| Murad III | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ottoman Caliph Amir al-Mu'minin Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques | |||||

Life-size portrait, attributed to a Spanish artist, 17th century | |||||

| Sultan of the Ottoman Empire (Padishah) | |||||

| Reign | 27 December 1574 – 16 January 1595 | ||||

| Predecessor | Selim II | ||||

| Successor | Mehmed III | ||||

| Born | 4 July 1546 Manisa, Ottoman Empire | ||||

| Died | 16 January 1595 (aged 48) Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire | ||||

| Burial | Hagia Sophia, Istanbul | ||||

| Consorts | |||||

| Issue Among others | Hümaşah Sultan Ayşe Sultan Mehmed III Şehzade Mahmud Şehzade Selim Fatma Sultan Mihrimah Sultan Fahriye Sultan | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Ottoman | ||||

| Father | Selim II | ||||

| Mother | Nurbanu Sultan | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

| Tughra |  | ||||

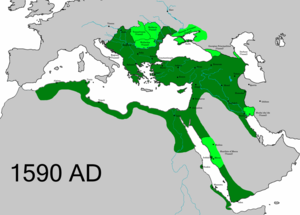

Murad III (Ottoman Turkish: مراد ثالث, romanized: Murād-i sālis; Turkish: III. Murad; 4 July 1546 – 16 January 1595) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1574 until his death in 1595. His rule saw battles with the Habsburgs and exhausting wars with the Safavids. The long-independent Morocco was for a time made a vassal of the empire but regained independence in 1582. His reign also saw the empire's expanding influence on the eastern coast of Africa. However, the empire was beset by increasing corruption and inflation from the New World which led to unrest among the Janissary and commoners. Relations with Elizabethan England were cemented during his reign, as both had a common enemy in the Spanish. He was also a great patron of the arts, commissioning the Siyer-i-Nebi and other illustrated manuscripts.

Early life

[edit]Born in Manisa on 4 July 1546,[1] Şehzade Murad was the oldest son of Şehzade Selim and his powerful wife Nurbanu Sultan. He received a good education and learned the Arabic and Persian languages. After his ceremonial circumcision in 1557, Murad's grandfather, the Sultan Suleiman I, appointed him sancakbeyi (governor) of Akşehir in 1558. At the age of 18 he was appointed sancakbeyi of Saruhan. Suleiman died in 1566 when Murad was 20, and his father became the new sultan, Selim II. Selim II broke with tradition by sending only his oldest son out of the palace to govern a province, assigning Murad to Manisa.[2]: 21–22

Reign

[edit]Selim died in 1574 and was succeeded by Murad, who began his reign by having his five younger brothers strangled.[3] His authority was undermined by harem influences – more specifically, those of his mother and later of his favorite concubine Safiye Sultan, often to the detriment of Sokollu Mehmed Pasha's influence on the court.[4] Selim's power had only been maintained by the effective leadership of the powerful Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, who remained in office until his assassination in October 1579. During Murad's reign, the northern borders with the Habsburg monarchy were defended by the Bosnian governor Hasan Predojević. The reign of Murad III was marked by exhausting wars on the empire's western and eastern fronts. The Ottomans also suffered defeats in battles such as the Battle of Sisak.

Expedition to Morocco

[edit]Abd al-Malik became a trusted member of the Ottoman establishment during his exile. He made the proposition of making Morocco an Ottoman vassal in exchange for the support of Murad III in helping him gain the Saadi throne.[5]

With an army of 10,000 men, most of whom were Turks, Ramazan Pasha and Abd al-Malik left from Algiers to install Abd al-Malik as an Ottoman vassal ruler of Morocco.[6] Ramazan Pasha conquered Fez which caused the Saadi Sultan to flee to Marrakesh which was also conquered. Abd al-Malik then assumed rule over Morocco as a client of the Ottomans.[7][5][8]

Abd al-Malik made a deal with the Ottoman troops by paying them a large amount of gold and sending them back to Algiers, suggesting a looser concept of vassalage than Murad III may have thought.[5] Murad's name was recited in the Friday prayer and stamped on coinage marking the two traditional signs of sovereignty in the Islamic world.[9] The reign of Abd al-Malik is understood to be a period of Moroccan vassalage to the Ottoman Empire.[10][11] Abd al-Malik died in 1578 and was succeeded by his brother Ahmad al-Mansur who formally recognised the suzerainty of the Ottoman Sultan at the start of his reign while remaining de facto independent. He stopped minting coins in Murad's name, dropped his name from the Khutba and declared his full independence in 1582.[12][13]

War with the Safavids

[edit]

The Ottomans had been at peace with the neighbouring rivaling Safavid Empire since 1555, per the Treaty of Amasya, that for some time had settled border disputes. But in 1577 Murad declared war, starting the Ottoman–Safavid War (1578–1590), seeking to take advantage of the chaos in the Safavid court after the death of Shah Tahmasp I. Murad was influenced by viziers Lala Kara Mustafa Pasha and Sinan Pasha and disregarded the opposing counsel of Grand Vizier Sokollu. Murad also fought the Safavids which would drag on for 12 years, ending with the Treaty of Constantinople (1590), which resulted in temporary significant territorial gains for the Ottomans.[2]: 198–199

Ottoman activity in the Horn of Africa

[edit]During his reign, an Ottoman Admiral by the name of Mir Ali Beg was successful in establishing Ottoman supremacy in numerous cities in the Swahili coast between Mogadishu and Kilwa.[14] Ottoman suzerainty was recognised in Mogadishu in 1585 and Ottoman supremacy was also established in other cities such as Barawa, Mombasa, Kilifi, Pate, Lamu, and Faza.[15][16]

Financial affairs

[edit]Murad's reign was a time of financial stress for the Ottoman state. To keep up with changing military techniques, the Ottomans trained infantrymen in the use of firearms, paying them directly from the treasury. By 1580 an influx of silver from the New World had caused high inflation and social unrest, especially among Janissaries and government officials who were paid in debased currency. Deprivation from the resulting rebellions, coupled with the pressure of over-population, was especially felt in Anatolia.[2]: 24 Competition for positions within the government grew fierce, leading to bribery and corruption. Ottoman and Habsburg sources accuse Murad himself of accepting enormous bribes, including 20,000 ducats from a statesman in exchange for the governorship of Tripoli and Tunisia, thus outbidding a rival who had tried bribing the Grand Vizier.[2]: 35

During his period, excessive inflation was experienced, the value of silver money was constantly played, food prices increased. 400 dirhams should be cut from 600 dirhams of silver, while 800 was cut, which meant 100 percent inflation. For the same reason, the purchasing power of wage earners was halved, and the consequence was an uprising.[17]

English pact

[edit]Numerous envoys and letters were exchanged between Elizabeth I and Sultan Murad III.[18]: 39 In one correspondence, Murad entertained the notion that Islam and Protestantism had "much more in common than either did with Roman Catholicism, as both rejected the worship of idols", and argued for an alliance between England and the Ottoman Empire.[18]: 40 To the dismay of Catholic Europe, England exported tin and lead (for cannon-casting) and ammunition to the Ottoman Empire, and Elizabeth seriously discussed joint military operations with Murad III during the outbreak of war with Spain in 1585, as Francis Walsingham was lobbying for a direct Ottoman military involvement against the common Spanish enemy.[18]: 41 This diplomacy would be continued under Murad's successor Mehmed III, by both the sultan and Safiye Sultan alike.

Personal life

[edit]Palace life

[edit]Following the example of his father Selim II, Murad was the second Ottoman sultan who never went on campaign during his reign, instead spending it entirely in Constantinople. During the final years of his reign, he did not even leave Topkapı Palace. For two consecutive years, he did not attend the Friday procession to the imperial mosque—an unprecedented breaking of custom. The Ottoman historian Mustafa Selaniki wrote that whenever Murad planned to go out to Friday prayer, he changed his mind after hearing of alleged plots by the Janissaries to dethrone him once he left the palace.[19] Murad withdrew from his subjects and spent the majority of his reign keeping to the company of few people and abiding by a daily routine structured by the five daily Islamic prayers. Murad's personal physician Domenico Hierosolimitano described a typical day in the life of the sultan:

In the morning he rises at dawn to say his prayer for half an hour, then for another half-hour he writes. Then he is given something pleasant as a collation, and afterwards sets himself to read for another hour. Then he begins to give audience to the members of the Divan on the four days of the week that this occurs, as had been said above. Then he goes for a walk through the garden, taking pleasure in the delight of fountains and animals for another hour, taking with him the dwarves, buffoons and others to entertain him. Then he goes back once again to studying until he considers the time for lunch has arrived. He stays at table only half an hour, and rises (to go) once again into the garden for as long as he pleases. Then he goes to say his midday prayer. Then he stops to pass the time and amuse himself with the women, and he will stay one or two hours with them, when it is time to say the evening prayer. Then he returns to his apartments or, if it pleases him more, he stays in the garden reading or passing the time until evening with the dwarfs and buffoons, and then he returns to say his prayers, that is at nightfall. Then he dines and takes more time over dinner than over lunch, making conversation until two hours after dark, until it is time for prayer [...] He never fails to observe this schedule every day.[2]: 29–30

Özgen Felek argues that Murad's sedentary lifestyle and lack of participation in military campaigns earned him the disapproval of Mustafa Âlî and Mustafa Selaniki, the major Ottoman historians who lived during his reign. Their negative portrayals of Murad influenced later historians.[2]: 17–19

Children

[edit]Before becoming sultan, Murad had been loyal to Safiye Sultan, his Albanian concubine. His monogamy was disapproved of by Nurbanu Sultan, who worried that Murad needed more sons to succeed him in case Mehmed died young. She also worried about Safiye's influence over her son and the Ottoman dynasty. Five or six years after his accession to the throne, Murad was given a pair of concubines by his sister Ismihan. Upon attempting sexual intercourse with them, he proved impotent. "The arrow [of Murad], [despite] keeping with his created nature, for many times [and] for many days has been unable to reach at the target of union and pleasure," wrote Mustafa Ali. Nurbanu accused Safiye and her retainers of causing Murad's impotence with witchcraft. Several of Safiye's servants were tortured by eunuchs in order to discover a culprit. Court physicians, working under Nurbanu's orders, eventually prepared a successful cure, but a side effect was a drastic increase in sexual appetite; by the time Murad died, he was said to have fathered over a hundred children.[2]: 31–32 Nineteen of these were executed by Mehmed III when he became sultan.

Women at court

[edit]Influential ladies of his court included his mother Nurbanu Sultan, his sister Ismihan Sultan, wife of grand vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, and musahibes (favourites) mistress of the housekeeper Canfeda Hatun, mistress of financial affairs Raziye Hatun, and the poet Hubbi Hatun, Finally, after the death of his mother and older sister, Safiye Sultan was the only influential woman in the court.[20][21]

Eunuchs at court

[edit]Before Murad, the palace eunuchs had been mostly white, especially Circassians or Syrians.[22] This began to change in 1582 when Murad gave an important position to a black eunuch.[23] Before, the eunuchs' roles in the palace were racially determined: black eunuchs guarded the harem and the princesses, and white eunuchs guarded the Sultan and male pages in another part of the palace.[24] The chief black eunuch was known as the Kizlar Agha, and the chief white eunuch was known as the Kapi Agha.

Murad and the arts

[edit]

Murad took great interest in the arts, particularly miniatures and books. He actively supported the court of Society of Miniaturists, commissioning several volumes including the Siyer-i Nebi, the most heavily illustrated biographical work on the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, the Book of Skills, the Book of Festivities and the Book of Victories.[25] He had two large alabaster urns transported from Pergamon and placed on two sides of the nave in the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople and a large wax candle dressed in tin which was donated by him to the Rila monastery in Bulgaria is on display in the monastery museum.

Murad also furnished the content of Kitabü’l-Menamat (The Book of Dreams), addressed to Murad's spiritual advisor, Şüca Dede. A collection of first person accounts, it tells of Murad's spiritual experiences as a Sufi disciple. Compiled from thousands of letters Murad wrote describing his dream visions, it presents a hagiographic self-portrait. Murad dreams of various activities, including being stripped naked by his father and having to sit on his lap,[2]: 72 single-handedly killing 12,000 infidels in battle,[2]: 99 walking on water, ascending to heaven, and producing milk from his fingers.[2]: 143

In another letter addressed to Şüca Dede, Murad wrote "I wish that God, may He be glorified and exalted, had not created this poor servant as the descendant of the Ottomans so that I would not hear this and that, and would not worry. I wish I were of unknown pedigree. Then, I would have one single task, and could ignore the whole world."[2]: 171

The diplomatic edition of these dream letters have been recently published by Ozgen Felek in Turkish.

Death

[edit]Murad died from what is assumed to be natural causes in the Topkapı Palace on 16 January 1595 and was buried in a tomb next to the Hagia Sophia. In the mausoleum are 54 sarcophagus of the sultan, his wives and children that are also buried there. He is also responsible for changing the burial customs of the sultans' mothers. Murad had his mother Nurbanu buried next to her husband Selim II, making her the first consort to share a sultan's tomb.[2]: 33–34

Family

[edit]Consorts

[edit]Murad is believed to have had Safiye Sultan as his only concubine for circa fifteen years. However, Safiye was opposed by Murad's mother, Nurbanu Sultan, and by his sister, Ismihan Sultan, and around 1580, she was exiled to the Old Palace on charges of having rendered the sultan impotent with a spell, after he had not succeeded or had not wanted to have sex with two concubines received by his sister. Furthermore, Nurbanu was concerned about the future of the dynasty, as she believed that Safiye's son alone, Mehmed, (two of three sons that Safiye gave to Murad were dead before 1580) were not enough to ensure the succession. After Safiye's exile, revoked only after Nurbanu's death on December 1583, Murad, to deny the rumor about his impotency, took a huge number of concubines and he had more than fifty known children, although according to sources the total number could exceed hundred.[26]

At time of his death in 1595, Murad had at least thirty-five concubines, amongs others:[27]

- Safiye Sultan, an ethnic Albanian. Haseki Sultan of Murad and Valide sultan of Mehmed III;[28]

- Şemsiruhsar Hatun, mother of Rukiye Sultan. She commissioned Koranic readings of prayers in the Prophet's mosque in Medina. She died before 1623.[27]

- Mihriban Hatun;[27]

- Şahıhuban Hatun; she commissioned a school in Fatih, where she is buried[27]

- Nazperver Hatun; she commissioned a mosque in Eyüp[27]

- Zerefşan Hatun[27]

- Fakriye Hatun[29]

- A concubine who died in August 1591, along with their stillborn son and were interred together.[30]

- Fiveteen pregnant concubines were placed in sacks and tossed into the Sea of Marmara, where they drowned, in 1595, by order of Mehmed III.[31]

- A concubine seduced and made pregnant by Mehmed III when he was a prince. The act was a violation of the rules of the harem, so Mehmed’s grandmother, Nurbanu Sultan, ordered the girl to be drowned in order to protect her grandson.

After the death of Murad III many of his concubines who became childless when at his accession Mehmed had his half-brothers killed, and others who never had children by Murad, were remarried off to palace officials, such as door keepers, cavalry forces (bölük halkı), and sergeants (çavus).[32][33]

Sons

[edit]Murad III had at least 27 known sons.

On Murad's death in 1595 Mehmed III, his eldest son and new sultan, son of Safiye Sultan, executed the 19 half-brothers still alive and drowned seven pregnant concubines, fulfilling the Law of Fraticide.

Known sons of Murad III are:

- Sultan Mehmed III (26 May 1566, Manisa Palace, Manisa – 22 December 1603, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Mehmed III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque, Constantinople), with Safiye Sultan, became the next sultan;

- Şehzade Selim (1567, Manisa Palace, Manisa - 25 May 1577, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople), with Safiye Sultan.

- Şehzade Mahmud (1568, Manisa Palace, Manisa – before 1580, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Selim II Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque), with Safiye Sultan.

- Şehzade Fülan (June 1582, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - June 1582, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople. buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque). Stillbirth.

- Şehzade Cihangir (February 1585, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - August 1585, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque); twin of Şehzade Süleyman.

- Şehzade Süleyman (February 1585, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - 1585, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque); twin of Şehzade Cihangir.

- Şehzade Abdüllah (1585, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Mustafa (1585, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Abdürrahman (1585, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Bayezid (1586, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Hasan (1586, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - died 1591, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Cihangir (1587, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Yakub (1587, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Ahmed (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - before 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Fülan (August 1591, stillbirth);

- Şehzade Alaeddin (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Davud (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Alemşah (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Ali (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Hüseyin (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Ishak (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Murad (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Osman (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - died 1587, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Yusuf (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Korkud (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Ömer (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

- Şehzade Selim (?, Topkapi Palace, Constantinople - murdered 28 January 1595, Topkapı Palace, Constantinople, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque);

In addition to these, a European braggart, Alexander of Montenegro, claimed to be the lost son of Murad III and Safiye Sultan, presenting himself with the name of Şehzade Yahya and claiming the throne for it. His claims were never proven and appear dubious to say the least.[34]

Daughters

[edit]Murad had more than thirty daughters still alive at his death in 1595, of whom nineteen died of plague (or smallpox) in 1598.[35][32]

It is not known if and how many daughters may have died before him.

Known daughters of Murad III are:

- Hümaşah Sultan (Manisa, c. 1564 - Costantinople, 1625 : 168 ); buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque) - with Safiye Sultan. Also called Hüma Sultan.[36] She married Nişar Mustafazade Mehmed Pasha (died 1586). She may have then married Serdar Ferhad Pasha (d.1595) in 1591.[37] She was lastly married in 1605 to Nakkaş Hasan Pasha (died 1622);[38][39][40][41][42]

- Ayşe Sultan (Manisa, c. 1565 - Costantinople, 15 May 1605, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque) - with Safiye Sultan. Married firstly on 20 May 1586, to Ibrahim Pasha,[39] married secondly on 5 April 1602, to Yemişçi Hasan Pasha, married thirdly on 29 June 1604, to Güzelce Mahmud Pasha.[40][43]

- Fatma Sultan (Manisa, c. 1573 - Costantinople, 1620, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque) - with Safiye Sultan. Married first on 6 December 1593, to Halil Pasha,[39][43] married second December 1604, to Cafer Pasha;[40] married third 1610 Hizir Pasha, married fourth Murad Pasha.

- Mihrimah Sultan (Costantinople, 1578/1579 - after 1625 ; buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque[44]) - possibly with Safiye Sultan;[40][45]

- Fahriye Sultan (died in 1656, buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque[44]), - possibly with Safiye Sultan, perhaps born after her return from exile in Old Palace. Called also Fahri Sultan.[46][38] She married firstly to Cuhadar Ahmed Pasha, Governor of Mosul, married secondly to Sofu Bayram Pasha, Governor of Bosnia (died in 1633);,[43][47][48]: 168 married thirdly to Deli Dilaver Pasha (died 1668).: 168 [49]

- Rukiye Sultan (buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque) - with Şemsiruhsar Hatun.[43][27][39][40][50]

- Mihriban Sultan (buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque)[43] married in 1613;[39]

- Hatice Sultan (1583 - 1648,: 168 buried in Şehzade Mosque[51]), was married in 1598 to Sokolluzade Lala Mehmed Pasha and had two sons and a daughter.[52] She participated in the reparation of the minarets of Bayezid Veli Mosque inside Kerch Fortress in 1599.[53] After widowed, in 1613 she married Gürşci Mehmed Pasha of Kefe, governor of Bosnia.[40][54][48]: 168

- Fethiye Sultan (buried in Murad III Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque).

- Beyhan Sultan (died fl. 1648[55]), married in 1613 to Vizier Kurşuncuzade Mustafa Pasha;[40][54][48][55]: 168

- Sehime Sultan,[46] married in 1613 to Topal Mehmed Pasha, formerly a Kapucıbaşı;[40][54][39][48][55]: 168

- A daughter married to Davud Pasha;[39]

- A daughter married in 1613 to Kücük Mirahur Mehmed Agha;[40][54]

- A daughter married in 1613 to Mirahur-i Evvel Muslu Agha;[40][54]

- A daughter married in 1613 to Bostancıbaşı Hasan Agha;[40][54]

- A daughter married in 1613 to Cığalazade Mehmed Bey (son of Cığalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha and Safiye Hanimsultan);[40][54]

- Nineteen daughters, died of plague in 1598;

- A daughter who died young on 29 July 1585.[56]

In fiction

[edit]- Murad is portrayed by the Romanian actor Colea Rautu in the historic epic film Michael the Brave.

- Orhan Pamuk's historical novel Benim Adım Kırmızı (My Name is Red, 1998) takes place at the court of Murad III, during nine snowy winter days of 1591, which the writer uses in order to convey the tension between East and West. Murad is not specifically named in the book, and is referred to only as "Our Sultan".

- The Harem Midwife by Roberta Rich - a historical fiction set in Constantinople (1578) which follows Hannah, a midwife, who tends to many of the women in Sultan Murad III's harem.

- In the 2011 TV series Muhteşem Yüzyıl, Murad III is portrayed by Turkish actor Serhan Onat.

References

[edit]- ^ "Murad III". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Felek, Özgen. (2010). Re-creating image and identity: Dreams and visions as a means of Murad III's self-fashioning. PhD Thesis. University of Michigan. Ann Arbor: ProQuest/UMI. (Publication No. 3441203).

- ^ Marriott, John Arthur. The Eastern Question (Clarendon Press, 1917), 96.

- ^ "Murad III | Ottoman sultan". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Akyeampong, Emmanuel Kwaku; Gates (Jr.), Henry Louis (2 February 2012). Dictionary of African Biography. OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-538207-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 3 - J. D. Fage: Pg 408

- ^ هيسبريس تمودا Volume 29, Issue 1 Editions techniques nord-africaines, 1991

- ^ Hess, Andrew (1978). The Forgotten Frontier : A History of the Sixteenth-Century Ibero-African Frontier. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-33031-0

- ^ Itzkowitz, Norman (15 March 1980). Ottoman Empire and Islamic Tradition. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226388069 – via Google Books.

- ^ Barletta, Vincent (15 May 2010). Death in Babylon: Alexander the Great and Iberian Empire in the Muslim Orient: Pages 82 and 104. University of Chicago Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-226-03739-4.

- ^ "Langues et littératures". Faculté des lettres et des sciences humaines. 9 September 1981 – via Google Books.

- ^ Rivet, Daniel (2012). Histoire du Maroc: de Moulay Idrîs à Mohammed VI. Fayard

- ^ A Struggle for the Sahara:Idrīs ibn ‘Alī’s Embassy toAḥmad al-Manṣūr in the Context ofBorno-Morocco-Ottoman Relations, 1577-1583 Rémi Dewière Université de Paris Panthéon Sorbonne

- ^ Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (9 September 1993). The Portuguese Empire in Asia, 1500-1700: A Political and Economic History. Longman. ISBN 9780582050693 – via Google Books.

- ^ Loimeier, Roman (17 July 2013). Muslim Societies in Africa: A Historical Anthropology. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253027320 – via Google Books.

- ^ Bosworth, C. Edmund (31 August 2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. BRILL. ISBN 9789047423836 – via Google Books.

- ^ Sakaoğlu 2008, p. 172.

- ^ a b c Karen Ordahl Kupperman (2007). The Jamestown project. Harvard University Press. p. 39. ISBN 9780674024748.

- ^ Karateke, Hakan T. "On the Tranquility and Repose of the Sultan." The Ottoman World. Ed. Christine Woodhead. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2011. p. 118.

- ^ Maria Pia Pedani Fabris, Alessio Bombaci (2010). Inventory of the Lettere E Scritture Turchesche in the Venetian State Archives. BRILL. p. 26. ISBN 978-90-04-17918-9.

- ^ Petruccioli, Attilio (1997). Gardens in the Time of the Great Muslim Empires: Theory and Design. E. J. Brill. p. 50. ISBN 978-90-04-10723-6.

- ^ Von Schierbrand, Wolf (28 March 1886). "Salve Sold to the Turk" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ Gamm, Niki (25 May 2013). "The black eunuchs and the Ottoman dynasty". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ Booth, Marilyn (2010). Harem Histories: Envisioning Places and Living Spaces. Duke University Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-8223-4869-6.

- ^ Pamuk, Orhan. My Name is Red, Alfred A. Knopf, 2010. ISBN 978-0-307-59392-4

- ^ Peirce, Leslie P. (1993). The imperial harem : women and sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. New York. pp. 94–95, 259. ISBN 0-19-507673-7. OCLC 27811454.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Altun, Mustafa (2019). Yüzyıl Dönümünde Bir Valide Sultan: Safiye Sultan'ın Hayatı ve Eserleri. pp. 20–21.

- ^ Mustafa Çağatay Uluçay, Padışahların kadınları ve kızları, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, 1980, pp. 42-6

- ^ Alderson, A.D.; The structure of the Ottoman Dynasty

- ^ "Tarih-i Selaniki 1-2 : Selânik Mustafa Efendi, d. 1600? : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". Internet Archive. 25 March 2023. p. 251. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ Jenkins, E. (2015). The Muslim Diaspora (Volume 2, 1500-1799): A Comprehensive Chronology of the Spread of Islam in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-4766-0889-1.

- ^ a b Argit, B.İ. (2020). Life after the Harem: Female Palace Slaves, Patronage and the Imperial Ottoman Court. Cambridge University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-108-48836-5.

- ^ Pazan, İbrahim (6 June 2023). "A Comparison of Seyyid Lokman's Records of the Birth, Death and Wedding Dates of Members of Ottoman Dynasty (1566-1595) with the Records in Ottoman Chronicles". Marmara Türkiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi. 10 (1). Marmara University: 245–271. doi:10.16985/mtad.1120498. ISSN 2148-6743.

- ^ Tezcan, Baki (2001). Searching For Osman: A Reassessment Of The Deposition Of Ottoman Sultan Osman II (1618-1622). pp. 327–8 n. 17.

- ^ Disease and Empire: A History of Plague Epidemics in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire (1453–1600). 2008. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-549-74445-0.

- ^ Sarinay, Yusuf (2000). 82 Numaralı Mühimme Defteri'nin (H.1026-1027/1617-1618) Transkripsiyonu ve Değerlendirilmesi. T.C. Başbakanlık Devlet Arşivleri Genel Müdürlüğü. p. 7.

- ^ Sakaoğlu, Necdet (2008). Bu mülkün kadın sultanları: Vâlide sultanlar, hâtunlar, hasekiler, kadınefendiler, sultanefendiler. Oğlak Yayıncılık. p. 217.

- ^ a b Miović 2018, p. 168.

- ^ a b c d e f g Peçevi, Ibrahim; Baykal, Bekir Sıtkı (1982). Peçevi Tarih, Volume 2. Başbakanlık Matbaası. p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Tezcan, Baki (2001). Searching For Osman: A Reassessment Of The Deposition Of Ottoman Sultan Osman II (1618-1622). pp. 328 n. 18.

- ^ Great Britain. Public Record Office (1900). Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts Relating to English Affairs: Existing in the Archives and Collections of Venice, and in Other Libraries of Northern Italy. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 442.

- ^ "Nakkaş Hasan Paşa". TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Uluçay, Mustafa Çağatay (2011). Padişahların kadınları ve kızları. Ankara: Ötüken. ISBN 978-975-437-840-5.

- ^ a b Demircanlı, Y.Y. (1989). İstanbul mimarisi için kaynak olarak Evliya Çelebi Seyahatnamesi. Vakıflar Genel Müdürlüğü. p. 599. ISBN 978-975-19-0121-7.

- ^ Uçtum, Nejat R. Hürrem ve Mihrümah sultanların Polonya Kralı II. Zigsmund'a Yazdıkları Mektuplar. p. 707.

- ^ a b Kahya, Ozan (2011). 11 numaralı İstanbul Mahkemesi defteri (H.1073) : tahlil ve metin (Thesis). pp. 219, 303–304.

- ^ Ayvansarayî, H.H.; Derin, F.Ç. (1978). Vefeyât-ı selâtîn ve meşâhı̂r-i ricâl. Yayınlar (İstanbul Üniversitesi. Edebiyat Fakültesi). Edebiyat Fakültesi Matbaası. p. 45.

- ^ a b c d Dumas, Juliette (2013). Les perles de nacre du sultanat: Les princesses ottomanes (mi-XVe – mi-XVIIIe siècle). p. 464.

- ^ Cikar, J. (2011). Türkischer Biographischer Index. De Gruyter. p. 290. ISBN 978-3-11-096577-3.

- ^ Fleet, Kate; Faroqhi, Suraiya N.; Kasaba, Reşat (2 November 2006). The Cambridge History of Turkey. Cambridge University Press. p. 412. ISBN 978-0-521-62095-6.

- ^ Turkey. Kültür Bakanlığı (1993). Dünden bugüne İstanbul ansiklopedisi. Kültür Bakanlığı. p. 20. ISBN 978-975-7306-04-7.

- ^ Bayrak, 1998, p. 43.

- ^ Öztuna, 1977. Başlangıcından zamanımıza kadar Büyük Türkiye tarihi, p. 125.

- ^ a b c d e f g Efendi, A.; Yılmazer, Z. (2003). Topçular Katibi ʻAbdülkādir (Kadrı) Efendi Tarihi: metin ve tahlıl. Publications de la Société d'histoire turque. Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi. p. 624. ISBN 978-975-16-1585-5.

- ^ a b c Miović, Vesna (2 May 2018). "Per favore della Soltana: moćne osmanske žene i dubrovački diplomati". Anali Zavoda Za Povijesne Znanosti Hrvatske Akademije Znanosti i Umjetnosti U Dubrovniku (in Croatian). 56 (56/1): 147–197. doi:10.21857/mwo1vczp2y. ISSN 1330-0598.

- ^ Pazan, İbrahim (6 June 2023). "A Comparison of Seyyid Lokman's Records of the Birth, Death and Wedding Dates of Members of Ottoman Dynasty (1566-1595) with the Records in Ottoman Chronicles". Marmara Türkiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi. 10 (1). Marmara University: 245–271. doi:10.16985/mtad.1120498. ISSN 2148-6743.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Murad III at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Murad III at Wikimedia Commons

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 14–15.

- Ancestry of Sultana Nur-Banu (Cecilia Venier-Baffo)