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ President and Fellows of Harvard College (January 11, 2024). "The Forest Song: A Fairy Play". Harvard University Press. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ "Ukraine : Stamps : Years List [Theme: Fairy Tales]". colnect.com. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

- ^ Neplii, Anna. "Ukrainian Animated Films Come into Their Own". Get the Latest Ukraine News Today - KyivPost. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

- ^ "Kazka : Ukrainian Pop Band". Talentsofworld Articles. 2021-03-07. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

- ^ "Stryiskyi Park". Lviv Interactive. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

Further reading

[edit]- Andrejev, Nikolai P. [in Russian] (1958). "A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus". Fabula. 1 (2): 228–238. doi:10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228.

- Demedyuk, Мaryna. "УКРАЇНСЬКІ НАРОДНІ КАЗКИ НА СТОРІНКАХ ПОЛЬСЬКОГО ВИДАННЯ «ZBIOR WIADOMOSCI DO ANTROPOLOGII KRAJOWEJ»" [UKRAINIAN FOLKTALES IN POLISH ETHNOGRAPHIC EDITION «ZBIOR WIADOMOSCI DO ANTROPOLOGII KRAJOWEJ»]. In: The Ethnology Notebooks. 2019, № 5 (149), 1200—1204. UDK: 398.21(=161.2):050(438)”187/191”; DOI: https://doi.org/10.15407/nz2019.05.1200.

- Lintur, Petro. A Survey of Ukrainian Folk Tales. Volume 56 - Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Edmonton, Alberta: Research report. Translated by Bohdan Medwidsky. Canada: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta, 1994. ISBN 9781894301565.

External links

[edit]- List of Ukrainian fairy tales at Wikisource (in Ukrainian)