| Wings | |

|---|---|

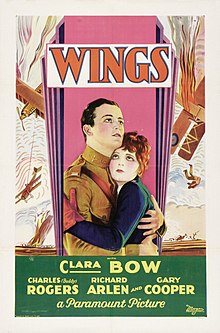

Film poster | |

| Directed by | William A. Wellman |

| Written by | Titles: Julian Johnson |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by | John Monk Saunders |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Harry Perry |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | J.S. Zamecnik (uncredited) |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Famous Lasky Corporation |

Release dates |

|

Running time | |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $2 million[4] |

| Box office | $3.8 million (US and Canada rentals)[5] |

Wings is a 1927 American silent and synchronized sound film which won the first Academy Award for Best Picture. While the sound version of the film has no audible dialogue, it was released with a synchronized musical score with sound effects. The original soundtrack to the sound version is preserved at UCLA.[6]

The film stars Clara Bow, Charles "Buddy" Rogers, and Richard Arlen. Rogers and Arlen portray World War I combat pilots in a romantic rivalry over a woman. It was produced by Lucien Hubbard, directed by William A. Wellman, and released by Paramount Famous Lasky Corporation. Gary Cooper appears in a small role, which helped launch his career in Hollywood.

The film, a romantic action-war picture, was rewritten by scriptwriters Hope Loring and Louis D. Lighton from a story by John Monk Saunders to accommodate Bow, Paramount's biggest star at the time. Wellman was hired, as he was the only director in Hollywood at the time who had World War I combat pilot experience, although Richard Arlen and John Monk Saunders had also served in the war as military aviators. The film was shot on location on a budget of $2 million (equivalent to $34.42 million in 2023) at Kelly Field in San Antonio, between September 7, 1926, and April 7, 1927. Hundreds of extras and some 300 pilots were involved in the filming, including pilots and planes of the United States Army Air Corps which were brought in for the filming and to provide assistance and supervision. Wellman extensively rehearsed the scenes for the Battle of Saint-Mihiel over ten days with some 3,500 infantrymen on a battlefield made for the production on location. Although the cast and crew had much spare time during the filming because of weather delays, shooting conditions were intense, and Wellman frequently conflicted with the military officers brought in to supervise the picture.

Acclaimed for its technical prowess and realism upon release, the film became the yardstick against which future aviation films were measured, mainly because of its realistic air-combat sequences. It went on to win the inaugural Academy Award for Outstanding Picture at the first Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences award ceremony in 1929,[7] the only fully silent film to do so.[b] It also won the Academy Award for Best Engineering Effects (Roy Pomeroy). Wings was one of the first widely released films to show nudity. In 1997, Wings was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant", and the film was re-released to Cinemark theaters to coincide with the 85th anniversary for a limited run in May 2012. The film was re-released again for its 90th anniversary in 2017. The Academy Film Archive preserved Wings in 2002.

The film entered the public domain in the United States in 2023.[8]

Plot

[edit]

Jack Powell and David Armstrong are rivals in the same small American town, both vying for the attentions of pretty Sylvia Lewis. Jack fails to realize that "the girl next door", Mary Preston, is desperately in love with him. The two young men both enlist to become combat pilots in the Army Air Service. When they leave for training camp, Jack mistakenly believes Sylvia prefers him, but she actually prefers David and lets him know about her feelings, but is too kindhearted to turn down Jack's affection.

The two men endure a rigorous training period, where they are enemies. But during a bloody boxing match, they realize each other's courage and become best friends. Upon graduating, they are sent to France to fight against Imperial Germany.

Jack and David are billeted together. Their tent mate is Cadet White, but their acquaintance is all too brief; White is killed in an air crash the same day.

Mary joins the war effort by becoming an ambulance driver. She later learns of Jack's reputation as the ace known as "The Shooting Star" and encounters him while on leave in Paris. She finds him, but he is too drunk to recognize her. She takes him back to his room and puts him to bed, but when two military police barge-in while she is innocently changing from a borrowed dress back into her uniform in the same room, she is forced to resign and return to the United States.

The climax of the story comes with the epic Battle of Saint-Mihiel. David is shot down and presumed dead. However, he survives the crash landing, steals a German biplane, and heads for the Allied lines. By a tragic stroke of bad luck, Jack spots the enemy aircraft and, bent on avenging his friend, begins an attack. He is successful in downing the aircraft and lands to retrieve a souvenir of his victory. The owner of the land where David's aircraft crashed urges Jack to come to the dying man's side. He agrees and becomes distraught when he realizes what he has done. David consoles him, and before he dies, forgives his comrade.

At the war's end, Jack returns home to a hero's welcome. He visits David's grieving parents to return his friend's effects. During the visit, he begs their forgiveness for causing David's death. Mrs. Armstrong says it is not Jack who is responsible for her son's death, but the war. Then, Jack is reunited with Mary and realizes he loves her.

Cast

[edit]- Clara Bow as Mary Preston

- Charles "Buddy" Rogers as Jack Powell

- Richard Arlen as David Armstrong

- Jobyna Ralston as Sylvia Lewis

- El Brendel as Herman Schwimpf

- Richard Tucker as Air Commander

- Gary Cooper as Cadet White

- Gunboat Smith as Sergeant

- Henry B. Walthall as Mr. Armstrong

- Roscoe Karns as Lieutenant Cameron

- Julia Swayne Gordon as Mrs. Armstrong

- Arlette Marchal as Celeste

| George Irving | Mr. Powell |

|---|---|

| Hedda Hopper | Mrs. Powell |

| Evelyn Selbie | dressing room attendant |

| Robert Livingston | recruit in examination office |

| William A. Wellman | doughboy |

| Nigel De Brulier | French peasant |

| Zalla Zarana | French peasant girl |

| Douglas Haig | little French boy |

| Thomas Carrigan | aviator |

| Charles Barton | soldier flirting with Mary |

| James Pierce | military policeman |

| Carl von Haartman | German officer |

| Thomas Carr | aviator |

| Dick Grace | aviator |

Music

[edit]The film featured a theme song entitled "Wings" which was composed by J. S Zamecnik and Ballard Macdonald. [9]

Production

[edit]Script and experience

[edit]

The film was written by John Monk Saunders (with uncredited story ideas contributed by Byron Morgan), Hope Loring and Louis D. Lighton (screenplay), produced by Lucien Hubbard (who also did uncredited co-editing), directed by William A. Wellman, with an original orchestral score by J.S. Zamecnik, which was also uncredited. It was rewritten to accommodate Clara Bow, as she was Paramount's biggest star, but she wasn't happy about her part: "Wings is...a man's picture and I'm just the whipped cream on top of the pie".[10]

Producers Lucien Hubbard and Jesse L. Lasky hired director Wellman as he was the only director in Hollywood at the time who had World War I combat pilot experience.[11][12] Actor Richard Arlen and writer John Monk Saunders had also served in World War I as military aviators. Arlen was able to do his own flying in the film and Rogers, a non-pilot, underwent flight training during the course of the production, so that, like Arlen, Rogers could also be filmed in closeup in the air. Lucien Hubbard offered flying lessons to all, and despite the number of aircraft in the air, only two incidents occurred—one involved stunt pilot Dick Grace, who broke his neck falling out of the cockpit after a controlled crash;[13] while the other was the fatal crash of an Army Air Service pilot.[14] Wellman was able to attract War Department support and involvement in the project, and displayed considerable prowess and confidence in dealing with planes and pilots onscreen, knowing "exactly what he wanted", bringing with it a "no-nonsense attitude" according to military film historian Lawrence H. Suid.[15]

Filming

[edit]Aerial and battle sequences

[edit]

Wings was shot and completed on a budget of $2 million at Kelly Field, San Antonio, Texas between September 7, 1926, and April 7, 1927.[12] Primary scout aircraft flown in the film were Thomas-Morse MB-3s standing in for American-flown SPADs and Curtiss P-1 Hawks painted in German livery. Developing the techniques needed for filming closeups of the pilots in the air and capturing the speed and motion of the planes onscreen took time, and little usable footage was produced in the first two months.[16] Wellman soon realized that Kelly Field did not have the adequate numbers of planes or skilled pilots to perform the needed aerial maneuvers, and he had to request technical assistance and a supply of planes and pilots from Washington. The Air Corps sent six planes and pilots from the 1st Pursuit Group stationed at Selfridge Field near Detroit, including then-2nd Lt. Elmer J. Rogers Jr. and 2d Lt. Clarence S. "Bill" Irvine who became Wellman's adviser. Irvine was responsible for engineering an airborne camera system to provide close-ups and for the planning of the dogfights, and when one of the pilots broke his neck, performed in one of the battle scenes himself.[14][16][c]

Hundreds of extras were brought in to shoot the picture, and some 300 pilots were involved in the filming.[17] Because the aerial battles required ideal weather to shoot, the production team had to wait on one occasion for 18 consecutive days for proper conditions in San Antonio.[12] If possible, Wellman attempted to capture footage in the air in contrast to clouds in the background, above or in front of cloud banks to generate a sense of velocity and danger. Wellman later explained, "motion on the screen is a relative thing. A horse runs on the ground or leaps over fencers or streams. We know he is going rapidly because of his relation to the immobile ground".[16] Against the clouds, Wellman enabled the planes to "dart at each other", and to "swoop down and disappear in the clouds", and to give the audience the sense of the disabled planes plummeting. During the delay in the aerial shooting, Wellman extensively rehearsed the scenes for the Battle of Saint-Mihiel over ten days with some 3500 infantrymen.[18] A large battlefield with trenches and barbed wire was created on location for the filming. Wellman took responsibility for the meticulously planned explosions himself, detonating them at the right time from his control panel.[18] According to Peter Hopkinson, at least 20 young men, including cameraman William Clothier, were given hand-held cameras to film "anything and everything" during the filming.[19]

Wellman frequently conflicted with the military officers brought in to supervise the picture, especially the infantry commander whom he considered to have "two monumental hatreds: fliers and movie people". After one argument Wellman retorted to the commander, "You're just a goddamn fool because the government has told me you have to give me all your men and do just exactly what I want you to do."[16] Although Wellman paid much attention to technical details in shooting, he used cars and clothing of the year during the filming, forgetting to use those of World War I.[20] He took six weeks to fully edit the film and prepare it for release.[21]

Cast exploits

[edit]

Whereas most Hollywood productions of the day took little more than a month to shoot, Wings took approximately nine months to complete in total. Although Wellman was generating spectacular aerial footage and making Hollywood film history, Paramount expressed concerns with the cost of production and expanding budget. They sent an executive to San Antonio to complain to Wellman who swiftly told him that he had two options, "a trip home or a trip to the hospital".[18] According to biographer Frank T. Thompson, Wellman approached producer David O. Selznick regarding a contract predicament asking him what he should do to which Selznick replied, "Just keep your mouth shut. You've got 'em where it hurts."[21] Otto Kahn, the financier bankrolling the production, arrived on set as Wellman was filming the St-Mihiel battle sequence, inadvertently disrupted Wellman's detonation timings, and caused several extras to be seriously injured. Wellman loudly and profanely ordered Kahn off the set. That evening, Kahn visited Wellman in his hotel room, told him he was impressed with his direction, and he could have whatever he needed to finish the picture.[13]

The cast and crew had a lot of time on their hands between shooting sequences, and according to director Wellman, "San Antonio became the Armageddon of a magnificent sexual Donnybrook". He recalled that they stayed at the Saint Anthony Hotel for nine months and by the time they left the elevator girls were all pregnant.[12] He stated that Clara Bow openly flirted with the male cast members and several of the pilots which was reciprocated, despite having become engaged to Victor Fleming the day after arriving in San Antonio on September 16, 1926.[22] Gary Cooper, appearing in a role which helped launch his career in Hollywood, began a tumultuous affair during the production with Bow.[23] Cooper reportedly showed Howard Hughes the script to the film and he was not impressed, considering the drama in it to be "sudsy", although he informed Cooper that he looked forward to seeing how Wellman would accomplish the technical aerial sequences.[23] Bow strongly detested the wardrobe that Paramount designer Travis Banton made for the film. She slit the necklines and cut off the sleeves of her costumes, much to Banton's chagrin.[24]

Notable scenes

[edit]

Wings is also one of the first widely released films to show nudity. In the enlistment office, nude men are visible from behind undergoing physical exams, through a door which opens and closes several times.[25] In the scene in which Rogers becomes drunk, the intoxication displayed on screen was genuine, as although 22 years of age, he had never tasted liquor before, and quickly became inebriated from drinking champagne.[26] During David's death scene, Jack is plainly observed kissing him on the left cheek near the left corner of Dave's mouth, which has led to interpretations of this film as depicting cinema's first LGBT male-to-male kiss.[27][28] While there is no general consensus about which film achieves this LGBT milestone, D.W. Griffith's Intolerance (1916), Cecil B. DeMille's Manslaughter (1922), and Josef von Sternberg's Morocco (1930) have also been suggested.[29][30]

Release and reception

[edit]

Wellman dedicated the film "to those young warriors of the sky whose wings are folded about them forever".[20] A sneak preview was shown May 19, 1927, at the Texas Theater on Houston Street in San Antonio. The premiere was held at the Criterion Theater, in New York City, on August 12, 1927, and was screened for 63 weeks before being moved to second-run theaters.[31] The film eventually opened in Los Angeles on January 15, 1928. The original Paramount release of Wings was color tinted and had some sequences in an early widescreen process known as Magnascope, also used in the 1926 Paramount film Old Ironsides. The original release also had the aerial scenes use the Handschiegl color process for flames and explosions. Late in 1928, a sound version was prepared with synchronized sound effects and music, using the General Electric Kinegraphone (later RCA Photophone) sound-on-film process.[4]

Wings was an immediate success upon release and became the yardstick against which successive aviation films were measured for years thereafter, in terms of "authenticity of combat and scope of production".[20] One of the reasons for its resounding popularity was the public infatuation with aviation in the wake of Charles Lindbergh's transatlantic flight.[32] The Air Corps who had supervised production expressed satisfaction with the end product.[20] The critical response was equally enthusiastic and the film was widely praised for its realism and technical prowess, despite a superficial plot, "an aviation picnic" as Gene Brown called it.[33][34] The combat scenes of the film were so realistic that one writer studying the film in the early 1970s was wondering if Wellman had used actual imagery of planes crashing to earth during World War I.[35] One critic observed: "The exceptional quality of Wings lies in its appeal as a spectacle and as a picture of at least some of the actualities of flying under wartime conditions."[20] Another wrote: "Nothing in the line of war pictures ever has packed a greater proportion of real thrills into an equal footage. As a spectacle, Wings is a technical triumph. It piles punch upon punch until the spectator is almost nervously exhausted".[35] Mordaunt Hall of The New York Times praised the cinematography of the flying scenes and the direction and acting of the entire cast in his review dated August 13, 1927. Hall notes only two criticisms, one slight on Richard Arlen's performance and of the ending, which he described as "like so many screen stories, much too sentimental, and there is far more of it than one wants."[36]

By June 1932, Wings had earned $3.6 million in worldwide theatrical rentals.[37]

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a score of 93% based on 61 reviews, with an average rating of 7.6/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "Subsequent war epics may have borrowed heavily from the original Best Picture winner, but they've all lacked Clara Bow's luminous screen presence and William Wellman's deft direction."[38]

Accolades

[edit]On May 16, 1929, the first Academy Award ceremony was held at the Hotel Roosevelt in Hollywood to honor outstanding film achievements of 1927–1928. Wings was entered in a number of categories and was the first film to win the Academy Award for Best Picture (then called "Best Picture, Production") and Best Engineering Effects for Roy Pomeroy for the year. It remains the only silent film to win Best Picture.

Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, which won Unique and Artistic Production, was considered an equal top winner of the night but the following year, the Academy dropped the Unique and Artistic Production award and decided retroactively that the award won by Wings was the highest honor that could be awarded.[39] The statuette, not yet known as the "Oscar", was presented by Douglas Fairbanks to Clara Bow on behalf of the producers, Adolph Zukor and B.P. Schulberg.[40]

Legacy

[edit]The Cross and Cockade, a World War I pilots association, decided to host a tribute to Wings in 1968. They found Paramount did not even have photos. They recreated stock film, reprinted the picture and had a retrospective inviting the director and stars Richard Arlen and Buddy Rogers. The brochure was available for a small period of years but is reprinted in a book narrated by Richard Arlen, published by Judy Watson, titled Wings and other Recollections of Early Hollywood ISBN 1507552386 and LCCN 2015-900786.

For many years, Wings was considered a lost film until a print was found in the Cinémathèque Française film archive in Paris and quickly copied from nitrate film to safety film stock.[4][41] It was again shown in theaters, including some theaters where the film was accompanied by Wurlitzer pipe organs.[42]

In retrospect, film scholar Scott Eyman in his 1997 book The Speed of Sound: Hollywood and the Talkie Revolution 1926–1930 highlights both the diverse structure and adapted aspects of Wings in that transitional period in American cinematography:

Ironically, a mass-market silent spectacular like William Wellman's Wings effortlessly showcases far more visual variety than mainstream American films have offered since: it displays shifts from brutal realism to nonrealistic techniques associated with Soviet avant-garde or impressionistic French cinema – double exposures, subjective point-of-view shots, trick effects, symbolic illustrations on the titles, and so on.[43]

In 1997, Wings was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[44][45][46] In 2006, director Wellman's son, William Wellman Jr., authored a book about the film and his father's participation in the making of it, titled The Man and His Wings: William A. Wellman and the Making of the First Best Picture.[47]

The film was the focus of an episode of the television series Petticoat Junction that originally aired November 9, 1968, the show's sixth season. Arlen and Rogers were scheduled to appear during the film's opening at one of the local cinemas in 1928. They opted instead to attend the New York screening that was held the same night. Uncle Joe writes a letter chiding the pair for forsaking the town. To atone and generate publicity, they agreed to attend a second opening, 40 years later. This episode features actual clips from the movie.[48][49]

Arlen and Rogers also appeared together as themselves on a December 18, 1967, episode of The Lucy Show titled "Lucy and Carol Burnett: Part 2". They are introduced as the stars of Wings at a ceremony to mark the graduation of Lucille Ball and Carol Burnett from stewardess training. They appear on stage beneath stills taken from the film and later in the ceremony, star in a musical with Ball and Burnett, as two World War I pilots.[50]

Restoration

[edit]As the original negatives are lost, the closest to an original copy is a spare negative rediscovered in Paramount's vaults subsequent to the Cinémathèque Française print. Suffering from decay and defects, the negative was fully restored with modern technology. The original synchronized soundtrack to the sound version survives at UCLA.[6] For the restored version of Wings, it was decided not to use the original, now public-domain, synchronized score so that a new modern soundtrack could be used. The original music score was re-orchestrated. The sound effects were recreated at Skywalker Sound using archived audio tracks. The scenes using the Handschiegl color process were also recreated for the restored version.[51]

The first restored version was released on Laserdisc in the US in 1985, was one of the earliest discs with digital sound, and featured an organ score by Gaylord Carter. This version would be released in a double feature with The Big Parade for its Japanese Laserdisc release.

In 1996, Paramount issued a VHS release.[52] In 2012, the company issued a "meticulously restored" version for DVD and Blu-ray.[51] The remastered version in high definition coincided with the centennial anniversary of Paramount. It opens with a logo montage, which starts with the 2010–2013 version of the previous logo or the 2011–2012 "100 Years" version of the current logo and looks back at previous logos from the past 100 years, starting with the 1990 version of the 1986 logo, up into the opening logo of the film.[51] On May 2 and 16, 2012, select Cinemark theaters screened an exclusive limited re-release twice daily to coincide with the film's 85th anniversary. It received a worldwide limited release for its 90th anniversary celebration.[53][54]

The film was preserved by the Academy Film Archive, in conjunction with the Library of Congress and Paramount Pictures, in 2002.[55]

The sound version of the film was created late in 1928 due to the public's apathy towards silent films and therefore this was the version that most audiences saw back in 1928 and 1929. Even though the original synchronized soundtrack survives at UCLA it has not yet been restored to the film and released.

See also

[edit]- List of early sound feature films (1926–1929)

- List of rediscovered films

- The House That Shadows Built (1931 promotional film by Paramount)

- "Wings" (1927 film score)

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ William Wellman on production of Wings in episode Hollywood Goes to War where he stated Otto Kahn was a financier on Wings visiting the production on location in Texas

- ^ The 2011 winner The Artist, mostly silent but with synchronized sound, contained recorded dialogue at the end.

- ^ Primary stunt pilot Dick Grace broke his neck when an aircraft supposed to flip over after being shot down on takeoff failed to do so.[14]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Brownlow, Kevin and David Gill, Hollywood: A Celebration of American Silent Film (13-part television documentary series). New York: HBO Home Video, 1980.

- ^ "WINGS (A)". Famous Lasky Film Service. British Board of Film Classification. January 12, 1928. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- ^ "WINGS (PG)". Paramount Pictures. British Board of Film Classification. February 22, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c Bennett, Carl. "Progressive Silent Film List: Wings". Silent Era. 2012. Retrieved: February 27, 2012.

- ^ Cohn, Lawrence (October 15, 1990). "All Time Film Rental Champs". Variety. p. M-194. ISSN 0042-2738.

- ^ a b "Wings / Paramount Famous Lasky Corp". library.ucla.edu.

- ^ "Dorothy Wellman dies at 95". Variety. September 17, 2009. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ^ "Preserved Projects". Academy Film Archive.

- ^ "Wings". Brown Digital Repository. Retrieved January 6, 2025.

- ^ Porter 2005, p. 148.

- ^ Wellman, William Jr. (March–April 1970). "William Wellman: Rebel Director". Action. Vol. 5, no. 2. Directors Guild of America. pp. 13–15.

- ^ a b c d Stenn 2000, p. 73.

- ^ a b "Hollywood Goes to War". Hollywood. January 29, 1980. 36:24 minutes in. Retrieved October 30, 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c Lusier, Tim (2004). "Daredevils in the Air: Three of the Greats, Wilson, Locklear and Grace". SilentsAreGolden. Archived from the original on December 28, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ^ Suid 2002, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d Suid 2002, p. 36.

- ^ Farmer 2006, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Suid 2002, p. 37.

- ^ Hopkinson 2007, p. 217.

- ^ a b c d e Suid 2002, p. 39.

- ^ a b Thompson 1983, p. 72.

- ^ Stenn 2000, p. 73-4.

- ^ a b Porter 2005, p. 147.

- ^ Stenn 2000, p. 75.

- ^ Mast 1986, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Stenn 2000, p. 74.

- ^ Russo, Vito (1981). The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-06-337019-7. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ "Before Brokeback: The First Same-Sex Kiss in Cinema (1927)". Open Culture. January 26, 2012.

- ^ Strike, Karen (October 16, 2016). "The First Same-Sex Kiss in Cinema (1916)". Flashbak. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ Monteil, Abby (October 14, 2021). "A history of LGBTQ+ representation in film". Stacker. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ Thompson 2002, p. 25.

- ^ Farmer 2006, p. 14.

- ^ Suid 2002, p. 28-39.

- ^ Brown 1984, p. 4-5.

- ^ a b Suid 2002, p. 38.

- ^ Hall, Mourdant (August 13, 1927). "The Screen: The Flying Fighters". The New York Times. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ^ "Big Sound Grosses". Variety. New York. June 21, 1932. p. 62.

- ^ "Wings". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ "The 1st Academy Awards (1929) Nominees and Winners". AMPAS. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ^ Stenn 2000, p. 159.

- ^ "Silent Oscar winner Wings out for anniversary". Euronews. January 19, 2012. Archived from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ^ "Datebook" magazine, San Francisco Chronicle.[full citation needed]

- ^ Eyman 1997, p. 220.

- ^ The Code of Federal Regulations of the United States of America. US Government Printing Office. 1999. p. 93.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress: National Film Preservation Board. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ "New to the National Film Registry". Library of Congress. December 1997. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ Wellman 2006.

- ^ Petticoat Junction; Season 6, Episode 6: Wings. Retrieved October 30, 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ Humphrey, Hal (October 25, 1968). "Out of the Air: Buddy Rogers–47 Years Later". East Liverpool Review. p. 15. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ The Lucy Show – Episode: Lucy Becomes an Airline Stewardess Pt 2. December 18, 1967. Archived from the original on May 11, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2013 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c "Paramount Home Entertainment proudly presents the very first Best Picture Academy Award® Winner on Blu-ray™ and DVD for the first time ever-Wings". Paramount Home Entertainment. November 15, 2011. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ^ Wings. Wings VHS. ASIN 6300215482.

- ^ "Oscar-winning silent film returns to cinemas work". BBC News. May 3, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ^ Beggs, Scott (May 2, 2012). "'Wings,' The First Best Picture Winner to Hit Big Screens Again". Film School Rejects. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ "Preserved Projects". Academy Film Archive.

Bibliography

[edit]- Brown, Gene (1984). The New York Times Encyclopedia of Film: 1896–1928. Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8129-1046-9.

- Brownlow, Kevin (1968). The Parade's Gone by. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03068-8.

- Danesi, Marcel (2013). The History of the Kiss: The Birth of Popular Culture. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-37685-5.

- Dolan, Edward F. (1985). Hollywood Goes to War. Hamlyn. ISBN 978-0-600-50053-7.

- Eyman, Scott (1997). The Speed of Sound: Hollywood and the Talkie Revolution 1926-1930. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-0428-6.

- Farmer, Jim (November 2006). "The Making of Flyboys". Air Classics. Vol. 42, no. 11.

- Hardwick, Jack; Schnepf, Ed (1989). A Viewer's Guide to Aviation Movies: The Making of the Great Aviation Films. General Aviation Series. Vol. 2. Challenge Publications.

- Hopkinson, Peter (2007). Screen of Change. UKA Press. ISBN 978-1-905796-12-0.

- Mast, Gerald (1986). The Movies in Our Midst: Documents in the Cultural History of Film in America. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-50979-2.

- Oldfield, Barney (Spring 1991). "'WINGS' A Movie and an Inspiration". Air Power History. 38 (1): 55–58. JSTOR 26272296. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- Orriss, Bruce W. (1986). When Hollywood Ruled the Skies. Aero Associates. ISBN 978-0-87910-056-8.

- Porter, Darwin (2005). Howard Hughes: Hell's Angel. Blood Moon Productions, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-9748118-1-9.

- Silke, James R. (June 2019). "Fists, Dames & Wings!" (PDF). Air Classics. Vol. 55, no. 6. ISSN 0002-2241. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2022.

- Suid, Lawrence H. (2002). Guts & Glory: The Making of the American Military Image in Film. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-9018-1.

- Stenn, David (2000). Clara Bow: Runnin' Wild. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8154-1025-6.

- Thompson, Frank T. (1983). William A. Wellman. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-1594-0.

- Thompson, Frank T. (2002). Texas Hollywood: Filmmaking in San Antonio since 1910. Maverick Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-893271-21-0.

- Gallagher, John Andrew; Thompson, Frank T. (2018). Nothing Sacred: The Cinema of William Wellman. Men With Wings Press. ISBN 978-0-9987699-2-9.

- Wellman, William A. Jr. (2006). The Man and His Wings: William A. Wellman and the Making of the First Best Picture. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-98541-7.

External links

[edit]- Wings at IMDb

- Wings at the TCM Movie Database

- Wings at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Wings essay by Dino Everett at National Film Registry

- Wings is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

- Wings at Virtual History

- Q&A With Paramount's VP of Archives on the restoration of Wings

- Wings at Rotten Tomatoes