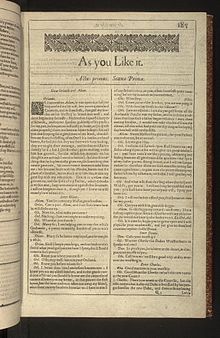

Wilton House is an English country house at Wilton near Salisbury in Wiltshire, which has been the country seat of the Earls of Pembroke for over 400 years. It was built on the site of the medieval Wilton Abbey. Following the dissolution of the monasteries, Henry VIII presented Wilton Abbey and its attached estates to William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke. The house has literary associations. Shakespeare's theatre company performed there (As You Like It may have been the chosen work),[1][2] and there was an important literary salon culture under its occupation by Mary Sidney, wife of the second Earl.[3]

The present Grade I listed house is the result of rebuilding after a 1647 fire, although a small section of the house built for William Herbert survives; alterations were made in the early 19th and early 20th centuries. The house stands in gardens and a park which are also Grade I listed. While still a family home, the house and grounds are open to visitors during the summer months.

Tudor phase

[edit]

William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke, the scion of a distinguished family in the Welsh marches, was a favourite of King Henry VIII. Following a recommendation to Henry by King Francis I of France, whom Herbert had served as a soldier of fortune, he was granted arms. In 1538, he married Anne Parr, daughter of Sir Thomas Parr of Kendal and sister of the future queen consort Catherine Parr (1543–1547) and Sir William Parr, 1st Baron Parr of Kendal (later Marquess of Northampton).[4][5]

Following the dissolution of the monasteries, Henry presented Wilton Abbey and its attached estates to Herbert. The granting of such an estate was an accolade and evidence of his position at court. The first grants, dated March and April 1542, include the site of the late monastery, the manor of Washerne adjoining, and also the manors of Chalke. These were given to "William Herbert, Esquire and Anne his wife for the term of their lives with certain reserved rents to King Henry VIII."[6] When Edward VI re-granted the manors to the family, it was explicitly "to the aforenamed Earl, by the name of Sir William Herbert, knight, and the Lady Anne his wife and the heirs male of their bodies between them lawfully begotten."[7]

Herbert built Wilton House, probably on the same site as the abbey, between 1544 and 1563.[8] According to John Aubrey's Brief Life, Herbert was briefly dispossessed under Mary I of England:

"In Queen Mary's time, upon the return of the Catholique religion, the nunnes came again to Wilton Abbey; and this William, Earl of Pembroke, came to the gate which lookes towards the court by the street, but now is walled up, with his cappe in his hand, and fell upon his knees to the Lady Abbess and nunnes, crying peccavi. Upon Queen Mary's death, the Earl came to Wilton (like a tygre) and turned them out crying, 'Out, ye whores! to worke, to worke—ye whores, goe spinne!"[9]

The Wilton Circle were an influential group of 16th-century English poets, led by Mary Sidney and based at Wilton. Sidney turned Wilton into a "paradise for poets", and the circle included Edmund Spenser, Michael Drayton, Sir John Davies, Abraham Fraunce, and Samuel Daniel.

They are described as "the most important and influential literary circle in English history" and Mary Sidney has been called a "patroness of the muses".

Hans Holbein

[edit]It has long been claimed, without proof, that Hans Holbein the Younger re-designed the abbey as a rectangular house around a central courtyard, which is the core of the present house. Holbein died in 1543, so his designs for the new house would have had to be very speedily executed. However, the highly ornamented entrance porch to the new mansion, removed from the house around 1800 and later transformed into a garden pavilion, is to this day known as the "Holbein Porch"[10] – a perfect example of the blending of the older Gothic and the brand-new Renaissance style.[citation needed]

Whoever the architect, a great mansion arose, an early prodigy house by a courtier of the Tudors. Today only one other part of the Tudor mansion survives: the great tower in the centre of the east facade. With its central arch (once giving access to the court beyond) and three floors of oriel windows above, the tower is slightly reminiscent of the entrance at Hampton Court. It is flanked today by two wings in a loose Georgian style, each topped by an Italianate pavilion tower.

Royal court at Wilton in 1603

[edit]

The Tudor house built by William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke, in 1551 lasted 80 years. King James, Anne of Denmark, and Prince Henry stayed at Wilton in November and December 1603, due to plague in London and gave an audience to two Venetian ambassadors, Nicolò Molin and Piero Duodo.[11] The court at Wilton was entertained by John Heminges and the King's Men who were paid £30 for a play on 2 December.[12] They are said to have performed As You Like It.[13]

Inigo Jones

[edit]On the succession of the 4th Earl in 1630, he decided to pull down the southern wing and erect a new complex of staterooms in its place. It is now that the second great name associated with Wilton appears: Inigo Jones.

The architecture of the south front is in severe Palladian style, described at the time as in the "Italian Style;" built of the local stone, softened by climbing shrubs, it is quintessentially English to our eyes today. While the remainder of the house is on three floors of equal value in the English style, the south front has a low rusticated ground floor, almost suggesting a semi-basement. Three small porches project at this level only, one at the centre, and one at each end of the facade, providing small balconies to the windows above. The next floor is the piano nobile, at its centre the great double-height Venetian window, ornamented at second floor level by the Pembroke arms in stone relief. This central window is flanked by four tall sash windows on each side. These windows have low flat pediments. Each end of the facade is defined by "corner stone" decoration giving a suggestion that the single-bay wings project forward. The single windows here are topped by a true pointed pediment.

Above this floor is a further almost mezzanine floor, its small unpedimented windows aligning with the larger below, serve to emphasise the importance of the piano nobile. The roofline is hidden by a balustrade. Each of the terminating 'wings' is crowned by a one-storey, pedimented tower resembling a Palladian pavilion. At the time, his style was an innovation. Just thirty years earlier, Montacute House, exemplifying the English Renaissance, had been revolutionary; only a century earlier, the juxtaposing mass of wings that is Compton Wynyates, one of the first houses to be built without complete fortification, had just been completed and was considered modern.

Attributing the various architectural stages can be difficult, and the degree to which Inigo Jones was involved has been questioned. Queen Henrietta Maria, a frequent guest at Wilton, interrogated Jones about his work there. At the time (1635) he was employed by her, completing the Queen's House at Greenwich. It seems at this time Jones was too busy with his royal clients and did no more than provide a few sketches for a mansion, which he then delegated for execution to an assistant Isaac de Caus (sometimes spelt 'Caux'), a Frenchman and landscape gardener from Dieppe.

A document that Howard Colvin found at Worcester College library in Oxford in the 1960s confirmed not only de Caus as the architect, but that the original plan for the south facade was to have been over twice the length of that built; what we see today was intended to be only one of two identical wings linked by a central portico of six Corinthian columns. The whole was to be enhanced by a great parterre whose dimensions were 1,000 feet by 400 feet. This parterre was in fact created and remained in existence for over 100 years. The second wing however failed to materialise – perhaps because of the 4th Earl's quarrel with King Charles I and subsequent fall from favour, or the outbreak of the Civil War; or simply lack of finances.

It is only now that Inigo Jones may have taken a firmer grip on his original ideas. Seeing De Caus' completed wing standing alone as an entirety, it was considered too plain – De Caus' original plan was for the huge facade to have a low pitched roof, with wings finishing with no architectural symbols of termination. The modifications to the completed wing were of a balustrade hiding the weak roof line and Italianate, pavilion-like towers at each end. The focal point became not a portico but the large double height Venetian window. This south front (illustration above), has been deemed an architectural triumph of Palladian architecture in Britain, and it is widely believed that the final modifications to the work of De Caus were by Inigo Jones himself.

Within a few years of the completion of the new south wing in 1647, it was ravaged by fire. The seriousness of the fire and the devastation it caused is now a matter of some dispute. The architectural historian Christopher Hussey has convincingly argued that it was not as severe as some records have suggested. What is definite is that Inigo Jones now working with another architect John Webb (his nephew by marriage to Jones' niece) returned once again to Wilton. Because of the uncertainty of the fire damage to the structure of the house, the only work that can be attributed with any degree of certainty to the new partnership is the redesign of the interior of the seven state-rooms contained on the piano nobile of the south wing; and even here the extent of Jones' presence is questioned. It appears he may have been advising from a distance, using Webb as his medium.

The state rooms

[edit]

The seven state rooms contained behind the quite simple Mannerist south front of Wilton House are equal to those in any of the great houses of Britain. State rooms in English country houses were designed, named, and reserved for the use of the visiting members of the royal family. State rooms usually occupy an entire facade of a house, and are nearly always of an odd number because the largest and most lavish room (at Wilton the famed Double Cube Room) is placed at the centre of the facade, with symmetrical sequences of smaller (but still very grand) rooms leading from the central room to either side, ending at the state bedrooms, which are at either end of the facade. The central salon was a gathering place for the court of the honoured guest. The comparatively smaller rooms in between the central room and the state bedrooms were designated for the sole use of the occupant of each bedroom, and would have been used for private audiences, withdrawing rooms, and dressing rooms. They were not for public use.

In most English houses today the original intention has been lost, and these rooms have usually become a meaningless succession of drawing rooms; this is certainly true at both Wilton House and Blenheim Palace. The reason for this is that, over time, the traditional occupants of the state bedrooms began to prefer the comfort of a warmer, more private bedroom on a quiet floor with an en-suite bathroom. By the Edwardian Period, large house-parties had adapted the state rooms to use as salons for playing bridge, dancing, talking, and generally amusing themselves.

The magnificent state rooms at Wilton, designed by Inigo Jones and one or another of his partners, are:

- The Single Cube Room: This room is a complete cube 30 ft long (9 m), wide and high, has gilded and white pine panelling, and is carved from dado to cornice. The white marble chimney piece was designed by Inigo Jones himself. The room has a painted ceiling, on canvas, by the Mannerist Italian painter Cavalier D'Arpino, representing Daedalus and Icarus. This room, hung with paintings by Lely and Van Dyck, is the only room thought to have survived the fire of 1647, and thus the only remaining interior of Jones and De Caus.

- The Double Cube Room: The great room of the house. It is 60 ft long (18 m), 30 ft wide (9 m) and 30 ft high (9 m). It was created by Inigo Jones and Webb circa 1653. The pine walls, painted white, are decorated with great swags of foliage and fruit in gold leaf. The gilt and red velvet furniture complements the collection of paintings by Van Dyck of the family of Charles I and the family of his contemporary Earl of Pembroke. Between the windows are mirrors by Chippendale and console tables by William Kent. The coffered ceiling, painted by Thomas de Critz, depicts the story of Perseus. Here again is another anomaly which makes one question the true involvement of Jones: the great Venetian window, centrepiece of the south front and centrepiece of the double cube room, is not the dead centre of the room's outer wall; the other windows in the room are not symmetrically placed; and the central fireplace and Venetian window are not opposite each other as the proportions of a room designed as an architectural feature in itself would demand.

- The Great Anteroom: Before the modifications to the house in 1801, a great staircase of state led from this room to the courtyard below: this was the entrance to the state apartments. Here hangs one of Wilton's greatest treasures: the portrait of his mother by Rembrandt.

- The Colonnade Room: This was formerly the state bedroom. The series of four gilded columns at one end of the room would have given a theatrical touch of importance to the now-missing state bed. It is furnished today with 18th-century furniture by William Kent. The room is hung with paintings by Reynolds and has a ceiling painted in an 18th-century theme of flowers, monkeys, urns, and cobwebs.

Other rooms are:

- The Corner Room: The ceiling in this room, representing the conversion of Saint Paul, was painted by Luca Giordano. The walls of the room are covered in red damask and adorned with small paintings by, among others, Rubens and Andrea del Sarto.

- The Little Ante Room: The white marble fireplace in this room, with inserts of black marble, is almost certainly by Inigo Jones. The panels in the ceiling were painted by Lorenzo Sabbatini (1530–1577) and therefore are far older than this part of the house; again there are paintings by Van Dyck and Teniers.

- The Hunting Room: This room, not shown to the public, is used as a private drawing room by the Herbert family. It is a square room with white panelling and gilded mouldings. The greatest feature of the room is the set of panels depicting hunting scenes by Edward Pierce painted circa 1653. These panels are set into the panelling rather than framed in the conventional sense.

Inigo Jones was a friend of the Herbert family. It has been said that Jones' original studying in Italy of Palladio and the other Italian masters was paid for by the 3rd Earl, father of the builder of the south front containing the state rooms. There are in existence designs for gilded doors and panels at Wilton annotated by Jones. It seems likely that Jones originally sketched some ideas for de Caus, and following the fire conveyed through Webb some further ideas for tidying the house and its decorations. Fireplaces and decorative themes can be executed at long distance. The exact truth of the work by Jones will probably never be known.

In 1705, following a fire, the 8th Earl rebuilt some of the oldest parts the house, making rooms to display his newly acquired Arundel marbles, which form the basis for the sculpture collection at Wilton today. Following this Wilton remained undisturbed for nearly a century.

19th century and James Wyatt

[edit]

The 11th Earl (1759–1827) called upon James Wyatt in 1801 to modernise the house, and create more space for pictures and sculptures. The final of the three well-known architects to work at Wilton (and the only one well documented) was to prove the most controversial. His work took eleven years to complete.

James Wyatt was an architect who often employed the neo-classical style, but at Wilton for reasons known only to architect and client he used the Gothic style. Since the beginning of the 20th century his work at Wilton has been condemned by most architectural commentators. The negative points of his 'improvements' to modern eyes are that he swept away the Holbein porch, reducing it to a mere garden ornament, replacing it with a new entrance and forecourt. This entrance forecourt created was entered through an 'arc de triumph' which had been created as an entrance to Wilton's park by Sir William Chambers circa 1755. The forecourt was bounded by the house on one side, with wings of fake doors and windows extending to form the court, all accessed by Chambers's repositioned arch, crowned by a copy of the life-size equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius. While not altogether displeasing as an entrance to a country house, the impression created is more of a hunting estate in Northern France or Germany.

The original Great Hall of the Tudor house, the chapel and De Caus-painted staircase to the state apartments were all swept away at this time. A new Gothic staircase and hall were created in the style of Camelot. The Tudor tower, now the last remnant of William Herbert's house, escaped unscathed except for the addition of two 'medieval' statues at ground floor level.

There was however one huge improvement created by Wyatt – the cloisters. This two-storeyed gallery which was built around all four sides of the inner courtyard, provided the house with not only the much needed corridors to link the rooms, but also a magnificent gallery to display the Pembroke collection of classical sculpture. Wyatt died before completion, but not before he and Lord Pembroke had quarrelled over the designs and building work. The final touches were executed by Wyatt's nephew Sir Jeffry Wyatville. Today nearly two hundred years later Wyatt's improvements do not jar the senses as much as they did those of the great architectural commentators James Lees-Milne and Sir Sacheverell Sitwell writing in the 1960s. That Wyatt's works are not in the same league of style as the south front, and the Tudor tower, is perhaps something for future generations to judge.

Secondary rooms

[edit]Wilton is not the largest house in England by any means: compared to Blenheim Palace, Chatsworth, Hatfield and Burghley House, its size is rather modest. However, aside from the magnificent state rooms, a number of secondary rooms are worthy of mention:

- The Front Hall: redesigned by Wyatt, access is gained from this room to the cloisters through two Gothic arches. The room is furnished with statuary; the dominating piece a larger than life statue of William Shakespeare designed by William Kent in 1743. It commemorates an unproved legend that Shakespeare came to Wilton and produced one of his plays in the courtyard.

- The Upper Cloisters: designed by Wyatt but completed circa 1824 by Wyatville in the Gothic style contain neoclassical sculpture, and curios such as a lock of Queen Elizabeth I's hair, and Napoleon I's dispatch box and paintings by the Brueghel brothers.

- The Staircase: Designed by Wyatt, it replaces the muralled state staircase swept away during the 'improvements'. The imperial staircase is lined with family portraits by Lely. Also hanging here is a portrait of Catherine Woronzow, the only sister of 1st Prince Vorontsov and the wife of the 11th Earl; her Russian sleigh is displayed in the cloisters.

- The Smoking Rooms: These rooms are in the wing attributed to Inigo Jones and John Webb linking to the south front. The cornices and doors are attributed to Jones. The larger of the two rooms contains a set of fifty-five gouache paintings of an equestrian theme painted in 1755. The room is furnished with a complete set of bureau, cabinets and break-front bookcases made for the room by Thomas Chippendale.

- The Library: A large book-lined room over 20 yards long, with views to a formal garden and vista leading to the 'Holbein' porch. This is used as a private room and not shown to the public.

- The Breakfast Room: A private small low-ceilinged room on the rustic floor of the south front. In the 18th century this was the house's only bathroom; more of an indoor swimming pool, the sunken plunge pool was heated and the room decorated in the Pompeian style complete with Corinthian columns. Converted by the Russian Countess of Pembroke to a breakfast room circa 1815, it is today wallpapered in a Chinese design, the paper being an exact copy of that used in the original 1815 decoration of the room. The 18th century furniture of a simulated-bamboo, Gothic style gives this private dining room a distinct oriental atmosphere.

Associated buildings

[edit]Entrance arch and lodges

[edit]The north entrance to the house and the forecourt within it were created by Wyatt c.1801. The centrepiece is an ashlar arch, designed c.1758–62 by Sir William Chambers as a garden feature, and carrying a lead statue (probably of earlier date) of Marcus Aurelius on horseback. The structure has a pair of Corinthian columns at each corner and a dentil cornice, and the inner arch is on Doric columns and 18th-century wrought-iron gates. On each side Wyatt added a single-storey lodge in ashlar, with a balustraded parapet.[14] The whole is Grade I listed.[14]

Former stables

[edit]Washern Grange, south of the house and on the other side of the Nadder, is said to be a 1630s rebuilding of an earlier stable block, and incorporates a 14th-century barn which presumably belonged to the abbey. Built in brick with stone dressings and now several dwellings, the complex is Grade I listed.[15] Washern was a manor (Waisel in Domesday Book)[16] and later a suburb of Wilton, which was absorbed into the grounds of Wilton House.[17]

Gardens and grounds

[edit]-

Wilton House framed by trees

-

Wilton estate gardens

-

Trees on the estate

-

Footbridge over creek

-

The Palladian bridge

-

Fountain

The house is renowned for its gardens. Isaac de Caus began a project to landscape them in 1632, laying out one of the first French parterres seen in England. An engraving of it made the design influential after the royal Restoration in 1660, when grand gardens began to be made again. The original gardens included a grotto and water features.

Palladian Bridge

[edit]After the parterre had been replaced by turf, the Palladian Bridge (1736–37, Grade I listed)[18] over the little River Nadder, 90m south of the house, was designed by the 9th Earl in collaboration with architect Roger Morris. Balustraded stairs on each side lead through a pedimented arch into an open pavilion, and the central balustraded span has a high roof supported by a five-bay Ionic colonnade. The design was in part based on a rejected design by Palladio for the Rialto Bridge, Venice.[18]

A copy of the bridge was erected at the much-visited garden of Stowe in Buckinghamshire, and three more were erected: at Prior Park, Bath; Hagley, Worcestershire; and Amesbury Abbey. Empress Catherine the Great commissioned another copy, known as the Marble Bridge, to be set up at the landscape park of Tsarskoye Selo.[19]

Lost settlement

[edit]The park includes an area formerly occupied by much of the village of Fugglestone, which was cleared away, including the site of a medieval leper hospital called the Hospital of St Giles.[20]

Recent developments

[edit]

In the late 20th century, the 17th Earl had a garden created in Wyatt's entrance forecourt, in memory of his father, the 16th Earl. This garden enclosed by pleached trees, with herbaceous plants around a central fountain, has done much to improve and soften the severity of the forecourt.

In 1987 the park and gardens were listed Grade I on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of special historic interest.[21]

Today

[edit]The house was recorded as Grade I listed in 1951.[8] The house and gardens have been open to the public since that year,[22] usually during the summer months.[23]

Wilton was described by the architectural historian Sir John Summerson in 1964 as:[24][better source needed]

- ...the bridge is the object which attracts the visitor before he has become aware of the Jonesian facade. He approaches the bridge and, from its steps, turns to see the facade. He passes through and across the bridge, turns again and becomes aware of the bridge, the river, the lawn and the façade as one picture in deep recession. ... Standing here he may reflect upon the way in which a scene so classical, so deliberate, so complete, has been accomplished not by the decisions of one mind at one time but by a combination of accident, selection, genius and the tides of taste.

As of 2012, the current earl, William Herbert, 18th Earl of Pembroke, and his family live in the house.[25][26] In 2006, Herbert told The New York Times Magazine that the Wilton estate has around 140 employees. Its 14,000 acres are divided into 14 farms, one of which is run by the estate (the others are rented to tenants) and more than 200 residential properties. Although the house is open to the public, Herbert and his wife occupy about a third of the house privately.[27] Salisbury Racecourse and South Wilts Golf Course are also on the 14,000 acre estate.

In film and television

[edit]The house has been used for filming, including: Romance with a Double Bass (1974);[28] Barry Lyndon (1975);[28] The Music Lovers;[28] The Bounty (1984);[28] Treasure Houses of Britain (1985);[29] Blackadder II;[28] The Madness of King George (1994);[28] Of Mirrors, Paintings and Windows: Spectatorship in Ang Lee’s Sense and Sensibility (1995);[28] Mrs Brown (1997);[28] Pride & Prejudice (2005);[30][28] The Young Victoria (2009);[28] Outlander (2014);[28] The Crown (2016);[28] Tomb Raider (2018);[31][28] Emma (2020);[28] Bridgerton (2020);[32][28] and The Diplomat (2024).[33]

References

[edit]- ^ "Shakespeare's men perform before the King at Wilton in Salisbury". BBC. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ F. E. Halliday (1964). A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964, Baltimore: Penguin, p. 531.

- ^ Evans, Barbara (23 March 2021). "Mary Sidney Herbert". Her Salisbury Story. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- ^ Susan James. Catherine Parr: Henry VIII's Last Love, The History Press, 2009.

- ^ Katherine Parr, editor Janel Mueller. Katherine Parr: Complete Works and Correspondence, University of Chicago Press, 30 June 2011. pg 6.

- ^ Sir Nevile Rodwell Wilkinson. Wilton House Guide: A Handbook for Visitors, Chiswick Press, 1908. pg 80.

- ^ Anthony Nicolson. Quarrel with the King: The Story of an English Family on the High Road to Civil War, Harper Collins, 3 November 2009. pg 63-4.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Wilton House (1023762)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Brief Lives', chiefly of Contemporaries, set down by John Aubrey, between the Years 1669 & 1696; edited by Andrew Clark, p. 316, Volume I A-H at the Internet Archive

- ^ Historic England. "Holbein Porch (1199912)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ Horatio Brown, Calendar State Papers, Venice: 1603-1607, vol. 10 (London, 1900), p. 116 no. 164.

- ^ Peter Cunningham, Extracts from the Revels at Court (London, 1842), p. xxxiv.

- ^ Tresham Lever, Herberts of Wilton (London, 1967), p. 77.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Triumphal entrance arch and flanking lodges (1365920)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Washern Grange (1023764)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ Washern in the Domesday Book

- ^ Crittall, Elizabeth, ed. (1962). "The borough of Wilton: Introduction". A History of the County of Wiltshire, Volume 6. University of London. pp. 1–7. Retrieved 29 January 2021 – via British History Online.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Palladian Bridge (1023763)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ "Marble Bridge". Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ Edward Thomas Stevens, Jottings on some of the objects of interest in the Stonehenge excursion (1882), p. 158

- ^ Historic England. "Wilton: parks and gardens (1000440)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ "History", Wilton House, accessed 24 May 2012 Archived 11 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Visitor Information". Wilton House. Archived from the original on 7 March 2019.

- ^ "Untitled document" (PDF). Verity Lodge No. 59, Kent, Washington. p. 18. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Herbert, William. "Welcome to Wilton House" Archived 11 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Wilton House, accessed 24 May 2012

- ^ Blake, Morwenna. "Baby girl for Lord and Lady Pembroke", Salisbury Journal, 5 April 2011, accessed 24 May 2012

- ^ Lewine, Edward. "Lord of the Manor", The New York Times Magazine, 19 November 2006

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Filming". Wilton House. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ "Press release" (PDF). National Gallery of Art. WETA-TV. 1985. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Pride & Prejudice: The Locations". Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ Filming locations at the Internet Movie Database

- ^ "On Location: How Netflix Created the Grand British Estates of 'Bridgerton'". Conde Nast Traveler. 25 December 2020.

- ^ Hatchett, Keisha (2 November 2024). "Where is The Diplomat Filmed? Your Guide to the Season 2 Locations". Netflix. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Bold, John, Wilton House and English Palladianism. London, HMSO. 1988. ISBN 0-11-300022-7

- Colvin, Howard, A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Wilton House at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wilton House at Wikimedia Commons