| Rocky | |

|---|---|

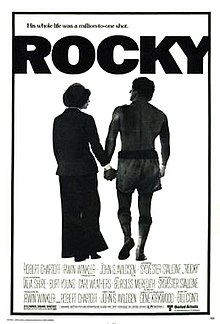

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John G. Avildsen |

| Written by | Sylvester Stallone |

| Produced by | |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | James Crabe |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Bill Conti |

Production company | Chartoff-Winkler Productions |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 119 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1,100,000 |

| Box office | $225 million[2] |

Rocky is a 1976 American independent[3] sports drama film directed by John G. Avildsen and written by and starring Sylvester Stallone. It is the first installment in the Rocky franchise and also stars Talia Shire, Burt Young, Carl Weathers, and Burgess Meredith. In the film, Rocky Balboa (Stallone), a poor small-time club fighter and loanshark debt collector from Philadelphia, gets an unlikely shot at the world heavyweight championship held by Apollo Creed (Weathers).

Rocky entered development in March 1975, after Stallone wrote the screenplay in three days. It entered a complicated production process after Stallone refused to allow the film to be made without him in the lead role; United Artists eventually agreed to cast Stallone after he rejected a six figure deal for the film rights. Principal photography began in January 1976, with filming primarily held in Philadelphia; several locations featured in the film, such as the Rocky Steps, are now considered cultural landmarks.[4] With an estimated production budget of under $1 million, Rocky popularized the rags to riches and American Dream themes of sports dramas which preceded the film.

Rocky had its premiere in New York City on November 20, 1976, and was released in the United States on December 3, 1976. Rocky became the highest-grossing film of 1976, earning approximately $225 million worldwide. The film received critical acclaim for Stallone's writing, as well as the film's performances, direction, musical score, cinematography and editing; among other accolades, it received ten Academy Award nominations and won three, including Best Picture. It has been ranked by numerous publications as one of the greatest films of all time, as well as one of the most iconic sports films ever.

Rocky and its theme song have become a pop-cultural phenomenon and an important part of 1970s American popular culture. In 2006, the Library of Congress selected Rocky for preservation in the United States National Film Registry as being "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant".[5][6] The first sequel in the series, Rocky II, was released in 1979.

Plot

[edit]In 1975, heavyweight boxing world champion Apollo Creed plans to hold a title bout in Philadelphia during the upcoming United States Bicentennial. However, he is informed five weeks from the fight date that his scheduled opponent is unable to compete due to an injured hand, and that all other potential replacements are either booked up or unable to get into shape in time. Having already invested heavily into the fight, Creed decides to give a local contender a chance to challenge him.

Creed selects Rocky Balboa, an Italian-American journeyman southpaw boxer who fights primarily in small gyms and works as a collector for a Mafia loan shark, on the basis of his nickname, "The Italian Stallion". Rocky fights in a local Philadelphia fight club, and he won his last fight with Spider Rico. He meets with promoter George Jergens, who tells him Creed has selected Rocky to fight him for the World Heavyweight Championship. Reluctant at first, Rocky eventually agrees to the fight, which will pay him $150,000. Rocky undergoes several weeks of unorthodox training, such as using sides of beef as punching bags.

Rocky is later approached by Mickey Goldmill, a former bantamweight fighter-turned-trainer whose gym Rocky frequents, about further training. Rocky is not willing initially, as Mickey has not shown much interest in helping him before and saw him as a wasted talent, but eventually Rocky accepts the offer.

Rocky begins to build a romantic relationship with Adrian Pennino, a shy woman who is working part-time at the J&M Tropical Fish pet store. Adrian's brother and Rocky's best friend, Paulie, helps Rocky get a date with his sister and offers to work as a cornerman with him for the fight, an offer Rocky turns down. Paulie becomes jealous of Rocky's success, but Rocky placates him by agreeing to advertise the meat packing business where Paulie works for sponsorship as part of the upcoming fight, and both of them reconcile. Rocky trains extensively for the championship fight, while Apollo is unconcerned about the match and puts more effort into promotion than training. The night before the match, Rocky visits the Spectrum and begins to lose confidence. He confesses to Adrian that he does not believe he can win, but strives to go the distance against Creed, which no other fighter has done, to prove himself to everyone.

On New Year's Day, the fight is held with Creed making a dramatic entrance dressed as George Washington and then Uncle Sam. Taking advantage of his overconfidence, Rocky knocks him down in the first round—the first time that Creed has ever been knocked down. Humbled and worried, Creed takes Rocky more seriously for the rest of the fight, though his ego never fully fades. The fight goes on for the full fifteen rounds, with both combatants sustaining various injuries: Rocky, with hits to the head and swollen eyes, requires his right eyelid to be cut to restore his vision, while Apollo, with internal bleeding and a broken rib, struggles to breathe. As the fight concludes, Creed's superior skill is countered by Rocky's apparently unlimited ability to absorb punches and his dogged refusal to go down. As the final bell sounds, with both fighters embracing each other, they promise each other there will be no rematch.

The fight is extremely well received by the sportscasters and the audience. Rocky calls out repeatedly for Adrian, who runs down as Paulie distracts security to help her get into the ring. As Jergens declares Creed the winner by virtue of a split decision, Rocky and Adrian embrace and profess their love for each other, not caring about the outcome of the fight.

Cast

[edit]

- Sylvester Stallone as Robert "Rocky" Balboa

- Talia Shire as Adriana "Adrian" Pennino

- Burt Young as Paulie Pennino

- Carl Weathers as Apollo Creed

- Burgess Meredith as Michael "Mickey" Goldmill

- Thayer David as George "Miles" Jergens

- Joe Spinell as Tony Gazzo

- Tony Burton as Tony "Duke" Evers

- Pedro Lovell as Spider Rico

- Stan Shaw as "Big Dipper" Brown

- Jodi Letizia as Marie

- Frank Stallone as Streetcorner Singer

- Joe Frazier as Himself

Production

[edit]Development and writing

[edit]Sylvester Stallone wrote the screenplay for Rocky in three and a half days, shortly after watching the championship match between Muhammad Ali and Chuck Wepner that took place at Richfield Coliseum in Richfield, Ohio, on March 24, 1975. Wepner was TKO'd in the 15th round of the match by Ali, with few expecting him to last as long as he did. Despite the match motivating Stallone to begin work on Rocky,[7] he has denied Wepner provided any inspiration for the script.[8][9][10] Other inspiration for the film may have included characteristics of real-life boxers Rocky Marciano and Joe Frazier,[11][12] as well as Rocky Graziano's autobiography Somebody Up There Likes Me and the movie of the same name. Wepner sued Stallone, and eventually settled for an undisclosed amount.[9]

Henry Winkler, Stallone's co-star in The Lords of Flatbush who then broke out as Arthur Fonzarelli on ABC's Happy Days, said he had taken the script to executives at the network. They expressed interest in turning it into a made-for-television movie and actually bought the script but insisted that someone else rewrite it. Upon hearing the news, Stallone begged Winkler not to let ABC change writers, so Winkler went back to the executives and offered to return the money in exchange for the rights. While ABC refused at first, Winkler said he was able to use his status as one of its biggest stars at the time to convince them to sell the rights back.[13]

At the time, Film Artists Management Enterprises (FAME), a joint venture between Hollywood talent agents Craig T. Rumar and Larry Kubik, represented Stallone. He submitted his script to Rumar and Kubik, who immediately saw the potential for it to be made into a motion picture. They shopped the script to various producers and studios in Hollywood but were repeatedly rejected because Stallone insisted that he be cast in the lead role. Eventually, they secured a meeting with Winkler-Chartoff productions (no relation to Henry Winkler). After repeated negotiations with Rumar and Kubik, Winkler-Chartoff agreed to a contract for Stallone to be the writer and also star in the lead role for Rocky.[14]

United Artists liked Stallone's script and viewed it as a vehicle for a well-established star like Robert Redford, Ryan O'Neal, Burt Reynolds, or James Caan.[15] Stallone's agents insisted that Stallone portray the title character, to the point of issuing an ultimatum. Stallone later said that he would never have forgiven himself had the film become a success with somebody else in the lead.[16][17] He also knew that producers Irwin Winkler and Robert Chartoff's contract with the studio enabled them to "greenlight" a project if the budget was kept low enough. The producers also collateralized any possible losses with their big-budget entry, New York, New York (whose eventual losses were covered by Rocky's success).[18][19] The film's production budget ended up being $1,075,000, with a further $100,000 spent on producers' fees and $4.2 million on advertising costs.[20]

Pre-production

[edit]Although Chartoff and Irwin Winkler were enthusiastic about the script and the idea of Stallone playing the lead character, they were hesitant about having an unknown headline the film. The producers also had trouble casting other major characters in the story, with Apollo Creed and Adrian cast unusually late by the production standards.[citation needed] Real-life boxer Ken Norton was initially sought for the role of Apollo Creed, but he pulled out and the role was ultimately given to Carl Weathers.[21] Norton, upon whom Creed was loosely based, fought Muhammad Ali three times. According to The Rocky Scrapbook, Carrie Snodgress was originally chosen to play Adrian, but a money dispute forced the producers to look elsewhere. Susan Sarandon and Cher auditioned for the role but Sarandon was deemed too pretty for the character and Cher too expensive. After Talia Shire's ensuing audition, Chartoff and Winkler, and director John Avildsen,[4] insisted that she play the part.[citation needed]

Philadelphia-based boxer Joe Frazier has a cameo appearance in the film. Outspoken boxer Muhammad Ali, who fought Frazier three times, influenced the character of Apollo Creed. During the 49th Academy Awards ceremony in 1977, Ali and Stallone staged a brief comic confrontation to show the film did not offend Ali. Frazier has claimed that some of the plot's most memorable moments—Rocky's carcass-punching scenes and Rocky running up the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art as part of his training regimen—are taken without credit from his own real-life exploits.[22]

Because of the film's comparatively low budget, members of Stallone's family played minor roles. His father rings the bell to signal the start and end of a round; his brother Frank plays a street corner singer, and his first wife, Sasha, was stills photographer.[23] Other cameos include former Philadelphia and then Los Angeles television sportscaster Stu Nahan playing himself, alongside radio and TV broadcaster Bill Baldwin; and Lloyd Kaufman, founder of the independent film company Troma, appearing as a drunk. Diana Lewis, then a news anchor in Los Angeles and later in Detroit, has a minor scene as a TV news reporter. Tony Burton appears as Apollo Creed's trainer, Tony "Duke" Evers, a role he would reprise throughout the entire Rocky series, though the character is not named until Rocky II. Michael Dorn, who would later gain fame as the Klingon Worf in Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, made his acting debut, albeit uncredited, as Creed's bodyguard.[24]

Filming

[edit]Principal photography for Rocky began on January 9, 1976.[25] Filming took place primarily throughout Philadelphia, with a few scenes being shot in Los Angeles. Rocky's house was in E Tusculum St 1818 in Philadelphia.[26] Inventor Garrett Brown's new Steadicam was used to accomplish smooth photography while running alongside Rocky during the film's Philadelphia street training sequences and the run up the Art Museum's flight of stairs, now colloquially known as the Rocky Steps.[27] It was also used for some shots in the fight scenes and can be seen at the ringside during some wide shots of the final fight. Rocky is often erroneously cited as the first film to use the Steadicam, although it was actually the third, after Bound for Glory and Marathon Man.[28]

Certain elements of the story were altered during filming. The original script had a darker tone: Mickey was portrayed as racist, and the script ended with Rocky throwing the fight after realizing he did not want to be part of the professional boxing world after all.[18]

Both Stallone and Weathers suffered injuries during the shooting of the final fight; Stallone suffered bruised ribs and Weathers suffered a damaged nose, the opposite injuries of what their characters had.[29]

The first date between Rocky and Adrian, in which Rocky bribes a janitor to allow them to skate after closing hours on a deserted ice skating rink, was shot that way due to budgetary concerns — the scene was originally scheduled to be shot in a public skating rink during regular business hours, but the producers decided they could not afford the hundreds of extras that would have been required.[30]

The poster seen above the ring before Rocky fights Apollo Creed shows Rocky wearing red shorts with a white stripe when he actually wears white shorts with a red stripe. When Rocky points this out, he is told that "it doesn't really matter, does it?" According to director Avildsen's DVD commentary, this was an actual mistake made by the props department that they could not afford to rectify, so Stallone wrote the brief scene to ensure the audience did not see it as a goof.[31] Conversely, Stallone has said he was indeed supposed to wear red shorts with a white stripe as Rocky, but changed to the opposite colors "at the last moment".[32] Similarly, when Rocky's robe arrived far too baggy on the day it was needed for filming, Stallone wrote in dialogue where Rocky points this out.[33]

Music

[edit]Soundtrack

[edit]Bill Conti composed the musical score for Rocky. He had composed a score for director John G. Avildsen's W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings (1975) that the studio ultimately rejected.[34] David Shire (then-husband of Talia Shire) was the first to be offered the chance to compose the music for Rocky but had to turn it down because of prior commitments.[35] Avildsen reached out to Conti without any studio help because of the film's relatively low budget. Avildsen said, "The budget for the music was 25 grand. And that was for everything: The composer's fee, that was to pay the musicians, that was to rent the studio, that was to buy the tape that it was going to be recorded on."[36]

The main theme song, "Gonna Fly Now", made it to number one on Billboard magazine's Hot 100 list for one week (from July 2 to July 8, 1977) and the American Film Institute placed it 58th on its AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs.[37][38] United Artists Records released the soundtrack album on November 12, 1976.[39] EMI re-released the album on CD and cassette.[40]

Frank Stallone's song "Take You Back" is also on the soundtrack, and he also sings the song in the movie with other friends around a trash can fire.

Release

[edit]Theatrical

[edit]The movie began with two premieres in New York, starting with the world premiere for Rocky, which would take place at Paramount Theatre in New York City on Saturday, November 20, 1976, by United Artists and the other on the day after Sunday, November 21, 1976, by United Artists at Cinema II in New York City. The Los Angeles premiere took place at the Plaza in Westwood Village on December 1, 1976. This was then followed by a full official release on December 3, 1976, all throughout North America in the United States and Canada.[41]

Home media

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

- 1980 UK video release by Intervision Betamax, VHS (Rental Only)

- 1982 – CED Videodisc, Betamax and VHS; VHS release is rental only; 20th Century Fox Video release, Warner Home Video has rest of the World rights

- October 27, 1990 (VHS and LaserDisc)

- April 16, 1996 (VHS and LaserDisc)

- March 24, 1997 (DVD)

- April 24, 2001 (DVD, also packed with the Five-Disc Boxed Set)

- 2001 (VHS, 25th anniversary edition)

- December 14, 2004 (DVD, also packed with the Rocky Anthology box set)

- February 8, 2005 (DVD, also packed with the Rocky Anthology box set)

- December 5, 2006 (DVD and Blu-ray Disc – 2-Disc Collector's Edition, the DVD was the first version released by Fox and was also packed with the Rocky Anthology box set and the Blu-ray was the first version released by 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment)

- December 4, 2007 (DVD box set – Rocky The Complete Saga. This new set contains the new Rocky Balboa, but does not include the recent 2 disc Rocky. There are still no special features for Rocky II through Rocky V, although Rocky Balboa's DVD special features are all intact.)

- November 3, 2009 (Blu-ray box set – Rocky The Undisputed Collection. This release included six films in a box set. Previously, only the first film and Rocky Balboa were available on the format. Those two discs are identical to their individual releases, and the set also contains a disc of bonus material, new and old alike.[42])

- May 6, 2014 - Blu-ray re-release with an all new 4K remaster and the previous special features of the old release.[43]

- October 13, 2015 – Blu-ray box set, Rocky Heavyweight Collection 40th Anniversary Edition. All six films plus over three hours of bonus material, including the 4K remaster of the first film.[44]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Rocky grossed $5,488 on its opening day at Cinema II, a house record.[41] When it was released nationally, it grossed $5 million during its first wide weekend and consistently performed well for eight months[45] and eventually reached $117 million at the North American box office.[46] Adjusted for inflation in 2018, the film earned over $500 million in North America alone.[47] Overseas, Rocky grossed $107 million, for a worldwide box office total of $225 million.[48] With its production budget of just under $1 million, Rocky is notable for its worldwide percentage return of over 11,000 percent.[49] It was the highest-grossing film released in 1976 in the United States and Canada[50] and the second highest-grossing film of 1977, behind Star Wars.[51]

Critical response

[edit]Rocky received positive reviews at the time of its release. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave it 4 out of 4 stars and said that Stallone reminded him of "the young Marlon Brando."[52] Box Office Magazine claimed audiences would be "touting Sylvester 'Sly' Stallone as a new star".[53][54] Frank Rich liked the film, calling it "almost 100 per cent schmaltz", but favoring it over the cynicism that was prevalent in movies at that time, although he referred to the plot as "gimmicky" and the script "heavy-handed".[55] Several reviews, including Richard Eder's (as well as Canby's negative review), compared the work to that of Frank Capra.

The film did not escape criticism. Vincent Canby, of The New York Times, called it "pure '30s make believe" and dismissed both Stallone's acting and Avildsen's directing, calling the latter "none too decisive".[56] Andrew Sarris found the Capra comparisons disingenuous: "Capra's movies projected more despair deep down than a movie like Rocky could envisage, and most previous ring movies have been much more cynical about the fight scene"; commenting on Rocky's work for a loan shark, Sarris says the film "teeters on the edge of sentimentalizing gangsters". He found Meredith "oddly cast in the kind of part the late James Gleason used to pick his teeth".[57]

One of the positive online reviews came from the BBC Films website, with both reviewer Almar Haflidason and BBC online users giving it 5 out of 5 stars.[58]

The film enjoys a reputation as a classic and still receives nearly universal praise. On the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a 93% approval rating based on 75 reviews, with an average rating of 8.4/10. The site's critics consensus states: "This story of a down-on-his-luck boxer is thoroughly predictable, but Sylvester Stallone's script and stunning performance in the title role brush aside complaints."[59] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 70 out of 100, based on 14 critics, indicating "generally favorable" reviews.[60]

Accolades

[edit]Legacy

[edit]The Directors Guild of America awarded Rocky its annual award for best film of the year in 1976. Additionally, the Directors Guild voted Rocky as the 65th best-directed film of all time,[64] and in 2006, Sylvester Stallone's original screenplay for the film was selected by the Writers Guild of America as the 78th best screenplay of all time.[65] In a 2012 survey of members of the Motion Picture Editors Guild, Rocky was voted as one of the 75 best-edited films in all of cinema.[66]

In 2006, the Library of Congress selected Rocky for preservation in the United States National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant".[67][68]

In 1998, the American Film Institute (AFI) ranked Rocky as the 78th best film in American cinema.[69] The film's ranking rose to #57 on AFI's 10th anniversary edition of the list in 2007.[70] Additionally, in June 2008, AFI revealed its 10 Top 10—the best ten films in ten "classic" American film genres—after polling over 1,500 people from the creative community. Rocky was acknowledged as the second-best film in the sports genre, after Raging Bull.[71][72]

Film scholar Steven J. Schneider included Rocky in his book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, writing that the film is "often overlooked as schmaltz".[73] FilmSite.org, a subsidiary of American Movie Classics, included the film on their list of the 300 greatest films of all time.[74] Additionally, Films101.com ranked the film as the 228th best of all time.[75]

In 2006, British film magazine Total Film ranked Rocky at #71 on their list of the 100 greatest films of all time.[76] Based on their 2020 readers' poll, the film ranked #60 on Rolling Stone Australia's "100 Greatest Movies of All Time".[77] Additionally, Rolling Stone magazine ranked Rocky at #2 on their list of the 30 greatest sports films.[78]

In 2022, Esquire included the film on their list of "The 100 Best Movies of All Time".[79] Esquire also included both Rocky and its spinoff sequel Creed on their list of "The 30 Best Sports Movies of All Time".[80] In 2023, Slashfilm included Rocky on their list of the "Top 100 Movies of All Time", as voted by a selection of their writers and editors.[81] In 2024, entertainment news site Comic Book Resources ranked the film #23 on their list of the "55 Best Movies of All Time",[82] while Parade magazine ranked the film #45 on their list of the "100 Best Movies of All Time".[83]

In 2014, Rocky was ranked #95 by British film magazine Empire on their list of "The 301 Greatest Movies of All Time",[84] It was ranked #370 on their previous list of the 500 greatest films in 2008.[85] Conversely, in a 2005 poll by Empire, Rocky was No. 9 on their list of "The Top 10 Worst Pictures to Win Best Picture Oscar".[86]

In June 2014, The Hollywood Reporter compiled a list of the 100 best movies ever made, polling film industry insiders on their favorite films of all time.[87] Rocky ranked #91.[87] The following year The Hollywood Reporter polled hundreds of Academy members, asking them to re-vote on past controversial decisions. Academy members indicated that, given a second chance, they would award the 1977 Oscar for Best Picture to All the President's Men instead.[88]

Time Out ranked Rocky #1 on their list of the "50 Best Sports Movies of All Time".[89] On their list of "The 50 Greatest Sports Movies of All Time", entertainment news website Vulture ranked Rocky at #3.[90] In 2015, Thrillist compiled a list of "The 1001 Best Movies of All Time" by weighing ratings from IMDb, Rotten Tomatoes, Metacritic and Letterboxd. Rocky ranked #589.[91][92]

In 2021, the film ranked 2nd on ESPN's "Top 20 Sports Movies of All-Time".[93] In 2024, Forbes magazine ranked Rocky #1 on their list of "The 42 Greatest Sports Movies of All Time".[94]

British film site CinemaBlend ranked Rocky and Creed #1 and #17 respectively on their list of "The 25 Best Sports Movies".[95] On their list of "100 Best Movies of All Time", entertainment news website Collider ranked Rocky #94,[96] and on their list of "The 30 Greatest Sports Movies of All Time", Collider ranked the film #2.[97] On their list of the "Top 25 Sports Movies of All Time", entertainment news website MovieWeb ranked Rocky #4.[98] MovieWeb also ranked the film #3 on their list of the "20 Movies That Represent American Culture".[99]

On their list of "The 150 Best Sports Movies of All Time", Rotten Tomatoes ranked Rocky #17 and Creed #2.[100] Men's Health included Rocky on their list of the "50 of the Absolute Best Sports Movies Ever Made".[101] British GQ ranked the film #1 on their list of "The 22 Best Sports Movies".[102]

Year-end lists

[edit]Rocky has also appeared on several of the American Film Institute's 100 Years lists.

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (1998) – #78[69]

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills (2001) – #52

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Passions (2002) – Nominated[103]

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Heroes and Villains (2003)

- Rocky Balboa – #7 Hero[104]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs (2004)

- "Gonna Fly Now" – #58

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes (2005)

- "Yo, Adrian!" – #80[105]

- AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores (2005) – Nominated[106]

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Cheers (2006) – #4[107]

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) (2007) – #57[70]

- AFI's 10 Top 10 (2008) – #2 Sports Film[71]

Other media

[edit]Sequels

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

The film's success led to eight sequels, beginning with Rocky II in 1979. Followed by Rocky III in 1982, Rocky IV in 1985, Rocky V in 1990, Rocky Balboa in 2006, Creed in 2015 and Creed II in 2018. Another sequel, titled Creed III, was released in 2023; however, Stallone did not appear in the film.

Possible prequel

[edit]In July 2019, Stallone said in an interview that there have been ongoing discussions about a prequel to the original film based on the life of a young Rocky Balboa.[108]

Rocky Steps

[edit]The famous scene of Rocky running up the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art has become a cultural icon, with the steps acquiring the vernacular title of "Rocky Steps".[109] In 1982, a statue of Rocky, commissioned by Stallone for Rocky III, was placed at the top of the Rocky Steps. City Commerce Director Dick Doran claimed that Stallone and Rocky had done more for the city's image than "anyone since Ben Franklin".[110]

Differing opinions of the statue and its placement led to a relocation to the sidewalk outside the Spectrum Arena, although the statue was temporarily returned to the top of the steps in 1990 for Rocky V, and again in 2006 for the 30th anniversary of the original Rocky (although this time it was placed at the bottom of the steps). Later that year, it was moved permanently to a spot next to the steps.[110]

The scene is frequently parodied in other media. In the 2008 movie You Don't Mess with the Zohan, Zohan's nemesis, Phantom, goes through a parody training sequence finishing with him running up a desert dune and raising his hands in victory. In the fourth-season finale of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, as the credits roll at the end of the episode, Will is seen running up the steps at the Philadelphia Museum of Art; however, as he celebrates after finishing his climb, he passes out in exhaustion, and while he lies unconscious on the ground, a pickpocket steals his wallet and his wool hat. In The Nutty Professor, there is a scene where Sherman Klump (Eddie Murphy) struggles to, and eventually succeeds at, running up a lengthy flight of steps on his college campus, victoriously throwing punches at the top.

In 2006, E! named the "Rocky Steps" scene number 13 on its 101 Most Awesome Moments in Entertainment list.[111]

During the 1996 Summer Olympics torch relay, Philadelphia native Dawn Staley was chosen to run up the museum steps. In 2004, presidential candidate John Kerry ended his pre-convention campaign at the foot of the steps before going to Boston to accept his party's nomination for president.[112]

Novelization

[edit]Upon the film's release, a paperback novelization of the screenplay written by Rosalyn Drexler under the pseudonym Julia Sorel and published by Ballantine Books was released.[113][114]

Video games

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

Several video games have been produced based on the film. Rocky was released in 1987 for the Master System. Rocky was released in 2002 for the GameCube, Game Boy Advance, PlayStation 2, and Xbox, and a sequel, Rocky Legends, was released in 2004 for the PlayStation 2 and Xbox. In 2016, Tapinator released a mobile game named ROCKY for the iOS platform, with a planned 2017 release for Google Play and Amazon platforms.[115]

Musical

[edit]A musical was written by Stephen Flaherty and Lynn Ahrens (lyrics and music), with the book by Thomas Meehan, based on the film. The musical premiered in Hamburg, Germany in October 2012. It began performances at the Winter Garden Theater on Broadway on February 11, 2014, and officially opened on March 13, 2014.[116][117][118]

Documentaries

[edit]Rocky is featured in the 2017 documentary John G. Avildsen: King of the Underdogs about Academy Award-winning Rocky director John G. Avildsen, directed and produced by Derek Wayne Johnson.[119]

Stallone later hand-picked Johnson to direct and produce a documentary on the making of the original Rocky, entitled 40 Years of Rocky: The Birth of a Classic, which was released in 2020. The documentary features Stallone narrating behind-the-scenes footage from the making of the film.[120]

Parodies

[edit]Rocky has been parodied a lot over the years, even getting a feature length spoof called Ricky 1 in 1988. In 1986, Aki Kaurismaki, a Finnish director, made an 8-minute spoof of Rocky IV called "Rocky VI".

National Museum of American History

[edit]The red satin robe and black hat worn by Stallone in Rocky are featured in the National Museum of American History. Likewise, the red gloves worn by Stallone in Rocky II (1979), his white Nike boxing shoes, and striped boxing trunks from Rocky III (1981) are archived at the museum.[121] All items were on display for a temporary period following Stallone's donation in 2006, and have since been moved to the museum archives.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Rocky". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ "Rocky". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. Retrieved January 26, 2023.

- ^ "Film History of the 1970s". www.filmsite.org.

- ^ a b "Rocky". TCM database. Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ^ "Librarian Adds 25 Titles to Film Preservation List: National Film Registry 2006". Library of Congress.gov. Archived from the original on September 10, 2009. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ "Rocky, Fargo join National Film Registry". Reuters. December 28, 2006. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ "'Rocky Isn't Based on Me,' Says Stallone, 'But We Both Went the Distance'". The New York Times. November 1, 1976. Archived from the original on December 1, 2015. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ "Chuck Wepner finally recognized for 'Rocky' fame". ESPN. October 25, 2011. Archived from the original on September 13, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ a b Feuerzeig, Jeff (Director) (October 25, 2011). The Real Rocky (Motion picture). ESPN Films.

- ^ Ward, Tom. "The Amazing Story Of The Making Of 'Rocky'". Forbes. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Struby, Tim (September 21, 2005). "Marciano's career mark unique but flawed?". ESPN. Archived from the original on December 1, 2015. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ McRae, Donald (November 10, 2008). "Still smokin' over Ali but there's no time for hatred now". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 1, 2015. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ "Henry Winkler revealed how The Fonz saved Rocky". MeTV. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ Phil Jay (January 6, 2020). "Exclusive: Sylvester Stallone negotiations for Rocky movie uncovered". World Boxing News. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ Weisman, Aly (April 2, 2014). "Dirt-Poor Sylvester Stallone Turned Down $300,000 In 1976 To Ensure He Could Play 'Rocky'". Business Insider. Axel Springer SE. Archived from the original on December 1, 2015. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ Ward, Tom (August 29, 2017). "The Amazing Story Of The Making Of 'Rocky'". Forbes. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- ^ "The New York Times: Best Pictures".

- ^ a b Nashawaty, Chris (February 19, 2002). "EW: The Right Hook: How Rocky Nabbed Best Picture". Entertainment Weekly. p. 3. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ Neal Gabler, ReelThirteen, from WNET Archived June 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, February 22, 2014.

- ^ Block, Alex Ben; Wilson, Lucy Autrey, eds. (2010). George Lucas's Blockbusting: A Decade-By-Decade Survey of Timeless Movies Including Untold Secrets of Their Financial and Cultural Success. HarperCollins. p. 583. ISBN 978-0-06-177889-6.

The budget was $1,075,000 plus producer's fees of $100,000 ... The advertising costs were $4.2 million, slightly higher than the $4 million UA spent on ads for One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest in 1975.

- ^ Vellin, Bob (September 19, 2013). "Former heavyweight champion Ken Norton dies at 70". USA Today. Gannett Company. Archived from the original on December 2, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ McRae, Donald (November 11, 2008). "Still smokin' over Ali but there's no time for hatred now". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on December 1, 2015. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ^ "Czack, Sasha". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on August 3, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- ^ "Star Trek Database – Dorn, Michael". Star Trek Database. CBS Entertainment. Archived from the original on December 16, 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ^ "Stallone starts filming Rocky". History. A&E Networks. Archived from the original on December 2, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ "Rocky film locations". The Worldwide Guide To Movie Locations. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ "Stairway to Heaven". DGA. Archived from the original on October 24, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ "Steadicam 30th anniversary press release". Archived from the original on April 30, 2014.

- ^ Neuwirth, Aaron (November 26, 2015). "Movie Trivia Thursday (Nov. 26): 5 Cool Facts About 5 Classic Boxing Films". RantHollywood. Archived from the original on June 20, 2016. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ^ Merron, Jeff. "Reel Life: 'Rocky'". ESPN. Archived from the original on December 2, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ "72 Hard-Hitting Facts About the 'Rocky' Movies". Yahoo.com. November 24, 2015. Archived from the original on November 27, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ "Stallone Corrects ROCKY's Most Famous 'Mistake'". Screen Rant. October 16, 2018. Archived from the original on February 4, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ "Don't Be a Bum, Check Out These 10 'Rocky' Facts". Screencrush.com. November 23, 2015. Archived from the original on January 29, 2017. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ "Bill Conti Interview". Emmy TV Legends. Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Foundation. September 20, 2010. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ^ Armstrong, Lois (March 21, 1977). "Rocky's Talia Shire Says the Song Is You to Her Composer Husband, David Shire". People. 7 (11). Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ^ McQuade, Dan (March 13, 2014). "Director John G. Avildsen Told Stallone to Lose Weight Before Filming Rocky". Philadelphia. Metrocorp. Archived from the original on November 29, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ^ "Popculturemadness.com list of 1977 number ones, based on Billboards lists". July 8, 1977. Archived from the original on September 6, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2006.

- ^ "AFI 100 songs". June 22, 2004. Archived from the original on October 4, 2006. Retrieved October 14, 2006.

- ^ "Motion Pictures January–June 1976: Third Series, Parts 12–13". Catalog of Copyright Entries. 30 (1). The Library of Congress. 1977. ISSN 0090-8371.

- ^ "Rocky (Original Motion Picture)". AllMusic. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "'Network,' $49,721, Sutton; N.Y. Slow Ahead of Turkey Day; 'Tycoon' Posts Sinewy $45,000". Variety. November 24, 1976. p. 10.

- ^ "MGM Preparing Rocky Collection on Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on December 12, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

- ^ Rocky Blu-ray Release Date May 6, 2014, archived from the original on June 11, 2020, retrieved February 15, 2021

- ^ "Rocky: Heavyweight Collection". Amazon. Archived from the original on July 17, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ Murphy, A.D. (July 13, 1977). "June Key City Dom. B.O. Wow With Estimated $66 mil". Daily Variety. p. 1.

- ^ "Rocky (1976)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on July 26, 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ Austin, Christina (November 30, 2015). "'Creed' Has a Long Way to Go to Beat 'Rocky' at the Box Office". Fortune. Time, Inc. Archived from the original on December 1, 2015. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ Hall, Sheldon; Neale, Stephen (2010). Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-8143-3008-1.

Rocky was the "sleeper of the decade". Produced by UA and costing just under $1 million, it went on to earn a box-office gross of $117,235,247 in the United States and $225 million worldwide.

- ^ Crowley, Julian (April 4, 2011). "10 Most Profitable Low Budget Movies of All Time". Business Pundit. Aven Enterprises. Archived from the original on December 1, 2015. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ "1976 Box Office". WorldwideBoxoffice.com. Archived from the original on December 2, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1977". Variety. January 4, 1978. p. 21.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1977). "Rocky Movie Review & Film Summary". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 18, 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2017 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ "Box Office Magazine Rocky Review". November 22, 1976. Archived from the original on November 23, 2005. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ "Arizona Daily Star Review". Archived from the original on May 28, 2007. Retrieved November 14, 2006.

- ^ Frank Rich. New York Post November 22, 1976. p. 18

- ^ Canby, Vincent (November 22, 1976). "Film: 'Rocky,' Pure 30's Make-Believe". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2006. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ The Village Voice November 22, 1976, p.61

- ^ "Rocky @ BBC Films". Archived from the original on September 1, 2006. Retrieved November 14, 2006.

- ^ "Rocky". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2022.

- ^ "Rocky Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ^ "The 49th Academy Awards (1977) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ "Film in 1978". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- ^ "Winners & Nominees 1977". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- ^ The 80 Best-Directed Films Directors Guild of America. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ The 101 Best Screenplays Writers Guild of America West. Retrieved October 11, 2024.

- ^ The 75 Best Edited Films Editors Guild Magazine (Vol. 1, Issue 3) via Internet Archive. Published May 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ "Librarian Adds 25 Titles to Film Preservation List: National Film Registry 2006". Library of Congress.gov. Archived from the original on September 10, 2009. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ "Rocky, Fargo join National Film Registry". Reuters. December 28, 2006. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ a b "The 100 Greatest American Films". American Film Institute. 1998. Archived from the original on August 21, 2006. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

- ^ a b The 100 Greatest American Films — 10th Anniversary Edition American Film Institute. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- ^ a b "Top 10 Sports Films". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 10, 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "AFI Crowns Top 10 Films in 10 Classic Genres". ComingSoon.net. June 17, 2008. Archived from the original on August 18, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ Schneider, Stephen Jay (2005). 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die (Revised ed.). London, England: New Burlington Books. p. 615. ISBN 978-0-7641-5907-7.

- ^ The Third 100 Greatest Films AMC's FilmSite. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ The Best Movies of All Time (10,267 Most Notable) Films101.com via Internet Archive. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ Total Film: Top 100 Movies Total Film. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ 100 Greatest Movies of All Time Rolling Stone Australia. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ 30 Best Sports Movies of All Time Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ The 100 Best Movies of All Time Esquire. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ The Best Sports Movies of All Time Esquire. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ /Film's Top 100 Movies of All Time /Film. Retrieved August 31, 2024.

- ^ The 55 Best Movies of All Time, Ranked Comic Book Resources. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ The 100 Best Movies of All Time Parade. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ "The 301 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- ^ "Empire's The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ "Mel Gibson's "Braveheart" Voted Worst Oscar Winner". hollywood.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013.

- ^ a b Hollywood’s 100 Favorite Films The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ "Recount! Oscar Voters Today Would Make 'Brokeback Mountain' Best Picture Over 'Crash'". The Hollywood Reporter. February 18, 2015. Archived from the original on January 22, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ The Best Sports Movies of All Time, from 'Field of Dreams' to 'Creed' Time Out. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ The 50 Greatest Sports Movies of All Time Vulture. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ The Definitive Ranking of the 1,001 Best Movies Ever Thrillist. Retrieved October 22, 2024.

- ^ 2015 Edition: Top10ner's 1001 'Greatest' Movies of All Time IMDb. Retrieved October 22, 2024.

- ^ Top 20 Sports Movies of All-Time ESPN. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ The 42 Greatest Sports Movies of All Time Forbes. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ The 25 Best Sports Movies CinemaBlend. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ Collider's 100 Best Movies of All Time, Ranked — 100 Through 81 Collider. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ The 30 Best Sports Movies of All Time, Ranked Collider. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ Top 25 Sports Movies of All Time, Ranked MovieWeb. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ 20 Movies That Represent American Culture MovieWeb. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ 150 Best Sports Movies of All Time Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ 50 of the Absolute Best Sports Movies Ever Made Men's Health. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ The 22 Best Sports Movies, Ranked British GQ. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ AFI's 100 Years... 100 Passions: America’s Greatest Love Stories – The 400 Nominated Films American Film Institute via Internet Archive. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- ^ "AFI 100 Heroes and Villains". Archived from the original on October 4, 2006. Retrieved October 11, 2006.

- ^ "AFI 100 Quotes". 2005. Archived from the original on September 6, 2006. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- ^ AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores: Honoring America’s Greatest Film Music, Official Ballot American Film Institute via Internet Archive. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- ^ "AFI 100 Cheers". June 14, 2006. Archived from the original on August 20, 2006. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

- ^ "Sylvester Stallone Reveals 'Rocky' Sequel and Prequel Are in Development". popculture.com. July 16, 2019. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ Holzman, Laura. "Rocky". Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities. Archived from the original on December 2, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Avery, Ron. "Rocky Statue". UShistory.org. Independence Hall Association. Archived from the original on January 10, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ "E! Channel's 101 Most Awesome Moments in Entertainment". Archived from the original on January 18, 2006. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ "Philly.com". Archived from the original on December 17, 2004. Retrieved November 16, 2006.

- ^ Rocky (Book, 1976). WorldCat.org. OCLC 2851748.

- ^ Sorel, Julia (1976). Rocky. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25321-3.

- ^ Grubb, Jeff (December 8, 2016). "Rocky Says 'Yo, Adrian' to the Mobile Gaming Market". Fortune Magazine. Archived from the original on December 29, 2016. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth. "Rocky the Musical Makes World Premiere in Germany Nov. 18; American Drew Sarich Stars" Archived November 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine November 18, 2012

- ^ Hetrick, Adam "Rocky the Musical Will Play Broadway's Winter Garden Theatre in 2014" Archived August 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine April 28, 2013

- ^ Official: ROCKY to Open at Winter Garden Theatre on 3/13; Previews Begin 2/11 Archived September 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Broadway World, Retrieved September 22, 2013

- ^ Kreps, Daniel. "John G. Avildsen, 'Rocky,' 'The Karate Kid' Director, Dead at 81" Archived April 15, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Rolling Stone, San Francisco, CA, June 17, 2017. Retrieved on August 21, 2018.

- ^ Drown, Michelle. "John G. Avildsen: King of the Underdogs Director Derek Wayne Johnson" Archived July 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The Santa Barbara Independent, Santa Barbara, CA, January 26, 2017. Retrieved on February 16, 2017.

- ^ "Collections Search Results". National Museum of American History. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Rocky at IMDb

- Rocky at the TCM Movie Database

- Rocky at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Making of Rocky by Sylvester Stallone

- A Movie of Blood, Spit and Tears by Royce Webb

- Six Little Known Truths about Rocky by Ralph Wiley

- Which Rocky is the real champ? by Bill Simmons

- Rocky: Behind the Scenes