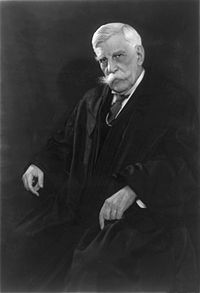

Clear and present danger was a doctrine adopted by the Supreme Court of the United States to determine under what circumstances limits can be placed on First Amendment freedoms of speech, press, or assembly. Created by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. to refine the bad tendency test, it was never fully adopted and both tests were ultimately replaced in 1969 with Brandenburg v. Ohio's "imminent lawless action" test.

History

[edit]Before the 20th century, most restrictions on free speech issues in the United States were imposed to prevent certain types of speech. Although certain kinds of speech continue to be prohibited in advance,[1] dangerous speech started to be punished after the fact in the early 1900s, at a time when US courts primarily relied on a doctrine known as the bad tendency test.[2] Rooted in English common law, the test permitted speech to be outlawed if it had a tendency to harm public welfare.[2]

Antiwar protests during World War I gave rise to several important free speech cases related to sedition and inciting violence. In the 1919 case Schenck v. United States, the Supreme Court held that an antiwar activist did not have a First Amendment right to advocate draft resistance.[3][4] In his majority opinion, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. introduced the clear and present danger test, which would become an important concept in First Amendment law

The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that the United States Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree. When a nation is at war, many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right.

In Frohwerk v. United States (1919) Justice Holmes summarized comments critical of U.S. wartime policies written by a newspaperman and stated about these comments the following: "It may be that all this might be said or written even in time of war in circumstances that would not make it a crime. We do not lose our right to condemn either measures or men because the country is at war."[5] This statement "represents an important addendum to the original explication of the clear and present danger test in that it specifies that even during war, courts should regard criticism of government policies and officials as protected speech."[5]

The Schenck decision did not formally adopt the clear and present danger test.[3] Holmes later wrote that he intended the clear and present danger test to refine, not replace, the bad tendency test.[6][7] Although sometimes mentioned in subsequent rulings, the clear and present danger test was never endorsed by the Supreme Court as a test to be used by lower courts when evaluating the constitutionality of legislation that regulated speech.[8][9]

The Court continued to use the bad tendency test during the early 20th century in cases such as 1919's Abrams v. United States, which upheld the conviction of antiwar activists who passed out leaflets encouraging workers to impede the war effort.[10] In Abrams, Holmes and Justice Brandeis dissented and encouraged the use of the clear and present test, which provided more protection for speech.[11] In 1925's Gitlow v. New York, the Court made the First Amendment applicable against the states and upheld the conviction of Gitlow for publishing the "Left wing manifesto".[12] Gitlow was decided based on the bad tendency test, but the majority decision acknowledged the validity of the clear and present danger test, yet concluded that its use was limited to Schenck-like situations where the speech was not specifically outlawed by the legislature.[6][13]

Brandeis and Holmes again promoted the clear and present danger test, this time in a concurring opinion in 1927's Whitney v. California decision.[6][14] The majority did not adopt or use the clear and present danger test, but the concurring opinion encouraged the Court to support greater protections for speech, and it suggested that "imminent danger" – a more restrictive wording than "present danger" – should be required before speech can be outlawed.[15] After Whitney, the bad tendency test continued to be used by the Court in cases such as Stromberg v. California, which held that a 1919 California statute banning red flags was unconstitutional.[16]

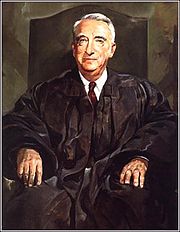

The clear and present danger test was invoked by the majority in the 1940 Thornhill v. Alabama decision in which a state anti-picketing law was invalidated.[8][17] Although the Court referred to the clear and present danger test in a few decisions following Thornhill,[18][19] the bad tendency test was not explicitly overruled,[8] and the clear and present danger test was not applied in several subsequent free speech cases involving incitement to violence.[20] The importance of freedom of speech in the context of "clear and present danger" was emphasized in Terminiello v. City of Chicago (1949),[21] in which the Supreme Court noted that the vitality of civil and political institutions in society depends on free discussion.[22] Democracy requires free speech because it is only through free debate and free exchange of ideas that government remains responsive to the will of the people and peaceful change is effected.[22] Restrictions on free speech are permissible only when the speech at issue is likely to produce a clear and present danger of a serious substantive evil that rises far above public inconvenience, annoyance, or unrest.[22] Justice William O. Douglas wrote for the Court that "a function of free speech under our system is to invite dispute. It may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger."[22]

Dennis v. United States

[edit]

In May 1950, one month before the appeals court heard oral arguments in the Dennis v. United States case, the Supreme Court ruled on free speech issues in American Communications Association v. Douds. In that case, the Court considered the clear and present danger test, but rejected it as too mechanical and instead introduced a balancing test.[23] The federal appeals court heard oral arguments in the CPUSA case on June 21–23, 1950. Judge Learned Hand considered the clear and present danger test, but his opinion adopted a balancing approach similar to that suggested in American Communications Association v. Douds.[6][24]

The defendants appealed the Second Circuit's decision to the Supreme Court in Dennis v. United States. The 6–2 decision was issued on June 4, 1951, and upheld Hand's decision. Chief Justice Fred Vinson's opinion stated that the First Amendment does not require that the government must wait "until the putsch is about to be executed, the plans have been laid and the signal is awaited" before it interrupts seditious plots.[25] In his opinion, Vinson endorsed the balancing approach used by Judge Hand:[26][27][28]

Chief Judge Learned Hand ... interpreted the [clear and present danger] phrase as follows: 'In each case, [courts] must ask whether the gravity of the "evil", discounted by its improbability, justifies such invasion of free speech as is necessary to avoid the danger.' We adopt this statement of the rule. As articulated by Chief Judge Hand, it is as succinct and inclusive as any other we might devise at this time. It takes into consideration those factors which we deem relevant, and relates their significances. More we cannot expect from words.

Importance

[edit]Following Schenck v. United States, "clear and present danger" became both a public metaphor for First Amendment speech[29][30] and a standard test in cases before the Court where a United States law limits a citizen's First Amendment rights; the law is deemed to be constitutional if it can be shown that the language it prohibits poses a "clear and present danger". However, the "clear and present danger" criterion of the Schenck decision was replaced in 1969 by Brandenburg v. Ohio,[31] and the test refined to determining whether the speech would provoke an "imminent lawless action".

The vast majority[who?] of legal scholars have concluded that in writing the Schenck opinion, Justice Holmes never meant to replace the "bad tendency" test which had been established in the 1868 English case R. v. Hicklin and incorporated into American jurisprudence in the 1904 Supreme Court case U.S. ex rel. Turner v. Williams.[32] This is demonstrated by the use of the word "tendency" in Schenck itself, a paragraph in Schenck explaining that the success of speech in causing the actual harm was not a prerequisite for conviction, and use of the bad-tendency test in the simultaneous Frohwerk v. United States and Debs v. United States decisions (both of which cite Schenck without using the words "clear and present danger").

However, a subsequent essay by Zechariah Chafee titled "Freedom of Speech in War Time" argued despite context that Holmes had intended to substitute clear and present danger for the bad-tendency standard a more protective standard of free speech.[33] Bad tendency was a far more ambiguous standard where speech could be punished even in the absence of identifiable danger, and as such was strongly opposed by the fledgling American Civil Liberties Union and other libertarians of the time.

Having read Chafee's article, Holmes decided to retroactively reinterpret what he had meant by "clear and present danger" and accepted Chafee's characterization of the new test in his dissent in Abrams v. United States just six months after Schenck.[34] Schenck, Frohwerk, and Debs all resulted in unanimous decisions, while Abrams did not.

Brandenburg

[edit]For two decades after the Dennis decision, free speech issues related to advocacy of violence were decided using balancing tests such as the one initially articulated in Dennis.[35] In 1969, the court established stronger protections for speech in the landmark case Brandenburg v. Ohio, which held that "the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action".[36][37] Brandenburg is now the standard applied by the Court to free speech issues related to advocacy of violence.[38]

See also

[edit]- Imminent lawless action

- List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 395

- Shouting fire in a crowded theater

- Threatening the president of the United States

- Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919)

- Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969)

- Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568 (1942)

- Dennis v. United States, 341 U.S. 494 (1951)

- Feiner v. New York, 340 U.S. 315 (1951)

- Hess v. Indiana, 414 U.S. 105 (1973)

- Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944)

- Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten, (1917)

- Sacher v. United States, 343 U.S. 1 (1952)

- Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919)

- Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949)

- Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. 357 (1927)

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Prior Restraint". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

- ^ a b Rabban, pp 132–134, 190–199.

- ^ a b Killian, p 1093.

- ^ Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919).

- ^ a b Parker, Richard (December 15, 2023). "Frohwerk v. United States(1919)". Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University. Archived from the original on February 2, 2024. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Dunlap, William V., "National Security and Freedom of Speech", in Finkelman (vol 1), pp 1072–1074.

- ^ Rabban, pp 285–286.

- ^ a b c Killian, pp 1096, 1100.

Currie, David P., The Constitution in the Supreme Court: The Second Century, 1888–1986, University of Chicago Press, 1994, p 269, ISBN 9780226131122.

Konvitz, Milton Ridvad, Fundamental Liberties of a Free People: Religion, Speech, Press, Assembly, Transaction Publishers, 2003, p 304, ISBN 9780765809544.

Eastland, p 47. - ^ The Court adopted the imminent lawless action test in Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969), which some commentators view as a modified version of the clear and present danger test.

- ^ Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919).

The bad tendency test was also used in Frohwerk v. United States, 249 U.S. 204 (1919); Debs v. United States, 249 U.S. 211 (1919); and Schaefer v. United States, 251 U.S. 466 (1920).

See Rabban, David, "Clear and Present Danger Test", in The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States, p 183, 2005, ISBN 9780195176612 . - ^ Killian, p. 1094.

Rabban, p 346.

Redish, p 102. - ^ Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652 (1925).

- ^ Redish, p 102.

Kemper, p 653. - ^ Whitney v. California 274 U.S. 357 (1927).

- ^ Redish pp 102–104.

Killian, p 1095. - ^ Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 359 (1931).

Killian, p 1096.

Another case from that era that used the bad tendency test was Fiske v. Kansas, 274 U.S. 380 (1927). - ^ Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 (1940).

- ^ Including Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 (1940): "When clear and present danger of riot, disorder, interference with traffic upon the public streets, or other immediate threat to public safety, peace, or order appears, the power of the State to prevent or punish is obvious.... [W]e think that, in the absence of a statute narrowly drawn to define and punish specific conduct as constituting a clear and present danger to a substantial interest of the State, the petitioner's communication, considered in the light of the constitutional guarantees, raised no such clear and present menace to public peace and order as to render him liable to conviction of the common law offense in question."

- ^ And Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252 (1941): "And, very recently [in Thornhill] we have also suggested that 'clear and present danger' is an appropriate guide in determining the constitutionality of restrictions upon expression.... What finally emerges from the 'clear and present danger' cases is a working principle that the substantive evil must be extremely serious, and the degree of imminence extremely high, before utterances can be punished."

- ^ Antieu, Chester James, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, Wm. S. Hein Publishing, 1998, p 219, ISBN 9781575884431. Antieu names Feiner v. New York, 340 U.S. 315 (1951); Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire 315 U.S. 568 (1942); and Kovacs v. Cooper, 335 U.S. 77 (1949).

- ^ Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949)

- ^ a b c d Terminiello, at 4

- ^ Eastland, p 47.

Killian, p 1101.

American Communications Association v. Douds 339 U.S. 382 (1950). - ^ Eastland, pp 96, 112–113.

Sabin, p 79.

O'Brien, pp 7–8.

Belknap (1994), p 222.

Walker, p 187.

Belknap, Michal, The Vinson Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy, ABC-CLIO, 2004, p 109, ISBN 9781576072011.

Kemper, p 655. - ^ Belknap (1994), p 223. Vinson quoted by Belknap.

- ^ Dennis v. United States - 341 U.S. 494 (1951) Justia. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- ^ Killian, p 1100.

Kemper, pp 654–655. - ^ Steiner, Ronald (September 19, 2023). "Gravity of the Evil Test". Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University. Archived from the original on February 2, 2024. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ Derrick, Geoffrey J. (2007). "Why the Judiciary Should Protect First Amendment Political Speech During Wartime: The Case for Deliberative Democracy". Lethbridge Undergraduate Research Journal. 2 (1). ISSN 1718-8482. Archived from the original on 2008-04-22.

- ^ Tsai, Robert L. (2004). "Fire, Metaphor, and Constitutional Myth-Making". Georgetown Law Journal. 93: 181–239. ISSN 0016-8092.

- ^ Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969).

- ^ "FindLaw's United States Supreme Court case and opinions".

- ^ Chafee, Zechariah (1919). "Freedom of Speech in Wartime". Harvard Law Review. 32 (8): 932–973. doi:10.2307/1327107. JSTOR 1327107.

- ^ Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919).

- ^ Including cases such as Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 366 U.S. 36 (1961).

Killian, pp 1101–1103. - ^ Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969).

- ^ Redish pp 104–106.

Killian, pp 1109–1110. - ^ E.g. in cases such as Hess v. Indiana, 414 U.S. 105 (1973).

Redish, p 105.

Kemper, p 653.

References

[edit]- Eastland, Terry, Freedom of Expression in the Supreme Court: The Defining Cases, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 16. August 2000, ISBN 978-0847697113

- Finkelman, Paul (Editor), Encyclopedia of American Civil Liberties (two volumes), CRC Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0415943420

- Kemper, Mark, "Freedom of Speech", in Finkelman, Vol 1, p 653–655.

- Killian, Johnny H.; Costello, George; Thomas, Kenneth R., The Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis and Interpretation, Library of Congress, Government Printing Office, 2005, ISBN 978-0160723797 [1]

- Rabban, David, Free Speech in Its Forgotten Years, Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0521655378

- Redish, Martin H., The Logic of Persecution: Free Expression and the McCarthy Era, Stanford University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0804755931

Further reading

[edit]- Chester James Antieau, "The Rule of Clear and Present Danger: Scope of Its Applicability," Michigan Law Review, vol. 48, no. 6 (April 1950), pp. 811–840. In JSTOR

- Louis B. Boudin, "'Seditious Doctrines' and the 'Clear and Present Danger' Rule: Part I," Virginia Law Review, vol. 38, no. 2 (Feb. 1952), pp. 143–186. In JSTOR

- Louis B. Boudin, "'Seditious Doctrines' and the 'Clear and Present Danger' Rule: Part II," Virginia Law Review, vol. 38, no. 3 (April 1952), pp. 315–356. In JSTOR

- Mark Kessler, "Legal Discourse and Political Intolerance: The Ideology of Clear and Present Danger," Law & Society Review, vol. 27, no. 3 (1993), pp. 559–598. In JSTOR

- Fred D. Ragan, "Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Zechariah Chafee, Jr., and the Clear and Present Danger Test for Free Speech: The First Year, 1919," Journal of American History, vol. 58, no. 1 (1971), pp. 24–45. In JSTOR

- Bernard Schwartz, "Holmes versus Hand: Clear and Present Danger or Advocacy of Unlawful Action?" Supreme Court Review," vol. 1994, pp. 209–245. In JSTOR

External links

[edit]- First Amendment Library entry on Schenck v. United States

- First Amendment Library entry on Famous First Amendment Phrases: Origins

- ^ "Browse | Constitution Annotated | Congress.gov | Library of Congress". Constitution.congress.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-03.