| |

| Languages | |

|---|---|

| Silesian German | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism, Protestantism |

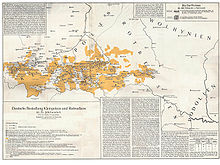

Walddeutsche (lit. "Forest Germans" or Taubdeutsche – "Deaf Germans"; Polish: Głuchoniemcy – "deaf Germans") was the name for a group of German-speaking people, originally used in the 16th century for two language islands around Łańcut and Krosno, in southeastern Poland. Both of them were fully polonised before the 18th century, the term, however, survived up to the early 20th century as the designation na Głuchoniemcach, broadly and vaguely referring to the territory of present-day Sanockie Pits, which has seen a partial German settlement since the 14th century, mostly Slavicised long before the term was coined.

Nomenclature

[edit]The term Walddeutsche – coined by the Polish historians Marcin Bielski (1531),[1] Szymon Starowolski (1632), Bishop Ignacy Krasicki,[2] and Wincenty Pol – also sometimes refers to Germans living between Wisłoka and the San River part of the West Carpathian Plateau and the Central Beskidian Piedmont in Poland.

The Polish term Głuchoniemcy is a sort of pun; it means "deaf-mutes", but sounds like "forest Germans": Niemcy, Polish for "Germans", is derived from niemy ("mute", unable to talk comprehensibly, i.e. in a Slavic language), and głuchy ("deaf",[3] i.e. "unable to communicate") sounds similar to głusz meaning "wood".[4]

History

[edit]

In the 14th century a German settlement called Hanshof existed in the area. The Church of the Assumption of Holy Mary and St. Michael's Archangel in Haczów (Poland), the oldest wooden Gothic temple in Europe, was erected in the 14th century and was added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites in 2003.

Germans settled in the territory of the Kingdom of Poland (territory of present-day Subcarpathian Voivodeship and eastern part of Lesser Poland) from the 14th to 16th centuries (see Ostsiedlung), mostly after the region returned to Polish sphere of influence in 1340, when Casimir III of Poland took the Czerwień towns.

Marcin Bielski states that Bolesław I Chrobry settled some Germans in the region to defend the borders against Hungary and Kievan Rus' but the arrivals were ill-suited to their task and turned to farming.[5] Maciej Stryjkowski mentions German peasants near Przeworsk, Przemyśl, Sanok, and Jarosław, describing them as good farmers.

Some Germans were attracted by kings seeking specialists in various trades, such as craftsmen and miners. They usually settled in newer market and mining settlements. The main settlement areas were in the vicinity of Krosno and some language islands in the Pits and the Rzeszów regions. The settlers in the Pits region were known as Uplander Saxons.[6] Until approximately the 15th century, the ruling classes of most cities in present-day Beskidian Piedmont consisted almost exclusively of Germans.

The Beskidian Germans underwent Polonization in the latter half of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century.[8]

According to Wacław Maciejowski, writing in 1858, the people did not understand German but called themselves Głuchoniemcy.[9] Wincenty Pol wrote in 1869 that their attire was similar to that of the Hungarian and Transylvanian Germans and that their main occupations were farming and weaving. He stated that in some areas the people were of Swedish origin; however, they all spoke flawlessly in a Lesser Poland dialect of Polish.[10] In 1885, Józef Szujski wrote that the Gluchoniemcy spoke only Polish, but there were traces of a variety of original languages which showed that, when they arrived, the term Niemiec was applied to "everyone".[11] In the modern Polish language, Niemiec refers to Germans, but in earlier centuries it was sometimes also used in reference to Hungarians, possibly due to similarity with the word niemy or plural niemi for "mute" or "dumb".[12]

Settlement

[edit]Important cities of this region include Pilzno, Brzostek, Biecz, Gorlice, Ropczyce, Wielopole Skrzyńskie, Frysztak, Jasło, Krosno, Czudec, Rzeszów, Łańcut, Tyczyn, Brzozów, Jaćmierz, Rymanów, Przeworsk, Jarosław, Kańczuga, Przemyśl, Dynów, Brzozów, and Sanok.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Józef Szujski. Die Polen und Ruthenen in Galizien. Kraków. 1896 (Głuchoniemcy/Walddeutsche S. 17.)

- Aleksander Świętochowski. Grundriß der Geschichte der polnischen Bauern, Bd. 1, Lwów-Poznań, 1925; (Głuchoniemcy/Sachsen) S. 498

- Die deutschen Vertreibungsverluste. Bevölkerungsbilanzen für die deutschen Vertreibungsgebiete 1939/50, hrsg. vom Statistischen Bundesamt, Wiesbaden 1958, pages: 275–276 bis 281 "schlesisch- deutscher Gruppe bzw. die Głuchoniemców (Walddeutsche), zwischen Dunajez und San, Entnationalisierung im 16 Jh. und 18 Jh."

- Wojciech Blajer: Bemerkungen zum Stand der Forschungen uber die Enklawen der mittelalterlichen deutschen Besiedlung zwischen Wisłoka und San. [in:] Późne średniowiecze w Karpatach polskich. red. Prof. Jan Gancarski. Krosno, 2007. ISBN 978-83-60545-57-7

Sources and notes

[edit]- ^ Marcin Bielski or Martin Bielski; "Kronika wszystkiego swiata" (1551; "Chronicle of the Whole World"), the first general history in Polish of both Poland and the rest of the world.

- ^ Ignacy Krasicki [in:] Kasper Niesiecki Herbarz [...] (1839–1846) tom. IX, page. 11.

- ^ "Tatra Mountains, between Moravia and the main range of the Carpathians. This population approaches the Slovaks in physical type, as they do geographically. They are said to be in part of German blood, like their neighbors, the Gluchoniemcy, or " Deaf Germans," who also speak Polish. " [in:] William Paul Dillingham. Reports of the Immigration Commission. United States. Immigration Commission (1907–1910). Washington : G.P.O., 1911. p. 260.

- ^ Ut testat Metrika Koronna, 1658, "quod Saxones alias Głuszy Niemcy około Krosna i Łańcuta osadzeni są iure feudali alias libertate saxonica" [in:] dr Henryk Borcz. Parafia Markowa w okresie staropolskim. Markowa sześć wieków. 2005 pp. 72–189

- ^ Władysław Sarna. Opis powiatu krośnieńskiego pod względem geograficzno-historycznym. Przemyśl. 1898. str. 26. Quote: "A dlatego je (Niemców) Bolesław tam osadzał, aby bronili granic od Węgier i Rusi; ale że był lud gruby, niewaleczny, obrócono je do roli i do krów, bo sery dobrze czynią, zwłacza w Spiżu i na Pogórzu, drudzy też kądziel dobrze przędą i przetoż płócien z Pogórza u nas bywa najwięcej"

- '^ [1] Głuchoniemcy (Taubdeutsche) [in:] en. Geographical Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland and other Slavic Lands, ger. Geographisches Ortsnamenlexikon des Polnischen Königreiches. Band II. p. 612 Warsaw. 1889 (Eine Bilddatenbank zur polnischen Geschichte)

- ^ Franciszek Kotula. Pochodzenie domów przysłupowych w Rzeszowskiem. "Kwartalnik Historii Kultury Materialnej" Jahr. V., Nr. 3/4, 1957, S. 557

- ^ "Całkowita polonizacja ludności w omawianym regionach nastąpiła najźniej w XVIII w.[...]" p. 98, and "Eine völlige Polonisierung der Nachkommen der deutschen Ansiedler erfolgte im 18. Jahrhundert und trug zur Verstärkung des Polentums in dem polnisch-ruthenischen Grenzbereich bei. [...]" [in:] Prof. dr Jan Gancarski. Późne średniowiecze w Karpatach polskich. op. cit. Wojciech Blajer: Bemerkungen zum Stand der Forschungen uber die Enklawen der mittelalterlichen deutschen Besiedlung zwischen Wisłoka und San. Edit. Krosno. 2007. ISBN 978-83-60545-57-7 pp. 57–105

- ^ Wacław Aleksander Maciejowski. Historya prawodawstw słowiańskich. 1858. str. 357.

- ^ Wincenty Pol. Historyczny obszar Polski rzecz o dijalektach mowy polskiej. Kraków 1869.

- ^ Józef Szujski. Pisma polityczne. Druk. W.L. Anczyca, Kraków 1885; Józef Szujski. Polacy i Rusini w Galicyi (Die Polen und Ruthenen in Galizien). Druk. W.L. Anczyc, 1896 str. 17. "... od średniego biegu Wisłoka, od Pilzna w górę po Łańcut, szczep zwany Głuchoniemcami, powstały przez osadnictwo XIII i XIV stulecia. Głuchoniemcy mówią tylko po polsku, a resztki rozmaitych ich pierwotnych języków ojczystych świadczą, że za czasów ich przybycia zwano Niemcem każdego ..."

- ^ Blackie, Christina. Geographical etymology