| Direct factor Xa inhibitor | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Synonyms | Direct Xa inhibitor, novel oral anticoagulant |

| Use | Treat and prevent venous thromboembolism |

| Mechanism of action | Inhibit fibrin formation in the final common pathway of the coagulation cascade |

| Chemical class | Direct factor Xa inhibitors[1] |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Direct factor Xa inhibitors (xabans) are anticoagulants (blood thinning drugs), used to both treat and prevent blood clots in veins, and prevent stroke and embolism in people with atrial fibrillation (AF).[2][3]

Medical use

[edit]Direct factor Xa inhibitors include rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban, and are types of direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC), which are blood thinning drugs, one of the classes of antithrombotic drugs.[4][5][6] They are commonly prescribed to treat and prevent blood clots in veins, prevent stroke and embolism in people with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF) who have other risk factors, and prevent blood clots after routine knee and hip replacement surgery.[2][3][7]

Direct factor Xa inhibitors can be considered as an alternative to warfarin, particularly if a person is on several other medications that interact with warfarin, or if attending medical appointments and laboratory monitoring becomes difficult.[8] Factors considered before deciding on whether warfarin or a DOAC or which direct factor Xa inhibitor is used, include: the presence or absence of valvular heart disease, state of kidney function, the risk of stroke and the risk of bleeding.[8]

Contraindications

[edit]Direct Xa inhibitors are contraindicated in people who are actively bleeding or who are at high risk of bleeding. The effects on a fetus or neonate are unknown, hence these drugs are not prescribed in pregnancy or breast feeding mothers.[2]

Adverse effects

[edit]Side effects may include bleeding, most commonly from the nose, gastrointestinal tract (GI) or genitourinary system.[2] Compared to the risk of bleeding with warfarin use, direct factor Xa inhibitors have a higher risk of GI bleeding, but lower risk of bleeding in the brain.[2] Other side effects may include stomach upset, dizziness, anemia or increased blood levels of liver enzymes.[2]

Overdose

[edit]A specialist may request a quantitative factor Xa assay in a situation of overdose.[2] Andexanet alfa, a specific antidote to reverse the anticoagulant activity of direct Xa inhibitors in the event of major bleeding, was approved by the FDA in 2018.[9] It is also available in the UK.[10]

Drug interactions

[edit]The risk of bleeding is increased if used at the same time as other blood thinning drugs such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet drugs and heparin.[2] The blood thinning effects can be reduced if used at the same time as rifampicin and phenytoin, and increased with fluconazole.[2][11] Compared to warfarin they have fewer interactions with other medications.[8]

Pharmacology

[edit]Mechanism of action

[edit]

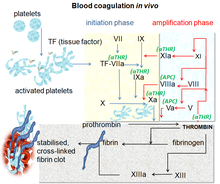

Direct factor Xa inhibitors block the enzyme called factor Xa, preventing the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin in the final common pathway of clot formation in veins and the heart.[2]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]They have a rapid onset and offset of action. This means it is often possible to pause them 12 to 48 hours before surgery and resume them shortly after the surgery. By contrast, warfarin and phenprocoumon are often paused up to a week before surgery, and low-molecular-weight heparins are used to "bridge" the therapy gap, typically for several weeks.[12][13]

Also in contrast to warfarin and phenprocoumon, direct factor Xa inhibitors do not require frequent monitoring of the prothrombin time (also called the INR) and dose adjustments.[12]

History

[edit]

Prior to the introduction of direct factor Xa inhibitors, vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin were the only oral anticoagulants for over 60 years, and together with heparin have been the main blood thinners in use. People admitted to hospital requiring blood thinning were started on an infusion of heparin infusion, which thinned blood immediately, and were then discharged from the hospital after almost a week on warfarin, which takes time to work. The ability to have a shorter stay in hospital came with the advent of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and the ability of self-injecting subcutaneously at home. Biotechnology developments then paved way for the first successful synthetic anticoagulants including hirudin.[6] The monitoring of warfarin and keeping the international normalized ratio (INR) between 2.0 and 3.0, along with avoiding over and under treatment, has driven a search for an alternative.[3][14]

A naturally occurring inhibitor of factor Xa was reported in 1971 by Spellman et al. from the dog hookworm.[15] In 1987, Tuszynski et al. discovered antistasin, which was isolated from the extracts of the Mexican leech, Haementeria officinalis.[16][17] Later, another naturally occurring inhibitor, tick anticoagulant peptide (TAP) was isolated from the extract of tick Ornithodoros moubata.[18] Trials subsequently demonstrated efficacy and safety against warfarin for stroke prevention in AF and against LMWH for treatment and prevention of VTE including in people undergoing hip or knee replacement.[19]

Society and culture

[edit]Economics

[edit]The cost of direct Xa inhibitors can reach more than 50 times that of warfarin, although this difference may be offset by lower monitoring costs.[2][5]

Brand names

[edit]Brands include rivaroxaban (brand name Xarelto) from Bayer, apixaban (Eliquis) from Bristol-Myers Squibb,[3] edoxaban (Lixiana) from Daiichi,[20] and betrixaban (Bevyxxa) from Portola Pharmaceuticals.[21]

Discontinued xabans

[edit]Xabans that never reached the market include darexaban (YM150) from Astellas,[22][23] otamixaban from Sanofi,[24] letaxaban (TAK-442) from Takeda,[25] and eribaxaban (PD0348292) from Pfizer.[26]

References

[edit]- ^ "WHOCC – ATC/DDD Index". whocc.no. Archived from the original on 4 April 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hitchings, Andrew; Lonsdale, Dagan; Burrage, Daniel; Baker, Emma (2019). The Top 100 Drugs: Clinical Pharmacology and Practical Prescribing (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-0-7020-7442-4.

- ^ a b c d Mary Lou Turgeon (29 June 2020). Clinical Hematology: Theory & Procedures, Enhanced Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 575–577. ISBN 978-1-284-29449-1.

- ^ "List of Factor Xa inhibitors". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 4 April 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ a b BNF (80 ed.). London: BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. pp. 133–139. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

- ^ a b American Society of Hematology (2008). "Antithrombotic Therapy - Hematology.org". hematology.org. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Chen, Ashley; Stecker, Eric; Warden, Bruce A. (7 July 2020). "Direct Oral Anticoagulant Use: A Practical Guide to Common Clinical Challenges". Journal of the American Heart Association. 9 (13): e017559. doi:10.1161/JAHA.120.017559. PMC 7670541. PMID 32538234.

- ^ a b c Kiser, Kathryn (2017). Oral Anticoagulation Therapy: Cases and Clinical Correlation. Springer. p. 11. ISBN 9783319546438.

- ^ Portola Pharmaceuticals, Inc. "U.S. FDA Approves Portola Pharmaceuticals' Andexxa, First and Only Antidote for the Reversal of Factor Xa Inhibitors". GlobeNewswire News Room. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ BNF (80 ed.). London: BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

- ^ Vranckx, Pascal; Valgimigli, Marco; Heidbuchel, Hein (7 March 2018). "The Significance of Drug—Drug and Drug—Food Interactions of Oral Anticoagulation". Arrhythmia & Electrophysiology Review. 7 (1): 55–61. doi:10.15420/aer.2017.50.1. ISSN 2050-3369. PMC 5889806. PMID 29636974.

- ^ a b Haberfeld H, ed. (2020). Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. Xarelto 20 mg Filmtabletten; Eliquis 5 mg Filmtabletten; Lixiana 60 mg Filmtabletten.

- ^ Douketis, J. D.; Healey, J. S.; Brueckmann, M.; Eikelboom, J. W.; Ezekowitz, M. D.; Fraessdorf, M.; Noack, H.; Oldgren, J.; Reilly, P.; Spyropoulos, A. C.; Wallentin, L.; Connolly, S. J. (2015). "Perioperative bridging anticoagulation during dabigatran or warfarin interruption among patients who had an elective surgery or procedure. Substudy of the RE-LY trial". Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 113 (3): 625–32. doi:10.1160/TH14-04-0305. PMID 25472710.

- ^ Franchini, Massimo; Liumbruno, Giancarlo M.; Bonfanti, Carlo; Lippi, Giuseppe (March 2016). "The evolution of anticoagulant therapy". Blood Transfusion. 14 (2): 175–184. doi:10.2450/2015.0096-15. ISSN 1723-2007. PMC 4781787. PMID 26710352.

- ^ Spellman, GG Jr.; Nossel, HL (1971). "Anticoagulant activity of dog hookworm". Am J Physiol. 222 (4): 922–27. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1971.220.4.922. PMID 5102508.

- ^ Holt, G. D.; Krivan, H. C.; Gasic, G. J.; Ginsburg, V. (1989). "Antistasin, an inhibitor of coagulation and metastasis, binds to sulfatide (Gal(3-SO4) beta 1-1Cer) and has a sequence homology with other proteins that bind sulfated glycoconjugates". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 264 (21): 12138–40. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)63831-1. PMID 2745433.

- ^ "P15358 antistasin". Uniprot. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ Mousa, Shaker A. (2004). Anticoagulants, Antiplatelets, and Thrombolytics. Humana Press. pp. 96–99. ISBN 978-1-59259-658-4.

- ^ Bauer, K. A. (6 December 2013). "Pros and cons of new oral anticoagulants". Hematology. 2013 (1): 464–70. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2013.1.464. PMID 24319220.

- ^ Turpie, AG (January 2008). "New oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation". European Heart Journal. 29 (2): 155–65. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm575. PMID 18096568.

- ^ Eriksson BI, Quinlan DJ, Weitz JI (2009). "Comparative pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of oral direct thrombin and factor xa inhibitors in development". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 48 (1): 1–22. doi:10.2165/0003088-200948010-00001. PMID 19071881. S2CID 35948814.

- ^ Grogan, Kevin (29 September 2011). "Astellas pulls the plug on darexaban". Pharmatimes. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ "Astellas Pharma Inc. Discontinues Development of Darexaban (YM150),an Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibitor". Astellas Pharma. 28 September 2011.

- ^ "AstraZeneca, Sanofi Cut Programs". Chemical & Engineering News. 91 (23). American Chemical Society: 17. 10 June 2013.

Sanofi is ending development on two compounds, the anticancer compound iniparib and the anticoagulant otamixaban, both of which flunked Phase III studies.

- ^ Dwyer J, Walsh C (May 2013). "First Time European Approval for Xarelto in ACS". Decision Resources. Archived from the original on 19 July 2014.

- ^ "Eribaxaban". AdisInsight. 14 March 2021.