In Hinduism, Vanara (Sanskrit: वानर, lit. 'forest-dwellers')[1] are either monkeys, apes,[2] or a race of forest-dwelling people.[1]

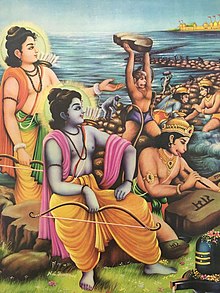

In the epic the Ramayana, the Vanaras help Rama defeat Ravana. They are generally depicted as humanoid apes, or human-like beings.

Etymology

[edit]

There are three main theories about the etymology of the word "Vanara":

- Aiyanar suggests that vanara means "monkey" derived from the word vana ("forest"), Literally meaning "belonging to the forest"[3] Monier-Williams says it is probably derived from vanar (lit. "wandering in the forest") and means "forest-animal" or monkey.[2]

- Devdutt Pattanaik suggests that it derives from the words vana ("forest"), and nara ("man"), thus meaning "forest man" and suggests that they may not be monkeys, which is the general meaning.[4]

- It may be derived from the words vav and nara, meaning "is it a man?" (meaning "monkey")[5] or "perhaps he is man".[6]

Identification

[edit]

Although the word Vanara has come to mean "monkey" over the years and the Vanaras are depicted as monkeys in the popular art, their exact identity is not clear.[7][8] According to the Ramayana, Vanaras were shapeshifters. In the Vanara form, they had beards with extended sideburns, narrowly shaved chin gap, and no moustache. They had a tail and razor-sharp claws. Their skin and skeleton were inforced with an indestructible Vajra, which no earthly element could penetrate. Unlike other exotic creatures such as the rakshasas, the Vanaras do not have a precursor in the Vedic literature.[9] The Ramayana presents them as humans with reference to their speech, clothing, habitations, funerals, weddings, consecrations etc. It also describes their monkey-like characteristics such as their leaping, hair, fur and a tail.[8] Aiyanagar suggests that though the poet of the Ramayana may have known that vanaras were actually forest-dwelling people, he may portrayed them as real monkeys with supernatural powers and many of them as amsas (portions) of the gods to make the epic more "fantastic".[3]

According to one theory, the Vanaras are semi-divine creatures. This is based on their supernatural abilities, as well as descriptions of Brahma commanding other deities to either bear Vanara offspring or incarnate as Vanaras to help Rama in his mission.[8] The Jain re-tellings of Ramayana describe them as a clan of the supernatural beings called the Vidyadharas; the flag of this clan bears monkeys as emblems.[10][11][12][13]: 334 [4]

G. Ramdas, based on Ravana's reference to the Vanaras' tail as an ornament, infers that the "tail" was actually an appendage in the dress worn by the men of the Savara tribe.[8] (The female Vanaras are not described as having a tail.[14][13]: 116 ) According to this theory, the non-human characteristics of the Vanaras may be considered artistic imagination.[7] In Sri Lanka, the word "Vanara" has been used to describe the Nittaewos mentioned in the Vedda legends.[15]

In the Ramayana

[edit]

Vanaras are created by Brahma to help Rama in battle against Ravana. They are powerful and have many godly traits. Taking Brahma's orders, the gods began to parent sons in the zion of Kishkindha (identified with parts of present-day Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Maharashtra). Rama first met them in Dandaka Forest, during his search for Sita.[16] An army of Vanaras helped Rama in his search for Sita, and also in battle against Ravana, Sita's abductor. Nala and Nila built a bridge over the ocean so that Rama and the army could cross to Lanka. As described in the epic, the characteristics of the Vanara include being amusing, childish, mildly irritating, badgering, hyperactive, adventurous, bluntly honest, loyal, courageous, and kind.[17]

Other texts

[edit]The Vanaras also appear in other texts, including Mahabharata. The epic Mahabharata describes them as forest-dwelling, and mentions their being encountered by Sahadeva, the youngest Pandava.[citation needed]

Shapeshifting

[edit]In the Ramayana, the Vanara Hanuman changes shape several times. For example, while he searches for the kidnapped Sita in Ravana's palaces on Lanka, he contracts himself to the size of a cat, so that he will not be detected by the enemy. Later on, he takes on the size of a mountain, blazing with radiance, to show his true power to Sita.[18]

Notable Vanaras

[edit]

- Angada, son of Vali, successor of Sugriva, who helped Rama find his wife Sita

- Anjana, Hanuman's mother

- Hanuman, devotee of the god Rama and son of Vayu

- Kesari, Hanuman's father

- Mainda and Dvivida, sons of Ashvins

- Macchanu, son of Hanuman (per the Cambodian and Thai versions)

- Makardhwaja, son of Hanuman (per the Indian versions)

- Nala, son of Vishwakarma

- Nila, son of Agni

- Rumā, wife of Sugriva

- Sharabha, son of Parjanya

- Sugriva, king of Kishkindha, son of Surya

- Sushena, son of Varuna

- Taar, son of Brihaspati

- Tara, wife of Vali

- Vali, Sugriva's brother and son of Indra

References

[edit]- ^ a b Krishna, Nanditha (1 May 2014). Sacred Animals of India. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-81-8475-182-6.

- ^ a b Monier-Williams, Monier. "Monier-Williams Sanskrit Dictionary 1899 Basic". www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ a b Aiyangar Narayan. Essays On Indo-Aryan Mythology-Vol. Asian Educational Services. pp. 422–. ISBN 978-81-206-0140-6.

- ^ a b Devdutt Pattanaik (24 April 2003). Indian Mythology: Tales, Symbols, and Rituals from the Heart of the Subcontinent. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-59477-558-1.

- ^ Shyam Banerji (1 January 2003). Hindu gods and temples: symbolism, sanctity and sites. I.K. International. ISBN 978-81-88237-02-9.

- ^ Harshananda (Swami.) (2000). Facets of Hinduism. Ramakrishna Math.

- ^ a b Kirsti Evans (1997). Epic Narratives in the Hoysaḷa Temples: The Rāmāyaṇa, Mahābhārata, and Bhāgavata Purāṇa in Haḷebīd, Belūr, and Amṛtapura. BRILL. pp. 62–. ISBN 90-04-10575-1.

- ^ a b c d Catherine Ludvik (1 January 1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

G. Ramadas infers from Ravana's reference to the kapis' tail as an ornament (bhusana) that is a long appendage in the dress worn by men of the Savara tribe.

- ^ Vanamali (25 March 2010). Hanuman: The Devotion and Power of the Monkey God. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-59477-914-5.

- ^ Paula Richman (1991). Many Rāmāyaṇas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. University of California Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-520-07589-4.

- ^ Kodaganallur Ramaswami Srinivasa Iyengar (2005). Asian Variations in Ramayana: Papers Presented at the International Seminar on 'Variations in Ramayana in Asia : Their Cultural, Social and Anthropological Significance", New Delhi, January 1981. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 68–. ISBN 978-81-260-1809-3.

- ^ Valmiki (1996). The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India - Sundarakāṇḍa. Translated and annotated by Robert P. Goldman and Sally J. Sutherland Goldman. Princeton University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-691-06662-0.

- ^ a b Philip Lutgendorf (13 December 2006). Hanuman's Tale : The Messages of a Divine Monkey: The Messages of a Divine Monkey. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-804220-4.

- ^ The Adhyātma Rāmāyaṇa: Concise English Version. M.D. Publications. 1 January 1995. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-85880-77-8.

- ^ C. G. Uragoda (2000). Traditions of Sri Lanka: A Selection with a Scientific Background. Vishva Lekha Publishers. ISBN 978-955-96843-0-5.

- ^ "The Ramayana index".

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Goldman, Robert P. (Introduction, translation and annotation) (1996). Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India, Volume V: Sundarakanda. Princeton University Press, New Jersey. 0691066620. pp. 45–47.

External links

[edit] Media related to Vanara at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vanara at Wikimedia Commons