| Part of a series of articles on |

|

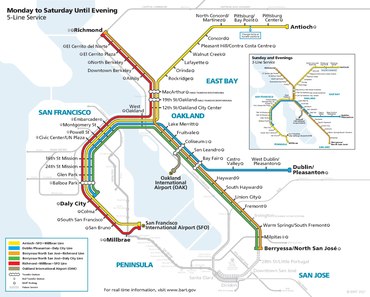

Throughout the history of Bay Area Rapid Transit, there have been plans to extend service to other areas.

History

[edit]BART Marin Line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The initial 1962 BART maps approved by voters included several lines beyond the core system marked as Possible Future Extensions.[1] Some have since come to fruition as previous extensions of the system:[2]

- The extension from Concord to Antioch was carried out in phases with service to North Concord / Martinez in 1995, Pittsburg / Bay Point in 1996, and the eBART spur which started service in 2018.

- A line to Livermore was completed as far as Dublin/Pleasanton by 1997, with final completion of the envisioned corridor to be carried out by Valley Link.

- Service south of Fremont is expected to reach San Jose and Santa Clara (partially via the Caltrain right of way) by 2030. It was extended to Warm Springs in 2017 and Berryessa in 2020.

- Extension from Daly City to the south was completed in phases as the Colma Station opened in 1996 and the line to Millbrae was completed in 2003 with a spur to San Francisco International Airport. The full Southern Pacific (now Caltrain) right of way has been electrified for frequent service with mainline trains, separate from BART.

- The Marin Line via Geary was initially cancelled due to the county exiting the planning district over funding and engineering issues. There were two possible routes: (1) via Geary to Park Presidio, then across the Golden Gate Bridge via rails that would have been built into the truss supports under the roadway, then after tunneling through the Waldo Grade to Marin City, would have emerged from underground and followed the old train tracks north through the county; (2) alternatively, to tunnel from Fort Mason/Aquatic Park to downtown Sausalito and follow the right-of-way from the old train tracks.

An additional corridor not part of the 1962 plan completed since the agency's inception is the automated guideway transit spur line that connects BART to Oakland International Airport which opened in 2014.[3]

Proposed extensions

[edit]San Jose subway extension (Phase 2)

[edit]

The original plan for the Silicon Valley extension was to continue into downtown San Jose and Santa Clara via subway. However, in February 2009, projections of lower-than-expected sales-tax receipts from the funding measures forced the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority to scale back the extension, ending it at the Berryessa/North San José station and delaying tunneling under downtown San Jose to a future phase of construction (making it essentially a "Phase 2" of the project). The originally-planned complete extension from Fremont to Santa Clara had been projected to cost $6.1 billion, but the VTA estimates the extension to Berryessa (Phase 1 only) would cost just $2.3 billion.[4][5]

The plans for the downtown subway start with a portal before crossing under US 101, with subway stations at 28th Street/Little Portugal, Downtown San Jose station (The Downtown San Jose station was combined in 2005 from earlier plans for separate subway stations at Civic Plaza/San Jose State University and Market Street.),[6] and Diridon/Arena. The line would exit to the surface after crossing under I-880 and terminate at a Santa Clara BART station co-located at the existing Santa Clara Depot. Separate construction plans by San Jose International Airport would bring a people-mover train to either the Santa Clara Depot or to Diridon Station.[7]

For the subway segment in San Jose, VTA plans to use a tunnel boring machine for most of the length in order to reduce disruptions to downtown during construction.[8] Only the station locations would have cut and cover construction.[9] This is different from how BART subways and stations were built in San Francisco and Oakland, which used the cut and cover method. The construction of the cut and cover stations in downtown San Jose would still cause major albeit temporary disruption, including closing several blocks of Santa Clara Street and severing the VTA light rail line at that street. The extension to downtown San Jose could open 2026, contingent on approval of funding.[10] As of April 2018, the plan was to have a single-bore tunnel under Santa Clara Street with cut and cover construction at the station locations only.[11] Utility relocation started and soil samples were taken in February 2019, with construction to begin in 2022.[12][13]

Funding and electoral history (2000–2008)

[edit]Because Santa Clara County is not among the member counties of the BART District (having opted out at the district's inception, like neighboring San Mateo County), VTA is responsible for building the extension within Santa Clara County. VTA allocated initial funds for constructing BART using the proceeds from a sales tax referendum which was passed by Santa Clara County voters in 2000. In December 2002, VTA purchased a freight railroad corridor from Union Pacific Railroad which will serve as much of the necessary right-of-way for both the Warm Springs and San Jose extensions for $80 million.[14]

In 2004, the Federal Transit Administration decided to wait to fund the project, citing worries that BART did not have enough money to operate the extension.[15] In addition, the San Jose extension project received a "not recommended" rating from the Federal Transit Administration, placing the federal portion of the funding in jeopardy because of concerns about operation and maintenance funding.[16]

Santa Clara County voters passed Measure B in 2008, a 1⁄8-cent sales tax raise.[17] Projections by an independent consultant recommended by the Federal Transit Administration predicted that the 1⁄8-cent sales tax would more than cover operation and maintenance of the proposed extension.[18][19][20][21]

San Jose voters passed Measure B in 2016, which allowed for final funding of the subway.[22][8]

Livermore extension: I-580/Tri-Valley Corridor

[edit]A proposed extension will further service from Dublin/Pleasanton station east to Livermore, either via traditional BART infrastructure, diesel multiple unit technology[23][24] similar to eBART, or enhanced bus service.[25] It could possibly continue over the Altamont Pass into Tracy and the Central Valley along I-580 and/or go north through Dublin, San Ramon, Danville, and Alamo to the existing Walnut Creek station via the I-680 corridor.

An existing diesel commuter rail line, the Altamont Corridor Express (ACE), currently operates through Livermore. The two systems are linked, though not directly, by a free shuttle bus which transfers passengers between the ACE Pleasanton station and the BART Dublin/Pleasanton station.[26][27][28]

A preferred alignment was selected July 1, 2010 and originally had the support of the Livermore City Council. This plan would have involved the construction of a station in downtown Livermore, and a second station on Vasco Road near Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and Sandia National Laboratories. Both proposed stations would have provided nearby connections to Altamont Corridor Express service.[29] However, in July 2011, the Livermore City Council reversed its position in response to a petition requesting that the alignment stay within or nearby the Interstate 580 right-of-way, and now favors stations be built at the Interstate 580 interchanges with Isabel Avenue and Greenville Road.[30] BART's Environmental Impact Report Notice of Preparation, issued in September 2012, proposed a single station at I-580 and Isabel Avenue, with possible express bus services connecting to the Vasco Road ACE station and a park-and-ride lot at I-580 and Greenville Road.[31] Land use plans and studies were being prepared by the city of Livermore in September 2015, with completion envisioned in 2026.[25][32][33] Additional funding for consulting and planning were allocated in late 2016, against the wishes of then BART District President Tom Radulovich.[34] On July 31, 2017, BART released the Draft Environmental Impact Report of the project.[citation needed] The direct BART to ACE connection was studied in preparation for ACEforward projects.[citation needed]

In 2017, citing lack of interest in the project from BART, the Livermore City Council proposed a newly established local entity to undertake planning and construction of the extension,[35] which was also recommended by the California State Assembly Transportation Committee.[24] The Tri-Valley–San Joaquin Valley Regional Rail Authority was established that year "for purposes of planning, developing, and delivering cost-effective and responsive transit connectivity between the Bay Area Rapid Transit District's rapid transit system and the Altamont Corridor Express commuter rail service in the Tri-Valley, that meets the goals and objectives of the community."[36] On May 24, 2018, the BART board voted against a full rapid transit BART build or a bus rapid transit system to extend service east from Dublin/Pleasanton station, thus granting the new authority oversight and funding for constructing a new service called the Valley Link. Moneys previously allocated to BART to construct a Livermore extension were forfeited to the authority by July 1, 2018.[37]

BART Metro Vision

[edit]Key components of the overall vision for BART's future, dubbed BART Metro Vision, include more capacity in stations, increased train frequency to allow for "show up and go" service at stations within the system's operational core, and increased performance reliability. The most recent report from BART Metro Vision also identifies improvements to its rolling stock, the Hayward Maintenance Complex, and the modernization of its train control system as key improvements for securing the system's long-term viability.[38]

Second Transbay crossing

[edit]Part of BART's 50th anniversary service planning included a new separate Transbay Tube beneath San Francisco Bay running parallel to and south of the existing tube. This would emerge at the Salesforce Transit Center to provide connecting service to Caltrain and the planned California High-Speed Rail (CAHSR) system. The additional four-bore Transbay Tube would provide two additional tracks for BART trains, and two tracks for conventional/high-speed rail (the BART system and conventional U.S. rail use different and incompatible rail gauges, and operate under different sets of safety regulations).[39]

Transit advocacy groups in the Bay Area, such as SPUR,[40] have long promoted larger-scale expansion of the BART system through various capital projects - one identified as a long-term goal in the Metro Vision is the construction of a second, four-bore rail tunnel under San Francisco Bay, increasing connectivity and capacity of the system. The second crossing would likely route to the Salesforce Transit Center for connections with conventional mainline rail services. In 2018, BART announced that a feasibility study for installing a second transbay crossing would commence the following year.[41] By 2019, the Capitol Corridor Joint Powers Authority had joined with BART to study a multi-modal crossing, which could also allow Capitol Corridor and San Joaquin routes to serve San Francisco directly.[42]

In 2021, the Link21 program was announced, using funding from Regional Measure 3. The program initially proposed a 4-track transbay crossing for both BART and commuter rail; however, this was pared back to 2 tracks. The likely long-term plan is for the second transbay crossing to be electrified commuter rail, connecting Caltrain (which is partially governed by BART) to the Capitol Corridor.[43]

eBART extension

[edit]Expansions of the DMU-serviced eBART system come at a lower cost-per-mile than conventional wide-gauge BART infrastructure. Service could extend to Oakley,[44][45] Byron, or Brentwood.[46]

Geary Subway

[edit]Part of the plan for the original system before Marin County's departure from the BART District was a line running under Geary Street and turning north to the Golden Gate Bridge. When Marin County pulled out of the transit district, some plans called for a subway only extending down Geary, but these too were soon scrapped. In 1995, the San Francisco Municipal Railway hired Merrill & Associates to study the possibility of building a new BART subway beneath Geary in conjunction with adding light rail on the surface. The estimated cost of construction as far as Park Presidio Boulevard was $1.4 billion in 1995 ($2.8 billion adjusted for inflation). Projections from this study put BART ridership at 18,000 daily boardings, and the alignment would allow for a further extension to Marin. These plans were dropped, according to former Senator Quentin L. Kopp, due to merchant and resident opposition, citing potential blight similar to that caused by Market Street Subway construction two decades earlier.[47]

Ongoing studies will determine whether the corridor may one day be served by future BART service. It may be constructed as an extension of the second Transbay Tube.[39][47]

wBART extension

[edit]The only branch of the original BART system that has not been extended since service commenced is the line ending at Richmond station. Possible alignments for an extension further north were examined in 1983,[48] 1992,[49] and 2017.[50] Both newly constructed BART wide-gauge electrified rail and the use of existing freight rail rights of way and tracks with more readily available standard gauge trains were considered. Potential station locations include Hilltop Mall, Pinole, and Hercules Transit Center. The cost of an extension to Hercules Transit Center utilizing mainline BART technology was estimated at $3.6 billion in 2017 with a ridership of 21,980 by 2040.[51] The extension to Hercules is controversial in that the main proponent wants to build it directly from the El Cerrito del Norte BART station while the city of Richmond is very opposed to this. Furthermore, the majority of the Hercules city council opposes the extension as they believe it will detract from their plan to develop Hercules station.[52][53][54][55]

I-680 Corridor

[edit]Service in the Tri-Valley area had previously been considered with diesel multiple service originating at Walnut Creek and running as far east as Tracy.[56] As part of BART's 50th anniversary and envisioning another fifty years of service, planners foresaw a new East Bay alignment originating at Warm Springs station and running via Interstate 680 to the Martinez Amtrak station. It would connect to the existing stations at Dublin / Pleasanton and Walnut Creek.[39]

Menlo Park extension

[edit]In 1999, a short-lived proposal to extend BART from the Millbrae station (then under construction) to Menlo Park was advanced by the San Mateo County Economic Development Association (SAMCEDA). The proposed routing would have paralleled the Caltrain tracks to Broadway station in Burlingame, and then would run along the median of Bayshore Freeway to Menlo Park, with stations in San Mateo, Belmont/San Carlos, Redwood City, and Menlo Park. Cost estimates ranged up to US$2,500,000,000 (equivalent to $4,570,000,000 in 2023), drawing funding from a 1/2-cent sales tax increase in San Mateo County.[57] BART leadership warned the timing was not appropriate for a push further south into San Mateo County, and SAMCEDA withdrew the proposal by the summer of 1999.[58]

Infill stations

[edit]Infill stations are stations constructed on existing line segments between two existing stations. The Embarcadero (1976) and West Dublin/Pleasanton (2011) stations are the only infill stations currently in the BART system. The Doolittle Maintenance and Storage Facility, initially slated to be opened as a full station along the Oakland Airport Connector, may be repurposed for passenger service at a later date.

Construction costs for a planned 30th Street Mission station in San Francisco, between the existing 24th Street Mission and Glen Park stations, were estimated at $500 million in 2003.[59][60] A proposal for a Jack London Square station in Oakland was rejected in 2004 as being incompatible with existing track geometry; a one-station stub line at the foot of Broadway and the use of other transit modes also were studied.[61] BART planners studied additional stations at four other sites within the system in 2007: Albany, Calaveras, Irvington, and 30th Street Mission.[38] Other potential stations noted in 2014 included a station at 30th Street/Mission in San Francisco, an infill station between Richmond and El Cerrito del Norte, and four Oakland stations at Children's Hospital Oakland, San Antonio/Brooklyn Basin, Melrose and Elmhurst.[62]

The City of Fremont re-evaluated the Irvington station's environmental impact report in 2017, and a station area plan was adopted by the Fremont City Council and approved by the BART Board of Directors in 2019.[63][64] As of January 2019[update], estimates from the city anticipated construction to begin in 2022, with the Irvington station opening for service in 2026.[64]

References

[edit]- ^ "The Composite Report Bay Area Rapid Transit". Archive.org. Parsons Brinckerhoff / Tudor / Bechtel. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ "Celebrating 40 Years of Service 1972 • 2012 Forty BART Achievements Over the Years" (PDF). Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). 2012. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ^ "New BART service to Oakland International Airport now open". Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). November 21, 2014. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ^ Childress, Brandi (March 12, 2012). "VTA and FTA Seal the Deal for BART Silicon Valley". VTA News. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ "BART to Berryessa: Sales tax projections force VTA to scale back plans". San Jose Mercury News. February 27, 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2009.

- ^ "Minutes of Silicon Valley Rapid Transit Corridor BART Extension Policy Advisory Board Meeting". Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA). June 22, 2005. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- ^ "San Jose, CA - Official Website - Automated Transit Network". www.sanjoseca.gov. Archived from the original on April 14, 2018. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Meacham, Jody (January 23, 2017). "Are you ready for a subway? Digging for BART begins in two years". Silicon Valley Business Journal. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ "Downtown San Jose Subway Fact Sheet" (PDF). Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA). May 14, 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- ^ "South Bay BART initiatives move forward". KGO-TV ABC San Francisco. May 8, 2009. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2010.

- ^ "VTA Board Approves Staff Recommendation for BART Silicon Valley Phase II Project". www.vta.org. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ Plater, Roz (January 20, 2019). "BART Construction Prep to Cause Delays in Downtown San Jose". NBC. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ^ "Santa Clara VTA first agency to submit expedited federal funding request for BART Phase II". Mass Transit. June 29, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ "Union Pacific closes land and track sale to VTA". Silicon Valley/San Jose Business Journal. December 2002. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- ^ Tom, Bulger (February 24, 2005). "February 2005 Monthly Report for MTC". Government Relations Inc. Archived from the original (DOC) on December 29, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ "History of BART to the South Bay". San Jose Mercury News. January 8, 2005. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ "LIST OF LOCAL MEASURES PRESIDENTIAL GENERAL ELECTION" (PDF). COUNTY OF SANTA CLARA 2/3 Vote. November 4, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 19, 2008.

- ^ "BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING - AGENDA". Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA). August 7, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ "Measure B reaches two-thirds approval in late vote counting". San Jose Mercury News. November 17, 2008. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- ^ "BART backers pop open champagne, celebrate vision for San Jose's Grand Central Station". San Jose Mercury News. November 21, 2008. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- ^ "November 4 Presidential Primary Election SUMMARY RESULTS - MEASURE B". Santa Clara County Government. November 21, 2008. Archived from the original on November 16, 2008. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- ^ Lin II, Rong-Gong (November 9, 2016). "Bay Area voters supporting BART renovation and extension to downtown San Jose". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ "Livermore Extension". BART. January 23, 2013. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Matthews, Sam (April 28, 2017). "Closer to a BART connection". Tracy Press. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ a b "BART Pauses Planning for Dublin Parking Garage". The Independent. February 16, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ "Pleasanton Station | ACE Rail Stations". Altamont Commuter Express. Archived from the original on July 3, 2010. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ "Wheels - Timetables - Route 54 - Pleasanaton Fairgrounds ACE Shuttle". Livermore Amador Valley Transit Authority. Archived from the original on April 19, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ "Wheels - Fares and Sales". Livermore Amador Valley Transit Authority. Archived from the original on August 1, 2010. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ "BART Board selects alignment for Livermore extension". Transbayblog.com. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- ^ Courtney, Jennifer (July 12, 2011). "City Council OKs Initiative to Keep BART on I-580". Livermore Patch. Archived from the original on September 10, 2011. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ "BART to Livermore Extension Project". Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). June 12, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ Richards, Gary (December 18, 2015). "Roadshow: BART down I-680 not a consideration". San Jose Mercury News. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- ^ "Isabel BART Station Plans in the Works". The Independent. September 17, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ Matier, Phil; Ross, Andy (October 3, 2016). "Politicians look for way to link BART to Central Valley". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ Angela Ruggiero, Angela Ruggiero (April 11, 2017). "Livermore says BART board doesn't care, wants local control". Vallejo Times-Herald. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ "AB-758 Transportation: Tri-Valley-San Joaquin Valley Regional Rail Authority". Retrieved October 17, 2017.

- ^ Baldassari, Erin (May 24, 2018). "BART rejects Livermore expansion; mayor vows rail connection". East Bay Times. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ a b "BART Metro Vision Update" (PDF). Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). April 25, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b c Cabanatuan, Michael (June 22, 2007). "BART's New Vision: More, Bigger, Faster". San Francisco Chronicle. p. A1. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- ^ Rudick, Roger (April 20, 2016). "SPUR Meeting Pushes Second Transbay Tube". Streetsblog SF. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ Fortson, Jobina (November 15, 2018). "BART considering 2nd Transbay Tube, 24 hour service". ABC 7 KGO-TV. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ Bizjak, Tony (February 20, 2019). "How trains under the bay - not high-speed rail - may connect Sacramento and San Francisco". Sacramento Bee. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ "Link21".

- ^ Szymanski, Kyle. "eBART extension to Brentwood still a distant idea". The Press. Brentwood, California: Brentwood Press & Publishing. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ CDM Smith. "eBART Next Segment Study" (PDF). Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ "BART: Board vote brings commuter rail closer to Brentwood". The Mercury News. May 12, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Rodriguez, Joe Fitzgerald (October 19, 2019). "BART looking west toward Geary Boulevard in transbay crossing study". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- ^ Drake, Gerard. "West Contra Costa Extension Study Final Report" (PDF). Wilbur Smith and Associates. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 13, 2016. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ "West Contra Costa Extension Alignment Study" (PDF). Korve Engineering, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 13, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ "West Contra Costa High-Capacity Transit Study" (PDF). West County High-Capacity Transit Study. West Contra Costa Transportation Advisory Committee. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ Radin, Rick (March 28, 2017). "West Contra Costa studying I-80 corridor gridlock solutions". East Bay Times. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- ^ "BART extension to Hercules still being studied and 'sorely needed,' director says | Richmond Standard". Archived from the original on March 29, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- ^ "BART extension to Hercules raises questions about housing density and station location". May 13, 2013.

- ^ "Hercules says no to BART extension study". May 16, 2013.

- ^ "Should BART Extend to Pinole and Hercules?". March 26, 2013.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (June 13, 2003). "BART ponders eastern extensions / Planned routes call for unfamiliar trains". San Francisco Gate. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ "SAMCEDA 1999 proposal for BART via 101 to Menlo Park". Bay Rail Alliance. June 27, 2004. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- ^ Softky, Marion (July 21, 1999). "Plan dumped to extend BART down Bayshore Freeway to Menlo Park". The Almanac News. Menlo Park. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- ^ John T. Warren and Associates Inc (May 2003). "Cost Estimates" (PDF). Feasibility Study for an Infill BART Station in San Francisco, at 30th & Mission Streets. Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). p. 64. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ Topakian, Karen (May 2002). "A 30th Street BART Station Would Cost Half a Billion and Take 7 Years to Get Here". The Noe Valley Voice. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ "The Jack London BART Feasibility Study" (PDF). Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). December 2004. pp. 17–31. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ "BART Vision Plan" (PDF). Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART). 2015. p. 6. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ Geha, Joseph (March 30, 2017). "Fremont: Irvington BART site to be re-evaluated for almost $3 million". East Bay Times. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ a b "Irvington BART Station". City of Fremont. Retrieved October 8, 2019.