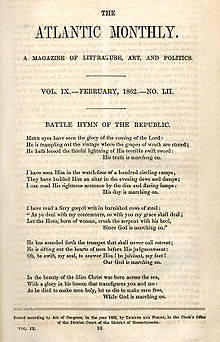

Cover of the 1863 sheet music for the "Battle Hymn of the Republic" | |

| Lyrics | Julia Ward Howe, 1861 |

|---|---|

| Music | William Steffe, 1856; arranged by James E. Greenleaf, C. S. Hall, and C. B. Marsh, 1861 |

| Audio sample | |

"The Battle Hymn of the Republic" as performed by the United States Air Force Band | |

The "Battle Hymn of the Republic" is an American patriotic song written by the abolitionist writer Julia Ward Howe during the American Civil War.

Howe adapted her song from the soldiers' song "John Brown's Body" in November 1861, and sold it for $4 to The Atlantic Monthly[1] in February 1862. In contrast to the lyrics of the soldiers’ song, her version links the Union cause with God's vengeance at the Day of Judgment (through allusions to biblical passages such as Isaiah 63:1–6, Revelation 19 and Revelation 14:14–19).

Julia Ward Howe was married to Samuel Gridley Howe, a scholar in education of the blind. Both Samuel and Julia were also active leaders in anti-slavery politics and strong supporters of the Union. Samuel was a member of the Secret Six, the group who funded John Brown's work.[2]

History

[edit]"Oh! Brothers"

[edit]The tune and some of the lyrics of "John Brown’s Body" came from a much older folk hymn called "Say, Brothers will you Meet Us", also known as "Glory Hallelujah", which has been developed in the oral hymn tradition of revivalist camp meetings of the late 1700s, though it was first published in the early 1800s. In the first known version, "Canaan's Happy Shore", the text includes the verse "Oh! Brothers will you meet me (3×)/On Canaan's happy shore?"[3]: 21 and chorus "There we'll shout and give Him glory (3×)/For glory is His own."[4] This developed into the familiar "Glory, glory, hallelujah" chorus by the 1850s. The tune and variants of these words spread across both the southern and northern United States.[5]

As the "John Brown's Body" song

[edit]At a flag-raising ceremony at Fort Warren, near Boston, Massachusetts, on Sunday, May 12, 1861, the song "John Brown's Body", using the "Oh! Brothers" tune and the "Glory, Hallelujah" chorus, was publicly played "perhaps for the first time".[citation needed] The American Civil War had begun the previous month.

In 1890, George Kimball wrote his account of how the 2nd Infantry Battalion of the Massachusetts militia, known as the "Tiger" Battalion, collectively worked out the lyrics to "John Brown's Body". Kimball wrote:

We had a jovial Scotchman in the battalion, named John Brown. ... [A]nd as he happened to bear the identical name of the old hero of Harper's Ferry, he became at once the butt of his comrades. If he made his appearance a few minutes late among the working squad, or was a little tardy in falling into the company line, he was sure to be greeted with such expressions as "Come, old fellow, you ought to be at it if you are going to help us free the slaves," or, "This can't be John Brown—why, John Brown is dead." And then some wag would add, in a solemn, drawling tone, as if it were his purpose to give particular emphasis to the fact that John Brown was really, actually dead: "Yes, yes, poor old John Brown is dead; his body lies mouldering in the grave."[6]

According to Kimball, these sayings became by-words among the soldiers and, in a communal effort—similar in many ways to the spontaneous composition of camp meeting songs described above—were gradually put to the tune of "Say, Brothers":

Finally ditties composed of the most nonsensical, doggerel rhymes, setting for the fact that John Brown was dead and that his body was undergoing the process of decomposition, began to be sung to the music of the hymn above given. These ditties underwent various ramifications, until eventually the lines were reached,—

"John Brown's body lies a-mouldering in the grave,

His soul's marching on."And,—

"He's gone to be a soldier in the army of the Lord,

His soul's marching on."These lines seemed to give general satisfaction, the idea that Brown's soul was "marching on" receiving recognition at once as having a germ of inspiration in it. They were sung over and over again with a great deal of gusto, the "Glory, hallelujah" chorus being always added.[6]

Some leaders of the battalion, feeling the words were coarse and irreverent, tried to urge the adoption of more fitting lyrics, but to no avail. The lyrics were soon prepared for publication by members of the battalion, together with publisher C. S. Hall. They selected and polished verses they felt appropriate, and may even have enlisted the services of a local poet to help polish and create verses.[7]

The official histories of the old First Artillery and of the 55th Artillery (1918) also record the Tiger Battalion's role in creating the John Brown Song, confirming the general thrust of Kimball's version with a few additional details.[8][9]

Creation of the "Battle Hymn"

[edit]

Kimball's battalion was dispatched to Murray, Kentucky, early in the Civil War, and Julia Ward Howe heard this song during a public review of the troops outside Washington, D.C., on Upton Hill, Virginia. Rufus R. Dawes, then in command of Company "K" of the 6th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry, stated in his memoirs that the man who started the singing was Sergeant John Ticknor of his company. Howe's companion at the review, the Reverend James Freeman Clarke,[10] suggested to Howe that she write new words for the fighting men's song. Staying at the Willard Hotel in Washington on the night of November 18, 1861, Howe wrote the verses to the "Battle Hymn of the Republic".[11] Of the writing of the lyrics, Howe remembered:

I went to bed that night as usual, and slept, according to my wont, quite soundly. I awoke in the gray of the morning twilight; and as I lay waiting for the dawn, the long lines of the desired poem began to twine themselves in my mind. Having thought out all the stanzas, I said to myself, "I must get up and write these verses down, lest I fall asleep again and forget them." So, with a sudden effort, I sprang out of bed, and found in the dimness an old stump of a pencil which I remembered to have used the day before. I scrawled the verses almost without looking at the paper.[12]

Howe's "Battle Hymn of the Republic" was first published on the front page of The Atlantic Monthly of February 1862. The sixth verse written by Howe, which is less commonly sung, was not published at that time.

The song was also published as a broadside in 1863 by the Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Regiments in Philadelphia.

Both "John Brown" and "Battle Hymn of the Republic" were published in Father Kemp's Old Folks Concert Tunes in 1874 and reprinted in 1889. Both songs had the same Chorus with an additional "Glory" in the second line: "Glory! Glory! Glory! Hallelujah!"[13]

Score

[edit]"Canaan's Happy Shore" has a verse and chorus of equal metrical length and both verse and chorus share an identical melody and rhythm. "John Brown's Body" has more syllables in its verse and uses a more rhythmically active variation of the "Canaan" melody to accommodate the additional words in the verse. In Howe's lyrics, the words of the verse are packed into a yet longer line, with even more syllables than "John Brown's Body." The verse still uses the same underlying melody as the refrain, but the addition of many dotted rhythms to the underlying melody allows for the more complex verse to fit the same melody as the comparatively short refrain.

- One version of the melody, in C major, begins as below. This is an example of the mediant-octave modal frame.

Lyrics

[edit]Howe submitted the lyrics she wrote to The Atlantic Monthly, and it was first published in the February 1862 issue of the magazine.[14][15]

First published version

[edit]Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord;

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword:

His truth is marching on.

(Chorus)

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

His truth is marching on.

I have seen Him in the watch-fires of a hundred circling camps,

They have builded Him an altar in the evening dews and damps;

I can read His righteous sentence by the dim and flaring lamps:

His day is marching on.

(Chorus)

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

His truth is marching on.

I have read a fiery gospel writ in burnished rows of steel:

"As ye deal with My contemners, so with you My grace shall deal";

Let the Hero, born of woman, crush the serpent with His heel,

Since God is marching on.

(Chorus)

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

His truth is marching on.

He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall never call retreat;

He is sifting out the hearts of men before His judgment-seat;

Oh, be swift, my soul, to answer Him! Be jubilant, my feet!

Our God is marching on.

(Chorus)

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Our God is marching on.

In the beauty of the lilies Christ was born across the sea,

With a glory in His bosom that transfigures you and me.

As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free,[16]

While God is marching on.

(Chorus)

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Our God is marching on.

* Some modern performances and recordings of the "Battle Hymn of the Republic" use the lyric "As He died to make men holy, let us live to make men free" as opposed to the wartime lyric originally written by Julia Ward Howe: "let us die to make men free."[17][18]

Other versions

[edit]Howe's original manuscript differed slightly from the published version. Most significantly, it included a final verse:

He is coming like the glory of the morning on the wave,

He is Wisdom to the mighty, He is Succour to the brave,

So the world shall be His footstool, and the soul of Time His slave,

Our God is marching on.

(Chorus)

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Our God is marching on!

In the 1862 sheet music, the chorus always begins:

Glory! Glory! Hallelujah!

Glory! Glory! Glory! Hallelujah!

Glory! Glory! Hallelujah!"[19]

Recordings and public performances

[edit]| "Battle Hymn of the Republic" | |

|---|---|

| Single by Mormon Tabernacle Choir | |

| B-side | "The Lord's Prayer" |

| Released | 1959 |

| Recorded | 1959 |

| Genre | Choral |

| Length | 3:07 |

| Label | Columbia |

| Songwriter(s) | Peter Wilhousky |

- In 1953, Marian Anderson sang the song before a television audience of 60 million persons, broadcast live over the NBC and CBS networks, as part of The Ford 50th Anniversary Show.

- In 1960 the Mormon Tabernacle Choir won the Grammy Award for Best Performance by a Vocal Group or Chorus. The 45 rpm single record, which was arranged and edited by Columbia Records and Cleveland disk jockey Bill Randle, was a commercial success and reached #13 on Billboard's Hot 100 the previous autumn. It is the choir's only Top 40 hit in the Hot 100.[20]

- Judy Garland performed this song on her weekly television show in December 1963. She originally wanted to do a dedication show for President John F. Kennedy upon his assassination, but CBS would not let her, so she performed the song without being able to mention his name.[21]

- Andy Williams experienced commercial success in 1968 with an a cappella version recorded at Senator Robert Kennedy's funeral. Backed by the St. Charles Borromeo choir, his version reached #11 on the adult contemporary chart and #33 on the Billboard Hot 100.[22]

- Anita Bryant performed it January 17, 1971, at the halftime show of Super Bowl V. She would also do it again on January 25, 1973, during the burial services for LBJ at his Texas ranch.[23]

Influence

[edit]Popularity and widespread use

[edit]In the years since the Civil War, "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" has been used frequently as an American patriotic song.[24]

Cultural influences

[edit]The lyrics of "Battle Hymn of the Republic" appear in Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s sermons and speeches, most notably in his speech "How Long, Not Long" from the steps of the Alabama State Capitol building on March 25, 1965, after the successful Selma to Montgomery march, and in his final sermon "I've Been to the Mountaintop", delivered in Memphis, Tennessee, on the evening of April 3, 1968, the night before his assassination. The speech ends with the first lyrics of the "Battle Hymn": "Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord."

Bishop Michael B. Curry of North Carolina, after his election as the first African American Presiding Bishop of The Episcopal Church, delivered a sermon to the Church's General Convention on July 3, 2015, in which the lyrics of the "Battle Hymn" framed the message of God's love. After proclaiming "Glory, glory, hallelujah, His truth is marching on", a letter from President Barack Obama was read, congratulating Bishop Curry on his historic election.[25] Curry is known for quoting the "Battle Hymn" during his sermons.

The tune has played a role in many movies where patriotic music has been required, including the 1970 World War II war comedy Kelly's Heroes, and the 1999 sci-fi western Wild Wild West. Words from the first verse gave John Steinbeck's wife Carol Steinbeck the title of his 1939 masterpiece The Grapes of Wrath.[26] The title of John Updike's In the Beauty of the Lilies also came from this song, as did Terrible Swift Sword and Never Call Retreat, two volumes in Bruce Catton's Centennial History of the Civil War. Terrible Swift Sword is also the name of a board wargame simulating the Battle of Gettysburg.[27]

Words from the second last line of the last verse are paraphrased in Leonard Cohen's song "Steer Your Way".[28] It was originally published as a poem in The New Yorker magazine.[29] "As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free" becomes "As He died to make men holy, let us die to make things cheap".

In association with football/soccer

[edit]The refrain "Glory, glory, hallelujah!" has been adopted by fans of a number of sporting teams, most notably in the English and Scottish Premier Leagues. The popular use of the tune by Tottenham Hotspur can be traced to September 1961 during the 1961–62 European Cup. Their first opponents in the competition were the Polish side Górnik Zabrze, and the Polish press described the Spurs team as "no angels" due to their rough tackling. In the return leg at White Hart Lane, some fans then wore angel costumes at the match holding placards with slogans such as "Glory be to shining White Hart Lane", and the crowded started singing the refrain "Glory, glory, hallelujah" as Spurs beat the Poles 8–1, starting the tradition at Tottenham.[30] It was released as the B-side to "Ossie's Dream" for the 1981 Cup Final.

The theme was then picked up by Hibernian, with Hector Nicol's release of the track "Glory, glory to the Hibees" in 1963.[31][32] "Glory, Glory Leeds United" was a popular chant during Leeds' 1970 FA Cup run. Manchester United fans picked it up as "Glory, Glory Man United" during the 1983 FA Cup Final. As a result of its popularity with these and other British teams, it has spread internationally and to other sporting codes. An example of its reach is its popularity with fans of the Australian Rugby League team, the South Sydney Rabbitohs (Glory, Glory to South Sydney) and to A-League team Perth Glory. Brighton fans celebrate their 1970s legend by singing "Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord, he played for Brighton and Hove Albion and his name is Peter Ward".[citation needed]

Other songs set to this tune

[edit]Some songs make use of both the melody and elements of the lyrics of "Battle Hymn of the Republic", either in tribute or as a parody:

- "Marching Song of the First Arkansas" is a Civil War–era song that has a similar lyrical structure to "Battle Hymn of the Republic". It has been described as "a powerful early statement of black pride, militancy, and desire for full equality, revealing the aspirations of black soldiers for Reconstruction as well as anticipating the spirit of the civil rights movement of the 1960s".[33]

- The tune has been used with alternative lyrics numerous times. The University of Georgia's rally song, "Glory Glory to Old Georgia", is based on the patriotic tune, and has been sung at American college football games since 1909. Other college teams also use songs set to the same tune. One such is "Glory, Glory to Old Auburn" at Auburn University. Another is "Glory Colorado", traditionally played by the band and sung after touchdowns scored by the Colorado Buffaloes. "Glory Colorado" has been a fight song at the University of Colorado (Boulder) for more than one hundred years.

- In 1901 Mark Twain wrote "The Battle Hymn of the Republic, Updated", with the same tune as the original, as a comment on the Philippine–American War. It was later recorded by the Chad Mitchell Trio.

- "The Burning of the School" is a well-known parody of the song.[34]

- The United States Army paratrooper song, "Blood on the Risers", first sung in World War II, includes the lyrics "Gory, gory" in the lyrics, based on the original's "Glory, glory".

- A number of terrace songs (in association football) are sung to the tune in Britain. Most frequently, fans chant "Glory, Glory..." plus their team's name: the chants have been recorded and released officially as songs by Hibernian, Tottenham, Leeds United and Manchester United. The 1994 World Cup official song "Gloryland" interpreted by Daryl Hall and the Sounds of Blackness has the tune of "Battle Hymn of the Republic".[35] In Argentina the St. Alban's former Pupils Assn (Old Philomathian Club) used the tune for its "Glory Glory Philomathians" as well. While not heard often nowadays it is still a cherished song for the Old Philomathians.

- In Australia, the song is used by rugby league club the South Sydney Rabbitohs – "Glory Glory to South Sydney". Each verse ends with, "They wear the Red and Green".[36]

- The parody song "Jesus Can't Go Hashing", popular at Hash House Harrier events, uses the traditional melody under improvised lyrics. Performances typically feature a call-and-response structure, wherein one performer proposes an amusing reason why Jesus Christ might be disqualified from running a hash trail—e.g. "Jesus can't go Hashing 'cause the flour falls through his hands" or “Jesus can’t go Hashing ‘cause he turns the beer to wine” —which is then repeated back by other participants (mirroring the repetitive structure of "John Brown's Body"), before ending with the tongue-in-cheek proclamation "Jesus saves, Jesus saves, Jesus saves". A chorus may feature the repeated call of "Free beer for all the Hashers", or, after concluding the final verse, "Jesus, we're only kidding".[37]

- The parody song "Jesus Can't Play Rugby", popular at informal sporting events, uses the traditional melody under improvised lyrics. Performances typically feature a call-and-response structure, wherein one performer proposes an amusing reason why Jesus Christ might be disqualified from playing rugby—e.g. "Jesus can't play rugby 'cause his dad will rig the game"—which is then repeated back by other participants (mirroring the repetitive structure of "John Brown's Body"), before ending with the tongue-in-cheek proclamation "Jesus saves, Jesus saves, Jesus saves". A chorus may feature the repeated call of "Free beer for all the ruggers", or, after concluding the final verse, "Jesus, we're only kidding".[38]

- A protest song titled "Gloria, Gloria Labandera" (lit. "Gloria the Laundrywoman") was used by supporters of former Philippine president Joseph Estrada to mock Gloria Macapagal Arroyo after the latter assumed the presidency following Estrada's ouster from office, further deriving the "labandera" parallels to alleged money laundering.[39] While Arroyo did not mind the nickname and went on to use it for her projects, the Catholic Church took umbrage to the parody lyrics and called it "obscene".[40]

- The song itself is used in the 1998 film American History X as "The White Man Marches On" in which some of the neo-Nazi skinheads sing a hateful rendition of the song attacking blacks, Jews, and mixed-race people.

Other songs simply use the melody, i.e. the melody of "John Brown's Body", with no lyrical connection to "The Battle Hymn of the Republic":

- "Solidarity Forever", a marching song for organized labor in the 20th century.[41]

- The anthem of the American consumers' cooperative movement, "The Battle Hymn of Cooperation", written in 1932.

- The tune has been used as a marching song in the Finnish military with the words "Kalle-Kustaan muori makaa hiljaa haudassaan, ja yli haudan me marssimme näin" ("Carl Gustaf's hag lies silently in her grave, and we're marching over the grave like this").[42]

- The Finnish Ice Hockey fans can be heard singing the tune with the lyrics "Suomi tekee kohta maalin, eikä kukaan sille mitään voi" ("Finland will soon score, and no one can do anything about it").[43]

- The Estonian song "Kalle Kusta" uses the melody as well.

- The Swedish drinking song Halta Lotta (lit. "Limping Lotta") – referring to a pub in Gothenburg – uses the melody. The song tells how much a drink is worth at the pub in question (either 8 or 15 öre, depending on the version), how one can pay with kisses if one cannot afford a drink, how the recipient of these kisses is the landlady's sister given that the landlady is dead, where the landlady is buried and how her grave is desecrated by urinating dogs and how her body decays, eventually leading to the nationalization of the pub, which drives the prices up to 50 öre.[44]

- The folk dance "Gólya" ("Stork"), known in several Hungarian-speaking communities in Transylvania (Romania), as well as in Hungary proper, is set to the same tune. The same dance is found among the Csángós of Moldavia with a different tune, under the name "Hojna"; with the Moldavian melody generally considered original, and the "Battle Hymn" tune a later adaptation.[citation needed]

- The melody is used in French Canadian Christmas carol called "Glory, Alleluia", covered by Celine Dion and others.[45]

- The melody is used in the marching song of the Assam Regiment of the Indian Army: "Badluram Ka Badan", or "Badluram's Body", its chorus being "Shabash Hallelujah" instead of "Glory Hallelujah". The word "Shabash" in Hindustani means "congratulations" or "well done".

- The song "Belfast Brigade" using alternate lyrics is sung by the Lucky4 in support of the Irish Republican Army.

- The song "Up Went Nelson", celebrating the destruction of Nelson's Pillar in Dublin, is sung to this tune.

- The Discordian Handbook Principia Discordia has a version of the song called Battle Hymn of the Eristocracy.[46] It has been recorded for example by Aarni.[47]

- The Subiaco Football Club, in the West Australian Football League, uses the song for their team song. Also, the Casey Demons in the Victorian Football League also currently use the song. The words have been adjusted due to the song mainly being written during the period of time they were called the Casey Scorpions and the Springvale Football Club. As well as these two clubs, the West Torrens Football Club used the song until 1990, when their successor club, Woodville-West Torrens, currently use this song in the South Australian National Football League. The Broadbeach Cats also employ this melody for their theme song. Clarence Kangaroos and Wanderer Eagles use this as well.

- The Brisbane Bears, before they merged with the Fitzroy Football Club, used the "Battle Hymn of the Republic" in experiment mode before eventually scrapping it in favour of the original song.

- The melody is used in the well-known Dutch children's song "Lief klein konijntje". The song is about a cute little rabbit that has a fly on his nose. The British adaptation of the lyrics is thought to be "Little Peter Rabbit".[48]

- The melody is used as the theme for the Japanese electronics chain Yodobashi Camera.

- The melody is used in several Japanese nursery rhymes, including ともだち讃歌 ("Tomodachi Sanka") and ごんべさんの赤ちゃん ("Gonbei-san no aka-chan").[49]

- The melody has been used as a fight song in Queen's University, named "Oil Thigh".[50]

- The melody is used as Christmas carols in Indonesia, named "Nunga Jumpang Muse Ari Pesta I" in Batak Toba language, "Sendah Jumpa Kita Wari Raya E" in Karo language and "Sudah Tiba Hari Raya Yang Kudus" in Indonesian (all three translate as "Christmas Day is Coming").[51][52][53]

- The melody is used in "Hãy tiếp tục đoàn kết với Việt Nam" (Let's continue to unite with Vietnam), a song about Sino-Vietnamese war of 1979[54]

- The melody is used in Godiva's Hymn, a traditional drinking song for North American Engineers

Other settings of the text

[edit]Irish composer Ina Boyle set the text for solo soprano, mixed choir and orchestra; she completed her version in 1918.[55] The British Methodist Hymn Book used in the mid 20th century had Walford Davies's Vision as the first tune, and the Battle Hymn as the second tune.[56]

The progressive metal band Dream Theater utilise the lyrics of the Battle Hymn of the Republic at the end of their song "In the Name of God", the final song on their 2003 album Train of Thought.

See also

[edit]- "Battle Cry of Freedom"

- "Belfast Brigade"

- "Blood on the Risers"

- Children's street culture

- "Glory, Glory" (Georgia fight song)

- "Over There"

- "Solidarity Forever"

- William Weston Patton

- "Dixie", the Confederate equivalent.

References

[edit]- ^ Ken Burns' "Civil War" miniseries, episode 2

- ^ Reynolds, David S. "John Brown Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights." Vintage Books, pp. 209–215.

- ^ Stauffer, John; Soskis, Benjamin (2013). The Battle Hymn of the Republic: A Biography of the Song That Marches On. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199339587.

- ^ Stauffer & Soskis 2013, p. 18.

- ^ Stauffer & Soskis 2013, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Kimball 1890, p. 372.

- ^ Kimball 1890, pp. 373–4.

- ^ Cutler, Frederick Morse (1917), The old First Massachusetts coast artillery in war and peace (Google Books), Boston: Pilgrim Press, pp. 105–06

- ^ Cutler, Frederick Morse (1920). The 55th artillery (CAC) in the American expeditionary forces, France, 1918 (Google Books). Worcester, Massachusetts: Commonwealth Press. pp. 261ff.

- ^ Williams, Gary. Hungry Heart: The Literary Emergence of Julia Ward Howe. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999: 208. ISBN 1-55849-157-0

- ^ Julia Ward Howe, 1819–1910, vol. I, University of Pennsylvania, June 1, 1912, retrieved July 2, 2010. See also footnote in To-Day, 1885 (v.3, February), p.88

- ^ Howe, Julia Ward. Reminiscences: 1819–1899. Houghton, Mifflin: New York, 1899. p. 275.

- ^ Hall, Roger L. New England Songster. PineTree Press, 1997.

- ^ Howe, Julia Ward (February 1862). "The Battle Hymn of the Republic". The Atlantic Monthly. 9 (52): 10. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ^ Stossel, Sage (September 2001). "The Battle Hymn of the Republic". The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ^ Howe, Julia Ward. Battle hymn of the republic, Washington, D.C.:Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Regiments [n.d] "Battle hymn of the Republic. By Mrs. Julia Ward Howe. Published by the Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Regiments". Library of Congress. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "LDS Hymns #60". Hymns. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- ^ Methodist Conference (1933). The Methodist hymn-book with tunes. London: Methodist Conference Office. Hymn number 260.

- ^ 1862 sheet music https://www.loc.gov/resource/ihas.200000858.0/?sp=1

- ^ "Battle Hymn of the Republic (original version)". American music preservation. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ^ Sanders, Coyne Steven (1990). Rainbow's End: The Judy Garland Show. Zebra Books. ISBN 0-8217-3708-2.

- ^ Williams, Andy, Battle Hymn of the Republic (chart positions), Music VF, retrieved June 16, 2013

- ^ Johnson, Haynes; Witcover, Jules (January 26, 1973). "LBJ Buried in Beloved Texas Hills". The Washington Post. p. A1.

- ^ "Civil War Music: The Battle Hymn of the Republic". Civilwar.org. October 17, 1910. Archived from the original on August 16, 2012. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^ "Video: Presiding Bishop-elect Michael Curry preaches at General Convention Closing Eucharist". July 3, 2015.

- ^ DeMott, Robert (1992). Robert DeMott's Introduction to The Grapes of Wrath. USA: Viking Penguin. p. xviii. ISBN 0-14-018640-9.

- ^ "Terrible Swift Sword: The Battle of Gettysburg – Board Game". BoardGameGeek. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^ "You Want It Darker" Columbia Records, released Oct. 21, 2016

- ^ "Steer Your Way". The New Yorker.

- ^ Cloake, Martin (December 12, 2012). "The Glory Glory Nights: The Official Story of Tottenham Hotspur in Europe".

- ^ "Hector Nicol with the Kelvin Country Dance Band – Glory Glory To The Hi-Bees (Hibernian Supporters Song) (Vinyl, 7", 45 RPM, Single) – Discogs". Discogs. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ "Hector Nicol – Discography & Songs – Discogs". Discogs. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Walls, "Marching Song", Arkansas Historical Quarterly (Winter 2007), 401–402.

- ^ Dirda, Michael (November 6, 1988). "Where the Sidewalk Begins". The Washington Post. p. 16.

- ^ "Gloryland 1994 World Cup Song". YouTube. Archived from the original on November 2, 2021. Retrieved September 28, 2010.

- ^ "Rabbitohs Club Song". South Sydney Rabbitohs.

- ^ "Jesus Can't Go Hashing | Hash Song". Hash House Harriers.

- ^ "Informationen zum Thema Shamrocks Rugby Will County Rugby Chicago Rugby Manhattan Rugby". shamrockrfc.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ^ "Gloria doesn't mind 'labandera' tag". Philstar.com. Philstar Global Corp. May 5, 2001. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ Vanzi, Sol Jose. "PHNE: Business and Economy". www.newsflash.org. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Steffe, William (1862). "Solidarity Forever: Melody – 'Battle Hymn of the Republic'". Musica net. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ^ Uppo-Nalle (1991), Suomen kansallisfilmografia (2004), on ELONET, National Audiovisual Archive and the Finnish Board of Film Classification, "ELONET - Uppo-Nalle - Muut tiedot". Archived from the original on September 14, 2014. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- ^ "Varski Varjola – Suomi tekee kohta maalin (2011)". March 14, 2011. Archived from the original on November 2, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Dagens visa; 1999 juli 7". July 7, 1999. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ "Céline Dion chante noël". www.celinedion.com. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ "Principia Discordia – Page 11". Principia Discordia.

- ^ "Aarni – The Battle Hymn Of Eristocracy". October 23, 2011. Archived from the original on November 2, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Little Peter rabbit song (PDF), UK: Book trust, archived from the original (PDF) on November 2, 2013

- ^ "ごんべさんの赤ちゃん - (Gonbei-san no aka-chan)". Mama Lisa's World: Children's Songs and Rhymes from Around the World. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ "Oil Thigh". Queen's online encyclopedia. Queen's Webmaster. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ "KEE 114 Sendah Jumpa Kita Wari Raya E". GBKP KM 8 (in Indonesian). Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ "NUNGA JUMPANG MUSE ARI PESTA (BE 57)". Alkitab by Sabda. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ "SUDAH TIBA HARI RAYA YANG KUDUS (BN 57)". Alkitab by Sabda. Retrieved April 12, 2022.

- ^ "Hãy tiếp tục đoàn kết với Việt Nam" - Vietnamese War Song, retrieved October 22, 2022

- ^ "Works with Orchestra". Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ Methodist Conference (1933). The Methodist hymn-book with tunes. London: Methodist Conference Office. Number 260.

Sources

[edit]- Kimball, George (1890), "Origin of the John Brown Song", The New England Magazine, new, 1, Cornell University.

Further reading

[edit]- Claghorn, Charles Eugene, "Battle Hymn: The Story Behind The Battle Hymn of the Republic". Papers of the Hymn Society of America, XXIX.

- Clifford, Deborah Pickman. Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory: A Biography of Julia Ward Howe. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1978. ISBN 0316147478.

- Collins, Ace. Songs Sung, Red, White, and Blue: The Stories Behind America's Best-Loved Patriotic Songs. HarperResource, 2003. ISBN 0060513047.

- Hall, Florence Howe. The Story of the Battle Hymn of the Republic (Harper, 1916).

- Hall, Roger Lee. Glory, Hallelujah: Civil War Songs and Hymns, Stoughton: PineTree Press, 2012.

- Jackson, Popular Songs of Nineteenth-Century America, note on "Battle Hymn of the Republic", pp. 263–64.

- McWhirter, Christian. Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2012. ISBN 1469613670.

- Scholes, Percy A. "John Brown's Body", The Oxford Companion of Music. Ninth edition. London: Oxford University Press, 1955.

- Snyder, Edward D. "The Biblical Background of the 'Battle Hymn of the Republic,'" New England Quarterly (1951) 24#2, pp. 231–238. JSTOR 361364.

- Stauffer, John, and Benjamin Soskis. The Battle Hymn of the Republic: A Biography of the Song That Marches On (Oxford University Press; 2013) ISBN 978-0-19-933958-7. 380 pages. Traces the history of the melody and lyrics & shows how the hymn has been used on later occasions.

- Stutler, Boyd B. Glory, Glory, Hallelujah! The Story of "John Brown's Body" and "Battle Hymn of the Republic". Cincinnati: The C. J. Krehbiel Co., 1960. OCLC 3360355.

- Vowell, Sarah. "John Brown's Body," in The Rose and the Briar: Death, Love and Liberty in the American Ballad. Ed. by Sean Wilentz and Greil Marcus. New York: W. W. Norton, 2005. ISBN 0393059545.

External links

[edit]Sheet music

[edit]- Free sheet music of The Battle Hymn of the Republic from Cantorion.org

- 1917 Sheet Music at Duke University as part of the American Memory collection of the Library of Congress

- The Battle Hymn of the Republic. Facsimile of first draft

Audio

[edit]- "The Battle Hymn of the Republic", Stevenson & Stanley (Edison Amberol 79, 1908)—Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project.

- MIDI for The Battle Hymn of the Republic from Project Gutenberg

- The Battle Hymn of the Republic sung at Washington National Cathedral, mourning the September 11, 2001 attacks.

- The short film A NATION SINGS (1963) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.