| Battle of Lookout Mountain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Harper's weekly illustration of the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Military Division of the Mississippi:

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~12,000[2] | 8,726[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 671 total | 1,251 (including 1,064 captured or missing) | ||||||

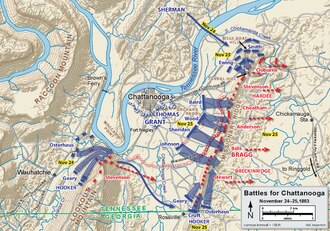

The Battle of Lookout Mountain also known as the Battle Above the Clouds was fought November 24, 1863, as part of the Chattanooga Campaign of the American Civil War. Union forces under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker assaulted Lookout Mountain, Chattanooga, Tennessee, and defeated Confederate forces commanded by Maj. Gen. Carter L. Stevenson. Lookout Mountain was one engagement in the Chattanooga battles between Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Military Division of the Mississippi and the Confederate Army of Tennessee, commanded by Gen. Braxton Bragg. It drove in the Confederate left flank and allowed Hooker's men to assist in the Battle of Missionary Ridge the following day, which routed Bragg's army, lifting the siege of Union forces in Chattanooga, and opening the gateway into the Deep South.

Background

[edit]Military situation

[edit]After their disastrous defeat at the Battle of Chickamauga, the 40,000 men of the Union Army of the Cumberland under Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans retreated to Chattanooga, Tennessee. Bragg's Army of Tennessee besieged the city, threatening to starve the Union forces into surrender. Bragg's troops established themselves on Missionary Ridge and Lookout Mountain, both of which had excellent views of the city, the Tennessee River flowing through the city, and the Union's supply lines. Lookout Mountain was actually a ridge or narrow plateau that extended 85 miles (137 km) southwest from the Tennessee River, culminating in a sharp point 1,800 feet (550 m) above the river. From the river the end of the mountain rose at a 45° angle and at about two thirds of the way to the summit it changed grade, forming a ledge, or "bench", 150–300 feet (50–90 m) wide, extending for several miles around both sides of the mountain. Above the bench, the grade steepened into a 500-foot (150 m) face of rock called the "palisades". Confederate artillery atop Lookout Mountain controlled access by the river, and Confederate cavalry launched raids on all supply wagons heading toward Chattanooga, which made it necessary for the Union to find another way to feed their men.[7]

The Union government, alarmed by the potential for defeat, sent reinforcements. On October 17, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant received command of the Western armies, designated the Military Division of the Mississippi. He moved to reinforce Chattanooga and replaced Rosecrans with Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas.[8]

Thomas launched a surprise amphibious landing at Brown's Ferry on October 27 that opened the Tennessee River by linking up Thomas's Army of the Cumberland with a relief column of 20,000 troops from the Eastern Theater's Army of the Potomac, led by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. Supplies and reinforcements were thus able to flow into Chattanooga over the "Cracker Line", greatly increasing the chances for Grant's forces. In response, Bragg ordered Lt. Gen. James Longstreet to force the Federals out of Lookout Valley, directly to the west of Lookout Mountain. The ensuing Battle of Wauhatchie (October 28–29) was one of the war's few battles fought exclusively at night. The Confederates were repulsed, and the Cracker Line was secured.[9]

On November 12, Bragg placed Maj. Gen. Carter L. Stevenson in overall command for the defense of the mountain, with Stevenson's own division positioned on the summit. The brigades of Brig. Gens. John K. Jackson, Edward C. Walthall, and John C. Moore were placed on the bench of the mountain. Jackson later wrote about the dissatisfaction of the commanders assigned to this area, "Indeed, it was agreed on all hands that the position was one extremely difficult to defense against a strong force of the enemy advancing under cover of a heavy fire."[10] Thomas L. Connelly, historian of the Army of Tennessee, wrote that despite the imposing appearance of Lookout Mountain, "the mountain's strength was a myth. ... It was impossible to hold [the bench, which] was commanded by Federal artillery at Moccasin Bend." Although Stevenson placed an artillery battery on the crest of the mountain, the guns could not be depressed enough to reach the bench, which was accessible from numerous trails on the west side of the mountain.[11]

Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman arrived from Vicksburg, Mississippi, with his 20,000 men of the Army of the Tennessee in mid-November. Grant, Sherman, and Thomas planned a double envelopment of Bragg's force, with the main attack by Sherman against the northern end of Missionary Ridge, supported by Thomas in the center and by Hooker, who would capture Lookout Mountain and then move across the Chattanooga Valley to Rossville, Georgia, and cut off the Confederate retreat route to the south. Grant subsequently withdrew his support for a major attack by Hooker on Lookout Mountain, intending the mass of his attack to be by Sherman.[12]

On November 23, Sherman's force was ready to cross the Tennessee River. Grant ordered Thomas to advance halfway to Missionary Ridge on a reconnaissance in force to determine the strength of the Confederate line, hoping to ensure that Bragg would not withdraw his forces and move in the direction of Knoxville, Tennessee, where Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside was being threatened by a Confederate force under Longstreet. Thomas sent over 14,000 men toward a minor hill named Orchard Knob and overran the Confederate defenders.[13]

Surprised by Thomas's move against Orchard Knob on November 23, and realizing that his center might be more vulnerable than he had thought, Bragg quickly readjusted his strategy. He recalled all units within a day's march that he had recently ordered to Knoxville. He began to reduce the strength on his left by withdrawing Maj. Gen. William H.T. Walker's division from the base of Lookout Mountain and placing them on the far right of Missionary Ridge. He assigned Hardee to command his now critical right flank, turning over the left flank to Carter Stevenson. Stevenson needed to fill the gap left by Walker's division from the mountain to Chattanooga Creek, so he sent Jackson's brigade of Cheatham's Division and Cummings' brigade of his own division into that position. (Jackson himself continued as temporary division commander on the mountain.) Stevenson deployed Walthall's brigade of 1,500 Mississippians as pickets near the base of the mountain, withholding enough for a reserve for Moore's brigade, which would defend the main line on the bench near the Cravens house.[14]

The Union side also changed plans. Sherman had three divisions ready to cross the Tennessee, but the pontoon bridge at Brown's Ferry had torn apart and Brig. Gen. Peter J. Osterhaus's division was stranded in Lookout Valley. After receiving assurances from Sherman that he could proceed with three divisions, Grant decided to revive the previously rejected plan for an attack on Lookout Mountain and reassigned Osterhaus to Hooker's command.[15]

Opposing forces

[edit]Union

[edit]| Key Union commanders at Lookout Mountain |

|---|

|

Grant's Military Division of the Mississippi assembled the following forces at Chattanooga:[16]

- The Army of the Cumberland, commanded by Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas.

- The Army of the Tennessee, commanded by Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman.

- The command of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, consisting of the XI Corps under Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard and the 2nd Division of the XII Corps under Brig. Gen. John W. Geary.

Hooker commanded the 10,000-man Union force engaged at the Battle of Lookout Mountain, which included three divisions, one from each of the Union armies, commanded by:

- Brig. Gen. John W. Geary from the XII Corps, Army of the Potomac. The brigade commanders were Cols. Charles Candy, George A. Cobham, and David Ireland (replacing Brig. Gen. George S. Greene, wounded at Wauhatchie).

- Brig. Gen. Charles Cruft from the IV Corps, Army of the Cumberland. The brigade commanders were Brig. Gen. Walter C. Whitaker and Col. William Grose.

- Brig. Gen. Peter J. Osterhaus from the XV corps, Army of the Tennessee. The brigade commanders were Brig. Gen. Charles R. Woods and Col. James A. Williamson.

Confederate

[edit]| Key Confederate commanders |

|---|

|

Bragg's Army of Tennessee had the following forces available in Chattanooga:[17]

- Hardee's Corps, under Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee, consisting of the divisions under Brig. Gen. John K. Jackson (Cheatham's Division), Brig. Gen. J. Patton Anderson (Hindman's Division), Brig. Gen. States Rights Gist (Walker's Division), and Maj. Gen. Simon B. Buckner (detached November 22 to Knoxville).

- Breckinridge's Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge, consisting of the divisions of Maj. Gens. Patrick R. Cleburne, Alexander P. Stewart, Carter L. Stevenson, and Brig. Gen. William B. Bate (Breckinridge's Division).

The 8,726 Confederate defenders at the Battle of Lookout Mountain were commanded by Maj. Gen. Carter L. Stevenson. Stevenson had two brigades from his own division of Breckinridge's Corps, as well as Brig. Gen. John K. Jackson, temporarily commanding Cheatham's division of Hardee's Corps, with two of his brigades:

- Brig. Gen. Edward C. Walthall (Cheatham's Division)

- Brig. Gen. John C. Moore (Cheatham's Division)

- Brig. Gen. John C. Brown (Stevenson's Division)

- Brig. Gen. Edmund Pettus (Stevenson's Division)

Battle

[edit]

On November 24, Hooker had about 10,000 men[2] in three divisions to operate against Lookout Mountain. Acknowledging that this was too large a force for a simple diversion, "Grant finally acceded to Thomas's persistent demand that a more serious effort be made." Hooker was ordered to "take the point only if his demonstration should develop its practicability."[18] Hooker ignored this subtlety and at 3 a.m. on November 24 ordered Geary "to cross Lookout Creek and to assault Lookout Mountain, marching down the valley and sweeping every rebel from it."[19]

Hooker did not plan to attack Stevenson's Division on the top of the mountain, assuming that capturing the bench would make Stevenson's position untenable. His force would approach the bench from two directions: Whitaker's brigade would link up with Geary at Wauhatchie, while Grose's brigade and Osterhaus's division would cross Lookout Creek to the southeast. Both forces would meet near the Cravens house. Osterhaus's division was in support: Woods's brigade was assigned to cover Grose and cross the creek after him; Williamson's brigade was assigned to protect Hooker's artillery near the mouth of Lookout Creek.[20]

Hooker arranged an impressive array of artillery to scatter the Confederate pickets and cover his advance. He had nine batteries set up near the mouth of Lookout Creek, two batteries from the Army of the Cumberland on Moccasin Point, and two additional batteries near Chattanooga Creek.[21]

Geary's expected dawn crossing of Lookout Creek was delayed by high water until 8:30 a.m. First to cross the footbridge was Cobham's brigade, followed by Ireland's, which formed to Cobham's left and became the center of Geary's battle line. Candy's brigade then extended the Union left down to the base of the mountain. Whitaker's brigade followed in the rear. From 9:30 to 10:30 a.m, Geary's skirmishers advanced through the fog and mist that obscured the mountain. Contact was made with Walthall's pickets 1 mile southwest of Lookout Point. The Confederates were significantly outnumbered and could not resist the pressure, falling back but leaving a number behind to surrender. Hooker ordered an artillery bombardment to saturate the Confederate line of retreat, but the effect was minimized because of poor visibility and the fact that the two forces were almost on top of each other.[22]

Much of the ground over which we advanced was rough beyond conception. It was covered with an untouched forest growth, seamed with the deep ravines, and obstructed with rocks of all sizes which had fallen from the frowning wall on our right. The ground passed over by our left was not quite so rough; but, taking the entire stretch of the mountain side traversed by our force ... it was undoubtedly the roughest battle field of the war.

The Union pursuit of the skirmishers was halted around 11:30 a.m. 300 yards southwest the point when Ireland and Cobham encountered Walthall's reserve southwest of the Cravens house. The two Confederate regiments repulsed Ireland's first attempt at assaulting their fieldworks. A second assault succeeded, enveloping and outnumbering the Confederates 4 to 1. Despite Walthall's attempt to rally his men, he could not prevent a disorderly retreat back toward the Cravens house. The Union brigades kept up their pursuit past the point and along the bench.[24]

As Geary's men appeared below the point around noon, Candy's brigade advanced across the lower elevations of the mountain, clearing the enemy from the east bank of Lookout Creek. Hooker ordered Woods's and Grose's brigades to begin crossing the foot bridge over the creek. Woods moved east at the base of the mountain, Grose moved up the slope. These movements isolated part of Walthall's Brigade and the entire 34th Mississippi was forced to surrender, along with 200 men from Moore's picket line.[25]

Moore was reluctant to take action. At 9:30 he had sent a message to Jackson asking where he should deploy his brigade and Jackson's reply at 11 a.m. expressed his frustration that Moore had seemingly forgotten the plan to defend the line at the Cravens house.[26] Peter Cozzens criticized Jackson's poor performance in leading the defense:

There was bungling aplenty among the Confederate commanders on Lookout Mountain that day, but no one displayed greater negligence than did Jackson. He remained glued to his headquarters ... near the base of the cliff. He was nearly a mile from the line he had been charged to defend. In his report of the battle, Jackson tried to excuse his dereliction of duty by arguing that his headquarters was a good spot from which to receive both commands from Stevenson on the summit and reports from the front line. That may have been true, but his presence was badly needed nearer the Cravens house. Jackson lacked even the presence of mind to call for reinforcements; Stevenson had to offer them.[27]

When Stevenson heard the fighting between Walthall and Geary, he ordered Pettus to take three regiments from the summit to assist Jackson. By this time, Moore's Alabamians were moving up amidst Walthall's retreating men, and they fired on Ireland's New Yorkers from 100 yards. Unable to see the size of the force resisting it through the fog, the Union men retreated beyond a stone wall. Moore's 1,000 men took positions in the rifle pits facing the wall and waited for the inevitable counterattack. Ireland's men were too exhausted to make an immediate move. As Whitaker's brigade arrived after 1 p.m., they stepped over Ireland's men and rushed into the attack. Candy's brigade was moving up the mountain side on Whitaker's left, followed by the brigades of Woods and Grose. Moore could see that he was being significantly outflanked on the right and chose to fall back rather than be surrounded.[28]

All of the Union brigades, including Ireland's tired men, began the pursuit. Hooker was concerned that his lines were becoming intermingled and confused by the fog and the rugged ground and they were tempting defeat if the Confederates brought up reinforcements in the right place. He ordered Geary to halt for the day, but Geary was too far behind his troops to stop them. Hooker wrote, "Fired by success, with a flying, panic-stricken enemy before them, they pressed impetuously forward."[29]

Moore's brigade was able to escape in the fog and Walthall had adequate time to form a rough defensive line 3–400 yards south of the Cravens house. His 600 men took cover behind boulders and fallen trees and made enough of a racket to dissuade Whitaker's men from moving against them. By this time Pettus's brigade of three Alabama regiments had descended from the summit and came to Walthall's assistance after 2 p.m.[30]

Hooker sent to Grant alternating messages of panic and bluster. At 1:25 p.m., he wrote that the "conduct of all the troops has been brilliant, and the success has far exceeded my expectations. Our loss has not been severe, and of prisoners I should judge that we had not less than 2,000." At around 3 p.m., he wrote "Can hold the line I am now on; can't advance. Some of my troops out of ammunition; can't replenish." Responding to a plaintive message sent from Whitaker, General Thomas approved the transfer of Brig. Gen. William P. Carlin's brigade (XIV Corps) to aid Hooker. (Carlin was delayed for hours attempting to cross the river and reported to Geary at 7 p.m., playing no role in the combat.) But by sunset, a confident Hooker informed Grant that he intended to move into Chattanooga Valley as soon as the fog lifted. He signaled "In all probability the enemy will evacuate tonight. His line of retreat is seriously threatened by my troops."[31]

Bragg responded to a request by Stevenson for reinforcements by sending Col. J.T. Holtzclaw's brigade under the condition that it be used only to cover a Confederate withdrawal from Lookout Mountain, ordering Stevenson at 2:30 p.m. to withdraw to the east side of Chattanooga Creek. Stevenson was reluctant to break contact until his troops on the summit could escape on the Summertown Road into the Chattanooga Valley. The brigades of Walthall, Pettus, and Moore were ordered to hold on for the rest of the afternoon. For hours through the afternoon and into the night, the six Alabama regiments under Pettus and Moore fought sporadically with the Union troops through dense fog, neither side able to see more than a few dozen yards ahead nor make any progress in either direction.[32]

Aftermath

[edit]I have been the instrument of Almighty God. ... I stormed what was considered the ... inaccessible heights of Lookout Mountain. I captured it. ... This feat will be celebrated until time shall be no more.

By midnight, Lookout Mountain was quiet. Pettus and Holtzclaw received orders at 2 a.m. to march off the mountain. Postwar writings of both Union and Confederate veterans refer to a brilliant moon, which slipped into the blackness of a total lunar eclipse, screening the Confederate withdrawal.[34] That night Bragg, stunned by the defeat on Lookout Mountain, asked his two corps commanders whether to retreat from Chattanooga or to stand and fight. Hardee counseled retreat, but Breckinridge convinced Bragg to fight it out on the strong position of Missionary Ridge.[35] Accordingly, the troops withdrawn from Lookout Mountain were ordered to the left flank of Bragg's army.[36]

On November 25, Hooker's men encountered difficulty rebuilding the burned bridges over Chattanooga Creek and were delayed in their movement toward the left flank of Bragg's remaining forces on Missionary Ridge. They reached the Rossville Gap as Thomas's men were sweeping over Missionary Ridge. Hooker faced his three divisions to the north and drove into Bragg's flank, furthering the disruption of the Confederate line, sending the Army of Tennessee into full retreat. Hooker continued his role in the campaign with his unsuccessful pursuit of the Confederates that was beaten back at the Battle of Ringgold Gap.[37]

Casualties for the Battle of Lookout Mountain were relatively light by the standards of the Civil War: 671 Union, 1,251 Confederate (including 1,064 captured or missing).[6] Sylvanus Cadwallader, a war reporter accompanying Grant's army, wrote that it was more like a "magnificent skirmish", than a major battle.[38] General Grant, whose focus was on the northern end of Missionary Ridge—and who was usually partial to the achievements of his key subordinates in the Western armies—later denigrated Hooker's achievement, writing in his memoirs, "The battle of Lookout Mountain is one of the romances of the war. There was no such battle and no action even worthy to be called the battle on Lookout Mountain. It is all poetry."[39] Nevertheless, the action was important in assuring control of the Tennessee River and the railroad into Chattanooga and endangering the entire Confederate line on Missionary Ridge. Brig. Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs, quartermaster general of the Union Army, observing the fog-shrouded action from Orchard Knob, was the first writer to name it the "Battle Above the Clouds".[40]

Portions of the Lookout Mountain battlefield are preserved by the National Park Service as part of the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park.

See also

[edit]- Troop engagements of the American Civil War, 1863

- List of costliest American Civil War land battles

- Armies in the American Civil War

- Tennessee Highway Marker. "Battle of Lookout Mountain, Tennessee, American Revolution". Retrieved March 24, 2019.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Only the Second Division.

- ^ a b McDonough, p. 130; Cleaves, p. 196; Korn, p. 130.

- ^ Hallock, p. 131; Korn, p. 131, cites 7,000.

- ^ Return of casualties in the Union forces (XI and XII Corps): Official Records, Series I, Volume XXXI, Part 2, page 83

- ^ See also Union casualties in Battle of Missionary Ridge.

- ^ a b Korn, p. 136; Taylor, Samuel, North Georgia History, cites 710 Union, 521 Confederate; Hebert, p. 265, cites 362 Union, 1,250 Confederate.

- ^ Cozzens, pp. 15-16.

- ^ Woodworth, Six Armies, pp. 148-49.

- ^ Woodworth, Six Armies, pp. 159–67; Korn, pp. 89-95; McDonough, pp. 76-94; Eicher, pp. 602-04.

- ^ Cozzens, p. 117.

- ^ Connelly, p. 270; McDonough, pp. 134-35.

- ^ Woodworth, Six Armies, p. 172; McDonough, pp. 108-09.

- ^ Korn, pp. 120–21; Woodworth, Six Armies, pp. 180–81; McDonough, pp. 110–16; Hebert, p. 263; Eicher, pp. 605-06.

- ^ McDonough, pp. 124, 126; Cozzens, pp. 139–42; Hallock, p. 131; Esposito, text to map 116.

- ^ McDonough, pp. 129–30; Cozzens, pp. 143–44; Woodworth, Nothing but Victory, p. 465.

- ^ Eicher, pp. 601-02.

- ^ Cozzens, pp. 408-15.

- ^ Cozzens, p. 144.

- ^ Cozzens, p. 160; Woodworth, Six Armies, pp. 185–86; McDonough, pp. 130-37.

- ^ Cozzens, pp. 159-160.

- ^ McDonough, p. 133; Cozzens, pp. 162-63.

- ^ Cozzens, pp. 165–74; McDonough, pp. 131-35.

- ^ Cozzens, p. 168.

- ^ Cozzens, pp. 174–78; McDonough, p. 133.

- ^ Cozzens, pp. 179-80.

- ^ Cozzens, p. 180.

- ^ Cozzens, p. 181.

- ^ Cozzens, pp. 181-86.

- ^ Cozzens, p. 187.

- ^ Korn, p. 133; McDonough, pp. 137–39; Cozzens, pp. 188–90; Eicher, p. 607.

- ^ Cozzens, pp. 190-91.

- ^ Cozzens, pp. 192–97; Hallock, pp. 132-34.

- ^ McDonough, p. 142.

- ^ Cozzens, p. 197; Sword, p. 227; NASA Five Millennium Catalog of Lunar Eclipses

- ^ Cozzens, p. 196; Hallock, p. 136; McDonough, p. 140.

- ^ Woodworth, Six Armies, pp. 190–91; Eicher, p. 609.

- ^ Eicher, 610; Hebert, 266; McDonough, 211-12;Woodworth, Nothing but Victory, p. 478; Cozzens, pp. 244–45, 313–19, 370–84; McDonough, pp. 211–12, 220-25.

- ^ Korn, p. 136.

- ^ McDonough, p. 142; Korn, p. 136.

- ^ Hebert, p. 265; McDonough, p. 129.

- ^ Walker, The Soldier Artist, NPS Civil War Series

References

[edit]- Cleaves, Freeman. Rock of Chickamauga : The Life of General George H. Thomas. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1974. ISBN 0-8371-6973-9.

- Connelly, Thomas L. Autumn of Glory: The Army of Tennessee 1862–1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971. ISBN 0-8071-2738-8.

- Cozzens, Peter. The Shipwreck of Their Hopes: The Battles for Chattanooga. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994. ISBN 0-252-01922-9.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959. OCLC 5890637. The collection of maps (without explanatory text) is available online at the West Point website.

- Hallock, Judith Lee. Braxton Bragg and Confederate Defeat. Vol. 2. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1991. ISBN 0-8173-0543-2.

- Hebert, Walter H. Fighting Joe Hooker. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8032-7323-1.

- Korn, Jerry, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. The Fight for Chattanooga: Chickamauga to Missionary Ridge. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. ISBN 0-8094-4816-5.

- McDonough, James Lee. Chattanooga—A Death Grip on the Confederacy. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1984. ISBN 0-87049-425-2.

- Woodworth, Steven E. Nothing but Victory: The Army of the Tennessee, 1861–1865. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. ISBN 0-375-41218-2.

- Woodworth, Steven E. Six Armies in Tennessee: The Chickamauga and Chattanooga Campaigns. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8032-9813-7.

- National Park Service battle description

- CWSAC Report Update

Further reading

[edit]- Horn, Stanley F. The Army of Tennessee: A Military History. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1941. OCLC 2153322.

- Sword, Wiley. Mountains Touched with Fire: Chattanooga Besieged, 1863. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1995. ISBN 0-312-15593-X.

- Powell, David A. Battle Above the Clouds: Lifting the Siege of Chattanooga and the Battle of Lookout Mountain, October 16–November 24, 1863. Emerging Civil War Series. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2017. ISBN 978-1-61121-377-5.

- The Meriwether Family Papers, W.S. Hoole Special Collections Library, The University of Alabama.

External links

[edit]- Chattanooga Campaign: Maps (Battle of Lookout Mountain), histories, photos, and preservation news (Civil War Trust)

- Eyewitness accounts by Sergeant Luther Mesnard of Company D of 55th Ohio

- Photographs from Lookout Mountain battlefield Archived 2017-08-13 at the Wayback Machine