| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Butan-1-ol[1] | |||

| Other names

n-Butanol

n-Butyl alcohol n-Butyl hydroxide n-Propylcarbinol n-Propylmethanol 1-Hydroxybutane Methylolpropane | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 969148 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.683 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 25753 | |||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | 1-Butanol | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1120 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C4H10O | |||

| Molar mass | 74.123 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colourless, refractive liquid | ||

| Odor | banana-like,[2] harsh, alcoholic and sweet | ||

| Density | 0.81 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | −89.8 °C (−129.6 °F; 183.3 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 117.7 °C (243.9 °F; 390.8 K) | ||

| 73 g/L at 25 °C | |||

| Solubility | very soluble in acetone miscible with ethanol, ethyl ether | ||

| log P | 0.839 | ||

| Vapor pressure | 0.58 kPa (20 °C) ILO International Chemical Safety Cards (ICSC) | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 16.10 | ||

| −56.536·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.3993 (20 °C) | ||

| Viscosity | 2.573 mPa·s (at 25 °C) [3] | ||

| 1.66 D | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

225.7 J/(K·mol) | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−328(4) kJ/mol | ||

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−2670(20) kJ/mol | ||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 35 °C (95 °F; 308 K) | ||

| 343 °C (649 °F; 616 K) | |||

| Explosive limits | 1.45–11.25% | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

790 mg/kg (rat, oral) | ||

LDLo (lowest published)

|

3484 mg/kg (rabbit, oral) 790 mg/kg (rat, oral) 1700 mg/kg (dog, oral)[5] | ||

LC50 (median concentration)

|

9221 ppm (mammal) 8000 ppm (rat, 4 h)[5] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 100 ppm (300 mg/m3)[4] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

C 50 ppm (150 mg/m3) [skin][4] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

1400 ppm[4] | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 0111 | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related compounds

|

Butanethiol n-Butylamine Diethyl ether Pentane | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

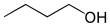

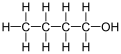

1-Butanol, also known as butan-1-ol or n-butanol, is a primary alcohol with the chemical formula C4H9OH and a linear structure. Isomers of 1-butanol are isobutanol, butan-2-ol and tert-butanol. The unmodified term butanol usually refers to the straight chain isomer.

1-Butanol occurs naturally as a minor product of the ethanol fermentation of sugars and other saccharides[6] and is present in many foods and drinks.[7][8] It is also a permitted artificial flavorant in the United States,[9] used in butter, cream, fruit, rum, whiskey, ice cream and ices, candy, baked goods, and cordials.[10] It is also used in a wide range of consumer products.[7]

The largest use of 1-butanol is as an industrial intermediate, particularly for the manufacture of butyl acetate (itself an artificial flavorant and industrial solvent). It is a petrochemical derived from propylene. Estimated production figures for 1997 are: United States 784,000 tonnes; Western Europe 575,000 tonnes; Japan 225,000 tonnes.[8]

Production

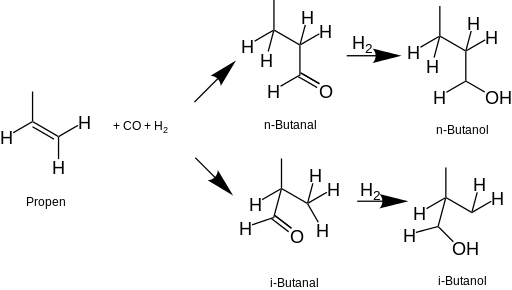

[edit]Since the 1950s, most 1-butanol is produced by the hydroformylation of propene (oxo process) to preferentially form the butyraldehyde n-butanal. Typical catalysts are based on cobalt and rhodium. Butyraldehyde is then hydrogenated to produce butanol.

A second method for producing butanol involves the Reppe reaction of propylene with CO and water:[11]

- CH3CH=CH2 + H2O + 2 CO → CH3CH2CH2CH2OH + CO2

In former times, butanol was prepared from crotonaldehyde, which can be obtained from acetaldehyde.

Butanol can also be produced by fermentation of biomass by bacteria. Prior to the 1950s, Clostridium acetobutylicum was used in industrial fermentation to produce butanol. Research in the past few decades showed results of other microorganisms that can produce butanol through fermentation.

Butanol can be produced via furan hydrogenation over Pd or Pt catalyst at high temperature and high pressure.https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2014/gc/c3gc41183d

Industrial use

[edit]Constituting 85% of its use, 1-butanol is mainly used in the production of varnishes. It is a popular solvent, e.g. for nitrocellulose. A variety of butanol derivatives are used as solvents, e.g. butoxyethanol or butyl acetate. Many plasticizers are based on butyl esters, e.g., dibutyl phthalate. The monomer butyl acrylate is used to produce polymers. It is the precursor to n-butylamines.[11]

Biofuel

[edit]1-Butanol has been proposed as a substitute for diesel fuel and gasoline. It is produced in small quantities in nearly all fermentations (see fusel oil). Clostridium produces much higher yields of butanol. Research is underway to increase the biobutanol yield from biomass.

Butanol is considered as a potential biofuel (butanol fuel). Butanol at 85 percent strength can be used in cars designed for gasoline without any change to the engine (unlike 85% ethanol), and it provides more energy for a given volume than ethanol, almost as much as gasoline. Therefore, a vehicle using butanol would return fuel consumption more comparable to gasoline than ethanol. Butanol can also be added to diesel fuel to reduce soot emissions.[12]

The production of, or in some cases, the use of, the following substances may result in exposure to 1-butanol: artificial leather, butyl esters, rubber cement, dyes, fruit essences, lacquers, motion picture, and photographic films, raincoats, perfumes, pyroxylin plastics, rayon, safety glass, shellac varnish, and waterproofed cloth.[7]

Occurrence in nature

[edit]Butan-1-ol occurs naturally as a result of carbohydrate fermentation in a number of alcoholic beverages, including beer,[13] grape brandies,[14] wine,[15] and whisky.[16] It has been detected in the volatiles of hops,[17] jack fruit,[18] heat-treated milks,[19] musk melon,[20] cheese,[21] southern pea seed,[22] and cooked rice.[23] 1-Butanol is also formed during deep frying of corn oil, cottonseed oil, trilinolein, and triolein.[24]

Butan-1-ol is one of the "fusel alcohols" (from the German for "bad liquor"), which include alcohols that have more than two carbon atoms and have significant solubility in water.[25] It is a natural component of many alcoholic beverages, albeit in low and variable concentrations.[26][27] It (along with similar fusel alcohols) is reputed to be responsible for severe hangovers, although experiments in animal models show no evidence for this.[28]

1-Butanol is used as an ingredient in processed and artificial flavorings,[29] and for the extraction of lipid-free protein from egg yolk,[30] natural flavouring materials and vegetable oils, the manufacture of hop extract for beermaking, and as a solvent in removing pigments from moist curd leaf protein concentrate.[31]

Metabolism and toxicity

[edit]The acute toxicity of 1-butanol is relatively low, with oral LD50 values of 790–4,360 mg/kg (rat; comparable values for ethanol are 7,000–15,000 mg/kg).[8][32][11] It is metabolized completely in vertebrates in a manner similar to ethanol: alcohol dehydrogenase converts 1-butanol to butyraldehyde; this is then converted to butyric acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase. Butyric acid can be fully metabolized to carbon dioxide and water by the β-oxidation pathway. In the rat, only 0.03% of an oral dose of 2,000 mg/kg was excreted in the urine.[33] At sub-lethal doses, 1-butanol acts as a depressant of the central nervous system, similar to ethanol: one study in rats indicated that the intoxicating potency of 1-butanol is about 6 times higher than that of ethanol, possibly because of its slower transformation by alcohol dehydrogenase.[34]

Other hazards

[edit]Liquid 1-butanol, as is common with most organic solvents, is extremely irritating to the eyes; repeated contact with the skin can also cause irritation.[8] This is believed to be a generic effect of defatting. No skin sensitization has been observed. Irritation of the respiratory pathways occurs only at very high concentrations (>2,400 ppm).[35]

With a flash point of 35 °C, 1-butanol presents a moderate fire hazard: it is slightly more flammable than kerosene or diesel fuel but less flammable than many other common organic solvents. The depressant effect on the central nervous system (similar to ethanol intoxication) is a potential hazard when working with 1-butanol in enclosed spaces, although the odour threshold (0.2–30 ppm) is far below the concentration which would have any neurological effect.[35][36]

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- International Chemical Safety Card 0111

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0076". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- SIDS Initial Assessment Report for n-Butanol from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

- IPCS Environmental Health Criteria 65: Butanols: four isomers

- IPCS Health and Safety Guide 3: 1-Butanol

References

[edit]- ^ "1-Butanol - Compound Summary". The PubChem Project. USA: National Center of Biotechnology Information.

- ^ [n-Butanol Product Information, The Dow Chemical Company, Form No. 327-00014-1001, page 1]

- ^ Dubey, Gyan (2008). "Study of densities, viscosities, and speeds of sound of binary liquid mixtures of butan-1-ol with n-alkanes (C6, C8, and C10) at T = (298.15, 303.15, and 308.15) K". The Journal of Chemical Thermodynamics. 40 (2): 309–320. doi:10.1016/j.jct.2007.05.016.

- ^ a b c NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0076". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b "N-butyl alcohol". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Hazelwood, Lucie A.; Daran, Jean-Marc; van Maris, Antonius J. A.; Pronk, Jack T.; Dickinson, J. Richard (2008), "The Ehrlich pathway for fusel alcohol production: a century of research on Saccharomyces cerevisiae metabolism", Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 74 (8): 2259–66, Bibcode:2008ApEnM..74.2259H, doi:10.1128/AEM.02625-07, PMC 2293160, PMID 18281432.

- ^ a b c Butanols: four isomers, Environmental Health Criteria monograph No. 65, Geneva: World Health Organization, 1987, ISBN 92-4-154265-9.

- ^ a b c d n-Butanol (PDF), SIDS Initial Assessment Report, Geneva: United Nations Environment Programme, April 2005.

- ^ 21 C.F.R. § 172.515; 42 FR 14491, Mar. 15, 1977, as amended.

- ^ Hall, R. L.; Oser, B. L. (1965), "Recent progress in the consideration of flavouring ingredients under the food additives amendment. III. Gras substances", Food Technol.: 151, cited in Butanols: four isomers, Environmental Health Criteria monograph No. 65, Geneva: World Health Organization, 1987, ISBN 92-4-154265-9.

- ^ a b c Hahn, Heinz-Dieter; Dämbkes, Georg; Rupprich, Norbert (2005). "Butanols". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a04_463. ISBN 978-3527306732..

- ^ Antoni, D.; Zverlov, V. & Schwarz, W. H. (2007). "Biofuels from Microbes". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 77 (1): 23–35. doi:10.1007/s00253-007-1163-x. PMID 17891391. S2CID 35454212.

- ^ Bonte, W. (1979), "Congener substances in German and foreign beers", Blutalkohol, 16: 108–24, cited in Butanols: four isomers, Environmental Health Criteria monograph No. 65, Geneva: World Health Organization, 1987, ISBN 92-4-154265-9.

- ^ Schreier, Peter; Drawert, Friedrich; Winkler, Friedrich (1979), "Composition of neutral volatile constituents in grape brandies", J. Agric. Food Chem., 27 (2): 365–72, doi:10.1021/jf60222a031.

- ^ Bonte, W. (1978), "Congener content of wine and similar beverages", Blutalkohol, 15: 392–404, cited in Butanols: four isomers, Environmental Health Criteria monograph No. 65, Geneva: World Health Organization, 1987, ISBN 92-4-154265-9.

- ^ Postel, W.; Adam, L. (1978), "Gas chromatographic characterization of whiskey. III. Irish whiskey", Branntweinwirtschaft, 118: 404–7, cited in Butanols: four isomers, Environmental Health Criteria monograph No. 65, Geneva: World Health Organization, 1987, ISBN 92-4-154265-9.

- ^ Tressl, Roland; Friese, Lothar; Fendesack, Friedrich; Koeppler, Hans (1978), "Studies of the volatile composition of hops during storage", J. Agric. Food Chem., 26 (6): 1426–30, doi:10.1021/jf60220a036.

- ^ Swords, G.; Bobbio, P. A.; Hunter, G. L. K. (1978), "Volatile constituents of jack fruit (Arthocarpus heterophyllus)", J. Food Sci., 43 (2): 639–40, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1978.tb02375.x.

- ^ Jaddou, Haytham A.; Pavey, John A.; Manning, Donald J. (1978), "Chemical analysis of flavor volatiles in heat-treated milks", J. Dairy Res., 45 (3): 391–403, doi:10.1017/S0022029900016617, S2CID 85985458.

- ^ Yabumoto, K.; Yamaguchi, M.; Jennings, W. G. (1978), "Production of volatile compounds by Muskmelon, Cucumis melo", Food Chem., 3 (1): 7–16, doi:10.1016/0308-8146(78)90042-0.

- ^ Dumont, Jean Pierre; Adda, Jacques (1978), "Occurrence of sesquiterpones in mountain cheese volatiles", J. Agric. Food Chem., 26 (2): 364–67, doi:10.1021/jf60216a037.

- ^ Fisher, Gordon S.; Legendre, Michael G.; Lovgren, Norman V.; Schuller, Walter H.; Wells, John A. (1979), "Volatile constituents of southernpea seed [Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.]", J. Agric. Food Chem., 27 (1): 7–11, doi:10.1021/jf60221a040.

- ^ Yajima, Izumi; Yanai, Tetsuya; Nakamura, Mikio; Sakakibara, Hidemasa; Habu, Tsutomu (1978), "Volatile flavor components of cooked rice", Agric. Biol. Chem., 42 (6): 1229–33, doi:10.1271/bbb1961.42.1229.

- ^ Chang, S. S.; Peterson, K. J.; Ho, C. (1978), "Chemical reactions involved in the deep-fat frying of foods", J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc., 55 (10): 718–27, doi:10.1007/BF02665369, PMID 730972, S2CID 97273264, cited in Butanols: four isomers, Environmental Health Criteria monograph No. 65, Geneva: World Health Organization, 1987, ISBN 92-4-154265-9.

- ^ Atsumi, S.; Hanai, T.; Liao, J. C. (2008). "Non-fermentative pathways for synthesis of branched-chain higher alcohols as biofuels". Nature. 451 (7174): 86–89. Bibcode:2008Natur.451...86A. doi:10.1038/nature06450. PMID 18172501. S2CID 4413113.

- ^ Woo, Kang-Lyung (2005), "Determination of low molecular weight alcohols including fusel oil in various samples by diethyl ether extraction and capillary gas chromatography", J. AOAC Int., 88 (5): 1419–27, doi:10.1093/jaoac/88.5.1419, PMID 16385992.

- ^ Lachenmeier, Dirk W.; Haupt, Simone; Schulz, Katja (2008), "Defining maximum levels of higher alcohols in alcoholic beverages and surrogate alcohol products", Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 50 (3): 313–21, doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.12.008, PMID 18295386.

- ^ Hori, Hisako; Fujii, Wataru; Hatanaka, Yutaka; Suwa, Yoshihide (2003), "Effects of fusel oil on animal hangover models", Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res., 27 (8 Suppl): 37S – 41S, doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000078828.49740.48, PMID 12960505.

- ^ Mellan, I. (1950), Industrial Solvents, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, pp. 482–88, cited in Butanols: four isomers, Environmental Health Criteria monograph No. 65, Geneva: World Health Organization, 1987, ISBN 92-4-154265-9.

- ^ Meslar, Harry W.; White, Harold B. III (1978), "Preparation of lipid-free protein extracts of egg yolk", Anal. Biochem., 91 (1): 75–81, doi:10.1016/0003-2697(78)90817-5, PMID 9762085.

- ^ Bray, Walter J.; Humphries, Catherine (1978), "Solvent fractionation of leaf juice to prepare green and white protein products", J. Sci. Food Agric., 29 (10): 839–46, Bibcode:1978JSFA...29..839B, doi:10.1002/jsfa.2740291003.

- ^ Ethanol (PDF), SIDS Initial Assessment Report, Geneva: United Nations Environment Programme, August 2005.

- ^ Gaillard, D.; Derache, R. (1965), "Métabilisation de différents alcools présents dans les biossons alcooliques chez le rat", Trav. Soc. Pharmacol. Montpellier, 25: 541–62, cited in Butanols: four isomers, Environmental Health Criteria monograph No. 65, Geneva: World Health Organization, 1987, ISBN 92-4-154265-9.

- ^ McCreery, N. J.; Hunt, W. A. (1978), "Physico-chemical correlates of alcohol intoxication", Neuropharmacology, 17 (7): 451–61, doi:10.1016/0028-3908(78)90050-3, PMID 567755, S2CID 19914287.

- ^ a b Wysocki, C. J.; Dalton, P. (1996), Odor and Irritation Thresholds for 1-Butanol in Humans, Philadelphia: Monell Chemical Senses Center, cited in n-Butanol (PDF), SIDS Initial Assessment Report, Geneva: United Nations Environment Programme, April 2005.

- ^ Cometto-Muñiz, J. Enrique; Cain, William S. (1998), "Trigeminal and Olfactory Sensitivity: Comparison of Modalities and Methods of Measurement", Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health, 71 (2): 105–10, Bibcode:1998IAOEH..71..105C, doi:10.1007/s004200050256, PMID 9580447, S2CID 25246408.