| Urnayr | |

|---|---|

| King of Caucasian Albania | |

| Reign | 350–375 |

| Predecessor | Vache I |

| Successor | Vachagan II |

| Spouse | Daughter of Shapur II |

| Issue | Aswagen |

| House | Arsacid |

| Mother | Sasanian princess |

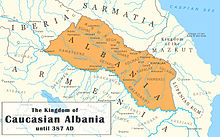

Urnayr (attested only as Old Armenian Ուռնայր Uṙnayr) was the third Arsacid king of Caucasian Albania from approximately 350 to 375.[1] He was the successor of Vache I (r. 336–350).

Biography

[edit]

The Treaty of Nisibis in 299 between the Sasanian King of Kings (shahanshah) Narseh (r. 293–303) and the Roman emperor Diocletian had ended disastrously for the Sasanians, who ceded them huge chunks of their territory, including the Caucasian kingdoms of Armenia and Iberia.[2] The Sasanians would not take part in the political affairs of the Caucasus for almost 40 years.[2]

The modern historian Murtazali Gadjiev argues that it was during this period the Arsacids gained the kingship of Albania, by being appointed as proxies by the Romans in order to gain complete control over the Caucasus.[2] In the 330s, a reinvigorated Iran re-entered the Caucasian political scene, forcing the Arsacid Albanian king Vachagan I (or Vache I) to acknowledge Sasanian suzerainty.[2] Urnayr, whose mother was a Sasanian princess, enjoyed good relations with the Sasanian shahanshah Shapur II (r. 309–379), whose daughter he was given in marriage.[3] The later Arsacid Albanian king Aswagen (r. 415–440) was most likely their son.[4] Urnayr fought alongside Shapur II at the battle of Bagrevand in 372, where he was injured by the Armenian general Mushegh I Mamikonian, who spared him.[5][6] When Urnayr returned to Albania, he sent a message to Mushegh thanking him for sparing his life, and also informed him of a surprise attack planned by Shapur II.[7] Urnayr was succeeded by Vachagan II in c. 375.[1]

Conversion to Christianity

[edit]According to a legend, Urnayr accepted Christianity as state religion of Caucasian Albania in 313 thanks to efforts of Tiridates III of Armenia and Gregory the Illuminator. However, researchers Wolfgang Schulze, Zaza Alexidze and Jost Gippert argued this is unlikely given Urnayr's political career, as well as his contemporariness with Pap of Armenia. It is most likely a later addition to the tradition.[8]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Gadjiev 2020, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d Gadjiev 2020, p. 31.

- ^ Gadjiev 2020, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Gadjiev 2020, p. 32.

- ^ Gadjiev 2020, p. 30.

- ^ Chaumont 1985, pp. 806–810.

- ^ Faustus of Byzantium, History of the Armenians, Book Four, Chapter 5

- ^ Wolfgang, Schulze; Gippert, Jost; Alexidze, Zaza; Mahé, Jean-Pierre (2008–2010). The Caucasian Albanian palimpsests of Mt. Sinai. Turnhout: Brepols. pp. xiii–xv. ISBN 978-2-503-53116-8. OCLC 319126785.

Bibliography

[edit]Ancient works

[edit]- Faustus of Byzantium, History of the Armenians.

Modern works

[edit]- Chaumont, M. L. (1985). "Albania". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 8. pp. 806–810.

- Gadjiev, Murtazali (2020). "The Chronology of the Arsacid Albanians". In Hoyland, Robert (ed.). From Albania to Arrān: The East Caucasus between the Ancient and Islamic Worlds (ca. 330 BCE–1000 CE). Gorgias Press. pp. 29–35. ISBN 978-1463239886.