|

|

Union states in the American Civil War |

|---|

|

|

| Dual governments |

| Territories and D.C. |

During the American Civil War, the state of Illinois was a major source of troops for the Union Army (particularly for those armies serving in the Western Theater of the Civil War), and of military supplies, food, and clothing. Situated near major rivers and railroads, Illinois became a major jumping off place early in the war for Ulysses S. Grant's efforts to seize control of the Mississippi and Tennessee rivers. Statewide, public support for the Union was high despite Copperhead sentiment.

The state was energetically led throughout the war by Governor Richard Yates. Illinois contributed 250,000 soldiers to the Union Army, ranking it fourth in terms of the total manpower in Federal military service. Illinois troops predominantly fought in the Western Theater, although a few regiments played important roles in the East, particularly in the Army of the Potomac. Several thousand Illinoisians were killed or died of their wounds during the war, and a number of national cemeteries were established in Illinois to bury their remains. In addition to President Abraham Lincoln, a number of other Illinois men became prominent in the army or in national politics, including generals, Ulysses S. Grant, John M. Schofield and John A. Logan, Senator Lyman Trumbull, and Representative Elihu P. Washburne. No major battles were fought in the state, although several river towns became sites for important supply depots and "brownwater" navy yards. Several prisoner of war camps and prisons dotted the state after 1863, processing thousands of captive Confederate soldiers.

However, not everyone in the state supported the war. In fact, there were even calls for secession in Southern Illinois or Little Egypt by several residents. In Marion residents voted to secede from the United States. A few, even, volunteered for the Confederate States Army in Tennessee. Thirty-four men, while Frank Metcalf claimed they were forty-five,[1] from the southern tip of the state, were recruited from Jackson and Williamson County, joined Company G, "The Illinois Company", of the 15th Tennessee Regiment Volunteer Infantry.[2] This can be attributed to the region's close cultural and economic ties to the South since many Southerners had migrated there. However, the movement for secession soon fizzled after the proposal was blocked and shelved.

Eighteen counties of southern Illinois formed the congressional district of Democrat John A. Logan. Rumors abounded in early 1861 whether he would organize his supporters and join the Confederacy. In fact he was suppressing pro-Confederate elements, and organizing his supporters to fight for the Union. Lincoln made him a general, and Logan played a major role under generals Grant and Sherman. His men marched to war as Democrats; they marched home as Republicans. Later, Logan helped found the Grand Army of the Republic veteran organization, was elected to the United States Senate as a Republican, and was the Republican vice presidential nominee in 1884.[3][4] As a precaution, Union troops remained in Little Egypt for the remainder of the war.[5] Confederate sentiment would remain alive in Southern Illinois amid the growing Copperhead political movement in the North.

History

[edit]

During the Civil War, 256,297 people from Illinois served in the Union army, more than any other northern state except for New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio. Beginning with Illinois resident President Lincoln's first call for troops and continuing throughout the war, the state mustered 150 infantry regiments, which were numbered from the 7th Illinois to the 156th Illinois. Seventeen cavalry regiments were also mustered, as well as two light artillery regiments.[6] Due to enthusiastic recruiting rallies and high response to voluntary calls to arms, the military draft was little used in Chicago and its environs, but was a factor in supplying manpower to Illinois regiments late in the war in other regions of the state. Camp Douglas, located near Chicago, was one of the largest training camps for these troops, as well as Camp Butler near Springfield. Both served as leading prisoner-of-war camps for captive Confederates. Another significant POW camp was located at Rock Island. Several thousand Confederates died while in custody in Illinois prison camps and are buried in a series of nearby cemeteries. There were no Civil War battles fought in Illinois, but Cairo, at the juncture of the Ohio River with the Mississippi River, became an important Union supply base, protected by Camp Defiance. Other major supply depots were located at Mound City and across the Ohio river at Fort Anderson in Paducah, Kentucky, along with sprawling facilities for the United States Navy gunboats and associated river fleets. One of which would take part in the nearby Battle of Lucas Bend. Leading major generals with Illinois ties included Ulysses S. Grant, John Buford, John Pope, John M. Schofield, John A. Logan, John A. McClernand, Benjamin Prentiss and Stephen Hurlbut. Brigadier General Elon J. Farnsworth, who began his career in the 8th Illinois Cavalry, died at the Battle of Gettysburg. President Lincoln maintained his home in Springfield, Illinois, where he is buried. Over 100 soldiers from Illinois units would earn the Medal of Honor during the conflict.

Union home-front support

[edit]The Chicago city government and voluntary societies gave generous support to soldiers during the war.[7] Composer and music publisher George Frederick Root gained fame and fortune from a number of well-received war songs, including The Battle Cry of Freedom and others. A pair of Chicago-based women, Mary Livermore and Jane Hoge, organized a pair of large expositions, the Northwest Sanitary Fairs, where cash generated from the sale of donated items was later used to purchase medical supplies for the soldiers. Their activities helped spark the postbellum women's rights movement in Illinois. Mary Ann Bickerdyke, a resident of Galesburg, was a noted nurse for the Western armies. Workers in various factories and mills, as well as the port and stockyards, helped provide a steady source of materiel, food, and clothing to Illinois troops, as well as to the general Union army. Mound City foundry workers converted river steamboats into armored gunboats for Federal service. With traditional Southern markets cut off by the war, the port of Chicago rose in prominence as Illinois expanded trade with the Great Lakes region. Chicago meatpackers earned venture capital during the war that was reinvested in 1865, as the war ended, to create the Northern city's Union Stock Yards.

War politics

[edit]During the 1860 Presidential Election, two men from Illinois were among the four major candidates. Illinois voted in favor of Springfield resident Abraham Lincoln (172,171 votes or 50.7% of the ballots cast) over Chicagoan Stephen Douglas (160,215; 47.2%). Of minor consequence in the statewide results were Southern candidates John C. Breckinridge (2,331; 0.7%), and John Bell (4,914; 1.5%).[8] Throughout the war, Illinois politics were dominated by Republicans under the energetic leadership of Governor Richard Yates and Senators Lyman Trumbull and Orville H. Browning. Democrats scored major gains in the 1862 election by attacking Lincoln's emancipation plan as danger to the state since it would bring in thousands of freed slaves.[9] As a result, the Democrats had a majority in the legislature and in 1863, Browning's Senate seat, formerly held by Douglas prior to the war, was filled by the Democrats with the election of William Alexander Richardson. In the 1864 presidential election, Illinois residents supported Lincoln's re-election, giving the president 189,512 votes (54.4% of the total) to General George McClellan's 158,724 votes (45.6%).[10] Within a year, Lincoln was dead and his remains had been returned to Springfield for burial.

Confederate Homefront support

[edit]Copperheads

[edit]Opposition views of the Peace Democrats (or "Copperheads") filled the columns of The Chicago Times, the mouthpiece of the rival Democratic Party. It was the nation's loudest and most persistent critic of Lincoln and emancipation. At one point early in the Gettysburg Campaign in June 1863, Union troops forcibly closed the newspaper at bayonet point. It was only reopened when Democratic mobs threatened to destroy the rival Republican paper and President Lincoln intervened.[11] Barry shows that Amos Green (1826–1911) from Paris, Illinois, was a leading lawyer and Peace Democrat (Copperhead). Green saw the War as unjust and Lincoln as a despot who had to be stopped. He wrote vicious denunciations of the administration in local newspapers. He was arrested for sedition in 1862. After his release in August 1862, he became the grand commander of the secret Order of American Knights in Illinois, which fought restrictions on civil liberties. It was also called the Knights of the Golden Circle and later the Sons of Liberty. Green was funded by the Confederate government to arrange riots at the Democratic National Convention in 1864. Although the riots never materialized, he continued giving antigovernment speeches until he was again arrested in November 1864. After this arrest, he agreed to testify for the government about the activities of the Knights; his testimony implicated others but ignored his own deep involvement in antigovernment plots.[12] In 1864, a clash between Copperheads and Union Soldiers in Charleston, Illinois resulted in nine dead and twelve wounded in what is now called the "Charleston Riot".

Notable leaders from Illinois

[edit]-

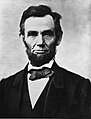

Pres.

Abraham Lincoln -

Lt. Gen.

Ulysses S. Grant -

Gov.

Richard Yates -

Sen.

Lyman Trumbull -

Maj. Gen.

John Buford -

Maj. Gen.

John Pope -

Maj. Gen.

John M. Schofield -

Maj. Gen.

John A. Logan -

Maj. Gen.

John A. McClernand -

Maj. Gen.

Benjamin Grierson -

Maj. Gen.

Stephen A. Hurlbut -

Maj. Gen.

Benjamin Prentiss -

Maj. Gen.

Richard J. Oglesby -

Bvt. Maj. Gen

Elias Smith Dennis -

Bvt. Maj. Gen

John Aaron Rawlins -

Brig. Gen.

W.H.L. Wallace -

Brig. Gen.

Elon J. Farnsworth

Among the many Illinois generals who rose to post-war prominence were Ulysses S. Grant, who became president in 1869, Green B. Raum, who became a U.S. congressman and the Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service, and James L. Alcorn, who was a U.S. Senator and the Governor of Mississippi. Both were born near Golconda. Galena-born John Aaron Rawlins, long a confidant of U.S. Grant, became the United States Secretary of War in the Grant Administration. John M. Palmer, a resident of Carlinville, was a postbellum Governor of Illinois and the presidential candidate of the National Democratic Party in the 1896 election. Edward S. Salomon, an immigrant from Europe, was appointed by President Grant as the Governor of the Washington Territory. William P. Carlin of Carrollton became a general in the postbellum U.S. Army and commanded several outposts in Montana and elsewhere.

A number of soldiers from Illinois regiments would eventually become governors of U.S. states. Among them were John Marshall Hamilton, future governor of Illinois; Albinus Nance, future governor of Nebraska; John St. John, future governor of Kansas; and Samuel Rinnah Van Sant, future governor of Minnesota.

See also

[edit]- List of Illinois Civil War Units

- Bibliography of the American Civil War

- Bibliography of Abraham Lincoln

- Bibliography of Ulysses S. Grant

- William R. Rowley, aide-de-camp on General Grant's staff

References

[edit]- Cole, Arthur Charles, The Era of the Civil War, 1848–1870, (Sesquicentennial History of Illinois, Vol 3) (ISBN 0-252-01339-5) (1919, reprinted 1987), outstanding scholarly history covering politics, economy and society.

- Hicken, Victor, Illinois in the Civil War, University of Illinois Press, 1991, a scholarly history focused on the soldiers.

- Illinois in the Civil War[usurped]. Retrieved February 1, 2005.

- Chicago History. Retrieved August 7, 2006.

- Northern Illinois University's Illinois During the Civil War website. Retrieved August 8, 2006.

- Leip, David. "1860 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 27, 2005.

- Leip, David. "1864 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 27, 2005.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Metcalf, Frank. "The Illinois Confederate Company," Confederate Veteran, vol. 16, pp.224-5. S.A. Cunningham, 1908.

- ^ 15th Tennessee Volunteer Infantry - Company G, The Confederate Army's Southern Illinois Company, Illinois in the Civil War website[usurped]

- ^ William S. Morris; et al. (1998). History 31st Regiment Illinois Volunteers Organized by John A. Logan. SIU Press. pp. 15–20.

- ^ James Pickett Jones (1995). Black Jack: John A. Logan and Southern Illinois in the Civil War Era. SIU Press. pp. 82–90.

- ^ "The Civil War and Late 19th Century" Archived 2012-02-23 at the Wayback Machine, The History of Southern Illinois, Egyptian Area on Aging, Inc., 1996–2009, accessed 15 May 2009

- ^ Illinois regiments during the Civil War Archived 2005-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kurt A. Carlson, "Backing the Boys in the Civil War: Chicago's Home Front Supports the Troops - and Grows in the Process," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Spring/Summer 2011, Vol. 104 Issue 1/2, pp 140-165

- ^ Leip, 1860

- ^ Bruce S. Allardice, "'Illinois is Rotten with Traitors!' The Republican Defeat in the 1862 State Election," . Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Spring/Summer 2011, Vol. 104 Issue 1/2, pp 97-114

- ^ Leip, 1864

- ^ Chicago History website

- ^ Peter J. Barry, "Amos Green, Paris, Illinois: Civil War Lawyer, Editorialist, and Copperhead," Journal of Illinois History, Spring 2008, Vol. 11 Issue 1, pp 39-60

Further reading

[edit]- Allardice, Bruce S. “‘Illinois is Rotten with Traitors!’ The Republican Defeat in the 1862 State Election,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 104 (Spring–Summer 2011), 97–114.

- Baker, Jason B. Chicago to Appomattox: The 39th Illinois Infantry in the Civil War (McFarland, 2022).

- Bearden-White, Christina. "Illinois Germans and the Coming of the Civil War: Reshaping Ethnic Identity" Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 109#3 (2016), pp. 231–251 DOI: 10.5406/jillistathistsoc.109.3.0231

- Bohn, Roger E. "Richard Yates: An Appraisal of his Value as the Civil War Governor of Illinois," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society Spring/Summer2011, Vol. 104 Issue 1/2, pp 17–37 in JSTOR

- Cole, Arthur Charles. The Era of the Civil War 1848–1870 (1919), the standard scholarly history; vol 3 of the Centennial History of Illinois.

- Costigan, David. A city in wartime: Quincy, Illinois and the Civil War (2021).

- Duerkes, Wayne N. "'I for one am ready to do my part': The initial motivations that inspired men from Northern Illinois to enlist in the U.S. Army, 1861–1862," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (2012) 105#4 pp 313–32 in JSTOR

- Dyer, Frederick H., A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion. 3 volumes. Thomas Yoseloff, reprinted 1959; covers every state

- Girardi, Robert I. "'I am for the President's Proclamation teeth and toe nails': Illinois Soldiers Respond to the Emancipation Proclamation." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 106#3-4 (2013) pp: 395–421. in JSTOR

- Gleeson, Ed. Illinois Rebels - A Civil War Unit History of G Company, 15th Tennessee Regiment Volunteer Infantry (1996, Guild Press of Indiana: Carmel, Indiana)

- Grossman, James R.. Ann Durkin Keating, and Janice L. Reiff, eds. The Encyclopedia of Chicago (2005) online version

- Hicken, Victor, Illinois in the Civil War, University of Illinois Press. 1991. ISBN 0-252-06165-9.

- Jones, James Pickett (1995). Black Jack: John A. Logan and Southern Illinois in the Civil War Era. SIU Press. p. 91ff.

- Jordan, Brian Matthew. Marching Home: Union Veterans and Their Unending Civil War (WW Norton & Company, 2015)

- Karamanski, Theodore J., Rally 'Round the Flag: Chicago and the Civil War. Nelson-Hall, 1993. ISBN 0-8304-1295-6.

- Kleen, Michael, “The Copperhead Threat in Illinois Peace Democrats, Loyalty Leagues, and the Charleston Riot of 1864,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 105 (Spring 2012), 69–92.

- Lentz, Perry. Key Command: Ulysses S. Grant's District of Cairo (University of Missouri Press, 2006)

- Levy, George. To Die in Chicago: Confederate Prisoners at Camp Douglas, 1862–65. (2nd ed. 1999) excerpt and text search.

- Metcalf, Frank. "The Illinois Confederate Company," Confederate Veteran, vol. 16, pp.224-5. S.A. Cunningham, 1908.

- Miller Jr, Edward A. The Black Civil War Soldiers of Illinois: The Story of the Twenty-Ninth US Colored Infantry (Univ of South Carolina Press, 2021).

- Pierce, Bessie Louise. A History of Chicago: Volume II: From Town to City 1848–1871 (1937)

- Swan, James B. Chicago's Irish Legion: The 90th Illinois Volunteers in the Civil War (Southern Illinois University Press, 2009)

Historiography and memory

[edit]- Karamanski, Theodore J. "Illinois at the High Tide: The Era of the Civil War, 1848–1870." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 111.1-2 (2018): 55–78. online

- Knoll, Jeremy. "Remembering the Fallen: The Creation of Civil War Monuments in Illinois, 1865–1929." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 114.2 (2021): 33–95.

Primary sources

[edit]- Burton, William L., Descriptive bibliography of Civil War manuscripts in Illinois. Civil War Centennial Commission of Illinois, Northwestern University Press, 1966.

- Flotow, Mark, ed. In Their Letters, in Their Words: Illinois Civil War Soldiers Write Home (Southern Illinois University Press, 2019).

- Office of the Adjutant General, Roster of Officers and Enlisted Men. 9 volumes, State Printing Office, 1900.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 volumes in 4 series. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1880–1901. online

- Voss-Hubbard, Mark, ed. Illinois's War: The Civil War in Documents. (Ohio University Press, 2013) 244 pp. online review

External links

[edit]- Illinois in the Civil War (Mike's Musings)

- Illinois in the Civil War (ILGenWeb Project)

- Illinois regiments during the Civil War[usurped]

- History of the 77th Illinois Volunteer Infantry, W. H. Bentley, 1883

- Civil War Flags of Illinois

- [1] Illinois During the Civil War, 1861–1865, Illinois Historical Digitization Projects at Northern Illinois University Libraries]

- Official Website dedicated to the memory of the 92nd Illinois Volunteer Mounted Infantry in America's Civil War Archived 2016-12-26 at the Wayback Machine

- State of Illinois: 150th Civil War Anniversary project