William Collins | |

|---|---|

The sole portrait of William Collins, aged 14 | |

| Born | 25 December 1721 Chichester, Sussex, England |

| Died | 12 June 1759 (aged 37) Chichester, Sussex, England |

| Occupation | Poet |

William Collins (25 December 1721 – 12 June 1759) was an English poet. Second in influence only to Thomas Gray, he was an important poet of the middle decades of the 18th century. His lyrical odes mark a progression from the Augustan poetry of Alexander Pope's generation and towards the imaginative ideal of the Romantic era.

Biography

[edit]Born in Chichester, Sussex, the son of a hatmaker and former mayor of the town, Collins was educated at The Prebendal School,[1] Winchester and Magdalen College, Oxford.[2] While still at the university, he published the Persian Eclogues, which he had begun at school. After graduating in 1743 he was undecided about his future. Failing to obtain a university fellowship, being judged by a military uncle as 'too indolent even for the army', and having rejected the idea of becoming a clergyman, he settled for a literary career and was supported in London by a small allowance from his cousin, George Payne. There he was befriended by James Thomson and Dr Johnson as well as the actors David Garrick and Samuel Foote.

Following the failure of his collection of odes in 1747, Collins' discouragement, aggravated by drunkenness, so unsettled his mind that he eventually sank into insanity and by 1754 was confined to McDonald's Madhouse in Chelsea. From there he moved to the care of an elder sister in Chichester, who lived with her clergyman husband within the cathedral precincts. There Collins continued to stay, with periods of lucidity during which he was visited by the Warton brothers. On his death in 1759, he was buried in St Andrew-in-the-Oxmarket Church.

Poems

[edit]Eclogues

[edit]The pastoral eclogue had been a recognised genre in English poetry for the two centuries before Collins wrote his, but in the 18th century there was a disposition to renew its subject matter. Jonathan Swift, John Gay and Mary Wortley Montagu had all transposed rural preoccupations to life in London in a series of "town eclogues"; at the same period William Diaper had substituted marine divinities for shepherds in his Nereides: or Sea-Eclogues (1712).[3] Collins' Persian Eclogues (1742) also fell within this movement of renewal. Though written in heroic couplets, their Oriental settings are explained by the pretence that they are translations. Their action takes place in "a valley near Bagdat" (1), at midday in the desert (2), and within sight of the Caucasus mountains in Georgia (3) and war-torn Circassia (4).[4]

The poems were sufficiently successful for a revised version to be published in 1757, retitled as Oriental Eclogues.[5] In the following decades they were frequently republished and on the Continent were twice translated into German in 1767 and 1770.[6] They were also an influence on later eclogues that were given exotic locations. The three dating from 1770 by Thomas Chatterton had purely imaginary African settings and their versification was distinguished by "crude imaginative force and incoherent, almost Ossianic, fervor".[7] By contrast, the Oriental Eclogues of Scott of Amwell (1782) can stand "favourable comparison" with Collins' and their background details are supported by contemporary scholarship.[8]

In addition, Scott's introductory "Advertisement" justifies his poems as both a homage to and variation upon the work of Collins. The Oriental Eclogues of the elder poet, he says, "have such excellence, that it may be supposed they must preclude the appearance of any subsequent Work with the same title. This consideration did not escape the Author of the following Poems; but, as the scenery and sentiment of his Predecessor were totally different from his own, he thought it matter of little consequence."[9] Scott's poems are set in Asian areas well beyond Persia's former dominions: in Arabia in his first, Bengal in his second and Tang dynasty China in the time of Li Bai (Li Po) in his third.[10]

Odes

[edit]Collins' Odes also fit within the context of a movement towards the renewal of the genre, although in this case it was largely formal and showed in his preference for pindarics and occasionally dispensing with rhyme. Here he was in the company of Thomas Gray, Mark Akenside, and his Winchester schoolfellow Joseph Warton.[11] At first Collins intended his Odes on Several Descriptive and Allegorical Subjects (1747) to be jointly published with Warton's Odes on Various Subjects (1746) until Warton's publisher refused the proposal. Following their appearance, Gray commented in a letter that each poet "is the half of a considerable Man, & one the Counter-part of the other. [Warton] has but little Invention, very poetical choice of Expression, & a very good Ear; [Collins] a fine Fancy, model'd upon the Antique, a bad Ear, a great variety of Words & Images, with no Choice at all. They both deserve to last some years, but will not."[12] Moreover, their new manner and stylistic excess lent themselves to burlesque parody, and one soon followed from a university miscellany in the shape of an "Ode to Horror: In the Allegoric Descriptive, Alliterative, Epithetical, Fantastic, Hyperbolical, and Diabolical Style".[13] Rumour had it even then that the culprit was Warton's brother Thomas, and his name was coupled with it in later reprintings.

As Gray had forecast, little favourable notice was taken at the time of poems so at odds with the Augustan spirit of the age, characterised as they were by strong emotional descriptions and the personal relationship to the subject allowed by the ode form. Another factor was dependence on the poetic example of Edmund Spenser and John Milton, where Collins' choice of evocative word and phrase, and his departures from prose order in his syntax, contributed to his reputation for artificiality.[14][15] Warton was content to refuse later republication of the products of his youthful enthusiasm, but Collins was less resilient. Although he had many projects in his head in the years that followed, few came to fruition. Republication of his eclogues apart, his closest approach to success was when the composer William Hayes set "The Passions" as an oratorio that was received with some acclaim.[16]

Collins' only other completed poem afterwards was the "Ode written on the death of Mr Thomson" (1749), but his unfinished works suggest that he was moving away from the contrived abstraction of the Odes and seeking inspiration in an idealised time uncorrupted by the modern age. Collins had showed the Wartons an "Ode on the Popular Superstitions of the Highlands of Scotland, Considered as the Subject of Poetry", an incomplete copy of which was discovered in Scotland in 1788. Unfortunately, a spuriously completed version, published in London the same year as the Scottish discovery, was passed off as genuine in all collections of Collins until the end of the 19th century.[17][18] The former text was then restored in scholarly editions and confirmed by the rediscovery of the original manuscript in 1967.[19] The poem appealed to bardic subject matter "whose power had charm’d a Spenser’s ear" to the imaginative rehabilitation of true poetry.

Another indication of the new direction his work was taking was the "Ode on the Music of the Grecian Theatre" that Collins proposed sending to Hayes in 1750. There, he asserted, "I have, I hope, Naturally introduc’d the Various Characters with which the Chorus was concern’d, As Oedopus, Medea, Electra, Orestes, &c &c. The Composition too is probably more correct, as I have chosen the ancient Tragedies as my Models."[20] But all that has remained to substantiate this large claim is an 18-line fragment titled "Recitative Accompanied" and beginning "When Glorious Ptolomy by Merit rais'd".[21]

Legacy

[edit]Thomas Warton in his History of English Poetry (1774) made retrospective amends for his youthful lampoon by speaking there of "My late lamented friend Mr William Collins, whose Odes will be remembered while any taste for true poetry remains".[22] Nevertheless, it was not until a few years after the poet's death that his work was collected in the edition of John Langhorne in 1765, after which it slowly gained more recognition, although never without criticism. While Dr Johnson wrote a sympathetic account of his former friend in Lives of the Poets (1781), he echoed Gray in dismissing the poetry as contrived and poorly executed.[23] At a much later date, Charles Dickens was dismissive for other reasons in his novel Great Expectations. There Pip describes his youthful admiration for a recitation of Collins' The Passions and commented ruefully, "I particularly venerated Mr. Wopsle as Revenge throwing his blood-stain'd Sword in Thunder down, and taking the War-denouncing Trumpet with a withering Look. It was not with me then as it was in later life, when I fell into the society of the Passions and compared them with Collins and Wopsle, rather to the disadvantage of both gentlemen".[24]

But among the posthumous enthusiasts for Collins' poetry had been Scott of Amwell whose "Stanzas written at Medhurst, in Sussex, on the Author's return from Chichester, where he had attempted in vain to find the Burial-place of Collins" was published in 1782. This charged that while the tombs of the unworthy were "by Flatt'ry's pen inscrib'd with purchas'd praise", those possessing genius and learning were "Alive neglected, and when dead forgot".[25]

That state of affairs was remedied by the commissioning of a monument to Collins in Chichester Cathedral in 1795, which brought a later tribute from the Wesleyan preacher Elijah Waring in "Lines, composed on paying a visit to the tomb of Collins, in Chichester Cathedral". This, after initially noting the subject matter of the Odes, soon turned to a celebration of the poet's faith in religion and his exemplary death.[26] The poem is a response to John Flaxman's design for the memorial, which depicted Collins seated at a table and studying the New Testament. This in turn was based on the anecdote perpetuated by Johnson in his life of the poet that he "travelled with no other book than an English Testament, such as children carry to the school. When his friend took it into his hand, out of curiosity to see what companion a man of letters had chosen, 'I have but one book,' said Collins, 'but that is the best.'"

Flaxman's monument to the poet was funded by public subscription. As well as showing the poet in pious contemplation, it depicts a lyre left upon the floor, accompanied by a scrolled copy titled "The Passions: an ode", representing his abandonment of poetry. On the ridge over the memorial tablet, the female figures of love and piety are lying with arms about each other.[27] Beneath is an epitaph by William Hayley which also makes reference to Johnson's anecdote of the poet "Who in reviving reason's lucid hours, | Sought on one book his troubled mind to rest, | And rightly deem'd the book of God the best."[28]

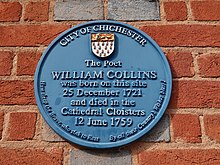

St Andrews, the church where Collins was buried, was converted to an arts centre in the 1970s, but the poet is now commemorated by a window on the south side drawing on the Flaxman memorial and showing him at his reading.[29] There is also a blue plaque placed on the Halifax building in East Street on the site of his birthplace.[30]

Works

[edit]- Persian Eclogues (1742); these were revised as Oriental Eclogues in 1759.

- Verses humbly address'd to Sir Thomas Hanmer on his edition of Shakespeare's works (1743); republished in a revised edition in 1744, in which "A Song from Shakespeare's Cymbeline" was included.

- Odes on Several Descriptive and Allegoric Subjects (1746)

- Ode on the Death of Thomson (1749)

- Ode on the Popular Superstitions of the Highlands (written 1750, unpublished until later editions)

Editions

[edit]- Poetical works of William Collins, ed. John Langhorne, originally published in 1765; several editions followed, to which Dr Johnson's life of Collins was added.[31]

- A scholarly edition was published in The Poetical Works of Gray and Collins (ed. Austin Poole) by Oxford University Press in 1926; from the same press there followed the definitive edition of The Works of William Collins (ed. Wendorf & Ryskamp) in 1979.

Musical settings

[edit]Because the song "To fair Fidele's grassy tomb" (alternatively known as "A Song or Dirge from Shakespear's Cymbeline") was included in 18th century adaptations of the play, settings by several composers were common at the time. Thomas Arne's was the earliest, included in his Second Volume of Lyric Harmony (1746),[32][33] followed by others by William Jackson of Exeter (c. 1755), Maria Hester Park (1790) and Venanzio Rauzzini (c. 1805).[34] There were also settings of the song as a glee by Benjamin Cooke, as well as of Arne's, as harmonised by Thomas Billington (c.1790).[35]

Following the already mentioned setting of "The Passions" by William Hayes, other composers took up the poem, including Benjamin Cooke (1784);[36] Laura Wilson Barker (1846);[37] Alice Mary Smith as a cantata for soloists, choir and orchestra (1882);[38] and Frederic Cowen for chorus and orchestra (1898).[39] In addition, the final section of the poem was set for choral performance by Zoltán Kodály under the title An Ode for Music (1963).[40][41] One other poem by Collins, "Ode to Evening", was set by Granville Bantock as the introductory piece in his Choral Suite for men's voices (1926).[42]

References

[edit]- ^ Collins, William (1898). The Poems. Georg Olms Verlag. p. xii. ISBN 978-3-487-04665-5.

- ^ "William Collins". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ Huber, Alexander. "Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive / Authors / William Diaper". www.eighteenthcenturypoetry.org. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Renascence Editions

- ^ Text at 18th Century Poetry Archive

- ^ Sandro Jung, "William Hymers and the editing of William Collins' poems, 1765–1797", Modern Language Review 106.2 (2011), p.336

- ^ Martha Pike Conant, The Oriental Tale in England in the Eighteenth Century, Routledge 2019, "African Eclogues"

- ^ R. R. Agrawal, The Medieval Revival and Its Influence on the Romantic Movement, Abhinav Publications 1990, pp.128 – 134

- ^ Quoted on Spenserians

- ^ The Cabinet of Poetry: Containing the Best Entire Pieces to be Found in the Works of the British Poets, London 1808, Volume VI, pp.74 – 86

- ^ Ralph Cohen, "The return of the ode", The Cambridge Companion to Eighteenth-Century Poetry (CUP, 2001), pp.202ff

- ^ Hysham, Julia, "Joseph Warton's Reputation as a Poet", Studies in Romanticism, vol. 1.4, 1962, [www.jstor.org/stable/25599562, cited on p.220]

- ^ The Student. Or, the Oxford and Cambridge Monthly Miscellany 2 (1751) pp.313-15

- ^ Albert Charles Hamilton, The Spenser Encyclopedia, University of Toronto 1997, p.177

- ^ Nalini Jain, John Richardson, Eighteenth Century English Poetry, Routledge 2016, pp.418 – 424

- ^ The piece has recently been revived by the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis. Complete excerpts are available on YouTube and short excerpts from the whole work at Chandos Music

- ^ Evan Gottlieb, Feeling British: Sympathy and National Identity in Scottish and English Writing, 1707-1832, Bucknell University Press, 2007, pp.137-143

- ^ The London text of the "Superstitions Ode" can be read on the Spenserians site

- ^ Sigworth, Oliver F. (1981). "The Works of William Collins by Richard Wendorf, Charles Ryskamp". Modern Philology. 79 (1): 86–89. doi:10.1086/391104. JSTOR 437371.

- ^ Quoted in Simon Heighes, The Lives and Works of William and Philip Hayes, 1995, p.219

- ^ Ilaria Natali, "Remov'd from human eyes": Madness and Poetry 1676-1774, Firenze University Press 2016, 127-9

- ^ Richard Wendorf, "'Poor Collins' Reconsidered", Huntington Library Quarterly, vol. 42.2, 1979, [www.jstor.org/stable/3817498, cited on p.96]

- ^ The Works of Samuel Johnson, vol.2, pp.275-6

- ^ "Great Expectations Summary - eNotes.com". eNotes. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Text at Spenserians

- ^ Published in The Poetical Magazine 3 (1810), pp.252-54

- ^ Thomas Walker Horsfield, The History, Antiquities, and Topography of the County of Sussex (1835), vol.2, pp.13-14

- ^ http://www.artandarchitecture.org.uk/images/conway/93f41c13.html [bare URL]

- ^ "The Oxmarket Centre of Arts, Chichester". Sussex ArtBeat. 28 February 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ The History Guide

- ^ William Collins, John Langhorne (12 May 1848). "Poetical Works of William Collins: With Life of the Author". Leavitt, Trow & Co. Retrieved 12 May 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Hyperion Records

- ^ Complete performance on YouTube

- ^ Choral Wiki

- ^ Notamos

- ^ Internet Archive

- ^ Composers: classical music

- ^ "Theodore Front Musical Literature - Ode To The Passions / edited by Ian Graham-Jones". www.tfront.com. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Novello edition

- ^ Score at Stretta Music

- ^ A performance on YouTube

- ^ Google Play

External links

[edit] Works by or about William Collins at Wikisource

Works by or about William Collins at Wikisource Quotations related to William Collins at Wikiquote

Quotations related to William Collins at Wikiquote Media related to William Collins (poet) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to William Collins (poet) at Wikimedia Commons- William Collins at the Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA)

- Works by William Collins at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Collins at the Internet Archive

- Works by William Collins at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Gosse, Edmund William (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). pp. 692–693.